Case Report Fatal Veno-Occlusive Disease (VOD)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tanibirumab (CUI C3490677) Add to Cart

5/17/2018 NCI Metathesaurus Contains Exact Match Begins With Name Code Property Relationship Source ALL Advanced Search NCIm Version: 201706 Version 2.8 (using LexEVS 6.5) Home | NCIt Hierarchy | Sources | Help Suggest changes to this concept Tanibirumab (CUI C3490677) Add to Cart Table of Contents Terms & Properties Synonym Details Relationships By Source Terms & Properties Concept Unique Identifier (CUI): C3490677 NCI Thesaurus Code: C102877 (see NCI Thesaurus info) Semantic Type: Immunologic Factor Semantic Type: Amino Acid, Peptide, or Protein Semantic Type: Pharmacologic Substance NCIt Definition: A fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), with potential antiangiogenic activity. Upon administration, tanibirumab specifically binds to VEGFR2, thereby preventing the binding of its ligand VEGF. This may result in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and a decrease in tumor nutrient supply. VEGFR2 is a pro-angiogenic growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase expressed by endothelial cells, while VEGF is overexpressed in many tumors and is correlated to tumor progression. PDQ Definition: A fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), with potential antiangiogenic activity. Upon administration, tanibirumab specifically binds to VEGFR2, thereby preventing the binding of its ligand VEGF. This may result in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and a decrease in tumor nutrient supply. VEGFR2 is a pro-angiogenic growth factor receptor -

Oligodendroglial Tumor Chemotherapy Using “Decreased-Dose- Intensity”

Oligodendroglial Abstract—The authors propose “decreased-dose-intensity” PCV (procarbazine, lomustine [CCNU], and vincristine) chemotherapy for Asian patients with oli- tumor chemotherapy godendroglial tumors. In this study, all seven patients with oligodendroglioma using “decreased-dose- (OD) and eight with anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO) had objective responses or stable disease. Median progression-free survival was greater than 29 intensity” PCV: A months (OD) and 36.5 months or greater (AO); 86% of patients with OD and Singapore experience 63% with AO remain progression-free. Twenty-four Common Toxicity Criteria Grade 3/4 adverse events were noted. NEUROLOGY 2006;66:247–249 A.U. Ty, MD; S.J. See, MD; J.P. Rao, MD; J.B.K. Khoo, MD, FRCR; and M.C. Wong, FRCP Oligodendroglial tumors are among the most chemo- (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease, and progressive dis- 3 ϩ sensitive of human solid malignancies. In terms of ease (PD) were used. The proportion of [CR PR] constituted the objective response rate. Progression-free survival (PFS) was the cost and availability, PCV (procarbazine, lomustine period from initiation of chemotherapy to disease progression or [CCNU], and vincristine) chemotherapy is the most death. Grade 3/4 Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC version 2.0) viable chemotherapeutic option for patients with oli- adverse events (AEs) were noted. godendroglial tumors in Asia. PCV-associated toxic- ity, particularly cumulative myelosuppression, is Results. Treatment outcome and PFS data are summa- well described among white patients.1,2 There are no rized in table 1. No patient had development of PD while reports in the published literature describing Asian undergoing chemotherapy. -

