Human Gnathostomiasis: a Neglected Food-Borne Zoonosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gnathostoma Spinigerum Was Positive

Department Medicine Diagnostic Centre Swiss TPH Winter Symposium 2017 Helminth Infection – from Transmission to Control Sushi Worms – Diagnostic Challenges Beatrice Nickel Fish-borne helminth infections Consumption of raw or undercooked fish - Anisakis spp. infections - Gnathostoma spp. infections Case 1 • 32 year old man • Admitted to hospital with severe gastric pain • Abdominal pain below ribs since a week, vomiting • Low-grade fever • Physical examination: moderate abdominal tenderness • Laboratory results: mild leucocytosis • Patient revealed to have eaten sushi recently • Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed Carmo J, et al. BMJ Case Rep 2017. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-218857 Case 1 Endoscopy revealed 2-3 cm long helminth Nematode firmly attached to / Endoscopic removal of larva with penetrating gastric mucosa a Roth net Carmo J, et al. BMJ Case Rep 2017. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-218857 Anisakiasis Human parasitic infection of gastrointestinal tract by • herring worm, Anisakis spp. (A.simplex, A.physeteris) • cod worm, Pseudoterranova spp. (P. decipiens) Consumption of raw or undercooked seafood containing infectious larvae Highest incidence in countries where consumption of raw or marinated fish dishes are common: • Japan (sashimi, sushi) • Scandinavia (cod liver) • Netherlands (maatjes herrings) • Spain (anchovies) • South America (ceviche) Source: http://parasitewonders.blogspot.ch Life Cycle of Anisakis simplex (L1-L2 larvae) L3 larvae L2 larvae L3 larvae Source: Adapted to Audicana et al, TRENDS in Parasitology Vol.18 No. 1 January 2002 Symptoms Within few hours of ingestion, the larvae try to penetrate the gastric/intestinal wall • acute gastric pain or abdominal pain • low-grade fever • nausea, vomiting • allergic reaction possible, urticaria • local inflammation Invasion of the third-stage larvae into gut wall can lead to eosinophilic granuloma, ulcer or even perforation. -

Toxocariasis: a Rare Cause of Multiple Cerebral Infarction Hyun Hee Kwon Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu, Korea

Case Report Infection & http://dx.doi.org/10.3947/ic.2015.47.2.137 Infect Chemother 2015;47(2):137-141 Chemotherapy ISSN 2093-2340 (Print) · ISSN 2092-6448 (Online) Toxocariasis: A Rare Cause of Multiple Cerebral Infarction Hyun Hee Kwon Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu, Korea Toxocariasis is a parasitic infection caused by the roundworms Toxocara canis or Toxocara cati, mostly due to accidental in- gestion of embryonated eggs. Clinical manifestations vary and are classified as visceral larva migrans or ocular larva migrans according to the organs affected. Central nervous system involvement is an unusual complication. Here, we report a case of multiple cerebral infarction and concurrent multi-organ involvement due to T. canis infestation of a previous healthy 39-year- old male who was admitted for right leg weakness. After treatment with albendazole, the patient’s clinical and laboratory results improved markedly. Key Words: Toxocara canis; Cerebral infarction; Larva migrans, visceral Introduction commonly involved organs [4]. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is relatively rare in toxocariasis, especially CNS Toxocariasis is a parasitic infection caused by infection with presenting as multiple cerebral infarction. We report a case of the roundworm species Toxocara canis or less frequently multiple cerebral infarction with lung and liver involvement Toxocara cati whose hosts are dogs and cats, respectively [1]. due to T. canis infection in a previously healthy patient who Humans become infected accidentally by ingestion of embry- was admitted for right leg weakness. onated eggs from contaminated soil or dirty hands, or by in- gestion of raw organs containing encapsulated larvae [2]. -

