Accepted Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Destinées De L'illyricum Méridional Pendant Le Haut Moyen Âge

JOBNAME: No Job Name PAGE: 1 SESS: 12 OUTPUT: Thu May 26 16:08:52 2011 SUM: 6023F8EF /v2451/blackwell/journals/emed_v19_i3/05emed_324 1 Book reviewsemed_324 354..376 2 3 Les destinées de l’Illyricum méridional pendant le haut Moyen Âge. 4 Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome, Moyen Âge 120–2. Rome: 5 l’École Française de Rome. 2009. 238 pp. + 50 b/w and 101 color figures. 6 EUR 55. ISBN 978 2 7283 0870 5; ISSN 0223 9883. 7 8 This is the proceedings of a conference jointly organized by École 9 française de Rome, Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, and 10 the Albanian Institute of Archaeology in Lezha (Albania) in 2008.In 11 the introduction, Etleva Nallbani explains its main objective as throw- 12 ing new light on developments in the Western Balkans during the early 13 Middle Ages, primarily on the basis of archaeological research con- 14 ducted in the past two decades. The present volume witnesses not only 15 the technological advances in archaeology, which can be seen at work in 16 a number of contributions, but it also bears the mark of a renewed 17 interest in rural settlements and the relative departure from political 18 history in favour of detailed analyses of production, distribution, and 19 exchange routes. 20 Rather than summarize the wealth of insights in a short space, I will 21 focus on two major themes addressed by this volume: urban and rural life 22 in Illyricum and patterns of production and distribution. Pascale Cheva- 23 lier and Jagoda Mardešic´ contribute an insightful piece on urban life at 24 Salona during the sixth–seventh centuries based on the recent excavations 25 conducted in the episcopal complex of the town. -

Marriage: a Meaningful Relationship? In: Eekelaar, J. (Ed.) Family Law in Britain and America in the New Century

Mair, J. (2016) Marriage: a meaningful relationship? In: Eekelaar, J. (ed.) Family Law in Britain and America in the New Century. Brill Nijhoff. ISBN 9789004304918. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/120966/ Deposited on: 02 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Marriage: a meaningful relationship? For family lawyers with an interest in marriage, the latter decades of the 20th Century were lean times. Marriage was a settled subject. From the 19th Century Married Women’s Property Acts through to no-fault divorce and financial provision in the 1970s and 80s, a century of legal reform had groomed a somewhat aged model and made it suitably modern for contemporary family law.1 Nagging doubts remained about declining social relevance, accompanied by growing interest in alternative relationships, but these were concerns which tended to divert our gaze away from marriage itself and towards the other, newer possibilities: cohabitation, civil union, Pacs, 2 mother/child dyad, 3 friendship. 4 Marriage itself attracted relatively little attention. Then into that quiet and settled landscape, there blew “a perfect storm.”5 At the centre of the storm was same sex marriage but, caught up along with it, were calls and concerns from every perspective: conservative, liberal, religious, secular, feminist, functional, expressive. 6 Far from being calm, settled and slightly overlooked, marriage has become fiercely contested and deeply controversial. Marriage is now at the centre of a struggle between conservatives and liberals, those who wish to preserve and those who wish to reform but, no matter the particular perspective or 1 For an overview of this period of modernisation throughout Europe, see M Antokolskaia, Harmonisation of Family Law in Europe: A Historical Perspective, 2006, Intersentia, chapter 13. -

Marriage Laws Around the World

1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Marriage Laws around the World COUNTRY CODED TEXT Source Additional sources Despite a law setting the legal minimum age for marriage at 16 (15 with the consent of a parent or guardian and the court) for girls and 18 for boys, international and local observers continued to report widespread early marriage. The media reported a 2014 survey by the Ministry of Public Health that sampled 24,032 households in all 34 provinces showed 53 percent of all women ages 25-49 married by age 18 and 21 percent by age 15. According to the Central Statistics Organization of Afghanistan, 17.3 percent of girls ages 15 to 19 and 66.2 percent of girls ages 20 to 24 were married. During the EVAW law debate, conservative politicians publicly stated it was un-Islamic to ban the marriage of girls younger than 16. Under the EVAW law, those who arrange forced or underage marriages may be sentenced to imprisonment for not less than two years, but implementation of the law remained limited. The Law on Marriage states marriage of a minor may be conducted with a guardian’s consent. By law a marriage contract requires verification that the bride is 16 years of age, but only a small fraction of the population had birth certificates. Following custom, some poor families pledged their daughters to marry in exchange for “bride money,” although the practice is illegal. According to local NGOs, some girls as young as six or seven were promised in marriage, with the understanding the actual marriage would be delayed until the child [Source: Department of reached puberty. -

Marriage Venues

By Catherine Fairbairn 6 July 2021 Marriage venues Summary 1 Where can a marriage take place in England and Wales? 2 Civil marriage 3 Religious marriage 4 The Labour Government’s proposals (1999-2005) 5 Law Commission project on weddings 6 Marriage venues in Scotland commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number 02842 Marriage venues Image Credits Attributed to: ring / yüzük by M. G. Kafkas. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. Please note that authors are not always able to engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and correct any factual errors. -

