Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

– Live Blood Analysis Connected to a Camera

LIVE BLOOD ANALYSIS NATURAL therapies You stare in awe at the blood cells floating lazily across the screen in front of you. The background looks like the Milky Way, A window into occasionally studded with sparkling ‘moon rocks’. The eeriness of the scene belies the truths to be revealed about your health. This is live blood analysis. This article has been co-authored with Dr Okker Botha our inner world Live blood analysis, also known as HEALTH AND LIFESTYLE nutritional microscopy or dark-field Live blood analysis is especially useful in microscopy, is fundamentally the analysis of preventive health care. The red blood cells living blood under a powerful microscope, carry oxygen and the plasma carries nutrients – live blood analysis connected to a camera. to every cell in the body. The state of health or ill-health of the blood therefore affects every The condition and quality of our red blood cell in the body, so it is clear that by improving cells has a direct impact on our present and the health of the blood, one can improve the future health, with signs of stress and disease health of the body. appearing in the blood years before they manifest as symptoms in the body. Researchers all over the world have examined and studied live capillary blood for many years. THE BIOLOGICAL TERRAIN Although many different approaches have Live blood testing enables one to see exactly been used and many opinions expressed, a how one’s blood behaves in the body, giving central truth has emerged: the human body a clear picture of health at a cellular level. -

Complementary Medicine the Evidence So

Complementary Medicine The Evidence So Far A documentation of our clinically relevant research 1993 - 2010 (Last updated: January 2011) Complementary Medicine Peninsula Medical School Universities of Exeter & Plymouth 25 Victoria Park Road Exeter EX2 4NT Websites: http://sites.pcmd.ac.uk/compmed/ http://www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/fact E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 1392 424989 Fax: +44 (0) 1392 427562 2 PC2/Report/DeptBrochure/Evidence17 14/02/2011 3 Contents 1 Introduction................................................................................................................11 1.1 Background and history of Complementary Medicine...............................................................11 1.2 Aims.................................................................................................................................................11 1.3 Research topics................................................................................................................................11 1.4 Research tools..................................................................................................................................11 1.5 Background on the possibility of closure in May 2011..............................................................12 2 The use of complementary medicine (CM)..............................................................13 2.1 General populations........................................................................................................................13 -

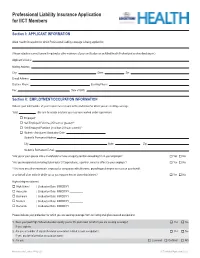

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members Section I: APPLICANT INFORMATION Allied Health Occupation for which Professional Liability coverage is being applied for: (Please attach a current license if required or other evidence of your certification as anAllied Health Professional as described above.) Applicant’s Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: E-mail Address: Daytime Phone: Evening Phone: Fax: Date of Birth: Section II: EMPLOYMENT/OCCUPATION INFORMATION Indicate your total number of years experience relevant to the profession for which you are seeking coverage. Total: (Be sure to include any time you may have worked under supervision) o Employed* o Self-Employed Full-time (25 hours or greater)** o Self-Employed Part-time (less than 25 hours a week)** o Student - Anticipated Graduation Date: Student’s Permanent Address: City: State: Zip: Student’s Permanent E-mail: *Are you or your spouse also a shareholder or have an equity position exceeding 5% in your employer? o Yes o No *Are you incorporated (including Sub chapter S Corporations), a partner, owner or officer to your employer? o Yes o No **Are there any other individuals, employed or associated with otherwise, providing professional services on your behalf, or on behalf of an entity in which you or your spouse has an ownership interest? o Yes o No Highest degree obtained: o High School | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Associate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Bachelors | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Masters | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Doctorate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ Please indicate your profession for which you are seeking coverage from our listing of eligible covered occupations: ______________________________________ 1. -

Live Blood Analysis: Science Or Quackery?

