The Ongoing Evolution of Variants of Concern and Interest of SARS-Cov-2 in Brazil Revealed by Convergent Indels in the Amino (N)-Terminal Domain of the Spike Protein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio De Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio de Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010 Registered Attendees For The 2010 Meeting The alphabetical list below shows the final list of registered delegates for the 2010 AIB Annual Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Final Registrant Count: 895 A Esi Abbam Elliot, University of Illinois, Chicago Ashraf Abdelaal Mahmoud Abdelaal, University of Rome Tor vergata Majid Abdi, York University (Institutional Member) Monica Abreu, Universidade Federal do Ceara Kofi Afriyie, New York University Raj Aggarwal, The University of Akron Ruth V. Aguilera, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Yair Aharoni, Tel Aviv University Niklas Åkerman, Linneaus School of Business and Economics Ian Alam, State University of New York Hadi Alhorr, Saint Louis University Andreas Al-Laham, University of Mannheim Gayle Allard, IE University Helena Allman, University of South Carolina Victor Almeida, COPPEAD / UFRJ Patricia Almeida Ashley,Universidade Federal Fluminense Ilan Alon, Rollins College Marcelo Alvarado-Vargas, Florida International University Flávia Alvim, Fundação Dom Cabral Mohamed Amal, Universidade Regional de Blumenau- FURB Marcos Amatucci, Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing de SP Arash Amirkhany, Concordia University Poul Houman Andersen, Aarhus University Ulf Andersson, Copenhagen Business School Naoki Ando, Hosei University Eduardo Bom Angelo,LAZAM MDS Madan Annavarjula, Bryant University Chieko Aoki,Blue Tree Hotels Masashi Arai, Rikkyo University Camilo Arbelaez, Eafit University Harvey Arbeláez, Monterey Institute -

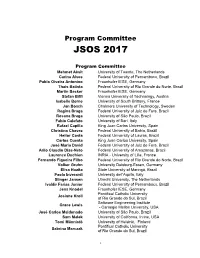

JSOS 2017 Program Committee

Program Committee JSOS 2017 Program Committee Mehmet Aksit University of Twente, The Netherlands Carina Alves Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Pablo Oiveira Antonino Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Thais Batista Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Martin Becker Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Stefan Biffl Vienna University of Technology, Austria Isabelle Borne University of South Brittany, France Jan Bosch Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden Regina Braga Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Rosana Braga University of São Paulo, Brazil Fabio Calefato University of Bari, Italy Rafael Capilla King Juan Carlos University, Spain Christina Chavez Federal University of Bahia, Brazil Heitor Costa Federal University of Lavras, Brazil Carlos Cuesta King Juan Carlos University, Spain José Maria David Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Arilo Claudio Dias-Neto Federal University of Amazonas, Brazil Laurence Duchien INRIA - University of Lille, France Fernando Figueira Filho Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Volker Gruhn University Duisburg-Essen, Germany Elisa Huzita State University of Maringá, Brazil Paola Inverardi University dell'Aquila, Italy Slinger Jansen Utrecht University, The Netherlands Ivaldir Farias Junior Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Jens Knodel Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Pontifical Catholic University Josiane Kroll of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Software Engineering Institute Grace Lewis - Carnegie Mellon University, USA José Carlos Maldonado University of São Paulo, Brazil Sam Malek -