During the Middle of the 18Th Century an Intellectual Revolution Took Place in Scotland That Still Has Resonance and Impact Today

SCOTTISH ENLIGHTENMENT A BRILLIANCE THAT RADIATES 300 YEARS ON During the middle of the 18th century an intellectual revolution took place in Scotland that still has resonance and impact today WORDS: Stewart McRobert 16 | DISCOVER | SUMMER 2019 he Scottish Enlightenment It coincides with a meeting of the was an outburst of ideas International Society for Eighteenth- covering an array of Century Studies which takes place in disciplines, from geology and Edinburgh in July. engineering to architecture, This sees 1,500 academics from A BRILLIANCE philosophy, medicine, around the world discuss the wider Age Teconomics and the law. They were of Enlightenment, which encompasses developed by people whose thoughts and developments in Europe and the United achievements are still celebrated around States. As part of this congress, the the world – Adam Smith, David Hume, Library is undertaking a joint event with Robert Burns, James Hutton, James Watt the Society and has commissioned THAT RADIATES and many others. work by postgraduate students who will A major National Library of Scotland further explore Library collections that exhibition – Northern Lights, beginning relate to the Scottish Enlightenment. on 21 June and running through to One of those curating the main April 2020 – celebrates the Scottish exhibition, Ralph McLean, Manuscripts 300 YEARS ON Enlightenment and its key figures. Curator (Long 18th-Century Collections), FIGURES OF HISTORY: From left: David Hume, Robert Burns, Adam Smith and James Watt SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 17 SCOTTISH ENLIGHTENMENT revealed that the Library has been observed: “Here I stand at what is the was vital. They include Alison Cockburn. collecting material relating to the Scottish Cross of Edinburgh, and can, in a few She was a literary hostess and writer – Enlightenment since the movement was minutes, take 50 men of genius and her version of the Scots song The Flowers in progress. -

Worship on the Web

Worship on the Web FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (marriage) Please note this advice applies to getting in married in Scotland. For a wedding in a Church of Scotland church in England, the law may be different and the minister should be contacted early on to ensure legal requirements there can be met. Questions about marriage in the Church of Scotland 1. Can anyone be married in a Church of Scotland church? 2. Can divorced people be remarried in the Church of Scotland? 3. Can people come from outwith Scotland to be married in a Church of Scotland church? 4. Can a minister of another Church conduct a wedding in Scotland? 5. Is it true that a minister can marry a couple anywhere? 6. What should I do next? 7. What if I am marrying a Roman Catholic? Q. Can anyone be married in a Church of Scotland church? A. The Church of Scotland is 'national', in that every district has its parish church. The parish minister is willing to discuss conducting marriage for any member of the parish. If you are not a church member, the minister will want to discuss with you whether a religious ceremony is what you are looking for, whether it will have meaning for you, and whether he or she agrees it is appropriate in your situation. Q. Can divorced people be remarried in the Church of Scotland? A. Marriage is not understood in the Church of Scotland to be a sacrament, and therefore binding for ever. A minister may therefore conduct the marriage of a divorced person whose former spouse is still alive. -

Heather Parker

“In all gudly haste”: The Formation of Marriage in Scotland, c. 1350-1600 by Heather Parker A thesis presented to the University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philsophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Heather Parker, March 2012 ABSTRACT “IN ALL GUDLY HASTE”: THE FORMATION OF MARRIAGE IN SCOTLAND, C. 1350-1600 Heather Parker Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Elizabeth Ewan This dissertation examines the formation of marriage in Scotland between the mid- fourteenth century and the late sixteenth century. In particular, it focuses on betrothals, marriage negotiations, ritual, and the place that these held in late medieval Scottish society. This study extends to the generation following the Reformation to examine the extent to which the Reformation influenced the marriage planning of wealthy Scots. It concludes that much of the social impact of the Reformation was not reflected in family life until at least a generation after reform. Scottish society and culture was influenced both by contemporary literature, which discussed the role of marriage formation, and by concurrent events involving high-profile marriages. These helped to define the context of marriage for society as a whole. This work relies heavily on the pre-nuptial contracts of lairds (the Scottish gentry) and nobles, which reflected certain aspects of their marriage patterns and strategies. The context and clauses of an extensive group of 272 Scottish marriage contracts from published and archival collections illuminate aspects of the formation of Scottish marriage, such as the land and money that changed hands, the extent to which brides and grooms were influenced by their kin, and the timelines for betrothals. -

