Indiana Moral Mondays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Higher Ground Moral Declaration

HIGHER GROUND MORAL DECLARATION It is time to move beyond left and right, liberal and conservative, and uphold higher ground moral values! Call to Action for a Moral Agenda On April 4, 1967, just one year before his assassination, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., called for a time to break the silence about the injustices in society. At the historic Riverside Church, he preached, “we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values.” He proclaimed that silence was betrayal – the truth must be told. Rev. Dr. King’s charge for a revolution of values echoes the cries of the prophets to stand up for justice, righteousness, and the dignity of all throughout the ages. “If you remove the yoke from among you, the pointing of the finger, the speaking of evil, if you offer your food to the hungry and satisfy the needs of the afflicted, then your light shall rise in the darkness and your gloom be like the noonday. The Lord will guide you continually, and satisfy your needs in parched places, and make your bones strong; and you shall be like a watered garden, like a spring of water, whose waters never fail. Your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to live in.” (Isaiah 58) “The believers, both men and women are in charge of and responsible for one another; they all enjoin the doing of what is right and forbid the doing of what is wrong.” (Qu’ran 9:71) “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. -

Righting Wrongs

Binkley Baptist Church presents The 2014 Seymour Symposium* Righting Wrongs: Justice, the Church, and Public Discourse Friday-Sunday October 24-26 Keynote Speakers Event Schedule Friday, October 24, 2014 Rev. Dr. William J. Barber, II 4-4:30 pm Registration & Coffee This year’s symposium convenes Protestant minister and 4:30-6 pm The Battle to End Poverty in NC some of the greatest prophetic President of the NC NAACP Billy Barnes, Gene Nichol voices in North Carolina to and political leader who has 6-6:45 pm Dinner ($10) & Table Discussion address the social justice issues of been featured on CNN, 7-8:30 pm The Biblical Call to Justice Rev. Dr. William Barber, II our time. MSNBC, and in the New York Times. He was named the top faith leader 8:30-9 pm Refreshments * symposium is free, to watch in 2014. Rev. Barber has spear- Saturday, October 25, 2014 Friday dinner is $10 pre-registration only headed the Forward Together movement, 8-8:30 am Continental Breakfast which created Moral Mondays. 8:30-10 am The Role of the Church in Righting Wrongs Rev. Dr. William Barber, II Limited Seating 10-10:20 am Coffee Break Baldemar Velasquez Register by 10/20 10:20 am-12 pm Public Policy and Justice Life-long organizer and foun- NC Rep. Verla Insko der of FLOC (Farm Laborer’s NC Senator Howard Lee Organizing Committee), Rev. US Rep. David Price Moderator: Charles Coble Velasquez obtained the first union contract for farm work- Sunday, October 26, 2014 1712 Willow Drive ers in NC. -

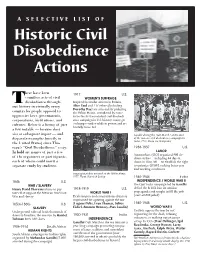

Historic CD Actions.Indd

A SELECTIVE LIST OF Historic Civil Disobedience Actions here have been 1917 U.S. countless acts of civil WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE T disobedience through- Inspired by similar actions in Britain, out history in virtually every Alice Paul and 217 others (including Dorothy Day) are arrested for picketing country by people opposed to the White House, considered by some oppressive laws, governments, to be the first nonviolent civil disobedi- corporations, institutions, and ence campaign in U.S. history; many go cultures. Below is a listing of just on hunger strikes while in prison and are brutally force-fed a few notable — because sheer size or subsequent impact — and Gandhi during the “Salt March,” at the start disparate examples (mostly in of the massive civil disobedience campaign in the United States) since Tho- India, 1930. Photo via Wikipedia. reau’s “Civil Disobedience” essay. 1936-1937 U.S. In bold are names of just a few LABOR Autoworkers (CIO) organized 900 sit- of the organizers or participants, down strikes — including 44-day sit- each of whom could merit a down in Flint, MI — to establish the right separate study by students. to unionize (UAW), seeking better pay and working conditions Suggragist pickets arrested at the White House, 1917. Photo: Harris & Ewing 1940-1944 India 1846 U.S. INDEPENDENCE / WORLD WAR II WAR / SLAVERY The Quit India campaign led by Gandhi Henry David Thoreau refuses to pay 1918-1919 U.S. defied the British ban on antiwar taxes that support the Mexican-American WORLD WAR I propaganda and sought to fill the jails War and slavery Draft resisters and conscientious objectors (over 60,000 jailed) imprisoned for agitating against the war 1850s-1860s U.S. -