Review Articles Neuroinvasions Caused by Parasites

Annals of Parasitology 2017, 63(4), 243–253 Copyright© 2017 Polish Parasitological Society doi: 10.17420/ap6304.111 Review articles Neuroinvasions caused by parasites Magdalena Dzikowiec 1, Katarzyna Góralska 2, Joanna Błaszkowska 1 1Department of Diagnostics and Treatment of Parasitic Diseases and Mycoses, Medical University of Lodz, ul. Pomorska 251 (C5), 92-213 Lodz, Poland 2Department of Biomedicine and Genetics, Medical University of Lodz, ul. Pomorska 251 (C5), 92-213 Lodz, Poland Corresponding Author: Joanna Błaszkowska; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Parasitic diseases of the central nervous system are associated with high mortality and morbidity. Many human parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii , Entamoeba histolytica , Trypanosoma cruzi , Taenia solium , Echinococcus spp., Toxocara canis , T. cati , Angiostrongylus cantonensis , Trichinella spp., during invasion might involve the CNS. Some parasitic infections of the brain are lethal if left untreated (e.g., cerebral malaria – Plasmodium falciparum , primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) – Naegleria fowleri , baylisascariosis – Baylisascaris procyonis , African sleeping sickness – African trypanosomes). These diseases have diverse vectors or intermediate hosts, modes of transmission and endemic regions or geographic distributions. The neurological, cognitive, and mental health problems caused by above parasites are noted mostly in low-income countries; however, sporadic cases also occur in non-endemic areas because of an increase in international travel and immunosuppression caused by therapy or HIV infection. The presence of parasites in the CNS may cause a variety of nerve symptoms, depending on the location and extent of the injury; the most common subjective symptoms include headache, dizziness, and root pain while objective symptoms are epileptic seizures, increased intracranial pressure, sensory disturbances, meningeal syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, and core syndromes. -

Molecular Identification of the Etiological Agent of Human

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 73, 44–50, 2020 Original Article Molecular Identification of the Etiological Agent of Human Gnathostomiasis in an Endemic Area of Mexico Sylvia Paz Díaz-Camacho1, Jesús Ricardo Parra-Unda2, Julián Ríos-Sicairos2, and Francisco Delgado-Vargas2* 1Research Unit in Environment and Health, Autonomous University of Occident, Sinaloa; and 2Public Health Research Unit "Dra. Kaethe Willms", School of Chemical and Biological Sciences, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, University city, Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico SUMMARY: Human gnathostomiasis, which is endemic in Mexico, is a worldwide health concern. It is mainly caused by the consumption of raw or insufficiently cooked fish containing the advanced third-stage larvae (AL3A) of Gnathostoma species. The diagnosis of gnathostomiasis is based on epidemiological surveys and immunological diagnostic tests. When a larva is recovered, the species can be identified by molecular techniques. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the second internal transcription spacer (ITS-2) is useful to identify nematode species, including Gnathostoma species. This study aims to develop a duplex-PCR amplification method of the ITS-2 region to differentiate between the Gnathostoma binucleatum and G. turgidum parasites that coexist in the same endemic area, as well as to identify the Gnathostoma larvae recovered from the biopsies of two gnathostomiasis patients from Sinaloa, Mexico. The duplex PCR established based on the ITS- 2 sequence showed that the length of the amplicons was 321 bp for G. binucleatum and 226 bp for G. turgidum. The amplicons from the AL3A of both patients were 321 bp. Furthermore, the length and composition of these amplicons were identical to those deposited in GenBank as G. -

Gnathostomiasis: an Emerging Imported Disease David A.J

RESEARCH Gnathostomiasis: An Emerging Imported Disease David A.J. Moore,* Janice McCroddan,† Paron Dekumyoy,‡ and Peter L. Chiodini† As the scope of international travel expands, an ous complication of central nervous system involvement increasing number of travelers are coming into contact with (4). This form is manifested by painful radiculopathy, helminthic parasites rarely seen outside the tropics. As a which can lead to paraplegia, sometimes following an result, the occurrence of Gnathostoma spinigerum infection acute (eosinophilic) meningitic illness. leading to the clinical syndrome gnathostomiasis is increas- We describe a series of patients in whom G. spinigerum ing. In areas where Gnathostoma is not endemic, few cli- nicians are familiar with this disease. To highlight this infection was diagnosed at the Hospital for Tropical underdiagnosed parasitic infection, we describe a case Diseases, London; they were treated over a 12-month peri- series of patients with gnathostomiasis who were treated od. Four illustrative case histories are described in detail. during a 12-month period at the Hospital for Tropical This case series represents a small proportion of gnathos- Diseases, London. tomiasis patients receiving medical care in the United Kingdom, in whom this uncommon parasitic infection is mostly undiagnosed. he ease of international travel in the 21st century has resulted in persons from Europe and other western T Methods countries traveling to distant areas of the world and return- The case notes of patients in whom gnathostomiasis ing with an increasing array of parasitic infections rarely was diagnosed at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases were seen in more temperate zones. One example is infection reviewed retrospectively for clinical symptoms and confir- with Gnathostoma spinigerum, which is acquired by eating uncooked food infected with the larval third stage of the helminth; such foods typically include fish, shrimp, crab, crayfish, frog, or chicken. -

