Agri-Environment Schemes Targeting Farmland Bird Populations Also Provide Food for Pollinating Insects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoverfly Newsletter 36

HOVERFLY NUMBER 36 NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2003 ISSN 1358-5029 This edition is being produced in the wake of the second international symposium which was held in Alicante in June. Alan Stubbs has commented below that Spain was, as expected, too dry in mid-June for many hoverflies to be found. It seems to me that the same comment is true for Britain for much of the present season; although I have had a few productive days this year, on the majority of occasions when I have been in the field hoverfly numbers have proved to be sparse as a result of the hot and very dry conditions. The growth of interest on the subject however continues unabated, as anyone who subscribes to the UK hoverfly email exchange group will testify. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 37 (which is expected to be issued in February 2004) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, Email address [email protected], to reach me by 20 December. CONTENTS II International Symposium on the Syrphidae 2 Alan Stubbs Alicante in mid June 7 Stuart Ball & Roger Morris News from the Hoverfly Recording Scheme 9 Andrew Grayson Similarity of hovering males of Eristalis horticola to those of Hybomitra distinguenda 12 Andrew Grayson Platycheirus rosarum in Yorkshire during 2002 12 Andrew Grayson A second specimen of Platycheirus amplus from Yorkshire 13 Roy Merritt A possible explanation for simultaneous hovering by Rhingia campestris 13 Roy Merritt Observations on Rhingia campestris 14 Alan Stubbs Hair colour variation in Heringia verrucula 14 Interesting recent records 15 Alan Stubbs Review: A world review of predatory hoverflies 16 1 II INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON THE SYRPHIDAE Following the very successful First International Workshop on the Syrphidae at Stuttgart in July 2001 (reviewed in Hoverfly Newsletter No. -

Hoverfly Newsletter No

Dipterists Forum Hoverfly Newsletter Number 48 Spring 2010 ISSN 1358-5029 I am grateful to everyone who submitted articles and photographs for this issue in a timely manner. The closing date more or less coincided with the publication of the second volume of the new Swedish hoverfly book. Nigel Jones, who had already submitted his review of volume 1, rapidly provided a further one for the second volume. In order to avoid delay I have kept the reviews separate rather than attempting to merge them. Articles and illustrations (including colour images) for the next newsletter are always welcome. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 49 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2010 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email:[email protected], to reach me by 20 May 2010. Please note the earlier than usual date which has been changed to fit in with the new bulletin closing dates. although we have not been able to attain the levels Hoverfly Recording Scheme reached in the 1980s. update December 2009 There have been a few notable changes as some of the old Stuart Ball guard such as Eileen Thorpe and Austin Brackenbury 255 Eastfield Road, Peterborough, PE1 4BH, [email protected] have reduced their activity and a number of newcomers Roger Morris have arrived. For example, there is now much more active 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire, PE9 1QE, recording in Shropshire (Nigel Jones), Northamptonshire [email protected] (John Showers), Worcestershire (Harry Green et al.) and This has been quite a remarkable year for a variety of Bedfordshire (John O’Sullivan). -

A Trait-Based Approach Laura Roquer Beni Phd Thesis 2020

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Pollinator communities and pollination services in apple orchards: a trait-based approach Laura Roquer Beni PhD Thesis 2020 Pollinator communities and pollination services in apple orchards: a trait-based approach Tesi doctoral Laura Roquer Beni per optar al grau de doctora Directors: Dr. Jordi Bosch i Dr. Anselm Rodrigo Programa de Doctorat en Ecologia Terrestre Centre de Recerca Ecològica i Aplicacions Forestals (CREAF) Universitat de Autònoma de Barcelona Juliol 2020 Il·lustració de la portada: Gala Pont @gala_pont Al meu pare, a la meva mare, a la meva germana i al meu germà Acknowledgements Se’m fa impossible resumir tot el que han significat per mi aquests anys de doctorat. Les qui em coneixeu més sabeu que han sigut anys de transformació, de reptes, d’aprendre a prioritzar sense deixar de cuidar allò que és important. Han sigut anys d’equilibris no sempre fàcils però molt gratificants. Heu sigut moltes les persones que m’heu acompanyat, d’una manera o altra, en el transcurs d’aquest projecte de creixement vital i acadèmic, i totes i cadascuna de vosaltres, formeu part del resultat final. -

Diptera, Sy Ae)

