Indicators of Regional Development in Western Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Deformation of the Onshore Eucla Basin During the Cenozoic

Government of Western Australia Department of Mines and Petroleum RECORD 2016/10 EVOLUTION AND DEFORMATION OF THE ONSHORE EUCLA BASIN DURING THE CENOZOIC by LC Mounsher Record 2016/10 EVOLUTION AND DEFORMATION OF THE ONSHORE EUCLA BASIN DURING THE CENOZOIC by LC Mounsher Perth 2016 MINISTER FOR MINES AND PETROLEUM Hon. Sean K L’Estrange MLA DIRECTOR GENERAL, DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND PETROLEUM Richard Sellers EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Rick Rogerson REFERENCE The recommended reference for this publication is: Mounsher, LC 2016, Evolution and deformation of the onshore Eucla Basin during the Cenozoic: Geological Survey of Western Australia, Record 2016/10, 70p. National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN PDF 978-1-74168-695-1 About this publication This Record is an Honours thesis researched, written and compiled as part of a collaborative project between the Geological Survey of Western Australia (GSWA) and Curtin University, Western Australia. Although GSWA has provided support for this project including access to core, the scientific content of the Record, and the drafting of figures, was the responsibility of the author. No editing has been undertaken by GSWA. Disclaimer This product was produced using information from various sources. The Department of Mines and Petroleum (DMP) and the State cannot guarantee the accuracy, currency or completeness of the information. DMP and the State accept no responsibility and disclaim all liability for any loss, damage or costs incurred as a result of any use of or reliance whether wholly or in part upon the information provided in this publication or incorporated into it by reference. -

Ecological Character Description of the Muir-Byenup System Ramsar Site South-West Western Australia

ECOLOGICAL CHARACTER DESCRIPTION OF THE MUIR-BYENUP SYSTEM RAMSAR SITE SOUTH-WEST WESTERN AUSTRALIA Report Prepared for Department of Environment and Conservation, 2009 CENRM Report: CENRM085 i © Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, The University of Western Australia TITLE: Ecological Character Description of the Muir- Byenup System Ramsar Site South-west Western Australia: Report prepared for the Department of Environment and Conservation PRODUCED BY: CLAIRE FARRELL AND BARBARA COOK Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management The University of Western Australia Unit 1, Proudlove Parade, Albany, 6332 Telephone: (08) 9842 0839 Fax: (08) 9842 8499 Email: [email protected] PRODUCED FOR: DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION 17 Dick Perry Avenue Technology Park, Western Precinct Kensington WA 6151 CONTACT: MICHAEL COOTE DATE: SEPTEMBER 2009 PUBLICATION DATA: Farrell, C. and Cook, B. 2009. Ecological Character Description of the Muir-Byenup System Ramsar Site South-west Western Australia: Report prepared for the Department of Environment and Conservation, CENRM085. Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, University of Western Australia. September 2009. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for the development of this document was sourced jointly from the Natural Heritage Trust (NHT) and the State and Commonwealth contributions to the National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality (NAP). NHT and NAP are jointly administered by the Australian Government departments of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry -

01 Muir-Byenup Hydrology

#01 Muir-Byenup Hydrology Using empirical data to show the seasonal influence of early winter rainfall change in SW WA and Peel-Harvey Muir ─ Byenup Peter Muirden PHCC Ramsar system February 2020 This presentation is about the research I have undertaken since 2016 into the effects of rainfall change across Australia using actual rainfall and flow data; not modelled or predicted data. The work emphasises how a different presentation of these datasets more clearly shows when ‘step-changes’ in rainfall and flow have occurred at individual sites. For rainfall, these changes have then been congregated and presented spatially to more clearly show changes in rainfall. The relatively simple hydrology at the Muir-Byenup Ramsar System has been selected to show the influence of seasonal variability of rainfall and its resultant driver on streamflow. The presentation then provides describes the far more complex Swan Coastal Plain and Darling Ranges climate and hydrology with a particular emphasis on the Peel Region. 1 Albany Town ─ Annual rainfall 1400 #02 Annual rainfall - Traditional 1300 1200 presentation 1100 1000 (mm) 900 800 Annual rainfall rainfall Annual 700 600 500 400 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 This is the ‘traditional’ presentation of rainfall variability at a site; basically a ‘scatter plot’. Annual data shown here is from Albany Town is from 1877 to 2019; a period of almost 150 years. There is little than can be determined from this plot, with the only clear ‘trend’ being that it rains every year…… 2 Albany Town ─ Annual rainfall 1,400 Annual CMM ±14yr 1,300 #02 Annual rainfall - Traditional CMM ±9yr CMM ±7yr 1,200 presentation 1,100 1,000 900 800 Annual Rainfall (mm) Rainfall Annual 700 600 500 400 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020 Here the same long-term Albany Town annual rainfall data is presented with the smoothed Central Moving Mean (CMM) averages of different periods. -

