Party Consolidation and Representative Democracy in Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

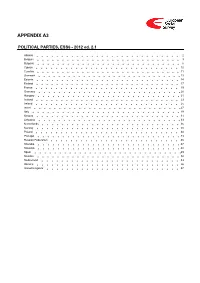

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Kosovar Culture Introduction

” • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •Islam in Kosovo has a long standing tradition dating back to the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, including Kosovo. •Before the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, the entire Balkan region had been Christianized by both the Roman and Byzantine Empires. •From 1389 until 1912, Kosovo was officially governed by the Muslim Ottoman Empire and, as such, a high level ofIslamization occurred. •During the time period after World War II, Kosovo was ruled by secular socialist authorities in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). •During that period, Kosovars became increasingly secularized. •Today, 90% of Kosovo's population is at least nominally Muslim, most of whom are Albanian.[1] • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other. - Mother Teresa Mother Teresa was born (1910) Due to her commitment and humanitarian activity, Mother Teresa was The recipient of prestigious awards: • The first Pope John XXIII Peace Prize. (1971) • Kennedy Prize (1971) • The Nehru Prize –“for promotion of international peace and understanding”(1972) • Albert Schweitzer International Prize (1975), • The Nobel Peace Prize (1979) • States Presidential Medal of Freedom (1985) • Congressional Gold Medal (1994) • Honorary citizenship of the United States (November 16, 1996), From the Inter-religious conference in Vienna, March 16-18, 1999 (from left to right: Myfti Qemajl Morina, Bishop Artemije, late Bishop -

Thesis Submission

CIVIC NATION BUILDING AS A TOOL FOR CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION: AN ANALYSIS OF THE AHTISAARI PLAN AND THE INDEPENDENCE PROCESS IN KOSOVO by Natalia Andrea Peral Submitted to Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Analysis and Resolution Sabancı University June 2009 CIVIC NATION BUILDING AS A TOOL FOR CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION: AN ANALYSIS OF THE AHTISAARI PLAN AND THE INDEPENDENCE PROCESS IN KOSOVO APPROVED BY: Prof. Fikret Adanır ……………………………….. (Thesis Supervisor) Assoc. Prof. Nimet Beriker …………………………. Assist.Prof. Riva Kantowitz …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: …………………………. ii © Natalia Andrea Peral All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT CIVIC NATION BUILDING AS TOOL FOR CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION: AN ANALYSIS OF THE AHTISAARI PLAN AND THE INDEPENDENCE PROCESS IN KOSOVO by Natalia Andrea Peral M.A. in Conflict Analysis and Resolution Supervisor: Prof. Fikret Adanır Keywords: Kosovo, Ahtisaari Plan, Civic Nation, Nation Building, Third Party Intervention, Conflict Transformation. This study investigates the civic nation building (CNB) process initiated by Ahtisaari Plan in Kosovo from a Conflict Resolution perspective. I treat nation building efforts of external actors as a form of structural third party intervention in post conflict and multi-ethnic divided societies, and I observe whether this process contributes to the transformation of the conflict. Special focus is placed on the Decentralization Laws and Special Protective Zones Law of Ahtisaari‘s Package and their impact on the relationships between Kosovo Albanians and Kosovo Serbs. Concretely, I examine whether the mechanisms provided by these laws contributed to transform the interethnic iv relations based on competing nationalistic projects. For this purpose I study conflict transformations at structure, issue, actor and personal level. -

Governance with Integrity

GOVERNANCE WITH INTEGRITY Comparative Report of Candidates with Indictments in Election Lists 2010, 2014 and 2017 GOVERNANCE WITH INTEGRITY What Candidates are Parties Offering in 2019! Comparative Report of Candidates with Indictments in Election Lists 2010, 2014 and 2017 Prishtina September 2019 Author: Kosovo Law Institute (KLI) for the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, funded by the Government of the United Kingdom. No part of this report may be printed, copied, multiplied in any form, be it electronic or printed, or in another other way of multiplication without the consent of the Kosovo Law Institute and the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. The content of this publication is an exclusive responsibility of the KLI and it does not represent the views of the donor. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6 International practice and legal basis in Kosovo ............................................................. 7 1. Legislative prohibition ..................................................................................... 7 2. Institutional exclusion. ..................................................................................... 7 3. Rules and policies within political parties. ....................................................... 7 Political Party Election Lists with Candidates -