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

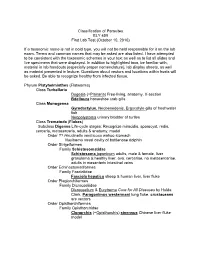

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Parascaris Univalens After in Vitro Exposure to Ivermectin, Pyrantel Citrate and Thiabendazole

Transcriptional responses in Parascaris univalens after in vitro exposure to ivermectin, pyrantel citrate and thiabendazole Frida Martin ( [email protected] ) Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3149-3835 Faruk Dube Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Veterinarmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Oskar Karlsson Lindsjö Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Veterinarmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Matthías Eydal Haskoli Islands Johan Höglund Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Veterinarmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Tomas F. Bergström Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Veterinarmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Eva Tydén Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Veterinarmedicin och husdjursvetenskap Research Keywords: transcriptome, anthelmintic resistance, RNA sequencing, differential expression, lgc-37 Posted Date: March 18th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-17857/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on July 9th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04212-0. Page 1/23 Abstract Background: Parascaris univalens is a pathogenic parasite of foals and yearlings worldwide. In recent years Parascaris spp. worms have developed resistance to several of the commonly used anthelmintics, though currently the mechanisms behind this development is unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the transcriptional responses in adult P. univalens worms after in vitro exposure -

Worms, Nematoda

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2001 Worms, Nematoda Scott Lyell Gardner University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Gardner, Scott Lyell, "Worms, Nematoda" (2001). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 5 (2001): 843-862. Copyright 2001, Academic Press. Used by permission. Worms, Nematoda Scott L. Gardner University of Nebraska, Lincoln I. What Is a Nematode? Diversity in Morphology pods (see epidermis), and various other inverte- II. The Ubiquitous Nature of Nematodes brates. III. Diversity of Habitats and Distribution stichosome A longitudinal series of cells (sticho- IV. How Do Nematodes Affect the Biosphere? cytes) that form the anterior esophageal glands Tri- V. How Many Species of Nemata? churis. VI. Molecular Diversity in the Nemata VII. Relationships to Other Animal Groups stoma The buccal cavity, just posterior to the oval VIII. Future Knowledge of Nematodes opening or mouth; usually includes the anterior end of the esophagus (pharynx). GLOSSARY pseudocoelom A body cavity not lined with a me- anhydrobiosis A state of dormancy in various in- sodermal epithelium. -

Monophyly of Clade III Nematodes Is Not Supported by Phylogenetic Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7509r5vp Journal BMC Genomics, 12(1) ISSN 1471-2164 Authors Park, Joong-Ki Sultana, Tahera Lee, Sang-Hwa et al. Publication Date 2011-08-03 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-392 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Park et al. BMC Genomics 2011, 12:392 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/392 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Joong-Ki Park1*, Tahera Sultana2, Sang-Hwa Lee3, Seokha Kang4, Hyong Kyu Kim5, Gi-Sik Min2, Keeseon S Eom6 and Steven A Nadler7 Abstract Background: The orders Ascaridida, Oxyurida, and Spirurida represent major components of zooparasitic nematode diversity, including many species of veterinary and medical importance. Phylum-wide nematode phylogenetic hypotheses have mainly been based on nuclear rDNA sequences, but more recently complete mitochondrial (mtDNA) gene sequences have provided another source of molecular information to evaluate relationships. Although there is much agreement between nuclear rDNA and mtDNA phylogenies, relationships among certain major clades are different. In this study we report that mtDNA sequences do not support the monophyly of Ascaridida, Oxyurida and Spirurida (clade III) in contrast to results for nuclear rDNA. Results from mtDNA genomes show promise as an additional independently evolving genome for developing phylogenetic hypotheses for nematodes, although substantially increased taxon sampling is needed for enhanced comparative value with nuclear rDNA. -

The P-Glycoprotein Repertoire of the Equine Parasitic Nematode Parascaris Univalens