Ce nt re fo r Eco logy & Hydrology N AT U RA L ENVIRO N M EN T RESEA RC H CO U N C IL Provisional atlas of British hover les (Diptera, Sy ae) _ Stuart G Ball & Roger K A Morris _ J O I N T NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE NERC Co pyright 2000 Printed in 2000 by CRL Digital Limited ISBN I 870393 54 6 The Centre for Eco logy an d Hydrolo gy (CEI-0 is one of the Centres an d Surveys of the Natu ral Environme nt Research Council (NERC). Established in 1994, CEH is a multi-disciplinary , environmental research organisation w ith som e 600 staff an d w ell-equipp ed labo ratories and field facilities at n ine sites throughout the United Kingdom . Up u ntil Ap ril 2000, CEM co m prise d of fou r comp o nent NERC Institutes - the Institute of Hydrology (IH), the Institute of Freshw ater Eco logy (WE), the Institute of Terrestrial Eco logy (ITE), and the Institute of Virology an d Environmental Micro b iology (IVEM). From the beginning of Ap dl 2000, CEH has operated as a single institute, and the ind ividual Institute nam es have ceased to be used . CEH's mission is to "advance th e science of ecology, env ironme ntal microbiology and hyd rology th rough h igh q uality and inte rnat ionall) recognised research lead ing to better understanding and quantifia ttion of the p hysical, chem ical and b iolo gical p rocesses relating to land an d freshwater an d living organisms within the se environments". -

Rare Invertebrates Colonizing Green Roofs in London

URBAN HABITATS, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 1 ISSN 1541-7115 Rare Invertebrates Colonizing Green Roofs in London http://www.urbanhabitats.org Rare Invertebrates Colonizing Green Roofs in London by Gyongyver Kadas Royal Holloway University of London, Biological Sciences 4 West Heath Drive, London NW11 7QH U.K. Abstract are often more adventurous with regard to the The biodiversity potential of green roofs in places they colonize and use. Not many people London and their potential role in invertebrate associate rooftops with wildlife habitats, but if conservation and habitat mitigation were studied. suitable niches are available or provided, plants In summer and autumn 2004, I investigated three and animals will rapidly move in and establish different habitat types: green (Sedum) roofs, communities. In some cases, green roofs offer brown/biodiverse roofs, and brownfields. The the only valuable wildlife sanctuaries in our study focused on three diverse invertebrate cities and towns. Of particular importance is the groups: Araneae (spiders), Coleoptera (beetles), fact that these rooftops already exist, so no and aculeate Hymenoptera (wasps, ants, bees). A additional space has to be sacrificed. The high abundance of invertebrates were found on potential to provide habitat for wildlife on green the roofs. At least 10% of species collected at the roofs is tremendous. In London, for instance, study sites were designated nationally rare or 26,000 hectares of available roof space could be scarce, in accordance with criteria established by greened with little effort, and this would create the intergovernmental agency Natural England. 28 times the green space of Great Richmond The data indicates that green and Park (Grant, Engleback & Nicholson, 2003). -

Pdf of JHOS July 2007

JJoouurrnnaall of the HHAARRDDYY OORRCCHHIIDD SSOOCCIIEETTYY Vol. 4 No. 3 (45) July 2007 JOURNAL of the HARDY ORCHID SOCIETY Vol. 4 No. 3 (45) July 2007 The Hardy Orchid Society Our aim is to promote interest in the study of Native European Orchids and those from similar temperate climates throughout the world. We cover such varied aspects as field study, cultivation and propagation, photography, taxonomy and systematics, and practical conservation. We welcome articles relating to any of these subjects, which will be considered for publication by the editorial committee. Please send your submissions to the Editor, and please structure your text according to the “Advice to Authors ” (see website, January 2004 Journal or contact the Editor). The Hardy Orchid Society Committee President: Prof. Richard Bateman, Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3DS Chairman: Tony Hughes, 8 Birchwood Road, Malvern, Worcs., WR14 1LD, [email protected] Vice-Chairman & Field Meeting Co-ordinator: David Hughes, Linmoor Cottage, Highwood, Ringwood, Hants., BH24 3LE, [email protected] Secretary: Richard Manuel, Wye View Cottage, Leys Hill, Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, HR9 5QU, [email protected] Treasurer: Iain Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, Shewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 9RG, [email protected] Membership Secretary: Celia Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, Shewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 9RG, [email protected] Show Secretary: Eric Webster, 25 Highfields Drive, Loughborough, Leics., LE11 -

