Grade 12 English Othello All-In-One Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Dryden and the Late 17Th Century Dramatic Experience Lecture 16 (C) by Asher Ashkar Gohar 1 Credit Hr

JOHN DRYDEN AND THE LATE 17TH CENTURY DRAMATIC EXPERIENCE LECTURE 16 (C) BY ASHER ASHKAR GOHAR 1 CREDIT HR. JOHN DRYDEN (1631 – 1700) HIS LIFE: John Dryden was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the “Age of Dryden”. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. On December 1, 1663, he married Elizabeth Howard, the youngest daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st earl of Berkshire. -

Education Pack

Education Pack 1 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Shakespeare and the Original Twelfth Night ..................................................... 4 William Shakespeare 1564 - 1616 ...................................................................................... 5 Elizabethan and Jacobean Theatre ..................................................................................... 6 Section 2: The Watermill’s Production of Twelfth Night .................................................. 10 A Brief Synopsis .............................................................................................................. 11 Character Map ................................................................................................................ 13 1920s and Twelfth Night.................................................................................................. 14 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................. 16 Actor’s Blog .................................................................................................................... 20 Two Shows, One Set ........................................................................................................ 24 Rehearsal Diary ............................................................................................................... 26 Rehearsal Reports .......................................................................................................... -

Notes on the Bacon-Shakespeare Question

NOTES ON THE BACON-SHAKESPEARE QUESTION BY CHARLES ALLEN BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ftiucrsi&c press, 1900 COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY CHARLES ALLEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GIFT PREFACE AN attempt is here made to throw some new light, at least for those who are Dot already Shakespearian scholars, upon the still vexed ques- tion of the authorship of the plays and poems which bear Shakespeare's name. In the first place, it has seemed to me that the Baconian ar- gument from the legal knowledge shown in the plays is of slight weight, but that heretofore it has not been adequately met. Accordingly I have en- deavored with some elaboration to make it plain that this legal knowledge was not extraordinary, or such as to imply that the author was educated as a lawyer, or even as a lawyer's clerk. In ad- dition to dealing with this rather technical phase of the general subject, I have sought from the plays themselves and from other sources to bring together materials which have a bearing upon the question of authorship, and some of which, though familiar enough of themselves, have not been sufficiently considered in this special aspect. The writer of the plays showed an intimate M758108 iv PREFACE familiarity with many things which it is believed would have been known to Shakespeare but not to Bacon and I have to collect the most '; soughtO important of these, to exhibit them in some de- tail, and to arrange them in order, so that their weight may be easily understood and appreci- ated. -

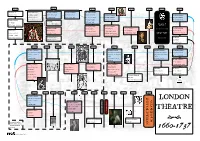

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

SUPPORT FOR THE 2021 SEASON OF THE TOM PATTERSON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE HARKINS & MANNING FAMILIES IN MEMORY OF SUSAN & JIM HARKINS LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

English Home Study

HOME STUDY-ENGLISH Spend approximately 40 minutes per day working through the activities in this booklet. You should try to spend at least 20 minutes per day reading something of your own choice You do not need to print the booklet out but you might want to use paper to record your responses. You should work through the activities in the order they appear in the booklet. Monday 1. Vocabulary (5 minutes per day) 2. Develop your knowledge – Shakespeare and his family 3. Check your understanding – Test Yourself Tuesday 1. Vocabulary (5 minutes per day) 2. Develop your knowledge – Context – What influenced Shakespeare’s writing. 3. Check your understanding- Brain Dump Wednesday 1. Vocabulary (5 Minutes per day) 2. Extended Response 1: Complete this task to demonstrate your understanding and return to your teacher via email for feedback. Thursday 1. Vocabulary (5 minutes per day) 2. Develop your knowledge – The Globe Theatre 3. Check your understanding – Test Yourself Friday 1. Vocabulary (5 Minutes per day) 2. Extended Response 2: Complete this task to demonstrate your understanding and return to your teacher via email for feedback. Extension Tasks: A few things you may enjoy doing if you have time. HOME STUDY-ENGLISH FOCUS ON VOCABULARY TASK: Use LOOK, COVER, WRITE, CHECK to learn the following definitions. Word Definition bard A poet; in olden times, a performer who told heroic stories to musical accompaniment brawl a noisy quarrel or fight Courtier a person who attends a royal court as a companion or adviser to the king or queen. Globe -

The Sonnets and Shorter Poems

AN ANALYSIS OF A NOTEBOOK OF JAMES ORCHARD HALLIWELL-PHILLIPPS THE SONNETS AND SHORTER POEMS by ELIZABETH PATRICIA PRACY A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY The Shakespeare Institute Faculty of Arts The University of Birmingham March 1999 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. O t:O SYNOPSIS The thesis starts with an Introduction which explains that the subject of the work is an analysis of the Notebook of J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps dealing with the Sonnets and shorter poems of Shakespeare owned by the Shakespeare Centre Library, Stratford-upon- Avon. This is followed by an explanation of the material and methods used to examine the pages of the Notebook and a brief account of Halliwell-Phillipps and his collections as well as a description of his work on the life and background of Shakespeare. Each page of the Notebook is then dealt with in order and outlined, together with a photocopy of Halliwell-Phillipps1 entry. Entries are identified where possible, with an explanation and description of the work referred to. -

