China's Competition Policy Reforms: the Anti-Monopoly Law and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part I: Introduction

Part I: Introduction “Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.” -Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1776) “For my part, whatever anguish of spirit it may cost, I am willing to know the whole truth; to know the worst and provide for it.” -Patrick Henry (1776) “I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth. On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen -- but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead.” -William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (1831) “Gas is running low . .” -Amelia Earhart (July 2, 1937) 1 2 Dear Reader, Civilization as we know it is coming to an end soon. This is not the wacky proclamation of a doomsday cult, apocalypse bible prophecy sect, or conspiracy theory society. -

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game in 1934, Charles B

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game In 1934, Charles B. Darrow of Germantown, Pennsylvania, presented a game called MONOPOLY to the executives of Parker Brothers. Mr. Darrow, like many other Americans, was unemployed at the time and often played this game to amuse himself and pass the time. It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune that initially prompted Darrow to produce this game on his own. With help from a friend who was a printer, Darrow sold 5,000 sets of the MONOPOLY game to a Philadelphia department store. As the demand for the game grew, Darrow could not keep up with the orders and arranged for Parker Brothers to take over the game. Since 1935, when Parker Brothers acquired the rights to the game, it has become the leading proprietary game not only in the United States but throughout the Western World. As of 1994, the game is published under license in 43 countries, and in 26 languages; in addition, the U.S. Spanish edition is sold in another 11 countries. OBJECT…The object of the game is to become the wealthiest player through buying, renting and selling property. EQUIPMENT…The equipment consists of a board, 2 dice, tokens, 32 houses and 12 hotels. There are Chance and Community Chest cards, a Title Deed card for each property and play money. PREPARATION…Place the board on a table and put the Chance and Community Chest cards face down on their allotted spaces on the board. Each player chooses one token to represent him/her while traveling around the board. -

Anti-Monopoly Law

October 2002 China’s Draft Anti-Monopoly Law Paul, Weiss has recently obtained a draft of the Anti-Monopoly Law (the "AML") of the People's Republic of China ("PRC" or "China") dated February 26, 2002. We attach for your information the Paul, Weiss translation of the draft AML, and provide in this memorandum an initial analysis of the draft AML and other PRC statutes related to anti-monopoly review and regulation. The current draft is apparently not the final version, but as the AML has been in the drafting process since 1994, we believe it represents something close to the principles that will be reflected in the legislation if and when it is finally adopted. I. Outline of the AML A. General The AML governs three types of activities: (a) "activities restricting competition in market transactions" within China, (b) the "abuse of administrative powers to restrict competition" within China, and (c) activities outside China that violate the AML and that restrict or affect competition within China.1 In general, it regulates the activities of "operators," defined in Article 4 to mean legal persons and other organizations and individuals engaged in the production and operation of commodities or services. Article 4 further states that the term "commodities" under the AML includes services. Finally, "market" for purposes of the AML means a geographical area within which operators compete with respect to a given commodity over a certain period of time.2 A key element of the AML is its provision in Chapter 6 for the establishment of a new government agency charged with enforcement. -

MONOPOLY EXPRESS INSTRUCTIONS F MONOPOLY 101 Hasbro Design Centre (STU) Design Centre Hasbro