Ep 2569287 B1

(19) TZZ _T (11) EP 2 569 287 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 239/46 (2006.01) 09.07.2014 Bulletin 2014/28 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 11731562.2 PCT/US2011/036245 (22) Date of filing: 12.05.2011 (87) International publication number: WO 2011/143425 (17.11.2011 Gazette 2011/46) (54) COMPOUNDS USEFUL AS INHIBITORS OF ATR KINASE VERBINDUNGEN ALS HEMMER DER ATR-KINASE COMPOSÉS UTILISABLES EN TANT QU’INHIBITEURS DE LA KINASE ATR (84) Designated Contracting States: • VIRANI, Aniza, Nizarali AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Abingdon GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO Oxfordshire OX144RY (GB) PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR • REAPER, Philip, Michael Abingdon (30) Priority: 12.05.2010 US 333869 P Oxfordshire OX144RY (GB) (43) Date of publication of application: (74) Representative: Coles, Andrea Birgit et al 20.03.2013 Bulletin 2013/12 Kilburn & Strode LLP 20 Red Lion Street (73) Proprietor: Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. London WC1R 4PJ (GB) Boston, MA 02210 (US) (56) References cited: (72) Inventors: WO-A1-2010/054398 WO-A1-2010/071837 • CHARRIER, Jean-Damien Abingdon • C. A. HALL-JACKSON: "ATR is a caffeine- Oxfordshire OX144RY (GB) sensitive, DNA-activated protein kinase with a • DURRANT, Steven, John substrate specificity distinct from DNA-PK", Abingdon ONCOGENE, vol. 18, 1999, pages 6707-6713, Oxfordshire OX144RY (GB) XP002665425, cited in the application • KNEGTEL, Ronald, Marcellus Alphonsus Abingdon Oxfordshire OX144RY (GB) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0224667 A1 AZUMA Et Al

US 20170224667A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0224667 A1 AZUMA et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 10, 2017 (54) CANCER CHEMOPREVENTIVE AGENT (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (71) Applicants: Arata AZUMA, Mitaka-shi, Tokyo Oct. 15, 2014 (JP) ................................. 2014-210690 (JP); KDL, Inc., Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Publication Classification (JP) (51) Int. Cl. (72) Inventors: Arata AZUMA, Tokyo (JP); Yukiko A6II 3/448 (2006.01) MIURA, Tokyo (JP) A6II 45/06 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .......... A61K 31/4418 (2013.01); A61K 45/06 (21) Appl. No.: 15/519,360 (2013.01) (22) PCT Filed: Apr. 21, 2015 (57) ABSTRACT (86) PCT No.: PCT/UP2015/062117 Provided is a medicine for cancer chemoprevention, the medicine being characterized by containing, as an active S 371 (c)(1), ingredient, pirfenidone or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt (2) Date: Apr. 14, 2017 thereof. Patent Application Publication Aug. 10, 2017 US 2017/0224667 A1 FG. 3 : E 838 C. ii-ECE 8A: i: 833 A883 :8. AER 8 ; ::::A; CARY 88C3S REAE i ! 3: R.EC8: 33 -x 8.8 : 88 38 3: & 2. US 2017/0224667 A1 Aug. 10, 2017 CANCER CHEMOPREVENTIVE AGENT lead to an increase in lung cancer risk (non-patent document 2-3). Although a certain number of new compounds have TECHNICAL FIELD been reported to show chemopreventive activities, none of 0001. This invention is in the field of cancer chemopre them has shown effects in human. (patent document 1-6). vention. More precisely, this invention is to provide the 0008 Pirfenidone, 5-methyl-1-phenyl-2-(1H)-pyridone, method of cancer chemoprevention using the drug contain is widely known as an effective drug for the prevention and ing pirfenidone as a pharmacological active ingredient. -