(Asteraceae). II. Correlated Paternity Within and Among Sibships

Copyright 2004 by the Genetics Society of America DOI: 10.1534/genetics.104.027714 Fine-Scale Genetic Structure and Gene Dispersal in Centaurea corymbosa (Asteraceae). II. Correlated Paternity Within and Among Sibships Olivier J. Hardy,*,†,1 Santiago C. Gonza´lez-Martı´nez,†,‡ Bruno Colas,§ He´le`ne Fre´ville,†,** Agne`s Mignot† and Isabelle Olivieri† *Laboratoire de Ge´ne´tique et Ecologie Ve´ge´tales, Universite´ Libre de Bruxelles, 1160 Brussels, Belgium, ‡Unidad de Gene´tica Forestal, Centro de Investigacio´n Forestal, Instituto Nacional de Investigacio´n Agraria y Tecnologı´a Alimentaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain, †Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier, Universite´ de Montpellier 2, 34035 Montpellier, France, §Laboratoire Fonctionnement et Evolution des Syste`mes Ecologiques, Universite´ de Paris VI, 75252 Paris, France and **De´partement Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversite´, UMR 5176 CNRS-MNHN, 91800 Brunoy, France Manuscript received February 17, 2004 Accepted for publication July 5, 2004 ABSTRACT The fine-scale pattern of correlated paternity was characterized within a population of the narrow-endemic model plant species, Centaurea corymbosa, using microsatellites and natural progeny arrays. We used classical approaches to assess correlated mating within sibships and developed a new method based on pairwise kinship coefficients to assess correlated paternity within and among sibships in a spatio-temporal perspec- tive. We also performed numerical simulations to assess the relative significance of different mechanisms promoting correlated paternity and to compare the statistical properties of different estimators of correlated paternity. Our new approach proved very informative to assess which factors contributed most to correlated paternity and presented good statistical properties. -

Species List for Field Trip to Moorend Spout with Tony Smith on 18Th June 2016

Species List for field trip to Moorend Spout with Tony Smith on 18th June 2016 17 people attended from Weston Natural History & Archaeology Group, Bristol Naturalists, Friends of Trendlewood Park, Backwell Environment Trust and Trustees & Friends of NEWT It was an overcast morning after a bright sunny start to the day. Temperature 16 degrees INSECTS Red and Black Froghopper -Cercopis vulnerata. This is a sap feeding insect and produces the familiar cuckoo spit where it deposits its offspring! It has the capability to leap more than 5 foot! Shield Bug - Troilus luridus. There are 44 different species of Shield Bug recorded in this country - a subject for study in its own right! Thick Kneed Beetle -Oedemera nobilis The male, as in most Oedemera species, possesses the hind femora very swollen, whereas in female the femora are thin. It is bright green, frequently with a golden or coppery shine; (Wikipedia) Garden chafer - Phyllopthera horticola A strong flying Beetle with chestnut coloured wing casings. It feeds on the leaves of trees, bushes and shrubs as well as garden plants. Long-winged Conehead - Conocephalus discolor. A small member of the Bush Cricket family which was once rare but is now expanding its range. Found amongst coarse vegetation. The name comes from the angled shape of its head. Common Blue Damselfly - Enallagma cyathigerum. Usually present in large numbers near to lakes and ponds. Broad Bodied Chaser (female) - Libellula depressa. Regular visitors to our ponds.. Nursery Web Spider - Pisaura mirabilis The Nursery Web Spider is a common spider of grassland and scrub, and is often seen sunbathing amongst Brambles and Stinging Nettles. -

Male Flower Beetles' Massive Femora Clamp Females in Place

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2020) 223, jeb219428. doi:10.1242/jeb.219428 INSIDE JEB Male flower beetles’ massive femora clamp females in place Having ruled out a role for the massive muscles in propelling the insects into the air, Burrows began puzzling about the insect’s lifestyle. ‘I then thought what males might do that females did not?’ he says, before turning his attention to the beetle’s mating strategy. However, filming the beetles in the act turned out to be more challenging than catching their solo take- offs; they seemed less at ease under the bright lights. Burrows waited patiently and eventually captured the male flower beetles as they beat their wings after a brief pursuit to ascend on top of the female before tightly clenching their colossal femora around the females’ abdomens. And, when Burrows captured the moment, he realised that he had seen something similar before. The males were gripping the females in exactly the same way that A female thick-legged flower beetle (Oedemera nobilis) clamped by the male’s rear a mole wrench – vice grip – holds on to limbs. Photo credit: Malcolm Burrows. the nut of a bolt without damaging it. ‘The big advantage of such a device is that it If ever an animal looked like a muscle- Filming the insects with a high-speed enables a lot of force of be applied without bound prizefighter, it has to be the male camera to capture their departures, having to be too careful’, says Burrows. thick-legged flower beetle (Oedemera Burrows remembers that the males and nobilis).Blessedwithanimpressivepair females were cooperative participants, In this case, the males’ powerful femora of saddlebag femora – thighs – the taking off spontaneously with little allow them to grip on tightly without dazzling green insects look ready to pack encouragement during the brief time damaging the females’ abdomens, which an impressive kick. -

Linking Mesoscale Landscape Heterogeneity and Biodiversity: Gardens and Tree Cover Significantly Modify Flower- Visiting Beetle Communities