Environmental Water Management in the Fitzroy River Valley Information Availability, Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs

Environmental Water Management in the Fitzroy River Valley Information availability, knowledge gaps and research needs Bradley J. Pusey The University of Western Australia & Jarrod Kath Western Australian Department of Water i Executive Summary The Fitzroy River is the largest river in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and contains significant biological, conservation and geoheritage values. Socio/cultural values, especially Indigenous values, are significant also but are not considered here. Current land use is dominated by rangeland grazing and very limited irrigated agriculture. The water resources of the basin are significant and potentially available for expanded agricultural development but the impact on the environment of increased water use, especially of groundwater is largely unknown. The current report addresses the availability of information that could be used to guide the formation and implementation of management strategies aimed at maintaining existing values. Currently available information useful in this regard is highly limited. Moreover, available information was found to be rarely in a form (i.e. quantitative relationships between flow and environmental factors) that would enable a full assessment of the impacts of different water resource use scenarios to be undertaken. Similarly, there is limited information that could provide the basis for ongoing assessment (i.e. monitoring) of the efficacy of any imposed water management strategies. Significant knowledge gaps were identified relating to five major themes: 1. The nature of aquatic habitats in the basin and their relationship to the flow regime and groundwater and including identity, extent and distribution, connectivity and conservation value; 2. Responses of riparian, floodplain and groundwater dependent vegetation to changes in water regime; 3. -

Servant Class Behaviour at the Swan River in the Context of the British Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline@ND The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Arts Papers and Journal Articles School of Arts 2016 A culture for all: Servant class behaviour at the Swan river in the context of the British Empire S Burke University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/arts_article Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This article was originally published as: Burke, S. (2016). A culture for all: Servant class behaviour at the Swan river in the context of the British Empire. Studies in Western Australian History, 31, 25-39. Original article available here: http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=160614656471281;res=IELHSS This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/arts_article/123. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Culture for All: Servant class behaviour at the Swan River in the context of the British Empire Shane Burke* Tim Mazzarol’s 1978 paper ‘Tradition, Environment and the Indentured Labourer in early Western Australia’1 is one of the earliest specific works that attempted to identify the psyche of the first British colonists at Swan River and the ‘cultural baggage’—those fears, beliefs and backgrounds—they brought with them. About 80 per cent of the adult colonists to the Swan River were described by authorities as belonging to labouring and trade occupations.2 These might be called the servant or working classes, and are hereafter simply referred to in this paper as the servant class. -

Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia Our Stories

Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia National Rural Education Conference October 2005 Darwin, Northern Territory Conference Proceedings Our Stories: Innovation and Excellence in Rural Education Edited by Colin Boylan Our Stories: Innovation and Excellence in Rural Education Proceedings of National Rural Education Conference Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia Edited by Colin Boylan Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia Inc. PO Box 379 Darling Heights Toowoomba Queensland 4350 Copyright © Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia Inc. ISBN 0 958503 9 1 SPERA Mission and Goals Mission The Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia Incorporated (SPERA) links people with a diverse range of interests in education and training to promote the development of rural Australia by: • promoting a positive view of education in rural areas and encouraging innovation and initiative in the provision of rural education services; and • providing a framework for the sharing of concerns, issues and experiences relating to education and training in rural areas. Goals SPERA advances the education and training opportunities for all people in rural Australia by: • promoting State and regional delivery systems which bring about efficient and effective education for people in rural areas; • encouraging both the collection and sharing of relevant information on the provision of education in rural areas; • conducting an annual National Conference to exchange ideas and information about education and training in rural education; and • serving as a national advocate representing rural education and training. President’s Welcome Message _____________________________________________________________________ The Society for the Provision of Education in Rural Australia, or SPERA as it is more commonly known, links people with a diverse range of interests in education and training to promote the development of rural Australia. -