ITEM CODE First 42787 Artwork Originator: Hasbro Design Centre (STU) File Name: Express Instructions 101 Line Year: 2005 APPLY Artwork Start: 19.05.05 APPROVAL Product: Monopoly Express LID BASE CARTON GAMEBOARD RULES NOTE Repro Start: 00.05.05 Instructions CARDS DIECUT SHEET DECALS HERE! Calcul de vos gains 5. Si vous avez obtenu un hôtel, à Astuce Si vous aimez les jeux de dés, tentez Lorsque vous décidez d'arrêter les lancers de dés, condition d’avoir déjà 4 maisons, Plus les propriétés sont chères, plus elles sont rares. votre chance en jouant à Yahtzee ! € additionnez vos gains durant ce tour : vous avez touché 5 000 . Sur chaque dé propriété figurent plusieurs propriétés alors réfléchissez-bien avant de le placer sur le plateau, car il pourrait vous manquer lorsque 1. Pour chaque groupe de couleur complet sur N’oubliez pas, vous perdez tout l’argent gagné vous aurez besoin de compléter d'autres groupes. le plateau, additionnez les montants indiqués durant ce tour, si vous avez rempli les 3 cases sur le plateau. Allez en prison. express Gares, services publics et groupes de 2. Si vous avez des groupes incomplets lorsque Passez alors la piste de lancer au joueur suivant, couleur à collecter : vous décidez d’arrêter votre tour, choisissez le remettez les maisons au centre si vous en avez, et groupe de la plus grande valeur et additionnez retirez tous les dés du plateau. = 2 500 = 1 800 la valeur de chaque dé à votre total. Vous n’avez droit qu’à un seul groupe incomplet. Victoire = 800 = 2 200 Le premier joueur qui empoche une fortune de = 600 = 2 700 3. -

42749 Rules Monopoly

HOTELS If you owe the Bank more than you can pay, even by selling off buildings and mortgaging property, You must have four houses on each property of a you must turn over all assets to the Bank. The Bank complete color-group before you can buy a hotel. You will immediately auction all property so taken, may then buy a hotel from the Bank to be built on any except buildings. property of that color-group. Remove your token from the board once bankruptcy To build a hotel, you must ask the Bank to exchange the proceedings are completed. four houses on the chosen property for a hotel as well as make the payment printed on the Title Deed. WINNING It can be very advantageous to build hotels because very The last player remaining in the game wins. large rents are charged for them. ONLY ONE HOTEL MAY BE BUILT ON ANY ONE ABRIDGED VERSIONS OF THE GAME PROPERTY. Short Game (60 to 90 Minutes) SELLING PROPERTY There are five changed rules for this version of the game: ® Undeveloped properties, railroads and utilities (but 1. During PREPARATION, the Banker shuffles then not buildings) may be sold to any player as a private deals three Title Deed cards to each player. These transaction for a sum agreeable to the owner. No property, BRAND are free – no payment to the Bank is required. Property Trading Game from Parker Brothers ® however, may be sold to another player if any buildings 2. You need only three houses (instead of four) on each stand on any property of that color-group. -

Monopoly: a Game of Strategy…Or Luck? EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Serene Li Hui Heng , Xiaojun Jiang , Cheewei Ng, Li Xue Alison Then Team 5, MS&E220 Autumn 2008

Monopoly: A Game of Strategy…Or Luck? EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Serene Li Hui Heng , Xiaojun Jiang , Cheewei Ng, Li Xue Alison Then Team 5, MS&E220 Autumn 2008 A popular board game since 1935, Monopoly is a game that may be dependent on both luck and strategy. A player can bet on his or her own luck alone, think carefully and buy up strategic properties, or use strategy to complement his or her luck to gain dominance in the game. Our report seeks to present our findings on the importance of strategy in Monopoly, as well as which strategies are the most successful. So is Monopoly a game of strategy, or luck, or both? Our methodology involved examining the inter-relationships between the various factors in the game, for example, the throw of the 2 dice, the number of throws that a player has played, the number of rounds he is in, accounting for jail and rent etc. After establishing the inter-relations, we built up our model by gradually adding more factors (which increase uncertainty) that affect the game, and thereby incorporated more realism into the model. We thus proceeded to build 3 main models, by using dynamic equations. First we used the propagation of probability flow method to determine the chances of landing on a particular square in a given number of throws (Model 1). Next, we included regeneration points in the case where jail is considered (Model 2). Lastly, from the probability flow sequences obtained, we calculated the expected value of landing on each square on the board, taking into account the rents paid and $200 that a player gets each time after he passes a round, to analyze the wealth effect when multiple players are involved (Model 3). -