Major Political Parties Coverage for Data Collection 2021 Country Major

Major political parties Coverage for data collection 2021 Country Major political parties EU Member States Christian Democratic and Flemish (Chrétiens-démocrates et flamands/Christen-Democratisch Belgium en Vlaams/Christlich-Demokratisch und Flämisch) Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste/Socialistische Partij/Sozialistische Partei) Forward (Vooruit) Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten) Reformist Movement (Mouvement Réformateur) New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) Ecolo Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) Workers' Party of Belgium (Partij van de Arbeid van België) Green Party (Groen) Bulgaria Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (Grazhdani za evropeysko razvitie na Balgariya) Bulgarian Socialist Party (Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya) Movement for Rights and Freedoms (Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi) There is such people (Ima takav narod) Yes Bulgaria ! (Da Bulgaria!) Czech Republic Mayors and Independents STAN (Starostové a nezávislí) Czech Social Democratic Party (Ceská strana sociálne demokratická) ANO 2011 Okamura, SPD) Denmark Liberal Party (Venstre) Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne/Socialdemokratiet) Danish People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti) Unity List-Red Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) Socialist People's Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti) Conservative People's Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) Germany Christian-Democratic Union of Germany (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) Christian Social Union in Bavaria (Christlich-Soziale -

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

NIT-2011-Kosovo- 0.Pdf

Kosovo by Ariana Qosaj-Mustafa Capital: Pristina Population: 1.8 million GNI/capita, PPP: n/a Source: !e data above was provided by !e World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores Yugoslavia Kosovo 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Electoral Process 3.75 3.75 5.25 4.75 4.75 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.25 4.50 Civil Society 3.00 2.75 4.25 4.00 4.25 4.25 4.00 4.00 3.75 3.75 Independent Media 3.50 3.25 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.75 Governance* 4.25 4.25 6.00 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic 5.75 Governance n/a n/a n/a 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.25 5.50 Local Democratic 5.00 Governance n/a n/a n/a 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.50 5.25 5.00 Judicial Framework 5.75 and Independence 4.25 4.25 6.00 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 Corruption 5.25 5.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 Democracy Score 4.00 3.88 5.50 5.32 5.36 5.36 5.21 5.14 5.07 5.18 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

UNTYING the KOSOVO KNOT a Two-Sided View Helsinki FILES No

Helsinki FILES No. 20 UNTYING THE KOSOVO KNOT A Two-Sided View Helsinki FILES No. 20 UNTYING THE KOSOVO KNOT A Two-Sided View Publisher: Helsinki Commi�ee for Human Rights in Serbia For Publisher: Sonja Biserko *** Editor: Seška Stanojlović Authors: Fahri Musliu Dragan Banjac Translated by: Ivana Damjanović Dragan Novaković Cover Page: UNTYING THE KOSOVO KNOT Ivan Hrašovec A Two-Sided View Printed by: Zagorac, Belgrade, 2005 Number of copies: 500 ISBN: 86-7208-111-0 *** This book of interviews has been published within the projecet “Belgrade- Prishtina: Steps to Build Confidence and Understanding” and with the support of the United States Institute of Peace. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of inteviewees and other sources, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. The Helsinki Commi�ee for Human Rights in Serbia thanks the DFA Federal Department of Foreign Affairs - Swiss Liaison Office in Kosovo for its assistance in having this book translated into English. The opinions expressed herein are those of the persons interviewd and other sources, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Swiss Liaison Office. Contents: Editor’s foreword: Framework for Talks ........................................... 7 The author’s preface ............................................................................. 9 Serbian Side Vuk Draskovic ....................................................................................... 13 Goran Svilanovic -

Political Parties and Consolidation of Democracy in Kosovo

Ailing the Process: Political Parties and Consolidation of Democracy in Kosovo Vom Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil. genehmigte Dissertation von Smajljaj, Avdi aus Prishtinë (Llazarevë) 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Schmitt-Beck, Rüdiger 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Poguntke, Thomas Tag der Disputation: 07.02.2011 Ailing the process: political parties and consolidation of democracy in Kosovo Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 7 1. Theoretical Framework ...........................................................................................12 1.1. Theories of democracy ...................................................................................... 12 1.2. Theories of democratisation ............................................................................... 22 1.2.1. Socio-cultural theoretical approach ............................................................. 25 1.2.2. System theoretical approach ....................................................................... 27 1.2.3. Structural theoretical approach .................................................................... 28 1.2.4. The actor oriented theoretical approach (Micro level) .................................. 29 1.3. Defining consolidation of democracy .................................................................. 31 1.4. Theoretical approaches in studying Political Parties.......................................... -

