Master Economics and Public Policies Master's Final Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio De Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio de Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010 Registered Attendees For The 2010 Meeting The alphabetical list below shows the final list of registered delegates for the 2010 AIB Annual Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Final Registrant Count: 895 A Esi Abbam Elliot, University of Illinois, Chicago Ashraf Abdelaal Mahmoud Abdelaal, University of Rome Tor vergata Majid Abdi, York University (Institutional Member) Monica Abreu, Universidade Federal do Ceara Kofi Afriyie, New York University Raj Aggarwal, The University of Akron Ruth V. Aguilera, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Yair Aharoni, Tel Aviv University Niklas Åkerman, Linneaus School of Business and Economics Ian Alam, State University of New York Hadi Alhorr, Saint Louis University Andreas Al-Laham, University of Mannheim Gayle Allard, IE University Helena Allman, University of South Carolina Victor Almeida, COPPEAD / UFRJ Patricia Almeida Ashley,Universidade Federal Fluminense Ilan Alon, Rollins College Marcelo Alvarado-Vargas, Florida International University Flávia Alvim, Fundação Dom Cabral Mohamed Amal, Universidade Regional de Blumenau- FURB Marcos Amatucci, Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing de SP Arash Amirkhany, Concordia University Poul Houman Andersen, Aarhus University Ulf Andersson, Copenhagen Business School Naoki Ando, Hosei University Eduardo Bom Angelo,LAZAM MDS Madan Annavarjula, Bryant University Chieko Aoki,Blue Tree Hotels Masashi Arai, Rikkyo University Camilo Arbelaez, Eafit University Harvey Arbeláez, Monterey Institute -

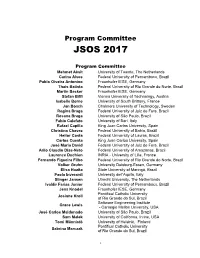

JSOS 2017 Program Committee

Program Committee JSOS 2017 Program Committee Mehmet Aksit University of Twente, The Netherlands Carina Alves Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Pablo Oiveira Antonino Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Thais Batista Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Martin Becker Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Stefan Biffl Vienna University of Technology, Austria Isabelle Borne University of South Brittany, France Jan Bosch Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden Regina Braga Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Rosana Braga University of São Paulo, Brazil Fabio Calefato University of Bari, Italy Rafael Capilla King Juan Carlos University, Spain Christina Chavez Federal University of Bahia, Brazil Heitor Costa Federal University of Lavras, Brazil Carlos Cuesta King Juan Carlos University, Spain José Maria David Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Arilo Claudio Dias-Neto Federal University of Amazonas, Brazil Laurence Duchien INRIA - University of Lille, France Fernando Figueira Filho Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Volker Gruhn University Duisburg-Essen, Germany Elisa Huzita State University of Maringá, Brazil Paola Inverardi University dell'Aquila, Italy Slinger Jansen Utrecht University, The Netherlands Ivaldir Farias Junior Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Jens Knodel Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Pontifical Catholic University Josiane Kroll of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Software Engineering Institute Grace Lewis - Carnegie Mellon University, USA José Carlos Maldonado University of São Paulo, Brazil Sam Malek -

