Rights-Based Management in International Tuna Fisheries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dewey Gillespie's Hands Finish His Featherwing

“Where The Rivers Meet” The Fly Tyers of New Brunswi By Dewey Gillespie The 2nd Time Around Dewey Gillespie’s hands finish his featherwing version of NB Fly Tyer, Everett Price’s “Rose of New England Streamer” 1 Index A Albee Special 25 B Beulah Eleanor Armstrong 9 C Corinne (Legace) Gallant 12 D David Arthur LaPointe 16 E Emerson O’Dell Underhill 34 F Frank Lawrence Rickard 20 G Green Highlander 15 Green Machine 37 H Hipporous 4 I Introduction 4 J James Norton DeWitt 26 M Marie J. R. (LeBlanc) St. Laurent 31 N Nepisiguit Gray 19 O Orange Blossom Special 30 Origin of the “Deer Hair” Shady Lady 35 Origin of the Green Machine 34 2 R Ralph Turner “Ralphie” Miller 39 Red Devon 5 Rusty Wulff 41 S Sacred Cow (Holy Cow) 25 3 Introduction When the first book on New Brunswick Fly Tyers was released in 1995, I knew there were other respectable tyers that should have been including in the book. In absence of the information about those tyers I decided to proceed with what I had and over the next few years, if I could get the information on the others, I would consider releasing a second book. Never did I realize that it would take me six years to gather that information. During the six years I had the pleasure of personally meeting a number of the tyers. Sadly some of them are no longer with us. During the many meetings I had with the fly tyers, their families and friends I will never forget their kindness and generosity. -

Fishing Tackle Related Items

ANGLING AUCTIONS SALE OF FISHING TACKLE and RELATED ITEMS at the CROSFIELD HALL BROADWATER ROAD ROMSEY, HANTS SO51 8GL on SATURDAY, 5th October 2019 at 12 noon TERMS AND CONDITIONS 7. Catalogue Description (a) All Lots are offered for sale as shown and neither A. BUYERS the Auctioneer nor Vendor accept any responsibility for imperfections, faults or errors 1. The Auctioneers as agent of description, buyers should satisfy themselves Unless otherwise stated,the Auctioneers act only as to the condition of any Lots prior to bidding. as agent for the Vendor. (b) Descriptions contained in the catalogue are the opinion of the Auctioneers and should not be 2. Buyer taken as a representation of statement or fact. (a) The Buyer shall be the highest bidder Some descriptions in the catalogue make acceptable to the Auctioneer and reference to damage and/or restoration. Such theAuctioneers shall have information is given for guidance only and the absolute discretion to settle any dispute. absence of such a reference does not imply that (b) The Auctioneer reserves the right to refuse to a Lot is free from defects nor does any reference accept bids from any person or to refuse to particular defects imply the absence of others. admission to the premises of sale without giving any reason thereof. 8. Value Added Tax In the case of a lot marked with an asterix (*) in the 3. Buyers Premium catalogue. VAT is payable on the Hammer Price. The Buyer shall pay the Auctioneer a premium of VAT is payable at the rates prevailing on the date of 18% of the Hammer Price (together with VAT at the auction. -