The Rev Dr. William Joseph Barber II the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II Is

The Rev Dr. William Joseph Barber II The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II is the President & Senior Lecturer of Repairers of the Breach, Co-Chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call For Moral Revival; Bishop with The Fellowship of Affirming Ministries; Visiting Professor at Union Theological Seminary; Pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church, Disciples of Christ in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and the author of four books: We Are Called To Be A Movement; Revive Us Again: Vision and Action in Moral Organizing; The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics, and The Rise of a New Justice Movement; and Forward Together: A Moral Message For The Nation. Rev. Dr. Barber is also the architect of the Moral Movement, which began with weekly Moral Monday protests at the North Carolina General Assembly in 2013 and recently relaunched again online in August 2020 under the banner of the Poor People's Campaign. In 2018, Rev. Dr. Barber helped relaunch the Poor People's Campaign, which was begun by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, starting with an historic wave of protests in state capitals and in Washington, D.C., calling for a moral agenda and a moral budget to address the five interlocking injustices of systemic racism, systemic poverty, the war economy and militarism, ecological devastation, and the false moral narrative of Christian nationalism. There are currently 45 state coordinating committees across the country, mobilizing around the Poor People's Jubilee Platform and We Must Do M.O.R.E. (mobilize, organize, register, and educate people for a movement that votes). -

Herman Greene - Moral Mondays in North Carolina

Herman Greene - Moral Mondays in North Carolina For the last nine Mondays, the NAACP of North Carolina has led “Moral Monday” protests at the North Carolina legislative building. At first small, the rallies have grown to over 2,000 people per gathering. Further, over 600 people have been arrested for civil disobedience. I have been present as a protester at six of these events, though I have not been arrested. In North Carolina, as in many other states, Republicans now control both houses of the legislature and we have a Republican governor. The legislatures changed to Republican control in the 2010 election and a Republican governor was elected in 2012. With majorities in both chambers and no threat of a veto, Republicans have set out to change the direction of the state. Their goals are to make the state more competitive, create jobs, grow the economy, lower taxes, shrink government, and address moral issues, including abortion, state dependence, and laziness. North Carolina has a reputation for being a progressive Southern state. Rob Christensen, a reporter for the Raleigh News & Observer, wrote a long article on how “progressive reforms” of the last 50 years are being rolled back, including many passed with the support of Republicans. Here are some of the actions that have been taken or are proposed: In 1951 state unemployment benefits were extended from 20 to 26 weeks. Effective July 1 this was reduced to 12-20 weeks (depending on the unemployment rate), maximum benefits were reduced from $530 per week to $350 per week (the average benefit before the cut was $298.50 per week), and 170,000 unemployed workers whose state unemployment benefits have or will expire this year will be denied federal emergency unemployment benefits totaling $700 million. -

In a Whirlwind Return to the Forest, the Rev. William J. Barber II T'03

THE In a whirlwind return to The Forest, the Rev. William PREACHER J. Barber II T’03 delivered a pair of inspiring speeches that urged graduates to COMES HOME commit to a life of service. Photo Credit After the Theological School’s hooding ceremony, Barber shares a laugh with Professor of Religious Education Nancy Lynne Westfield. 6 Drew Magazine I drew.edu/magazine Summer 2017 7 Karen Mancinelli Helping is “too puny” for the task at hand, insisting these times require “a new tongue” to articulate a “moral agenda.” As he states his Others case, Barber’s voice begins to rise. Help And it’s clear when you find your moral foundation rooted in that language, then you understand something: It’s not about Others left versus right; it’s simply about right versus wrong. DREW TRUSTEE SUZANNE MERTZ The crowd inside the Concert Hall lets forth a concurring chorus SPERO C’91 OVERSEES A FAMILY of oohs and aahs. FOUNDATION FOCUSED ON NEWARK. Anywhere you pray, from Isaiah, from Jeremiah, from Ezekiel, As executive director of the MCJ Amelior Foundation, Suzanne from Luke, from James, it’s just wrong—Barber pauses—to Mertz Spero C’91 helps fund programs that foster mentoring relationships and entrepreneurship in and around Newark, take away health care from 20 million Americans. New Jersey. But that’s not all. Spero also cofounded Jersey Cares, which organizes projects to address critical community needs. But The audience—it’s his audience now—erupts in cheers. that’s not all. She also serves on the board of MENTOR, a national But Barber is just getting started. -