A Framework for Threat-Driven Cyber Security Verification of Iot Systems

Conference Organizers General Chairs Edson Midorikawa (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Program Committee Chairs Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (Univ. Federal de Minas Gerais - Brazil) Steering Committee Alberto F. De Souza (UFES, Brazil) Claudio L. Amorim (UFRJ, Brazil) Edson Norberto Cáceres (UFMS, Brazil) Jairo Panetta (INPE, Brazil) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (UCI, USA) Liria M. Sato (USP, Brazil) Philippe O. A. Navaux (UFRGS, Brazil) Rajkumar Buyya Universidade de Melbourne, Australia) Siang W. Song (USP, Brazil) Viktor Prasanna (USC, USA) Vinod Rabello (UFF, Brazil) Walfredo Cirne (Google, USA) Organizing Committee Artur Baruchi (USP-Brazil) Calebe de Paula Bianchini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Denise Stringhini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Edson Toshimi Midorikawa (USP-Brazil) Francisco Isidro Massetto (USP-Brazil) Gabriel Pereira da Silva (UFRJ - Brazil) Hélio Crestana Guardia (UFSCar – Brazil) Francisco Ribacionka (USP-Brazil) Hermes Senger (UFSCar – Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (USP-Brazil) Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (UFMG - Brazil) Program Committee Alfredo Goldman vel Lejbman (USP-Brazil) Ismar Frango Silveira (Mackenzie-Brazil) Nicolas Kassalias (USJT-Brazil) x Computer Architecture Track Vice-chair: David Brooks (Harvard) Claudio L. Amorim (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) Nader Bagherzadeh (University of California at Irvine) Mauricio Breternitz Jr. (Intel) Patrick Crowley (Washington University) Cesar De Rose (PUC Rio Grande do Sul) Alberto Ferreira De Souza (Federal University of Espirito Santo) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (University of California at Irvine) Timothy Jones (University of Edinburgh) David Kaeli (Northeastern University) Jose Moreira (IBM Research) Philippe Navaux (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul) Yale Patt (University of Texas at Austin) Gabriel P. -

Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira: Representação Interinstitucional E

1 - EDITORIAL Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira Representação interinstitucional e interdisciplinar Alberto GoldenbergI, Tânia Pereira Morais FinoII Saul GoldenbergIII, I Editor Científico Acta Cir Bras II Secretaria Acta Cir Bras III Fundador e Editor Chefe Acta Cir Bras Em editorial no fascículo no 1, janeiro-fevereiro de 2009, o número de artigos do exterior e o número de suplementos no apresentou-se o desempenho da Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira referentes período. aos anos de 1986 a 20001 e de 2001 a 20052, nos quais se destacava Decidimos investigar a participação interinstitucional e a distribuição geográfica dos autores, o número de artigos nacionais, interdisciplinar da revista nos anos de 2007 e 2008. ORIGEM INSTITUCIONAL DOS ARTIGOS INSTITUIÇÕES NACIONAIS Bahia Experimental Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Bahia[UFBA] Operative Technique and Experimental Surgery, Bahia School of Medicine Brasília Laboratory of Experimental Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Brasilia, Brazil. Ceará Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará. Experimental Surgical Research Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Federal Univesity of Ceará, Brazil. Espírito Santo Laboratory Division of Surgical Principles, Department of Surgery, School of Sciences, Espirito Santo. Goiás Department of Veterinary Medicine, Veterinary Medicine College, Federal University of Goiás. Maranhão Experimental Research, Department of Surgery, Federal University of Maranhão Mato Grosso Department of Surgery,Federal University of Mato Grosso[UFMT] Mato Grosso do Sul Laboratory of Research, Mato Grosso do Sul Federal University Minas Gerais Department of Surgery, Experimental Laboratory, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais Laboratory of Apoptosis, Department of General Pathology, Institute of Biological Science, Federal University of Minas Gerais Wild Animals Research Laboratory, Federal University of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. -