Using Monopoly to Introduce Concepts of Race and Ethnic Relations

The Journal of Effective Teaching an online journal devoted to teaching excellence Using Monopoly to Introduce Concepts of Race and Ethnic Relations Warren Waren1 University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL 32816-1360 Abstract In this paper I suggest a technique which uses the familiar Parker Brother’s game Mo- nopoly to introduce core concepts of race and ethnic relations. I offer anecdotes from my classes where an abbreviated version of the game is used as an analog to highlight the so- ciological concepts of direct institutional discrimination, the legacy of discrimination, co- lorblind racism, affirmative action, and reparations. I describe how, after playing the game, the participants spend a short amount of time debriefing in order to express their emotions and examine their motivations. Later, in a broader class discussion, I invite both participants and observers to explain the motivations, attitudes, and behaviors of all play- ers and connect these explanations to theoretical concepts in sociology. After debriefing and discussion, I refer to the shared experiences of the students from the game in subse- quent lectures and readings. Keywords: Teaching race, simulation, monopoly, symbolic racism, colorblind ra- cism. Undergraduate students often enter our classrooms convinced that the battles of the Civil Rights Era solved the issue of race in America. They are generally unacquainted with the long history of race in the United States and almost universally underestimate the struc- tural forces which carry racial disparities into their new century. As sociologists and teachers, it is our responsibility to tell that story and explain those forces. Our new chal- lenge is: How do we teach students the extent of racism in America when, from their point of view, the problem of the color-line has been solved? One option is to use a game. -

Monopoly Quick Guide

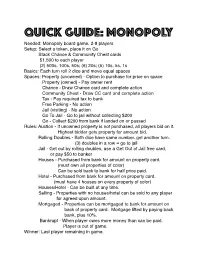

QUICK GUIDE: MONOPOLY Needed: Monopoly board game, 2-8 players Setup: Select a token, place it on Go Stack Chance & Community Chest cards $1,500 to each player (2) 500s, 100s, 50s; (6) 20s; (5) 10s, 5s, 1s Basics: Each turn roll 2 dice and move equal spaces Spaces: Property (unowned) - Option to purchase for price on space Property (owned) - Pay owner rent Chance - Draw Chance card and complete action Community Chest - Draw CC card and complete action Tax - Pay required tax to bank Free Parking - No action Jail (visiting) - No action Go To Jail - Go to jail without collecting $200 Go - Collect $200 from bank if landed on or passed Rules: Auction - If unowned property is not purchased, all players bid on it. Highest bidder gets property for amount bid. Rolling Doubles - Both dice have same number, get another turn. (3) doubles in a row = go to jail Jail - Get out by rolling doubles, use a Get Out of Jail free card, or pay $50 to banker Houses - Purchased from bank for amount on property card. (must own all properties of color) Can be sold back to bank for half price paid. Hotel - Purchased from bank for amount on property card. (must have 4 houses on every property of color) Houses/Hotel - Can be built at any time. Selling - Properties with no houses/hotel can be sold to any player for agreed upon amount. Mortgaged - Properties can be mortgaged to bank for amount on back of property card. Mortgage lifted by paying back bank, plus 10%. Bankrupt - When player owes more money than can be paid. -