Multistage Delivery of Active Agents

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 (12) United States Patent (io) Patent No.: US 10,143,658 B2 Ferrari et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 4, 2018 (54) MULTISTAGE DELIVERY OF ACTIVE 6,355,270 B1 * 3/2002 Ferrari ................. A61K 9/0097 AGENTS 424/185.1 6,395,302 B1 * 5/2002 Hennink et al........ A61K 9/127 (71) Applicants:Board of Regents of the University of 264/4.1 2003/0059386 Al* 3/2003 Sumian ................ A61K 8/0241 Texas System, Austin, TX (US); The 424/70.1 Ohio State University Research 2003/0114366 Al* 6/2003 Martin ................. A61K 9/0097 Foundation, Columbus, OH (US) 424/489 2005/0178287 Al* 8/2005 Anderson ............ A61K 8/0241 (72) Inventors: Mauro Ferrari, Houston, TX (US); 106/31.03 Ennio Tasciotti, Houston, TX (US); 2008/0280140 Al 11/2008 Ferrari et al. Jason Sakamoto, Houston, TX (US) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignees: Board of Regents of the University of EP 855179 7/1998 Texas System, Austin, TX (US); The WO WO 2007/120248 10/2007 Ohio State University Research WO WO 2008/054874 5/2008 Foundation, Columbus, OH (US) WO WO 2008054874 A2 * 5/2008 ............... A61K 8/11 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this OTHER PUBLICATIONS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Akerman et al., "Nanocrystal targeting in vivo," Proc. Nad. Acad. Sci. USA, Oct. 1, 2002, 99(20):12617-12621. (21) Appl. No.: 14/725,570 Alley et al., "Feasibility of Drug Screening with Panels of Human tumor Cell Lines Using a Microculture Tetrazolium Assay," Cancer (22) Filed: May 29, 2015 Research, Feb. -

WO 2017/074211 Al 4 May 20 17 (04.05.2017) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/074211 Al 4 May 20 17 (04.05.2017) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 38/47 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/RU20 15/000721 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 29 October 2015 (29.10.201 5) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (72) Inventors; and (71) Applicants : GENKIN, Dmitry Dmitrievich [RU/RU]; (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every Konstantinovsky pr., 26, kv. l , St.Petersburg, 1971 10 (RU). kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, TETS, Georgy Viktorovich [RU/RU]; ul. Pushkinskaya, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 13, kv.49, St.Petersburg, 191040 (RU). -

Efficacy and Feasibility of Procarbazine, Ranimustine and Vincristine Chemotherapy, and the Role of Surgical Resection in Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 25: 3715-3724 (2005) Efficacy and Feasibility of Procarbazine, Ranimustine and Vincristine Chemotherapy, and the Role of Surgical Resection in Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma MASAAKI YAMAMOTO1, MITSUTOSHI IWAASA1, MASANI NONAKA1, HITOSHI TSUGU1, KAZUKI NABESHIMA2 and TAKEO FUKUSHIMA1 Departments of 1Neurosurgery and 2Pathology, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka 814-0180, Japan Abstract. The safety, tolerance and preliminary efficacy of a and the response rate was high. Thus, wide resection with a chemotherapy regimen consisting of procarbazine (PCB), risk of major neurological morbidity due to nearby functionally ranimustine (MCNU) and vincristine (VCR) were assessed for critical areas can be avoided. However, since the relapse rate patients with newly diagnosed supratentorial anaplastic was high, a second-line chemotherapy should be developed for oligodendroglioma. Materials and Methods: Between October anaplastic oligodendroglioma to improve the long-term control 1999 and September 2003, 5 patients were enrolled. The initial of the disease. regimens were prescribed as adjuvant therapy in conjunction with radiotherapy following standard surgical treatment. All Oligodendroglioma is a rare, although increasingly more patients received a chemotherapy comprising ranimustine (100 common, primary brain tumor (1), which represents 4 to mg/m2) intravenously on Day 1, procarbazine (60 mg/m2) on 15% of primary glial tumors (2-6). Significant attention has Days 8 to 21, and vincristine (1.4 mg/m2, maximum total 2 been focused on oligodendrogliomas because of their mg) on Days 8 and 29. The cycles were repeated every 8 weeks unique chemosensitivity compared with astrocytomas (7, 8). until tumor progression was evident, or for a total of 6 cycles Many patients with new or recurrent anaplastic over a 1-year period. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] BMJ Open Pediatric drug utilization in the Western Pacific region: Australia, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan Journal: BMJ Open ManuscriptFor ID peerbmjopen-2019-032426 review only Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the 27-Jun-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Brauer, Ruth; University College London, Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy Wong, Ian; University College London, Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy; University of Hong Kong, Centre for Safe Medication Practice and Research, Department -