Live Blood Analysis: Science or Quackery? by Dr O. R. Botha from Neogenesis Systems We receive enquiries from time to time about the scientific basis of live blood analysis. Many people are concerned by the many sites on the internet claiming that live blood analysis is pseudoscience and nothing more than a gimmick used by quacks to sell you something. It is criticised for not being scientifically tested like other medical tests and the conclusion is made that therefore it can not have any real value as an investigative tool. The internet is a platform through which people can express their views and opinions freely. One can find numerous websites dedicated to exposing quackery and pseudoscience that apply these labels to homeopathy, herbalism, detoxification treatments, iridology and essentially anything that doesn’t involve drugs or surgery. Many of these articles are written by people who have no medical training and who are completely ignorant about the modality they are condemning. I recently came across such a website where the author claimed that a live blood sample will have red cell aggregation in one area and appear normal in other areas, simply because of how the sample is prepared. He then proceeded to explain how a peripheral blood smear is prepared with two slides. Had the author taken the time to look into live blood analysis in more detail, he would have discovered that live blood specimens are not at all prepared like peripheral blood smears. In a live blood specimen a single drop of blood is placed on a small cover slip, which is then placed on the slide, allowing the blood to spread evenly. -

BIOLOGICAL TERRAIN Looking at The

main feature: BIOLOGICAL TERRAIN looking at the 36-year-old female, vegetarian for 25 years, presented with a two-year history of polyarthritis in her wrists (distal radio- A ulnar joint, os pisiformis, os scaphoideum) and ankles that bore all the hallmarks of inflammation related to an auto- immune disorder: symmetrical tumor, dolor, calor, patient rubor and functio laese. Over a period of two years she consulted three consultant rheumatologists; her drug regime In his follow-up to last month’s article on Biological Terrain initially started with Ibuprofen and Naproxen, this Analysis, chartered physiotherapist, acupuncturist and was later changed to Arthrotec 50, to which was added Amitriptyline 20mg nocte and naturopath Han van de Braak, BSc, LicAc, MCSP, Hydroxychloroquine 400mg daily. It could not be MBAcC, shows the practical relevance of these these decided whether she suffered from non-specific techniques by following a patient through the process. arthralgia (connective tissue disease) or inflammatory joint disease. By March 2001 her diagnosis was confirmed as inflammatory polyarthritis with antiphospholipid syndrome; her drug regime had altered to one week's course of Prednisolone 20mg/day, Hydroxychloroquine 400mg and aspirin 75mg daily. Laboratory results (see below) had shown lupus anticoagulant and low positive anticardiolipin antibodies. With migraine-like headaches in her history she was considered to have antiphospholipid syndrome. Both her lupus serology and rheumatoid factor, however, remained negative. Further medication with Mepacrine or Azathioprine was to be considered. Scans Her MRI (Figure 1, opposite, is one single image) report of the left wrist noted the following: lobulated mass (2.3 x 1.2cm) deep to pisiform bone extending upwards into the distal carpal row (was a ganglion). -

Manton Chris Resume Dec 2012

Christopher Manton..B.App.Sci (biochem), Dip Ed., M Nut&dietetics., Ass. Dip.Nat. Mem CMA Nutritional Biochemist/ Naturopath ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 edmund st Queens Park NSW 2022 (Australia) mobile ph : 61-407 974 798 email : [email protected] web : www.healthdetective.com.au D.O.B 10.4.1961 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 1979-1983 University of Technology (UTS) - Gore Hill Sydney Bachelor of Applied Science with Credit Biochemistry Major 1984 Sydney Institute of Education - Sydney Post-Graduate Diploma In Education (Secondary Sci..) 1985-1986 Flinders University, Adelaide South Australia Post-Graduate Degree in Nutrition & Dietetics 1993-1994 Adelaide Biologics(Research &Testing Services) Live Blood Analysis-HLB-Blood Test Certificate 1994 College of Somatic Studies (Correspondence Training) Studies in Nutritional Therapy & Nutritional Medicine 1 CAREER OVERVIEW I am an experienced health analyst and nutritional medicine specialist with now 18 years of experience running a private practice-nutritional medicine health clinic in Sydney and Adelaide. In my clinic setting i am using darkfield blood analysis (live blood testing), the dry layer blood test (HLB-blood testing) and computer software analysis of blood chemistry profiles. Additionally, I utilize a range of other functional testing to determine cause of disease/ illness and sub-par health of my clients You can view some of the live blood photo’s i have accumulated over the years in my clinic and some brief descriptions conerning how your can view in live blood that are used in the health screening and educational process for clients. I have a strong background in the tertiary education of naturopathic students where I was involved in both a lecturing context and curriculum module development nutrition, nutritional medicine and nutritional biochemistry. -