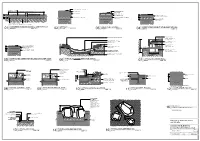

Port Hedland Landscape Guidelines Hardscape Elements Standard Drawing Details

PORT HEDLAND LANDSCAPE GUIDELINES HARDSCAPE ELEMENTS STANDARD DRAWING DETAILS STD01 - STD15 REV B 6th Feb 2018 1 of 2 varies @ A1 PORT HEDLAND LANDSCAPE GUIDELINES SOFTSCAPE ELEMENTS STANDARD DRAWING DETAILS STD16 - STD20 REV B 6th Feb 2018 2 of 2 varies @ A1 Appendix 3. Town of Port Hedland Preapproved Items ITEM DESCRIPTION PHOTO APPROVED MODEL/S 01 Compacted White Quartz Surfaces Cracker Dust 02 Compacted Red Scoria Surfaces 03 Concrete Grey or Red Tint Finishes 04 Concrete Shell Crete Finishes 05 Concrete Exposed Aggregate Finishes 06 Unit Pavers ‘Spinifex’ Paving 300x300x60mm 07 Edging Extruded Concrete – Bullnose edge 08 Edging 4mm Galvanised Steel 9 Compound 2.4m black Fencing galvanised palisade 10 Playground 2.4m black Fencing galvanised palisade- Flat top 11 Board Walks Replas Enduroplank - Grey 12 Boom Gates Leda Security Products – Model MSGF 13 Chicanes 14 Park Lighting - Greenfrog Systems Powered - Sentinel 15 Park Lighting - Greenfrog Systems Solar – Stealth 16 Bollards - Steel Galvanised Steel 17 Bollards - Flexi Pole Bollards – Recycled Charcoal Plastic Dimensions may vary and need Town approval 18 Seats Exteria Street and Park Outfitters – Parkway Seat Colour to be approved by the Town 19 Benches and Exteria Street and Tables Park Outfitters – Garden Table with Boardwalk Bench Colour to be approved by the Town 20 Boulder Seating Unquarried Sandstone Boulders 21 Litter Bin Post Exterior Street & Park Outfitters – Steel SHS Posts Hot dip galvanised finish 22 Dog Bag Woodlands AMS Dispensers Dog Bag Dispenser – Galvanised Steel. 23 Drinking Urban Fountains Fountains and Furniture – PF400 Pet Friendly Drinking Fountain. Steel RHS Mai Body. Hot Dip galvanised or powdercoat (colour to be approved by the Town) 24 Bicycle Racks Single Hoop Galvanised Bicycle Racks. -

Eocene Bryozoans Preserved in Chert from the Wilson Bluff Limestone, Eucla Basin, Western Australia