European Values Study 2008, 4Th Wave, Kosovo

TECHNICAL Reports 2010|17 EVS 2008 Method Report Country Report - Kosovo Documentation of the full data release 30/11/10 Related to the national dataset Archive-Study-No. ZA4790, doi:10.4232/1.10183 European Values Study and GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Acknowledgements The fieldwork of the 2008 European Values Study (EVS) was financially supported by universities and research institutes, national science foundations, charitable trusts and foundations, companies and church organizations in the EVS member countries. A major sponsor of the surveys in several Central and Eastern European countries was Renovabis. Renovabis - Solidarity initiative of the German Catholics with the people in Central and Eastern Europe: Project No. MOE016847 http://www.renovabis.de/. An overview of all national sponsors of the 2008 survey is provided in the “EVS 2008 Method Report” in section funding agency/sponsor, the “EVS 2008 Guidelines and Recommendations”, and on the web- site of the European Values Study http://www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu/evs/sponsoring.html. The project would not have been possible without the National Program Directors in the EVS member countries and their local teams. Gallup Europe developed a special questionnaire translation system WebTrans, which appeared to be very valuable and enhanced the quality of the project. Special thanks also go to the teams at Tilburg University, CEPS/INSTEAD Luxembourg, and GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Cologne. 2 GESIS-Technical Reports No. 17 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

The UN Role in Promoting Democracy: Between Ideals and Reality

United Nations University Press is the publishing arm of the United Na- tions University. UNU Press publishes scholarly and policy-oriented books and periodicals on the issues facing the United Nations and its people and member states, with particular emphasis upon international, regional, and transboundary policies. The United Nations University is an organ of the United Nations es- tablished by the General Assembly in 1972 to be an international com- munity of scholars engaged in research, advanced training, and the dis- semination of knowledge related to the pressing global problems of human survival, development, and welfare. Its activities focus mainly on the areas of peace and governance, environment and sustainable devel- opment, and science and technology in relation to human welfare. The University operates through a worldwide network of research and post- graduate training centres, with its planning and coordinating headquar- ters in Tokyo. The UN role in promoting democracy TheUNroleinpromoting democracy: Between ideals and reality Edited by Edward Newman and Roland Rich United Nations a University Press TOKYO u NEW YORK u PARIS ( United Nations University, 2004 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, 150-8925, Japan Tel: þ81-3-3499-2811 Fax: þ81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] general enquiries: [email protected] www.unu.edu United Nations University Office in North America 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2062, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: þ1-212-963-6387 Fax: þ1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. -

Kosovo's Developing Free Press

KOSOVO’S DEVELOPING FREE PRESS: HOW DO NEWSPAPERS IN A TRANSITIONING SOCIETY BEHAVE UNDER INTERNATIONAL SUPERVISION AND WHAT ROLE DO THEY PLAY DURING LOCAL ELECTIONS? A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by BESA LUCI Prof. Byron T. Scott, Thesis Supervisor AUGUST 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis titled KOSOVO’S DEVELOPING FREE PRESS: HOW DO NEWSPAPERS IN A TRANSITIONING SOCIETY BEHAVE UNDER INTERNATIONAL SUPERVISION AND WHAT ROLE DO THEY PLAY DURING LOCAL ELECTIONS? presented by Besa Luci, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ___________________________ Professor Scott T. Byron ______________________________ Professor George Kennedy _______________________________ Professor Michael J. Grinfeld _______________________ Professor Margit Tavits ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is a result of my interest in looking more thoroughly at the state of daily newspapers in Kosovo, in particular the role they play in holding the newly established Kosovar institutions accountable to a citizenry eager to establishing a democratic society. After working for several local NGO’s in Kosovo as a media monitor and acquiring an education in journalism at University of Missouri, Columbia, I was able to approach the topic with a better understanding, which was also a result of my close work with great faculty. Firstly I would like to thank my Committee Chair, Prof. Byron Scott, for his guidance and support throughout this research process. His knowledge of the region’s history and his experience with journalists from the region helped me construct my research question so that it related to my field of interest and offered me an opportunity to get thoroughly acquainted with journalistic practices in Kosovo.