Brazil Academic Webuniverse Revisited: a Cybermetric Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-LIS Brazil academic webuniverse revisited: A cybermetric analysis 1 ISIDRO F. AGUILLO 1 JOSÉ L. ORTEGA 1 BEGOÑA GRANADINO 1 CINDOC-CSIC. Joaquín Costa, 22. 28002 Madrid. Spain {isidro;jortega;bgranadino}@cindoc.csic.es Abstract The analysis of the web presence of the universities by means of cybermetric indicators has been shown as a relevant tool for evaluation purposes. The developing countries in Latin-American are making a great effort for publishing electronically their academic and scientific results. Previous studies done in 2001 about Brazilian Universities pointed out that these institutions were leaders for both the region and the Portuguese speaking community. A new data compilation done in the first months of 2006 identify an exponential increase of the size of the universities’ web domains. There is also an important increase in the web visibility of these academic sites, but clearly of much lower magnitude. After five years Brazil is still leader but it is not closing the digital divide with developed world universities. Keywords: Cybermetrics, Brazilian universities, Web indicators, Websize, Web visibility 1. Introduction. The Internet Lab (CINDOC-CSIC) has been working on the development of web indicators for the Latin-American academic sector since 1999 (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). The region is especially interesting due to the presence of several very large developing countries that are perfect targets for case studies and the use of Spanish and Portuguese languages in opposition to English usually considered the scientific “lingua franca”. -

The Pilotis As Sociospatial Integrator: the Urban Campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco

1665 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO Robson Canuto da Silva Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Maria de Lourdes da Cunha Nóbrega Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Andreyna Raphaella Sena Cordeiro de Lima Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] 8º CONGRESSO LUSO-BRASILEIRO PARA O PLANEAMENTO URBANO, REGIONAL, INTEGRADO E SUSTENTÁVEL (PLURIS 2018) Cidades e Territórios - Desenvolvimento, atratividade e novos desafios Coimbra – Portugal, 24, 25 e 26 de outubro de 2018 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO R. Canuto, M.L.C.C. Nóbrega e A. Sena ABSTRACT This study aims to investigate space configuration factors that promote patterns of pedestrian movement and social interactions on the campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco, located in Recife, in the Brazilian State of Pernambuco. The campus consists of four large urban blocks and a number of modern buildings with pilotis, whose configuration facilitates not only pedestrian movement through the urban blocks, but also various other types of activity. The methodology is based on the Social Logic of Space Theory, better known as Space Syntax. The study is structured in three parts: (1) The Urban Campus, which presents an overview of the evolution of universities and relations between campus and city; (2) Paths of an Urban Campus, which presents a spatial analysis on two scales (global and local); and (3) The Role of pilotis as a Social Integrator, which discusses the socio-spatial role of pilotis. Space Syntax techniques (axial maps of global and local integration)1 was used to shed light on the nature of pedestrian movement and its social performance. -

Formal Methods: Foundations and Applications 21St Brazilian Symposium, SBMF 2018 Salvador, Brazil, November 26–30, 2018 Proceedings

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 11254 Commenced Publication in 1973 Founding and Former Series Editors: Gerhard Goos, Juris Hartmanis, and Jan van Leeuwen Editorial Board David Hutchison Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Takeo Kanade Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Josef Kittler University of Surrey, Guildford, UK Jon M. Kleinberg Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA Friedemann Mattern ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland John C. Mitchell Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA Moni Naor Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel C. Pandu Rangan Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, India Bernhard Steffen TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany Demetri Terzopoulos University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA Doug Tygar University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Gerhard Weikum Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Saarbrücken, Germany More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7408 Tiago Massoni • Mohammad Reza Mousavi (Eds.) Formal Methods: Foundations and Applications 21st Brazilian Symposium, SBMF 2018 Salvador, Brazil, November 26–30, 2018 Proceedings 123 Editors Tiago Massoni Mohammad Reza Mousavi Federal University of Campina Grande University of Leicester Campina Grande, Brazil Leicester, UK ISSN 0302-9743 ISSN 1611-3349 (electronic) Lecture Notes in Computer Science ISBN 978-3-030-03043-8 ISBN 978-3-030-03044-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03044-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958772 LNCS Sublibrary: SL2 – Programming and Software Engineering © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Chapter “TeSSLa: Temporal Stream-Based Specification Language” is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). For further details see license information in the chapter. -