Eocene bryozoans preserved in chert from the Wilson Bluff Limestone, Eucla Basin, Western Australia MARCUS M. KEY, JR, MACKENZIE S. BURKHART & MICK O’LEARY KEY, M.M., JR, BURKHART, M.S. & O’LEARY, M. 2019:11:15. Eocene bryozoans preserved in chert from the Wilson Bluff Limestone, Eucla Basin, Western Australia. Australasian Palaeontological Memoirs 52, 85–90. ISSN 2205–8877. Fossil bryozoans preserved in cherts of the middle to upper Eocene Wilson Bluff Limestone from the Eucla area, Western Australia, are described. The Wilson Bluff Limestone was deposited in the broad shallow epicontinental Eucla Basin, which underlies the Nullarbor Plain and extends offshore into the Great Australian Bight. It is exposed at the base of the Nullarbor Plain sea cliffs and in caves in the Nullarbor Plain. The Wilson Bluff Limestone is a fine-grained, medium- to thick-bedded, chalky, bryozoan-rich limestone with abundant chert nodules. Volumetrically, the most important fossils are bryozoans. Thin sections from three samples of Aboriginal chert artifacts and two samples of chert from well cuttings were prepared. Due to the lack of frontal wall zooecial morphology, species were determined from zoarial habit, branch width, and zooecium diameter. Sixteen colonies could be assigned to three species: the cheilostomes Adeonellopsis sp. and Cellaria rigida, and the cyclostome Idmonea geminata. This species diversity preserved in chert is far lower than in previous studies of the non-chert component of the Wilson Bluff Limestone. This was attributed to the poor preservation resulting from the silicification process. Marcus M. Key, Jr ([email protected]) Department of Earth Sciences, Dickinson College, PO Box 1773, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA; Mackenze S. -

Mudrooroo: a Likely Story

Mudrooroo: A Likely Story Identity and Belonging in Postcolonial Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Maureen Clark, B.A. (Hons. First Class) Faculty of Arts 2003 Contents Acknowledgments Abstract Introduction i Part I I. Mudrooroo.author 1 II. A Question of Belonging Somewhere 19 III. The Death of the Mother 58 Part II IV. Belonging Nowhere: The Wildcat Trilogy 76 V. Vampirising Oppositional Histories: Long Live Sandawara 122 VI. Shared Histories and Shifting Identities: Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World 156 VII. Spectral Paradise: The Kwinkan 188 VIII. Violent Histories of Identity and Belonging: Master of the Ghost Dreaming 216 IX. Seductive (In)human(e) Entanglements: 242 The Vampire Trilogy Conclusion 290 Bibliography 303 Acknowledgments A culturally sensitive project such as this could never have been undertaken without the help and support of a number of people. I should like to say here that I am indebted in particular to the unfailingly generous efforts and encouragement of my supervisor Associate Professor Gerry Turcotte, during what has sometimes been an emotionally fraught journey. For his magnanimous responses to my draft chapters, I am also grateful to my second supervisor Associate Professor Paul Sharrad, from whose wise counsel and suggestions I have consistently benefited. Mrs. Betty Polglaze, Mudrooroo’s older sister, deserves special mention and appreciation. The trust she and other members of her family have afforded me during the time taken to complete this work is beyond measure. I would also like to thank Nyoongar Elder Rosemary van den Berg, Head of Aboriginal Studies at Curtin University of Technology Pat Dudgeon, as well as Nyoongar women Glenda Kickett and Tracey Kickett. -

CURRICULUM LINKS Years P-6

HERITAGE PERTH HASSchats CURRICULUM LINKS Years P-6 Government of Western Australian School Curriculum and Standards Authority Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) Curriculum Links INDEX Welcome to Country 2 Perth: The Noongar View 3 Where Perth Began 5 Reclaiming the Land 6 Old Courthouse Law Museum 7 Stirling Gardens 8 Government House 9 St Georges Cathedral 10 Perth Town Hall 11 Thanks to the Goldrush 12 Perth Mint 13 Perth City Council 14 Transport 15 Barrack Square and the Bell Tower 16 1 Heritage Perth, 2018 WELCOME TO COUNTRY HASSchat Curriculum Links Year P 1 2 • The ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples maintain connections to their Country/Place(ACHASSK049) 3 • Language groups of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples divides their Country/Place and differs from the surveyed boundaries of Australian states and territories (ACHASSK066) • The historical origins and significance of the days and weeks celebrated or commemorated in Australia (e.g. Australia Day, ANZAC Day, National Sorry Day) and the importance of symbols and emblems (ACHASSK064) 4 • People belong to diverse groups, such as cultural, religious and/or social groups, and this can shape identity (ACHASSK093) • The diversity and longevity of Australia's first peoples and the ways they are connected to Country/Place (e.g. land, sea, waterways, skies) and their pre-contact ways of life (ACHASSK083) • People belong to diverse groups, such as cultural, religious and/or social groups, and this can shape identity (ACHASSK093) • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples' ways of living were adapted to available resources and their connection to Country/Place has influenced their views on the sustainable use of these resources, before and after colonisation (ACHASSK089) 5 • The patterns of colonial development and settlement (e.g. -