A Framework for Threat-Driven Cyber Security Verification of Iot Systems

Conference Organizers General Chairs Edson Midorikawa (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Program Committee Chairs Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (Univ. Federal de Minas Gerais - Brazil) Steering Committee Alberto F. De Souza (UFES, Brazil) Claudio L. Amorim (UFRJ, Brazil) Edson Norberto Cáceres (UFMS, Brazil) Jairo Panetta (INPE, Brazil) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (UCI, USA) Liria M. Sato (USP, Brazil) Philippe O. A. Navaux (UFRGS, Brazil) Rajkumar Buyya Universidade de Melbourne, Australia) Siang W. Song (USP, Brazil) Viktor Prasanna (USC, USA) Vinod Rabello (UFF, Brazil) Walfredo Cirne (Google, USA) Organizing Committee Artur Baruchi (USP-Brazil) Calebe de Paula Bianchini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Denise Stringhini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Edson Toshimi Midorikawa (USP-Brazil) Francisco Isidro Massetto (USP-Brazil) Gabriel Pereira da Silva (UFRJ - Brazil) Hélio Crestana Guardia (UFSCar – Brazil) Francisco Ribacionka (USP-Brazil) Hermes Senger (UFSCar – Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (USP-Brazil) Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (UFMG - Brazil) Program Committee Alfredo Goldman vel Lejbman (USP-Brazil) Ismar Frango Silveira (Mackenzie-Brazil) Nicolas Kassalias (USJT-Brazil) x Computer Architecture Track Vice-chair: David Brooks (Harvard) Claudio L. Amorim (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) Nader Bagherzadeh (University of California at Irvine) Mauricio Breternitz Jr. (Intel) Patrick Crowley (Washington University) Cesar De Rose (PUC Rio Grande do Sul) Alberto Ferreira De Souza (Federal University of Espirito Santo) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (University of California at Irvine) Timothy Jones (University of Edinburgh) David Kaeli (Northeastern University) Jose Moreira (IBM Research) Philippe Navaux (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul) Yale Patt (University of Texas at Austin) Gabriel P. -

Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira: Representação Interinstitucional E

1 - EDITORIAL Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira Representação interinstitucional e interdisciplinar Alberto GoldenbergI, Tânia Pereira Morais FinoII Saul GoldenbergIII, I Editor Científico Acta Cir Bras II Secretaria Acta Cir Bras III Fundador e Editor Chefe Acta Cir Bras Em editorial no fascículo no 1, janeiro-fevereiro de 2009, o número de artigos do exterior e o número de suplementos no apresentou-se o desempenho da Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira referentes período. aos anos de 1986 a 20001 e de 2001 a 20052, nos quais se destacava Decidimos investigar a participação interinstitucional e a distribuição geográfica dos autores, o número de artigos nacionais, interdisciplinar da revista nos anos de 2007 e 2008. ORIGEM INSTITUCIONAL DOS ARTIGOS INSTITUIÇÕES NACIONAIS Bahia Experimental Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Bahia[UFBA] Operative Technique and Experimental Surgery, Bahia School of Medicine Brasília Laboratory of Experimental Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Brasilia, Brazil. Ceará Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará. Experimental Surgical Research Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Federal Univesity of Ceará, Brazil. Espírito Santo Laboratory Division of Surgical Principles, Department of Surgery, School of Sciences, Espirito Santo. Goiás Department of Veterinary Medicine, Veterinary Medicine College, Federal University of Goiás. Maranhão Experimental Research, Department of Surgery, Federal University of Maranhão Mato Grosso Department of Surgery,Federal University of Mato Grosso[UFMT] Mato Grosso do Sul Laboratory of Research, Mato Grosso do Sul Federal University Minas Gerais Department of Surgery, Experimental Laboratory, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais Laboratory of Apoptosis, Department of General Pathology, Institute of Biological Science, Federal University of Minas Gerais Wild Animals Research Laboratory, Federal University of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. -

Multiple Recombination Events and Strong Purifying Selection at the Origin of SARS-Cov-2 Spike Glycoprotein Increased Correlated Dynamic Movements