Linking mesoscale landscape heterogeneity and biodiversity: gardens and tree cover significantly modify flower- visiting beetle communities Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Foster, C. W., Neumann, J. L. and Holloway, G. J. (2019) Linking mesoscale landscape heterogeneity and biodiversity: gardens and tree cover significantly modify flower-visiting beetle communities. Landscape Ecology, 34 (5). pp. 1081- 1095. ISSN 1572-9761 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980- 019-00822-x Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/84497/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00822-x Publisher: Springer All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Landscape Ecol (2019) 34:1081–1095 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00822-x (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) RESEARCH ARTICLE Linking mesoscale landscape heterogeneity and biodiversity: gardens and tree cover significantly modify flower-visiting beetle communities Christopher W. Foster . Jessica L. Neumann . Graham J. Holloway Received: 30 August 2018 / Accepted: 20 April 2019 / Published online: 3 May 2019 Ó The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Results The composition of immediately adjacent Context Maintaining biodiversity in multifunction habitat (30 m) and mesoscale landscape heterogeneity landscapes is a significant challenge. -

The Hoverflies of Marsland Nature Reserve

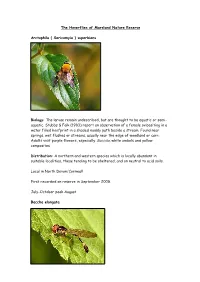

The Hoverflies of Marsland Nature Reserve Arctophila ( Sericomyia ) superbiens Biology: The larvae remain undescribed, but are thought to be aquatic or semi- aquatic. Stubbs & Falk (1983) report an observation of a female ovipositing in a water filled hoofprint in a shaded muddy path beside a stream. Found near springs, wet flushes or streams, usually near the edge of woodland or carr. Adults visit purple flowers, especially Succisa, white umbels and yellow composites Distribution: A northern and western species which is locally abundant in suitable localities, these tending to be sheltered, and on neutral to acid soils. Local in North Devon/Cornwall First recorded on reserve in September 2008. July-October peak August Baccha elongata Biology: This species is found in shady places such as woodland rides and edges, hedgerows and mature gardens, where adults may be seen hovering low amongst ground-layer plants. The larvae are aphidophagous, preying on a variety of ground-layer species in shaded situations, e.g. Uromelan jaceae on Centaurea scabiosa, Brachycaudina napelli on Aconitum, and the bramble aphid, Sitobion fragariae onRubus. It overwinters as a larva Distribution: Widely recorded throughout Britain, but like most woodland species, scarce or absent from poorly-wooded areas such as the East Anglian fens and the Scottish islands. There is considerable uncertainty about the status of B. obscuripennis which has often been regarded as a distinct species. Most records submitted to the scheme are attributed to “ Baccha spp.”, but analysis of those where separation has been attempted do not suggest any differences in range, flight period or habitat preference Brachypalpoides lenta ( Xylota lenta ) Biology: The larvae of this species occur in decaying heartwood of beech, particularly in live trees with exposed decay at ground level. -

Dipterists Digest Dipterists Digest

1 Dipterists Digest Volume 26, No. 2 2019 First records of Helina pulchella (Ringdahl) (Diptera, Muscidae) from Finland and notes on the biology of the species Dipterists Digest JAAKKO POHJOISMÄKI and ANTTI HAARTO ………………………………. 111-115 Corrections and changes to the Diptera Checklist (42) EDITOR …………………………………………………………………………………... 116 Mechanisms and patterns of feeding in some leaf-mining larvae (Diptera, Agromyzidae, Drosophilidae and Anthomyiidae) GRAHAM E. ROTHERAY ........................................................................................ 117-137 Further records of Leopoldius calceatus (Rondani) (Diptera, Conopidae) in Britain DAVID K. CLEMENTS, CHRIS BENTLEY and PAUL KITCHENER ……….. 137-138 Effects of the 2018 heatwave on British hoverflies (Diptera, Syrphidae) ROGER K.A. MORRIS and STUART G. BALL …………………………………. 139-150 Further records of Chymomyza caudatula Oldenberg (Diptera, Drosophilidae) from England IVAN PERRY …………………………………………………………………………….. 150 Nematoproctus praesectus Loew (Diptera, Dolichopodidae) new to Britain, found together with N. distendens (Meigen), and notes on their habitat preferences C. MARTIN DRAKE ………………………………………………………………... 151-160 Changes to the Irish Diptera List (29) EDITOR …………………………………………………………………………………... 160 Hoverflies (Diptera, Syrphidae) visiting ivy Hedera species ROGER K.A. MORRIS and STUART G. BALL …………………………………... 161-167 continued inside back cover Published by 2019 Vol. 26 No. 2 ISSN 0953-7260 1 2 Zaphne caudata (Zetterstedt) (Diptera, Anthomyiidae) new to the East of England (V.Cs