The Coastal Habitats and Vegetation of the Kimberley Region

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 94: 197–206, 2011 The coastal habitats and vegetation of the Kimberley region I D Cresswell 1, P Bridgewater 2 & V Semeniuk 3 1 CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Flagship, GPO Box 1538, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001 2 The Wharfside, Station Place, Peel, Isle of Man, British Isles 3 V & C Semeniuk Research Group, 21 Glenmere Rd., Warwick, W.A., 6024 Manuscript received March 2011; accepted April 2011 Abstract Incorporating the areas of the rocky Kimberley Coast, flanked by the deltaic gulfs of Cambridge Gulf and King Sound, as well as the Dampier Peninsula, the Kimberley region host a complicated coastal zone with a plethora of coastal habitats. The smallest scale of habitat includes rocky cliff, scree slopes, gravelly/bouldery shore, sandy beaches, spits, dunes, tidal mud flats, alluvial fans, and the contact between some of these habitats and freshwater. The main vegetation units include mangroves, shrubby chenopods (which include succulent halophytic shrubs), saline marsh, sedgelands, rushlands, dune scrub, dune grasslands, and teatree thickets. The spatially and temporally variable landscape, sediments/soils, and hydrochemistry expressed at the coast mean that the coastal vegetation habitats are the most complex habitats in the Kimberley region. This review found that to date these have not been fully explored or described botanically. Keywords: Kimberley Coast, coast, coastal habitats, mangrove, saltmarsh, mangal, chenopod Introduction formations, soils, water availability, and climate; in the coastal zone vegetation distribution (and its component Perhaps the first general survey of coastal ecosystems flora) responds to a wider variety of environmental in Western Australia was Sauer (1965), which dealt, inter factors including physiography, groundwater alia, with the Kimberley coast. -

Groundwater Investigation Program in Western Australia (2005 to 2020)

Hydrogeological Record Series HG 10 2005 Groundwater investigation program in Western Australia (2005 to 2020) Westralia Square Hyatt Centre Level 8 141 St Georges Terrace Level 2 3 Plain Street Perth Western Australia 6000 East Perth Western Australia 6004 PO Box K822 Perth Western Australia 6842 PO Box 6740 Hay Street East Perth Western Australia 6892 Telephone (08) 9222 7000 Telephone (08) 9278 0300 Facsimile (08) 9322 1598 Facsimile (08) 9278 0301 E-mail [email protected] National Relay Service (Australian www.environment.wa.gov.au Communication Exchange) 132 544 E-mail [email protected] www.environment.wa.gov.au Hydrogeological Record Series Groundwater Investigation Program in Western Australia (2005 to 2020) HG 10 GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION PROGRAM IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA (2005 TO 2020) by S. L. Johnson, D. P. Commander, C. A. O’Boy and R. P. Lindsay Water Resource Division Department of Environment DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT HYDROGEOLOGICAL RECORD SERIES REPORT HG 10 JUNE 2005 Groundwater Investigation Program in Western Australia (2005 to 2020) HG 10 Hydrogeological Record Series Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Seth Johnson, Philip Commander, Chris O’Boy and Richard Lindsay. This report has been developed in consultation with the Allocation Branch, Kim Taylor and other departmental officers who have a knowledge of groundwater resource assessment. The information provided in this report is summarised from an unpublished hydrogeological report (HR221) and also outlined each drilling investigation project. For more information contact: Department of Environment Hyatt Centre, 2nd Floor 3 Plain Street East Perth WA 6004 Telephone (08) 9278 0300 Facsimile (08) 9278 0586 Recommended Reference The recommended reference for this publication is: Johnson, S.L., Commander, D.P., O’Boy, C.A.