Apresentação Do Powerpoint

INTERACTION AMONG BIOGENIC, CLIMATE AND TECTONIC PROCESSES INFLUENCES TUFA PRECIPITATION, ARARIPE BASIN, BRAZIL Jaqueline Lopes Diniz1,2, Francisco Manoel Wohnrath Tognoli1,2, Tiago Siqueira de Miranda2,4, Alcides Nóbrega Sial4, Laís Vieira de Souza2, Leonardo Campos Inocencio2,3, Juliano Bonato1,2, Caroline Modica Custódio2, and Aline Fernanda Spaniol2 •1Graduate Program on Geology, Unisinos University, São Leopoldo, Brazil ([email protected]) •2VizGEO Research Group, Unisinos University, São Leopoldo, Brazil ([email protected]) •3Graduate Program on Applied Computing, Unisinos University, São Leopoldo, Brazil ([email protected]) •4Graduate Program on Geology, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil ([email protected]) Our examples include two morphotypes resulting from weathering of limestone of the Crato Formation, Araripe Basin, NE Brazil, and precipitated along vugular fractures. The presence of organic filaments and mollusk shells are recurrent in all samples. Macro and microscopic analysis revealed bryophyte filaments. Moreover, the porosity pattern strongly evidences the presence of these plants in tufa diagenesis. 9 7 5 Isotopic values measured on 32 samples indicate 3 18 13 δ O VPDB between -11,4‰ and -1,7‰ and δ C 1 VPDB between -12,1‰ and -5,1‰. The 1 4 7 10 13 16 19 22 25 28 -1 ‰ enrichment of 16O reveals the composition of -3 meteoric water, responsible by the limestone VPDB C dissolution and tufa precipitation. Organic -5 13 d fractioning induced by photosynthesis of the C4 -7 plants result in 12C enrichment in the tufas. -9 -11 -13 18 d OVSMOW ‰ Our tufas are always associated with joints and faults in the northern boundary of the basin. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

8Th IWACP Participants

Hosted by Guangdong University of Technology, Beijing Normal University, Hainan Tropical Ocean University Organized by Co-organized by Paulista University, Dongguan University of Technology, Parthenope University, University of Sheffield, Deakin University in participation with 2 8th International Workshop | Advances in Cleaner Production Technical Report Responsible for the information: Biagio F. Giannetti (Conference Chair) http://www.advancesincleanerproduction.net COUPLING GREEN AND BLUE ECONOMIES: HOW ARE CLEANER PRODUCTION AND CITIES LEADING THE NEXT SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT? Sanya, China November 13th to 15th - 2019 th 3 8 International Workshop | Advances in Cleaner Production The topic of the 8th International Workshop Advances in Cleaner Production (IWACP): Coupling green and Blue Economies: How are Cleaner Production and Cities Leading the Next Sustainable Development? was discussed by Brazilian and foreign researchers for three days in Sanya, China during the period of November 13th to 15th, 2019. The international conference was organized by the Postgraduate Program in Production Engineering (Master's and Doctoral Program) and Co-organized by Dongguan University of Technology, Parthenope University, University of Sheffield, Deakin University. The event counted with the partnership of the (University of Firenze, Italy), UNISON (Universidad de Sonora, México), the University of Manitoba (Canada), BNU (Beijing Normal University, China), the Journal of Cleaner Production, and the ACPN (Advances in Cleaner Production Network). The hosting institutions were the Guangdong University of Technology, Beijing Normal University, and Hainan Tropical Ocean University The partnership with the Journal of Cleaner Production (https://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-cleaner-production/), that started during the 1st IWACP was maintained with the support of the Co-Editors in Chief: Prof. -

Information Retrieval During Free Listing Is Biased by Memory: Evidence from Medicinal Plants