5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy Can Target Aggressive Adult T Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma Resistant to Convention

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE www.nature.com/scientificreportsprovided by Okayama University Scientific Achievement Repository OPEN 5‑aminolevulinic acid‑mediated photodynamic therapy can target aggressive adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma resistant to conventional chemotherapy Yasuhisa Sando1, Ken‑ichi Matsuoka1*, Yuichi Sumii1, Takumi Kondo1, Shuntaro Ikegawa1, Hiroyuki Sugiura1, Makoto Nakamura1, Miki Iwamoto1, Yusuke Meguri1, Noboru Asada1, Daisuke Ennishi1, Hisakazu Nishimori1, Keiko Fujii1, Nobuharu Fujii1, Atae Utsunomiya2, Takashi Oka1* & Yoshinobu Maeda1 Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging treatment for various solid cancers. We recently reported that tumor cell lines and patient specimens from adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) are susceptible to specifc cell death by visible light exposure after a short‑term culture with 5‑aminolevulinic acid, indicating that extracorporeal photopheresis could eradicate hematological tumor cells circulating in peripheral blood. As a bridge from basic research to clinical trial of PDT for hematological malignancies, we here examined the efcacy of ALA‑PDT on various lymphoid malignancies with circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood. We also examined the efects of ALA‑PDT on tumor cells before and after conventional chemotherapy. With 16 primary blood samples from 13 patients, we demonstrated that PDT efciently killed tumor cells without infuencing normal lymphocytes in aggressive diseases such as acute ATL. Importantly, PDT could eradicate acute ATL cells remaining after standard chemotherapy or anti‑CCR4 antibody, suggesting that PDT could work together with other conventional therapies in a complementary manner. The responses of PDT on indolent tumor cells were various but were clearly depending on accumulation of protoporphyrin IX, which indicates the possibility of biomarker‑guided application of PDT. -

Proficient Human Colorectal Cancer Cells

Differential cytotoxicity of anticahcer agents in hMutSα-deficient and -proficient human colorectal cancer cells lichiro UCHIDA and Xiaoling ZHONG1 1Department of Molecular Biology and 21st Department of Surgery , Toho University School of Medicine, Tokyo 143-8540, Japan Abstract: Mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient cells exhibit drug resistance to several anticancer agents in- cluding N-methyl-AP-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), cisplatin, and adriamycin. Since these agents are potent mutagens, it is possible to select resistant clones of tumor cells during chemotherapy. Prior to determining whether drug cytotoxicity was altered by MMR-deficiency, mutation in the (A)8 repeat region of the hMSH3 gene of the MMR-deficient human colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 and the MMR-proficient human chromosome 3-transferred HCT116 (HCT116+ch3) was comfirmed. A screening method was then determined using MNNG cyto- toxicity in both cell lines and 20 additional anticancer agents were examined. Clonogenic cy- totoxic assay revealed in 8 anticancer agents (streptozotocin, 5-fluorouracil, tegafur, bleomycin, mitomycin C, vinblastine, vincristine, and nidoran) maintaining the desired level of cytotoxicity required a higher concentration in HCT116 than in HCT116+ch3. Cytosine0-13- arabinofuranoside, chlorambucil, and epirubicin were more cytotoxic to HCT116. Dacarbazine, nitrogen mustard, 31-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, aclarubicin, neocarzinostatin, actinomycin D, and peplomycin possessed similar cytotoxicity. These results suggest that drugs with higher or uncompromised sensitivity can circumvent drug resistance due to MMR-deficiency in tumor cells. Key words: mismatch repair deficiency, drug resistant, human colorectal cancer cells, circum- vention hMSH23'4),hMSH35), hMSH6 (GTBP or p160)", Introduction hA4LH18'9),hPMS2, and hPMS11°) have been defined by cytogenetic, biochemical, and molecu- The mismatch repair (MMR) system plays an lar biological studies. -