Grace Baptist Church C Hurc H’S Activity Center

Looking for Lodging? Turn to Page 5B for B&Bs Salado VVillageillage VVoiceoice Vol. XXIX, Number 15 Thursday, July 20, 2006 254/947-5321 fax 254/947-9479 www.saladovillagevoice.com 50¢ Stadium renovations approved for Greenway to being work BY TIM FLEISCHER to retile one classroom in 29 new teachers. This is EDITOR-IN-CHIEF the high school. about a third of the overall The board also ap- workforce in the district. Salado I.S.D. Trust- proved the student code Dr. Battershell said that ees July 17 approved a of conduct, the vendor list the district has lost teach- bid of $232,358.41 plus and the appraisal calendar ers this year to retirement, a performance bond for for 2006-07. pregnancy and other renovations and expansion Trustees determined school districts that pay of Eagle Stadium. The that the following are more. district will enter into an acute shortage areas for In addition, she said interlocal agreement with teaching: high school that the current trend Greenway for the project, mathematics, high school across the state is that Paddlers and swimmers will want to avoid contact with Salado Creek water until the which is part of the bond science, Spanish and spe- more teachers are retiring causes of high E. coli counts can be determined and alleviated. (PHOTO BY MARILYN FLEISCHER) proposal approved by vot- cial education. than entering the work- ers this spring. Superintendent Robin force from colleges and The renovation project Battershell told the universities. will bring the stadium into board that this designa- Trustees then approved Without a paddle compliance for Americans tion would not have any the hire of the following with Disabilities Act benefits for the district at teachers: Jessica Chaney, High E. -

Alkalizing Nutritional Therapy in the Prevention and Reversal of Any Cancerous Condition

International Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine Alkalizing Nutritional Therapy in the Prevention and Reversal of any Cancerous Condition Abstract Opinion Due to the evident ineffectiveness of conventional cancer treatments (e.g. Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2015 chemotherapy and radiation), more efficient alternatives are needed. The potential of Alkaline Nutritional Infusion (ANI) as a legitimate alternative to chemotherapy and radiation is examined. While largely ignored in conventional 1Universal Medical Imaging Group, USA oncology, the pH of the interstitial fluids is suggested as paramount in identifying 2Medical doctor, non-invasive medical diagnostics, USA a cancerous condition. It is further suggested that cancer is an over-acidic condition of the body that can be reversed and prevented with alkalizing *Corresponding author: Robert O Young, pH Miracle Inc., treatments such as ANI. Full Body Bio-Electro Scan (FBBES) is presented as a 16390 Dia del Sol, Valley Center, California, 92082, USA, noninvasive means to examine body pH and the presence of cancer. In addition, Tel: 760 751 8321; Email: and non-invasive Full-Body Thermography (FBT) and Full-Body Ultrasound (FBU) are Universal Medical Imaging Group, 12410 Burbank Blvd, presented as a noninvasive means to examine the physiology and the anatomy of Valley Village, California, 91607, USA, Tel: 818 987 6886; the ograns, glands and tissues for inflammation, calcifications, cysts and tumors Email: in the prevention and treatment of any cancerous condition. Finally, Live Blood Analysis (LBA) and Dried Blood Analysis (DBA) are non-invasive hematology Received: August 29, 2015 | Published: November 24, 2015 tests for evaluating the health of the red and white blood cells and to view inflammatory and malignancy at the cellular level. -

Membership Application Form 2021

MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM 2021 CONTACT DETAILS Name: Date of birth: Tel: Cell: Email: Address: City: Region: ZIP Code: Short description of practice: AFFILIATIONS BHF no.: HPCSA no.: AHPCSA no.: Are you a member of SA Medical Association? QUALIFICATIONS Qualifications and Training: Institution: Year: PRACTICE MODALITIES – PLEASE INDICATE WITH X Acupuncture Herbalism Nutritional therapy Anthroposophic medicine Homotoxicology Orthomolecular medicine Anti-aging medicine Homeopathy Ozone therapy Ayurvedic medicine Hypnotherapy Prolotherapy Biopuncture Intravenous therapy PNI BEMER therapy Kinesiology Rife Resonator therapy Bio-energetic tools Laser therapy TCM Breathwork Lifestyle modification Trauma releasing exercise Chelation Live blood analysis VoiceBio Energy healing Mindfulness-based medicine Western medicine Functional medicine Naturopathy Other, please specify: MEMBERSHIP CATEGORIES 1. Medical members Medical doctors and biological dentists registered with HPCSA R990 p.a. 2. Allied members Allied Doctors registered with the AHPCSA R880 p.a. All other practitioners registered with a medical statutory council – dieticians, psychologists, nurses, pharmacists and vets, etc. – include registration number Clinical nutritionists – attach qualifications – must have 3 year 3. Associates BSc degree or diploma R880p.a. Ethnomedicine practitioners registered with EPASA. Other practitioners who have FM and IM qualifications – please include your qualifications for the EXCO to evaluate your application. This is a new category to accommodate everyone who does NOT fit into the above categories, but who does practise some aspect of IM. They will not participate in the SASIM Professional Discussion Group 4. Affiliates R770 p.a. (previously called the Medical chats) and will not be listed on the SASIM website. They may join regional Whatsapp groups, attend meetings as “members” and benefit from group discounts. -