Voices-Of-Moral-Mondays.Pdf

Table of Contents & Credits Introduction: Mustard Seed...................................3 About the NC Council of Churches I Could Not Not Do It............................................4 Since its inception more than 75 years ago, Three Young Men.................................................5 the North Carolina Council of Churches has Six More Years......................................................6 used Christian values to promote unity and to work toward a better tomorrow. This is re- Failure to Disperse on Command..........................7 flected through the Council’s motto: “Strength Hot, Tired, and Hungry..........................................8 in Unity, Peace through Justice.” This Is What Democracy Looks Like......................9 Today, the Council consists of eighteen mem- Let the Little Children Come to Me......................10 ber denominations, with more than 6,200 con- What Does the Lord Require of You?..................11 gregations and about 1.5 million congregants across North Carolina. The Council enables My 150 New BFFs..............................................12 those denominations, congregations, and It Takes A Village to Eat Breakfast.......................13 people of faith to impact the state on issues of Furious...............................................................14 health and wellness, climate change, immigra- tion policy, farmworker rights, legislation, and Maintaining My Sanity..........................................15 much more. Created in God’s Image.......................................16 -

What's up with Education Policy in North Carolina?

March 2, 2014 Comments welcome What’s Up with Education Policy in North Carolina? By Edward B. Fiske and Helen F. Ladd [email protected]; [email protected] Explanatory Note: The purpose of this document is to help people both outside and inside North Carolina understand what is currently happening to education policy in this state. The document is neither an academic paper nor an advocacy piece. Instead it is simply our best effort to describe and to put into context the significant policy changes affecting education in North Carolina. We write it as concerned citizens and hope it will be useful to others. We have taken care to be faithful to the facts as we understand them. Whenever possible, we have checked them against relevant documents and with knowledgeable people. We welcome corrections and comments. Please send them to [email protected] One of us, Helen Ladd, The Edgar Thomson Professor of Public Policy and professor of economics at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, has published many empirical studies of education in North Carolina. The other, Edward Fiske, was the education editor of the New York Times during the 1970s and 1980s and is now an education writer and consultant. Together we have written books on education policy in New Zealand and in South Africa and articles on school finance in the Netherlands. In 2012, at the bequest of William Harrison, the then Chairman of the State Board of Education, we wrote a vision statement for public education in North Carolina. ----------------- Last year, in a seven-month frenzy of legislative hyper-activity, the Republican-controlled General Assembly of North Carolina, in concert with Republican Gov. -

The Good, the Bad and the Unclear

Democracy North Carolina 1821 Green St., Durham, NC 27705 • 919-489-1931 or 286-6000 • democracy-nc.org ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For Release Monday, Dec. 23, 2013 Contact: Bob Hall, 919-489-1931 2013: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UNCLEAR 2013 has been a challenging year for democracy in North Carolina! Here’s our take on this year and what lies ahead for 2014. GOOD – A new moral movement Moral Mondays and the Forward Together Movement: Beginning in late April, the NAACP of NC and its allies, including Democracy North Carolina, raised to a new level their opposition to a wave of ultra-conservative legislation. Gov. Pat McCrory and legislative leaders refused to meet with the coalition or seriously moderate proposals to cut unemployment benefits, shift taxes from the rich to the working poor, refuse Medicaid coverage for the poor, transfer funds from public to private schools, close women’s health clinics, and make it harder to vote yet easier for secret money to influence elections. In response, a counter wave of civil disobedience and moral witness began to resonate with the public, leading to the arrest of over 900 North Carolinians and a newly energized freedom movement that is changing the state’s political culture. US Department of Justice Intervention: Attorney General Eric Holder’s decision to file suit against North Carolina for its anti-voting elections rewrite was more than welcome. Although the state is no longer subject to preclearance under the Voting Rights Act, DOJ is using other provisions of the law and US Constitution to protect voters. -

From Fusionists to Moral Mondays: the Populist Tradition in North Carolina Politics