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Multiple Recombination Events and Strong Purifying Selection at the Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Increased Correlated Dynamic Movements Massimiliano S. Tagliamonte 1,2,† , Nabil Abid 3,4,†, Stefano Borocci 5,6 , Elisa Sangiovanni 5, David A. Ostrov 2 , Sergei L. Kosakovsky Pond 7, Marco Salemi 1,2,*, Giovanni Chillemi 5,8,*,‡ and Carla Mavian 1,2,*,‡ 1 Emerging Pathogen Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32608, USA; mstagliamonte@ufl.edu 2 Department of Pathology, Immunology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA; [email protected]fl.edu 3 Laboratory of Transmissible Diseases and Biological Active Substances LR99ES27, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Monastir, Rue Ibn Sina, 5000 Monastir, Tunisia; [email protected] 4 Department of Biotechnology, High Institute of Biotechnology of Sidi Thabet, University of Manouba, BP-66, 2020 Ariana-Tunis, Tunisia 5 Department for Innovation in Biological, Agro-food and Forest Systems (DIBAF), University of Tuscia, via S. Camillo de Lellis s.n.c., 01100 Viterbo, Italy; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (E.S.) 6 Institute for Biological Systems, National Research Council, Via Salaria, Km 29.500, 00015 Monterotondo, Rome, Italy 7 Department of Biology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA; [email protected] 8 Institute of Biomembranes, Bioenergetics and Molecular Biotechnologies (IBIOM), National Research Council, Via Giovanni Amendola, 122/O, 70126 Bari, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]fl.edu (M.S.); [email protected] (G.C.); cmavian@ufl.edu (C.M.) † Authors contributed equally as first to this work. ‡ Authors contributed equally as last to this work. -

Brazil Academic Webuniverse Revisited: a Cybermetric Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-LIS Brazil academic webuniverse revisited: A cybermetric analysis 1 ISIDRO F. AGUILLO 1 JOSÉ L. ORTEGA 1 BEGOÑA GRANADINO 1 CINDOC-CSIC. Joaquín Costa, 22. 28002 Madrid. Spain {isidro;jortega;bgranadino}@cindoc.csic.es Abstract The analysis of the web presence of the universities by means of cybermetric indicators has been shown as a relevant tool for evaluation purposes. The developing countries in Latin-American are making a great effort for publishing electronically their academic and scientific results. Previous studies done in 2001 about Brazilian Universities pointed out that these institutions were leaders for both the region and the Portuguese speaking community. A new data compilation done in the first months of 2006 identify an exponential increase of the size of the universities’ web domains. There is also an important increase in the web visibility of these academic sites, but clearly of much lower magnitude. After five years Brazil is still leader but it is not closing the digital divide with developed world universities. Keywords: Cybermetrics, Brazilian universities, Web indicators, Websize, Web visibility 1. Introduction. The Internet Lab (CINDOC-CSIC) has been working on the development of web indicators for the Latin-American academic sector since 1999 (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). The region is especially interesting due to the presence of several very large developing countries that are perfect targets for case studies and the use of Spanish and Portuguese languages in opposition to English usually considered the scientific “lingua franca”. -

The Pilotis As Sociospatial Integrator: the Urban Campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco

1665 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO Robson Canuto da Silva Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Maria de Lourdes da Cunha Nóbrega Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Andreyna Raphaella Sena Cordeiro de Lima Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] 8º CONGRESSO LUSO-BRASILEIRO PARA O PLANEAMENTO URBANO, REGIONAL, INTEGRADO E SUSTENTÁVEL (PLURIS 2018) Cidades e Territórios - Desenvolvimento, atratividade e novos desafios Coimbra – Portugal, 24, 25 e 26 de outubro de 2018 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO R. Canuto, M.L.C.C. Nóbrega e A. Sena ABSTRACT This study aims to investigate space configuration factors that promote patterns of pedestrian movement and social interactions on the campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco, located in Recife, in the Brazilian State of Pernambuco. The campus consists of four large urban blocks and a number of modern buildings with pilotis, whose configuration facilitates not only pedestrian movement through the urban blocks, but also various other types of activity. The methodology is based on the Social Logic of Space Theory, better known as Space Syntax. The study is structured in three parts: (1) The Urban Campus, which presents an overview of the evolution of universities and relations between campus and city; (2) Paths of an Urban Campus, which presents a spatial analysis on two scales (global and local); and (3) The Role of pilotis as a Social Integrator, which discusses the socio-spatial role of pilotis. Space Syntax techniques (axial maps of global and local integration)1 was used to shed light on the nature of pedestrian movement and its social performance. -