Langley's Trout Candy by Kevin Cohenour

Langley’s Trout Candy by Kevin Cohenour Every once in awhile a fly pattern comes along, such as the Clouser Minnow and Lefty's Deceiver, that will catch most any species. The Trout Candy has proven itself to be in that category. I first learned of this pattern in 1996 when I walked into Jacksonville’s Salty Feather JUNEFEBRUARY 20012002 fly shop. I asked owner John Bottko for a pattern I could tie for redfish and trout. He described the FLIES & LIES VIA E-MAIL Trout Candy for me. Originated by Alan Langley of Jacksonville, the Trout Candy began as a pattern to catch sea trout. But as we quickly Computer whiz Kevin Cohenour has found, it is an extremely effective redfish fly. figured out an easy way for you to receive Tied in smaller sizes (6 & 8) it has taken “Flies & Lies” via e-mail in the format of a bonefish in the keys. With a marabou tail it has “PDF” file. Your computer will probably fooled salmon and rainbows in Alaska. It will already read a PDF file with Adobe Acrobat catch ladyfish all day long, entices snook and or similar software. If not, free downloads jacks, and has even landed flounder and are available. croakers. Tied in size 1 or 2 with large eyes it We will send the June issue via mail will get down in the surf to the cruising reds. and e-mail on a trial basis, Thereafter, if you The first redfish I ever caught was on a choose, we can send your copy by e-mail size 4 Trout Candy I had tied from John’s verbal alone. -

Ring of the Rise

Ring of the Rise June 2016 Official Periodical of the Southern Sierra Fly Fishers Club Gary Silveira, Newsletter Editor President’s Message: by Chiaki Harami (haramic) fishing club presidents in our region, requesting their support. A day later, all 14 outfits were sponsored. When It’s been a very busy April and May for our Club. On April their fly fishing outfit was announced, there were cheers and 23 rd we held our 11 th Annual Rendezvous. This event is our tears of joy. I was glad to help out in a small way. major fund rising event and membership drive of the year. It was held at a new venue this year – Rivernook Campgrounds. We had a very nice small meadows area reserved and everything worked out very nicely. There’s a more detailed report on page 5 which includes pictures and the winners of our C & R Tourney. On May 14 th we held our famous Kids Academy at the Kernville Hatchery. 15 kids graduated after learning casting, knots, fly tying, entomology, conservation and catching. The kids were able to fish the hatchery and caught trout up to 5 pounds. The kids ended up getting wet from all the “splishing” and splashing from the big trout. Many of the kids caught trout on flies they tied earlier in the day, taught by Gary Applebee. All the kids had big smiles at the end of the day. There’s another more detailed report on the Kids Academy on page 6. nd On May 22 , I helped at the Casting for Recovery Retreat at Lake Arrowhead. -

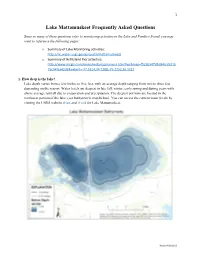

Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions

1 Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions Since so many of these questions refer to monitoring activities in the Lake and Pamlico Sound, you may want to reference the following pages: o Summary of Lake Monitoring activities: http://nc.water.usgs.gov/projects/mattamuskeet/ o Summary of Bell Island Pier activities: http://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=f52ab347d5e84ccc921b 75c34fea42d5&extent=-77.5214,34.7208,-75.2252,36.3212 1. How deep is the lake? Lake depth varies from a few inches to five feet, with an average depth ranging from two to three feet depending on the season. Water levels are deepest in late fall, winter, early spring and during years with above average rainfall due to evaporation and precipitation. The deepest portions are located in the northwest portion of the lake. (see bathymetric map below). You can access the current water levels by visiting the USGS website (East and West) for Lake Mattamuskeet. Updated 10/12/16 2 2. Why is the lake so high/low? Lake levels fluctuate on a daily, seasonal and yearly basis. Water levels are primarily determined by climatic conditions. Generally, seasonal lake levels follow a pattern of being lower in the summer due to high evaporation rates and higher in fall, winter and spring due to lower evaporation rates and greater precipitation. Lake levels will increase by a few inches after a heavy rain. During wet years with lots of precipitation, water levels will rise; during drought years, water levels will fall. You can access current water levels by visiting the USGS website for Lake Mattamuskeet (East and West). -