Download Full-Text

William S h ak e s p e ar e : an overview of his life, times, and work an NAC English Theatre company educational publication THE NATIONAL ARTS CENTRE ENGLISH THEATRE PROGRAMMES FOR STUDENT AUDIENCES Peter Hinton Artistic Director, English Theatre This backgrounder was written and researched by Jane Moore for the National Arts Centre, English Theatre. Copyright Jane Moore, 2008. It may be used solely for educational purposes. The National Arts Centre English Theatre values the feedback of teachers on the content and format of its educational materials. We would appreciate your comments or suggestions on ways to improve future materials. Comments may be directed to Martina Kuska, either by email at [email protected] or fax at (613) 943 1401. Made possible in part by the NAC Foundation Donors’ Circle Table of Contents page(s) Section I: Introduction to Shakespeare............................................................................................1 - 3 William Shakespeare: Who was he, and why do we study him? .................................................1 Shakespeare‘s biography................................................................................................... 1 œ 2 Shakespeare‘s plays .......................................................................................................... 2 œ 3 Section II: Shakespeare and the Sanders Portrait............................................................................ 4 œ 5 What did Shakespeare look like? ..............................................................................................4 -

TWELFTH NIGHT Education Pack June 2014

Education Pack © Guildford Shakespeare Company Trust Ltd 2014 Education Pack This education pack has been written by GSC to complement the stage production in June 2014, staged at the Guildford Castle Gardens. The information contained in here can be used as preparation material before seeing the performance or as follow-up work afterwards in the class room. This pack is suitable for Year 9 and above. This pack contains: 1. GSC – our approach to Shakespeare 2. Cast/Character and Creative Team List 3. Synopsis 4. Shakespeare’s Language 5. The Origins of Twelfth Night 6. Interview with Director Tom Littler 7. Twelfth Night Mood Boards and Costume Designs 8. Practical classroom exercise taken from the rehearsal room. Practical in-school workshops on Twelfth Night can be booked, with actors coming into your school to work on the play. Please see www.guildford-shakespeare-company.co.uk or call 01483 304384 for more details. © Guildford Shakespeare Company Trust Ltd 2014 Education Pack “One of the strongest and most consistent companies operating in and around London” PlayShakespeare.com, 2011 Guildford Shakespeare Company is a professional site-specific theatre company, specialising in Shakespeare. Our approach places the audience right at the heart of the action, immersing them in the world of the play, thereby demystifying the legend that Shakespeare is for an elite, educated few but rather is immediate and accessible to everyone. “…to be spellbound, amused and to follow every moment of text and to want the production never to end…one of the best evenings of theatre I have ever been privileged to attend.” Audience member 2011 We want our 21st Century audiences to experience the same thrill and excitement that Shakespeare’s original audiences must have felt when they first saw the Ghost appear in Hamlet, the rousing battle cry of Henry V, and edge-of-your-seat anticipation in The Comedy of Errors. -

A Digital Production Spring 2021

A Digital Production Spring 2021 By William Shakespeare | Directed by Sophie Franco All original material copyright © 2021 Seattle Shakespeare Company CONTENT Touring Spring 2019. Photo by John Ulman Welcome Letter..........................................................................1 Plot and Characters...................................................................2 Educator Resource Guide Resource Educator ROMEO Y JULIETA Y ROMEO Articles Biography: William Shakespeare.........................................................3 Theater Audiences: Then and Now.....................................................4 At a Glance Modern Shakespeare Adaptations......................................................5 Reflection & Discussion Questions...........................................6 Placing the Production...............................................................8 Activities Cross the Line: Quotes.........................................................................9 Compliments and Insults...................................................................10 Cross the Line: Themes......................................................................11 Diary/Blog...........................................................................................11 The Art of Tableaux............................................................................12 Shakebook.....................................................................................13-14 All original material copyright © 2021 Seattle Shakespeare Company WELCOME -

Age of Dryden Summary

AGE OF DRYDEN SUMMARY John Dryden, (born August 9 [August 19, New Style], 1631, Aldwinkle, Northamptonshire, England—died May 1 [May 12], 1700, London), English poet, dramatist, and literary critic who so dominated the literary scene of his day that it came to be known as the Age of Dryden. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. When in May 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne, Dryden joined the poets of the day in welcoming him, publishing in June Astraea Redux, a poem of more than 300 lines in rhymed couplets. -

Julius Caesar Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare directed by David Muse April 27—July 6, 2008 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production of The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare! A Brief History of the Audience…………………….1 This season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company About the Playwright presents eight plays by William Shakespeare and On William Shakespeare…………………………………3 other classic playwrights. The mission of all Education Department programs is to deepen Elizabethan England……………………………………….4 understanding, appreciation and connection to Shakespeare’s Works……………………………………….5 classic theatre in learners of all ages. One Shakespeare’s Verse and Prose……………………..7 approach is the publication of First Folio Teacher A Timeline of Western World Events…….……...9 Curriculum Guides. About the Play For the 2007-08 season, the Education Synopsis of Julius Caesar…………………….…….…10 Department will publish First Folio Teacher Following the Leader…………………………….…..…11 Curriculum Guides for our productions of The Cast of Characters……..…...………………..…………..13 Taming of the Shrew, Tamburlaine, Argonautika Brutus’ Dilemma………………..……..……………..……15 and Julius Caesar. First Folio Guides provide Friends, Romans, Countrymen … What was it information and activities to help students form like to be a Roman?.....………………………………….16 a personal connection to the play before attending the production at the Shakespeare Classroom Connections Theatre Company. First Folio Guides contain • Before the Performance……………………………18 material about the playwrights, their world and the plays they penned. Also included are (Re)Making History approaches to explore the plays and Mysticism in Julius Caesar productions in the classroom before and after What Will People do for Power? the performance.