Inverted Repeats in Coronavirus SARS-Cov-2 Genome and Implications in Evolution

Inverted repeats in coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 genome and implications in evolution Changchuan Yin ID ∗ Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL 60607 USA Stephen S.-T. Yau ID y Department of Mathematical Sciences Tsinghua University Beijing 100084 China Abstract The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the coronavirus SARS- CoV-2, has caused 60 millions of infections and 1.38 millions of fatalities. Genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 can provide insights on drug design and vaccine develop- ment for controlling the pandemic. Inverted repeats in a genome greatly impact the stability of the genome structure and regulate gene expression. Inverted repeats involve cellular evolution and genetic diversity, genome arrangements, and diseases. Here, we investigate the inverted repeats in the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 genome. We found that SARS-CoV-2 genome has an abundance of inverted repeats. The inverted repeats are mainly located in the gene of the Spike protein. This result suggests the Spike protein gene undergoes recombination events, therefore, is essential for fast evolution. Comparison of the inverted repeat signatures in human and bat coronaviruses suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is mostly related SARS-related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV/RaTG13. The study also reveals that the recent SARS- related coronavirus, SARSr-CoV/RmYN02, has a high amount of inverted repeats in the spike protein gene. Besides, this study demonstrates that the inverted repeat distribution in a genome can be considered as the genomic signature. This study highlights the significance of inverted repeats in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and presents the inverted repeats as the genomic signature in genome analysis. -

Exploring the Natural Origins of SARS-Cov-2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427830; this version posted January 22, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Exploring the natural origins of SARS-CoV-2 1 1 2 3 1,* Spyros Lytras , Joseph Hughes , Wei Xia , Xiaowei Jiang , David L Robertson 1 MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR), Glasgow, UK. 2 National School of Agricultural Institution and Development, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), Suzhou, China. * Correspondence: [email protected] Summary. The lack of an identifiable intermediate host species for the proximal animal ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 and the distance (~1500 km) from Wuhan to Yunnan province, where the closest evolutionary related coronaviruses circulating in horseshoe bats have been identified, is fueling speculation on the natural origins of SARS-CoV-2. Here we analyse SARS-CoV-2’s related horseshoe bat and pangolin Sarbecoviruses and confirm Rhinolophus affinis continues to be the likely reservoir species as its host range extends across Central and Southern China. This would explain the bat Sarbecovirus recombinants in the West and East China, trafficked pangolin infections and bat Sarbecovirus recombinants linked to Southern China. Recent ecological disturbances as a result of changes in meat consumption could then explain SARS-CoV-2 transmission to humans through direct or indirect contact with the reservoir wildlife, and subsequent emergence towards Hubei in Central China. -

WHO-Convened Global Study of Origins of SARS-Cov-2: China Part

WHO-convened Global Study of Origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part Joint WHO-China Study 14 January-10 February 2021 Joint Report 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARI acute respiratory illness cDNA complementary DNA China CDC Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention CNCB China National Center for Bioinformation CoV coronavirus Ct values cycle threshold values DDBJ DNA Database of Japan EMBL-EBI European Molecular Biology Laboratory and European Bioinformatics Institute FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GISAID Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Database GOARN Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network Hong Kong SAR Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Huanan market Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market IHR International Health Regulations (2005) ILI influenza-like illness INSD International Nucleotide Sequence Database MERS Middle East respiratory syndrome MRCA most recent common ancestor NAT nucleic acid testing NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information NMDC National Microbiology Data Center NNDRS National Notifiable Disease Reporting System OIE World Organisation for Animal Health (Office international des Epizooties) PCR polymerase chain reaction PHEIC public health emergency of international concern RT-PCR real-time polymerase chain reaction SARI severe acute respiratory illness SARS-CoV-2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 SARSr-CoV-2 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-related virus tMRCA time to most recent common ancestor WHO World Health Organization WIV Wuhan Institute of Virology 2 Acknowledgements WHO gratefully acknowledges the work of the joint team, including Chinese and international scientists and WHO experts who worked on the technical sections of this report, and those who worked on studies to prepare data and information for the joint mission. -