Human Leukocyte Antigen Class II Expression Is a Good Prognostic Factor in Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Human leukocyte antigen class II expression is a good prognostic factor in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma Mai Takeuchi, 1 Hiroaki Miyoshi, 1 Naoko Asano, 2 Noriaki Yoshida, 1,3 Kyohei Yamada, 1 Eriko Yanagida, 1 Mayuko Moritsubo, 1 Michiko Nakata, 1 Takeshi Umeno, 1 Takaharu Suzuki, 1 Satoru Komaki, 1 Hiroko Muta, 1 Takuya Furuta, 1 Masao Seto 1 and Koichi Ohshima 1 1Department of Pathology, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Fukuoka; 2Department of Molecular Diagnostics, Nagano Prefectural Shinshu Medical Center, Suzaka, Nagano and 3Department of Clinical Studies, Radiation Effects Research Foundation, Hiroshima, Japan ©2019 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2018.205567 Received: August 28, 2018. Accepted: January 9, 2019. Pre-published: January 10, 2019. Correspondence: KOICHI OHSHIMA - [email protected] A B C D Supplemental figure 1. Expression patterns of PD-L1 and PD-1. A) Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on microenvironmental stromal cells (miPD-L1). miPD-L1s have irregular shaped cytoplasm with round small nuclei without atypia. B) PD-L1 expression on neoplastic cells (nPD-L1). PD-L1-positive tumor cells have large atypical nuclei with well-circumscribed cytoplasm. C) Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) expression on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). PD-1 positive TILs are small and scatter among tumor cells. D) PD-1 expression on tumor cells. PD-1 expressing tumor cells are large and have atypical nuclei. HLA class II miPD-L1 PD-1+ TIL HLA class II Positive Negative miPD-L1 Positive Negative PD-1+TILs PD-1+ TILs ≥ 10/hpf PD-1+ TILs < 10/hpf Supplemental figure 2. -

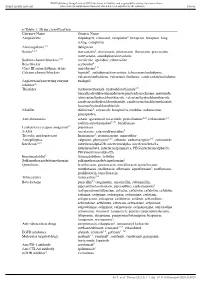

E-Table 1. Drug Classification Category Name Generic Name

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Thorax e-Table 1. Drug classification Category Name Generic Name Antiplatelets clopidogrel, cilostazol, ticlopidine2, beraprost, beraprost–long acting, complavin Anticoagulants 2,3 dabigatran Statins1,2,3 atorvastatin2, simvastatin, pitavastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, amlodipine/atorvastatin Sodium channel blockers4,5† mexiletine, aprindine, cibenzoline Beta blocker acebutolol2 Class III antiarrhythmic drugs amiodarone1–6 Calcium channel blockers bepridil1, amlodipine/atorvastatin, telmisartan/amlodipine, valsartan/amlodipine, valsartan/cilnidipine, candesartan/amlodipine Angiotensin/converting enzyme enalapril inhibitor2‡ Thiazides trichlormethiazide, hydrochlorothiazide3,5, benzylhydrochlorothiazide/reserpine/carbazochrome, mefruside, telmisartan/hydrochlorothiazide, valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, candesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, candesartan/trichlormethiazide, losartan/hydrochlorothiazide NSAIDs diclofenac2, celecoxib, loxoprofen, etodolac, nabumetone, pranoprofen Anti-rheumatics actarit, iguratimod, tofacitinib, penicillamine2–5, leflunomide1,3, sodium aurothiomalate2–6#, bucillamine Leukotriene receptor antagonist2* pranlukast 5-ASA mesalazine, salazosulfapyridine5 Tricyclic antidepressant Imipramine5, cromipramine, maprotiline Antiepileptics valproate, phenytoin2,3,5, ethotoin, carbamazepine2–5, zonisamide Interferon1,2,3