Fishing Programme Questionnaire

T H E F LYDRESSERS ’ G UILD Sussex Branch Newsletter JT AH E N F ULYDRESSERS A R Y 2’G 0UILD2 0 Lower Itchen Fishery report When I was offered the choice of the weekday or weekend trip, I opted for the weekday one. I By Andy Wood reasoned that the fishery would be quieter, but completely overlooked the travel implications. From a journey perspective it was, of course, anything but quiet on a workday morning. There was some sort of issue on the M27 that reduced traffic to a crawl, increasing the journey time to almost two and a half hours. However, on arriving at the fishery and seeing the river for the first time, that all became a distant memory. Despite the recent wet weather, the river was running crystal clear and the sun was shining, with virtually no wind. Probably less than perfect conditions for fishing, but one of those days when it’s simply sufficient to be out there and taking it all in. After a challenging drive up river – it felt like I was in it at times - where I got to I’ve wanted to fish the Lower Itchen for a while wondering whether my breakdown cover would because I love chalk streams. Before starting extend to some river bank in the middle of out fly fishing I always had that classic image in nowhere, we arrived at the ‘fly only’ stretch and my head that such rivers represented the parked up pinnacle of the sport. This was at least in part I quickly got my gear together, while taking in a down to the fact that for 5 wonderful years I was couple of tips from Ray, and the four of us went lucky enough to live within walking distance of our separate ways in pursuit of the ‘Lady of the the Upper Avon at Durrington, just off the Stream’. -

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Build-Up Black Book • the Build-Up Is Possibly a Darwin Locals Favorite Time of Year

BAREFOOT FISHING SAFARIS Build-Up Black Book • The Build-Up is possibly a Darwin locals favorite time of year. Less tourists, flat seas and hungry fish. • The Build-Up happens as the Wet Season approaches and is characterized by big tides, hot sticky weather, flat seas and pre spawning fish. WHAT IS THE st st BUILD-UP • Build-Up occurs from September 1 through until December 1 • It’s pre-spawn time for BIG Barramundi, King Threadfin, Black ANYWAY? Jew and Golden Snapper. • These 4 prestige species return closer to shore and upriver systems in anticipation for appropriate spawning conditions. • This is a period of heavy feeding for breeding fish making them easier to target. • THE BUILD-UP IS A SPECIAL TIME OF YEAR IN THE TOP END. TOURIST NUMBERS ARE DOWN, AND THE OCEAN IS FLAT, IT’S THE PERFECT TIME TO HEAD OUT WIDE FOR PELAGICS OR SEARCH FOR PRE SPAWNING BARRA IN CLEAN CALM WATER. • THE BUILD-UP IS THE BEST CHANCE SINCE MAY TO GET ACCESS TO GOOD NUMBERS OF BIG BARRA. FISHING THE • BARRA SCHOOL UP IN CERTAIN AREAS AT THIS TIME OF YEAR AND QUALITY BUILD-UP ELECTRONICS LIGHT UP WITH NUMEROUS BIG FISH SITTING AND WAITING FOR THE PERFECT TIME TO FEED. • CLEAN WATER AND CALM SEAS PRODUCE THE RIGHT CONDITIONS TO TARGET BIG PRE SPAWN BARRA. EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW (AND SOME THINGS YOU DON’T) • Inside this special guide you’ll find everything you need to know about a Barefoot guided fishing safari during the Build-Up and how to best prepare to ensure it truly is the trip of a lifetime. -