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The P‑glycoprotein repertoire of the equine parasitic nematode Parascaris univalens Alexander P. Gerhard1, Jürgen Krücken1, Emanuel Heitlinger2,3, I. Jana I. Janssen1, Marta Basiaga4, Sławomir Kornaś4, Céline Beier1, Martin K. Nielsen5, Richard E. Davis6, Jianbin Wang6,7 & Georg von Samson‑Himmelstjerna1* P-glycoproteins (Pgp) have been proposed as contributors to the widespread macrocyclic lactone (ML) resistance in several nematode species including a major pathogen of foals, Parascaris univalens. Using new and available RNA-seq data, ten diferent genomic loci encoding Pgps were identifed and characterized by transcriptome‑guided RT-PCRs and Sanger sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis revealed an ascarid-specifc Pgp lineage, Pgp-18, as well as two paralogues of Pgp-11 and Pgp-16. Comparative gene expression analyses in P. univalens and Caenorhabditis elegans show that the intestine is the major site of expression but individual gene expression patterns were not conserved between the two nematodes. In P. univalens, PunPgp-9, PunPgp-11.1 and PunPgp-16.2 consistently exhibited the highest expression level in two independent transcriptome data sets. Using RNA-Seq, no signifcant upregulation of any Pgp was detected following in vitro incubation of adult P. univalens with ivermectin suggesting that drug-induced upregulation is not the mechanism of Pgp-mediated ML resistance. Expression and functional analyses of PunPgp-2 and PunPgp-9 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae provide evidence for an interaction with ketoconazole and ivermectin, but not thiabendazole. Overall, this study established reliable reference gene models with signifcantly improved annotation for the P. univalens Pgp repertoire and provides a foundation for a better understanding of Pgp‑mediated anthelmintic resistance. -

The Phylogenetics of Anguillicolidae (Nematoda: Anguillicolidea), Swimbladder Parasites of Eels

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title The phylogenetics of Anguillicolidae (Nematoda: Anguillicolidea), swimbladder parasites of eels Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3017p5m4 Journal BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(1) ISSN 1471-2148 Authors Laetsch, Dominik R Heitlinger, Emanuel G Taraschewski, Horst et al. Publication Date 2012-05-04 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-60 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The phylogenetics of Anguillicolidae (Nematoda: Anguillicoloidea), swimbladder parasites of eels Laetsch et al. Laetsch et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2012, 12:60 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/12/60 Laetsch et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2012, 12:60 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/12/60 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The phylogenetics of Anguillicolidae (Nematoda: Anguillicoloidea), swimbladder parasites of eels Dominik R Laetsch1,2*, Emanuel G Heitlinger1,2, Horst Taraschewski1, Steven A Nadler3 and Mark L Blaxter2 Abstract Background: Anguillicolidae Yamaguti, 1935 is a family of parasitic nematode infecting fresh-water eels of the genus Anguilla, comprising five species in the genera Anguillicola and Anguillicoloides. Anguillicoloides crassus is of particular importance, as it has recently spread from its endemic range in the Eastern Pacific to Europe and North America, where it poses a significant threat to new, naïve hosts such as the economic important eel species Anguilla anguilla and Anguilla rostrata. The Anguillicolidae are therefore all potentially invasive taxa, but the relationships of the described species remain unclear. Anguillicolidae is part of Spirurina, a diverse clade made up of only animal parasites, but placement of the family within Spirurina is based on limited data. -

Transcriptional Responses in Parascaris

Martin et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:342 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04212-0 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Transcriptional responses in Parascaris univalens after in vitro exposure to ivermectin, pyrantel citrate and thiabendazole Frida Martin1* , Faruk Dube1, Oskar Karlsson Lindsjö2, Matthías Eydal3, Johan Höglund1, Tomas F. Bergström4 and Eva Tydén1 Abstract Background: Parascaris univalens is a pathogenic parasite of foals and yearlings worldwide. In recent years, Parascaris spp. worms have developed resistance to several of the commonly used anthelmintics, though currently the mecha- nisms behind this development are unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the transcriptional responses in adult P. univalens worms after in vitro exposure to diferent concentrations of three anthelmintic drugs, focusing on drug targets and drug metabolising pathways. Methods: Adult worms were collected from the intestines of two foals at slaughter. The foals were naturally infected and had never been treated with anthelmintics. Worms were incubated in cell culture media containing diferent 9 11 13 6 8 10 concentrations of either ivermectin (10− M, 10− M, 10− M), pyrantel citrate (10− M, 10− M, 10− M), thiaben- 5 7 9 dazole (10− M, 10− M, 10− M) or without anthelmintics (control) at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the viability of the worms was assessed and RNA extracted from the anterior region of 36 worms and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system. Results: All worms were alive at the end of the incubation but