ATP 2104 – Transcript 100220

The University of Detroit mercy presents another brand new episode of Ask The professor. Today's program was recorded using zoom video conferencing technology. The university tower chimes ring in another session of Ask The professor, the show on which you match wits with the University of Detroit Mercy professors in an unrehearsed session of questions and answers. I'm your host Matt Mio, and let me introduce to you our panel for today. To my left ish. It's Professor Dave Chow. Pleasure to be here as always. Excellent. So how's the basement over there Dave? is it dry. So far so good. I mean, no flooding yet. Hopefully it won't. I've got way more stuff than the last flood so I don't want to deal with it. It's wild, absolutely wild. It is. Professor Jim Tubbs is here. Hello Hello, how are you. How's it going, Jim? Good I don't have a basement that’s flooded cuz I don't have a basement. So, that is, you were in the catbird seat. Like literally man. I wouldn’t say that. usually I want a basement. I want all that place to just throw stuff, you know, Except for on days like this. I think the final count from the NOAA was four plus inches in a very short period of time. Wow. Professor Beth Oljar is here and she's on her brand new computer, But still being challenged by technology. Somehow or other, it was the privacy settings that were preventing the microphone. -

Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Sid Sackson Collection Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003 Summary Information Title: Sid Sackson collection Creator: Sid Sackson (primary) ID: 2016.sackson Date: 1867-2003 (inclusive); 1960-1995 (bulk) Extent: 36 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English. There are some instances of additional languages, including German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish; these are denoted in the Contents List section of this finding aid. Abstract: The Sid Sackson collection is a compilation of diaries, correspondence, notes, game descriptions, and publications created or used by Sid Sackson during his lengthy career in the toy and game industry. The bulk of the materials are from between 1960 and 1995. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Intellectual property rights to the donated materials are held by the Sackson heirs or assignees. Anyone who would like to develop and publish a game using the ideas found in the papers should contact Ms. Dale Friedman (624 Birch Avenue, River Vale, New Jersey, 07675) for permission. Custodial History: The Strong received the Sid Sackson collection in three separate donations: the first (Object ID 106.604) from Dale Friedman, Sid Sackson’s daughter, in May 2006; the second (Object ID 106.1637) from the Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors (AGPC) in August 2006; and the third (Object ID 115.2647) from Phil and Dale Friedman in October 2015. -

Addendum Monopoly™ Millionaires' Club™ Tv Game

EFFECTIVE: October 19, 2014 ADDENDUM MONOPOLY™ MILLIONAIRES’ CLUB™ TV GAME SHOW (5 out of 52 & 1 out of 28) The following rules have been adopted by the New Jersey State Lottery Commission pursuant to the authorization contained in N.J.S.A. 5:9-7 and shall govern the operation of the “MONOPOLY™ MILLIONAIRES’ CLUB™” lottery game. Unless otherwise defined or the context clearly indicates otherwise, all capitalized terms used in this Addendum shall have the same meaning as defined in the Official Game Rules. The additional rules are as follows: 1. DEFINITIONS Account Holder – means a Purchaser of a Monopoly Millionaires’ Club ticket who, consistent with the rules outlined in this Addendum, has validly registered for an online account on the Website. The Account Holder must be at least eighteen (18) years of age. Bonus Qualifying Property - means a MONOPOLY game board property that is assigned to an Account Holder at random upon each entry of a valid Webcode on the Website by the Account Holder. Community Chest Card – means the MONOPOLY game element awarded to an Account Holder at initial registration that represents a completed MONOPOLY Property Group selected at random. The Account Holder is automatically entitled to the number of Entries the MONOPOLY Property Group represents, as outlined on Table 1. Entry or Entries – A registered chance for a selection to participate as a studio audience member on the TV Show. An Account Holder receives Entries by entering Webcodes into the Website. The number of Entries allocated to the Account Holder depends on the specific MONOPOLY Property Group, as outlined in Table 1, that the Account Holder has collected and submitted to his online account. -

Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529018f2 No online items Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Processed by Stephan Potchatek; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Special Collections M0997 1 Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: M0997 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Stephan Potchatek Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Date (inclusive): ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: Special Collections M0997 Creator: Cabrinety, Stephen M. Extent: 815.5 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Access restricted; this collection is stored off-site in commercial storage from which material is not routinely paged. Access to the collection will remain restricted until such time as the collection can be moved to Stanford-owned facilities. Any exemption from this rule requires the written permission of the Head of Special Collections.