The Main Interest in Life and Work Is to Become Someone Else That You Were Not in the Beginning

The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning. If you knew when you began a book what you would say at the end, do you think that you would have the courage to write it? The game is worthwhile insofar as we don’t know what will be the end. Michel Foucault, Technologies of the Self University of Alberta Candida and the Discursive Terms of Undefined Illness: Ghostly Matters, Leaky Bodies and the Dietary Taming of Uncertainty by Alissa Overend A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation Department of Sociology ©Alissa Overend Fall, 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Dr. Sharon Rosenberg, Sociology Dr. Debra Shogan, Physical Education and Recreation Dr. Cressida Heyes, Philosophy Dr. Amy Kaler, Sociology Dr. -

Discovery of the SALT of the EARTH by Alfons Ven New

Discovery of THE SALT OF THE EARTH By Alfons Ven New possibilities for the prevention of (life-threatening) diseases. The right support for regular treatment Alfons Ven develops the MSP ( Matrix Support Program ) or Immune MSP Here follows the unusual story of a search for new sources of becoming and staying healthy. On the one hand this is the personal story of the Belgian Alfons Ven, who ended up in a serious physical breakdown, was given up by his doctors and decided to look himself for a way out of it. At the same time it is also the story of a journey, a discovery of new remedies, new methods of preparation and of thousands of people who started using these new Ven-preparations. For many of them this meant a turning point in their lives. Alfons Ven’s successful search finds its temporary culmination in the discovery of a crucial element which he calls “ Salt of the Earth”. This “salt” is a vital component of his Immune Program. A program to improve and support the human immune system, an important support to prevent and reduce life- threatening diseases. Cancer researchers believe that the dysfunction of the immune system is the decisive factor that brings on this disease. Never before have methods been developed that directly revitalize a dysfunctional and disordered immune system. Therefore Ven’s Immune Program is a breakthrough. ‘ It is a program with enormous potential’ says Alfons Ven. The preparation offers many possibilities for the prevention of numerous diseases. In this booklet you will find first a short résumé of the development of the Immune Program, followed by a personal story of Alfons Ven himself, in which he tells of his quest and discoveries in an evocative way. -

I Beat Cancer!

I BEAT CANCER! I BEAT CANCER! VERSION 1.00 PHI NATURAL HEALTH INTERNATIONAL LTD Website: www.naturalcancertreatments.com Email: [email protected] Important Note: Do not delay in seeking advice from a qualified, licensed medical professional about treatment for your cancer. The information presented here is no way meant to discourage you from undertaking conventional treatments for your cancer, but hopefully will support you and your doctor to undertake 'smarter', more effective approaches to beat your cancer. The information is provided for educational and informational purposes only, and is not intended to be a substitute for the diagnosis, treatment and advice of a qualified, licensed medical professional. The information is provided to support your informed consent to any treatment program you may decide to undertake. Self-treatment for clinical cancer is not advised. Statements regarding alternative treatments for cancer have not been evaluated by the FDA. Please consult your qualified, licensed medical professional or appropriate health care provider about the applicability of any opinions or recommendations with respect to your own symptoms or medical conditions. The researchers, writers and editors at PHI NATURAL HEALTH INTERNATIONAL LTD are not doctors, and shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss, damage, or injury caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information provided. No representation or warranties of any kind are made with regard to completeness or accuracy of the information. Quotations are used as 'fair use' to illustrate various points made. Quoted text may be subject to copyright owned by third parties.