RESEARCH ARTICLE Information Retrieval during Free Listing Is Biased by Memory: Evidence from Medicinal Plants Daniel Carvalho Pires de Sousa1, Gustavo Taboada Soldati2, Julio Marcelino Monteiro3, Thiago Antonio de Sousa Arau jo4, Ulysses Paulino Albuquerque1* 1 LaboratoÂrio de Ecologia e EvolucËão de Sistemas SocioecoloÂgicos (LEA), Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Av. Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, Dois Irmãos, 52171±900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil, 2 Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Rua Jose LourencËo Kelmer, s/n, Martelos, 36036±330, Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brasil, 3 Universidade Federal do PiauõÂ, Campus UniversitaÂrio Ministro PetroÃnio Portella, s/n, Ininga, 64049±550, Teresina, PiauõÂ, Brasil, 4 LaboratoÂrio de a11111 Produtos Naturais (Lapronat), Departamento de FarmaÂcia, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Av. Professor Moraes Rego, nÊ 1235, Cidade UniversitaÂria, 50670±901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Free listing is a methodological tool that is widely used in various scientific disciplines. A Citation: Sousa DCPd, Soldati GT, Monteiro JM, typical assumption of this approach is that individual lists reflect a subset of total knowledge ArauÂjo TAdS, Albuquerque UP (2016) Information and that the first items listed are the most culturally important. However, little is known Retrieval during Free Listing Is Biased by Memory: Evidence from Medicinal Plants. PLoS ONE 11(11): about how cognitive processes influence free lists. In this study, we assess how recent e0165838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165838 memory of use, autonoetic and anoetic memory, and long-term associative memory can Editor: Neil R. Smalheiser, University of Illinois- affect the composition and order of items in free lists and evaluate whether free lists indi- Chicago, UNITED STATES cate the most important items. -

How Do We Want to Live Tomorrow? Perspectives on Water Management in Urban Regions Imprint

SCIENCE POLICY REPORT • JUNE 2017 How Do We Want to Live Tomorrow? Perspectives on Water Management in Urban Regions Imprint Publishers Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e.V. Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Jägerberg 1 06108 Halle (Saale), Germany Academia Brasileira de Ciências (ABC) Brazilian Academy of Sciences Rua Anfilófio de Carvalho, 29, 3° andar Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Zentrum für Wasser- und Umweltforschung (ZWU) Universität Duisburg-Essen Centre for Water and Environmental Research Universitätsstraße 2 45141 Essen, Germany Design unicommunication, Berlin Print druckhaus köthen GmbH & Co. KG Friedrichstr. 11/12 06366 Köthen (Anhalt) Germany Editing Dr. Jan Nissen, Leopoldina Francesca Azara, Leopoldina Marcos Cortesão Barnsley Scheuenstuhl, ABC Dr. Michael Eisinger, ZWU ISBN: 978-3-8047-3746-4 Title Picture View of Recife – Photo by Juliana Costa Photography SCIENCE POLICY REPORT • JUNE 2017 How Do We Want to Live Tomorrow? Perspectives on Water Management in Urban Regions Viktoria Berger Rodrigo Lilla Manzione Benedikt Roters Fernando Mainardi Fan Elena Matta Stephan Schulz Friederike Gabel Ana Andreu Mendez Talita Fernanda das Graças Silva Paulo Henrique Galvão Marcio Augusto Ernesto de Moraes Matheus Martins de Sousa Maria Gies Ana Carolina Daniel Morihama Alexandra Suhogusoff Daniel Grabner Anderson Luiz Ribeiro de Paiva Ingo Daniel Wahnfried Simone Langhans Natalia Andricioli Periotto Christine Wolf Priscilla Macedo-Moura Gwendolin Porst Anderson Abel de Souza Machado Caroline Rigotto 2 | HOW DO WE WANT TO LIVE TOMORROW? • TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Foreword 3 Executive Summary 4 Integrated Watershed Management for Urban Areas 5 Sustainable Sanitation and Rainwater Management 8 Micropollutants 11 Information Flow and People’s Involvement 15 References 19 Authors 23 FOREWORD • HOW DO WE WANT TO LIVE TOMORROW? | 3 Foreword The sustainable use of water resources in urban regions is essential in order to ensure a livable environment for future generations.