49th Parallel, Issue 37 (2015) David Silkenat ISSN: 1753-5894 From Fusionists to Moral Mondays: The Populist Tradition in North Carolina Politics DAVID SILKENAT – UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH The 2012 North Carolina elections brought into office a conservative Republican legislature and governor, who proceeded to pass a number of controversial measures, including significant cuts to education, restricting access to abortion, and repealing the Racial Justice Act. In response to these measures, during the summer of 2013, a coalition of liberal groups staged a series of protests outside and within the North Carolina Legislative Building called “Moral Mondays”. Led by North Carolina NAACP President Rev. William Barber II, the Moral Monday movement generated crowds numbering in the thousands, some 900 of whom were arrested for trespassing. This essay explores the ideological origins and predecessors of the Moral Monday movement. Although many of the participants see themselves as the inheritors of the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement (and to a lesser extent the Occupy movement), they also have much in common with the agrarian reform movement of the 1880s and 1890s that eventually became the Populist Party. By placing the Moral Monday movement within a “Long Populist Movement,” this essay seeks to understand the deep roots of liberal populism within North Carolina politics. The 2012 elections brought Republican control to both houses of the North Carolina legislature and the governor‟s mansion for the first time in over a century. With many of the new legislators identifying as Tea Party conservatives, the new Republican government wasted no time in enacting their conservative agenda. -

Moral Mondays in North Carolina a Social Worker's Perspective 2013

XXXVIIXXXV No. 3 3 XXXIV The No. North 6 The CarolinaNorth The North Carolina Social Carolina Social Worker Social Worker WorkerNewsletter Newsletter Newsletter August December / September 2010/JanuaryJune/July / October 2011 2011 2013 Kay Paksoy, NASW-NC Director of Advocacy, Policy, 2013 Legislative Session and Legislation is the ONLY registered lobbyist to represent the social work profession at the Lobbying for the Social Work Profession North Carolina General Assembly. By Kay Paksoy, BSW; Director of Advocacy, Policy and Legislation Your membership matters. he 2013 Legislative Session was one of the most tu- tent from voting, and more. Luckily, with the help of social multuous sessions to date. We saw some of the most work advocacy, these bills did NOT get passed. However, we Toutrageous bills introduced: preventing youth from were not so lucky in other areas. seeking mental health services without a notarized consent The state opted not to expand Medicaid, unemployment form from a parent, requiring two years of marriage coun- benefits were cut drastically to 700,000 North Carolinians, seling to couples seeking divorce (without exemption for domestic violence cases), restricting the mentally incompe- 2013 Legislative Session continued on Page 6 Moral Mondays in North Carolina A Social Worker’s Perspective By ValerieFrom Arendt, the President’sMSW, MPP; Desk, Associate Credentials Executive Received Director .................. 2 New Members .............................................................................4 housandsNASW-NC of protestors ............................................................... organized by the North Carolina.................... NAACP gathered6 over 13 weeksEthics at in the Practice North............................................................... Carolina General Assembly to give a .........voice 7to those who are going to be affected by the legislation that passed during the 2013 session. -

The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II Is the President & Senior Lecturer Of

The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II is the President & Senior Lecturer of Repairers of the Breach, Co-Chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call For Moral Revival; Bishop with The Fellowship of Affirming Ministries; Visiting Professor at Union Theological Seminary; Pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church, Disciples of Christ in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and the author of three books: Revive Us Again: Vision and Action in Moral Organizing; The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics, and The Rise of a New Justice Movement; and Forward Together: A Moral Message For The Nation. Rev. Dr. Barber is also the architect of the Forward Together Moral Movement that gained national acclaim with its Moral Monday protests at the North Carolina General Assembly in 2013. These weekly actions drew tens of thousands of North Carolinians and other moral witnesses to the state legislature. More than 1,200 peaceful protesters were arrested, handcuffed and jailed. On September 12, 2016 Rev. Dr. Barber led a “Moral Day of Action,” the largest coordinated action on state capitals in U.S. history, calling for state governments to embrace a moral public policy agenda. On February 11, 2017, he led the largest moral march in North Carolina state history, with over 80,000 people calling on North Carolina’s elected officials to embrace a moral public policy agenda. A highly sought after speaker, Rev. Dr. Barber has given keynote addresses at hundreds of national and state conferences, including the 2016 Democratic National Convention. He has spoken to a wide variety of audiences including national unions, fraternities and sororities, motorcycle organizations, drug dealer conferences, women’s groups, economic policy groups, voting rights advocates, LGBTQ equality and justice groups, environmental and criminal justice groups, small organizing committees of domestic workers, fast food workers, and national gatherings of Christians, Muslims, Jews, and other people of faith.