Susquhanna River Fishing Brochure

Fishing the Susquehanna River The Susquehanna Trophy-sized muskellunge (stocked by Pennsylvania) and hybrid tiger muskellunge The Susquehanna River flows through (stocked by New York until 2007) are Chenango, Broome, and Tioga counties for commonly caught in the river between nearly 86 miles, through both rural and urban Binghamton and Waverly. Local hot spots environments. Anglers can find a variety of fish include the Chenango River mouth, Murphy’s throughout the river. Island, Grippen Park, Hiawatha Island, the The Susquehanna River once supported large Smallmouth bass and walleye are the two Owego Creek mouth, and Baileys Eddy (near numbers of migratory fish, like the American gamefish most often pursued by anglers in Barton) shad. These stocks have been severely impacted Fishing the the Susquehanna River, but the river also Many anglers find that the most enjoyable by human activities, especially dam building. Susquehanna River supports thriving populations of northern pike, and productive way to fish the Susquehanna is The Susquehanna River Anadromous Fish Res- muskellunge, tiger muskellunge, channel catfish, by floating in a canoe or small boat. Using this rock bass, crappie, yellow perch, bullheads, and method, anglers drift cautiously towards their toration Cooperative (SRFARC) is an organiza- sunfish. preferred fishing spot, while casting ahead tion comprised of fishery agencies from three of the boat using the lures or bait mentioned basin states, the Susquehanna River Commission Tips and Hot Spots above. In many of the deep pool areas of the (SRBC), and the federal government working Susquehanna, trolling with deep running lures together to restore self-sustaining anadromous Fishing at the head or tail ends of pools is the is also effective. -

Searching for Responsible and Sustainable Recreational Fisheries in the Anthropocene

Received: 10 October 2018 Accepted: 18 February 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.13935 FISH SYMPOSIUM SPECIAL ISSUE REVIEW PAPER Searching for responsible and sustainable recreational fisheries in the Anthropocene Steven J. Cooke1 | William M. Twardek1 | Andrea J. Reid1 | Robert J. Lennox1 | Sascha C. Danylchuk2 | Jacob W. Brownscombe1 | Shannon D. Bower3 | Robert Arlinghaus4 | Kieran Hyder5,6 | Andy J. Danylchuk2,7 1Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Recreational fisheries that use rod and reel (i.e., angling) operate around the globe in diverse Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary freshwater and marine habitats, targeting many different gamefish species and engaging at least Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, 220 million participants. The motivations for fishing vary extensively; whether anglers engage in Ontario, Canada catch-and-release or are harvest-oriented, there is strong potential for recreational fisheries to 2Fish Mission, Amherst, Massechussetts, USA be conducted in a manner that is both responsible and sustainable. There are many examples of 3Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Uppsala University, Visby, recreational fisheries that are well-managed where anglers, the angling industry and managers Gotland, Sweden engage in responsible behaviours that both contribute to long-term sustainability of fish popula- 4Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, tions and the sector. Yet, recreational fisheries do not operate in a vacuum; fish populations face Leibniz-Institute -

Inside This Issue

Website: www.wffc.com Member of MMXXI No. 2 February, 2021 2021 WFFC Budget. President’s What to go fishing? Dave Schorsch will begin pub- Riffle lishing a monthly “Do-it-Yourself” Outing recommen- Have you got your dation until we can start holding Club Outings once vaccination shot yet? again. His first DIY fishing opportunities overview is Being in the B1 age included in this Creel Notes edition [pages 4 & 5] and group, I have had my it is terrific! first shot and will get I hope to see you all at the February 16th Zoom my second shot later Monthly Meeting. At that meeting I will give a short this month. Hopefully all of you will be able to receive report on what the outlook for the club to resume your shot(s) by the end of this summer so we may be in person Dinner Meetings, Outings and Education able to get together once again to go “fishing” in the Classes this year. Following the business part of our Fall and hold the Christmas Holiday Fundraiser in meeting, David Williams will be the zoom meeting’s December. speaker and will talk to us about the where and how to At the February 2nd Board Meeting, the proposed catch bass in Eastern Washington. 2021 WFFC Revenue and Expenses Budget was pre- Don’t forget to pay your 2021 WFFC Dues, they are sented and approved by the Board. It will be presented only $40 this year! to the membership for approval or rejection by an Stay Safe, get your vaccine shot and Tight Lines - emailed ballot at the end of this month, per the WFFC Jim Goedhart WFFC President Bylaws requirements. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region August 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN MERRITT ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Brevard and Volusia Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish And Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 4 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 5 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives .................................................................................6 Relationship to State Partners .....................................................................................................