Explanatory Notes

This document relates to the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill as amended at Stage 2 (SP Bill 36A) MARRIAGE AND CIVIL PARTNERSHIP (SCOTLAND) BILL [AS AMENDED AT STAGE 2] —————————— REVISED EXPLANATORY NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. As required under Rule 9.7.8A of the Parliament‘s Standing Orders, these Revised Explanatory Notes are published to accompany the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill (introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 26 June 2013) as amended at Stage 2. Text has been added or deleted as necessary to reflect the amendments made to the Bill at Stage 2 and these changes are indicated by sidelining in the right margin. 2. These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Scottish Government in order to assist the reader of the Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by the Parliament. 3. The Notes should be read in conjunction with the Bill. They are not, and are not meant to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. So where a section or schedule, or a part of a section or schedule, does not seem to require any explanation or comment, none is given. THE BILL 4. The draft Bill proposes a number of amendments to the Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977 and the Civil Partnership Act 2004. These Acts are referred to in these Explanatory Notes as ―the 1977 Act‖ and ―the 2004 Act‖. Summary and background 5. Key matters covered by the Bill are: the introduction of same sex marriage, so that same sex couples can marry each other; putting belief celebrants on -

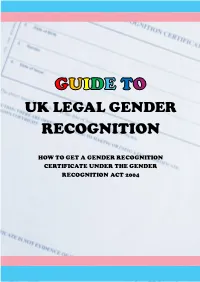

Gender Recognition Guide

UK LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITION HOW TO GET A GENDER RECOGNITION CERTIFICATE UNDER THE GENDER RECOGNITION ACT 2004 Key to colours used Most of this guide applies to everyone, but some parts are specific to certain countries. We highlight these sections using text but also colours: Red sections are specific to people who are living in England or Wales, or sometimes to people who entered into a marriage or civil partnership in England or Wales. Blue sections are specific to people who are living in Scotland, or sometimes to people who entered into a marriage or civil partnership in Scotland. Green sections are specific to people who are living in Northern Ireland, or sometimes to people who entered into a marriage or civil partnership in Northern Ireland. Purple sections are specific to people who are living outside of the UK (including the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man), or sometimes to people who entered into a marriage or civil partnership outside of the UK. This guide was made by UK Trans Info, a national organisation that works to improve the lives of trans and non-binary people in the UK through advocacy, campaigning, information and support. www.uktrans.info This guide was funded by Scottish Transgender Alliance, the Equality Network project to improve gender identity and gender reassignment equality, rights and inclusion in Scotland. www.scottishtrans.org 2 UK LEGAL GENDER RECOGNITION Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 What is gender recognition? ................................................................................................. 5 What are the legal effects of gender recognition? ........................................................... 6 What if you already have your gender recognised in another country? .................... -

Scotland's Population

Scotland's Population The Registrar General's Annual Review of Demographic Trends 2017 163rd Edition Scotland’s population – The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends © Crown copyright and database right 2018. Ordnance Survey (OS Licence number 100020542). © Crown Copyright 2018 Scotland’s population – The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends Annual Report of the Registrar General of Births, Deaths and Marriages for Scotland 2017 rd 163 Edition To Scottish Ministers I am pleased to present to you my Annual Report for the year 2017, which will be laid before the Scottish Parliament pursuant to Section 1(4) of the Registration of Births, Deaths and Marriages (Scotland) Act 1965. Anne Slater Registrar General for Scotland 1 August 2018 Published 1 August 2018 SG/2018/90 © Crown Copyright 2018 Scotland’s population – The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends © Crown Copyright 2018 Scotland’s population – The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends Contents Page Foreword......................................................................................................................................................7 Headline Messages.…………………………………...………………………………………………………...……9 Chapter 1 – Population…...………………….……...………...………...…………………………….23 Chapter 2 – Births…………………..……....………...……………………………………….…….…….39 Chapter 3 – Deaths………………..……...………...……...…………………………………….……….51 Chapter 4 – Life expectancy……….…….….………...………..….……………….……………….69 Chapter 5 – Migration……………………...…….……...………...……...………..………………….81 -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised Version of the Original Print Thesis. Copyright and Moral

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] WOMEN OF THE SCOTTISH ENLIGHTENMENT : THEIR IMPORTANCE IN THE HISTORY OF SCOTTISH EDUCATION BY ROSALIND RUSSELL M.A., Dip.Ed., M.Ed. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. The University of Glasgow DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW February, 1988 Copyright Rosalind Russell 1988 ProQuest Number: 10997952 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10997952 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Forced Marriage Etc. (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Bill 22 November 2010 10/79 Lisa Taylor the Forced Marriage Etc

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament Infor mation C entre l ogos. SPICe Briefing Forced Marriage etc. (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Bill 22 November 2010 10/79 Lisa Taylor The Forced Marriage etc. (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Bill was introduced in the Scottish Parliament by Nicola Sturgeon MSP on 29 September 2010. The Bill proposes new civil measures for preventing people from being forced to enter into marriage without their free and full consent and for protecting those who have been forced to enter into marriage without such consent. The Bill would give those who fear being married against their will the right to apply to a civil court for a Forced Marriage Protection Order (FMPO). It also makes provision as to the jurisdictional rules applying in the sheriff court in relation to declarators of nullity of marriage. This briefing is in three parts: background on the issue of forced marriage, existing legal protection for victims of forced marriage; and a discussion of the main provisions in the Bill itself. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 PART 1: BACKGROUND TO FORCED MARRIAGE ................................................................................................. 5 DEFINITION OF FORCED