Science Journals

RESEARCH CORONAVIRUS ticles showed enhanced heterologous binding and neutralization properties against hu- Mosaic nanoparticles elicit cross-reactive immune man and bat SARS-like betacoronaviruses (sarbecoviruses). responses to zoonotic coronaviruses in mice We used a study of sarbecovirus RBD re- ceptor usage and cell tropism (38) to guide Alexander A. Cohen1, Priyanthi N. P. Gnanapragasam1, Yu E. Lee1, Pauline R. Hoffman1, Susan Ou1, our choice of RBDs for co-display on mosaic Leesa M. Kakutani1, Jennifer R. Keeffe1, Hung-Jen Wu2, Mark Howarth2, Anthony P. West1, particles. From 29 RBDs that were classified Christopher O. Barnes1, Michel C. Nussenzweig3, Pamela J. Bjorkman1* into distinct clades (clades 1, 2, 1/2, and 3) (38), we identified diverse RBDs from SARS- Protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and SARS-related emergent CoV, WIV1, and SHC014 (clade 1); SARS-CoV-2 zoonotic coronaviruses is urgently needed. We made homotypic nanoparticles displaying the receptor binding (clade 1/2); Rs4081, Yunnan 2011 (Yun11), and domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 or co-displaying SARS-CoV-2 RBD along with RBDs from animal betacoronaviruses Rf1 (clade 2); and BM-4831 (clade 3). Of these, that represent threats to humans (mosaic nanoparticles with four to eight distinct RBDs). Mice immunized SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV are human coro- with RBD nanoparticles, but not soluble antigen, elicited cross-reactive binding and neutralization responses. naviruses and the rest are bat viruses originat- Mosaic RBD nanoparticles elicited antibodies with superior cross-reactive recognition of heterologous RBDs ing in China or Bulgaria (BM-4831). We also relative to sera from immunizations with homotypic SARS-CoV-2–RBD nanoparticles or COVID-19 convalescent included RBDs from the GX pangolin clade 1/2 human plasmas. -

The SARS-Cov-2 Arginine Dimers

The SARS-CoV-2 arginine dimers Antonio R. Romeu ( [email protected] ) University Rovira i Virgili Enric Ollé University Rovira i Virgili Short Report Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Sarbecovirus, Arginine dimer, Arginine codons usage, Bioinformatics Posted Date: August 2nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-770380/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License The SARS-CoV-2 arginine dimers Antonio R. Romeu1 and Enric Ollé2 1: Chemist. Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. University Rovira i Virgili. Tarragona. Spain. Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 2: Veterinarian, Biochemist. Associate Professor of the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology. University Rovira i Virgili. Tarragona. Spain. Email: [email protected] Abstract Arginine is present, even as a dimer, in the viral polybasic furin cleavage sites, including that of SARS-CoV-2 in its protein S, whose acquisition is one of its characteristics that distinguishes it from the rest of the sarbecoviruses. The CGGCGG sequence encodes the SARS-CoV-2 furin site RR dimer. The aim of this work is to report the other SARS-CoV-2 arginine pairs, with particular emphasis in their codon usage. Here we show the presence of RR dimers in the orf1ab related non structural proteins nsp3, nsp4, nsp6, nsp13 and nsp14A2. Also, with a higher proportion in the structural roteinp nucleocapsid. All these RR dimers were strictly conserved in the sarbecovirus strains closest to SARS-CoV-2, and none of them was encoded by the CGGCGG sequence. Key words SARS-CoV-2, Sarbecovirus, Arginine dimer, Arginine codons usage, Bioinformatics Introduction Arginine (R) is a polar and non-hydrophobic amino acid, with a positive charged guanidine group, a physiological pH, linked a 3-hydrocarbon aliphatic chain.