Displacementand Insecurity Inarea C Ofthe West Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nablus City Profile

Nablus City Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 4102 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, and aim to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the programs and activities needed to mitigate the impact of the current insecure political, economic and social conditions in the Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Nablus Governorate. -

Palestinian Olive Agony 2018 ( a Statistical Report on Israeli Violations)

Palestinian Olive Agony 2018 ( A Statistical Report on Israeli Violations) Prepared by: Monitoring Israeli Violations Team Land Research Center Arab Studies Society - Jerusalem March 2019 ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY – Land Research Center (LRC) – Jerusalem 1 Halhul – Main Road, Tel: 02-2217239 , Fax: 02 -2290918 , P.O.Box: 35, E-mail: [email protected], URL: www.lrcj.org The olive tree have always been a thorn on the Israeli occupation’s side Deep rooted in the history of this land.. its oil is still sacred enlightening its temples Its branches play with farmers’ children.. and suffer from agonizing pain when touched by a settler’s saw That is, the Palestinian olive tree.. standing still on the face of the Israeli occupation’s sadism Burnt.. but reborn from its dust like a phoenix Cut.. but grows anew from its roots Stolen.. and when planted in their settlements. .becomes darkened and cloudy The Israeli occupiers tried to contain the olive tree , but it refused.. so they decided to uproot it from the land of Palestine , but failed and will fail The olive trees are a constant tar get by the occupation but they are still steadfast and refuses to surrender .. The olive tree stands for Palestinians' very existence, and their cultural identity and civilization, it is a testimony from history on the Palestinian land’s Arabism. Jamal Talab Al -Amleh LRC general manager Jerusalem – Palestine ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY – Land Research Center (LRC) – Jerusalem 2 Halhul – Main Road, Tel: 02-2217239 , Fax: 02-2290918 , P.O.Box: 35, E-mail: [email protected], URL: www.lrcj.org In 201 8, Land Research Center documented attacks that targeted olive trees, though daily monitoring: • 117 attacks took place , 90 of them were perpet rated by settlers from settlements nearby olive groves, while 27 were perpetrated by the occupation forces. -

West Bank Movement Andaccess Update

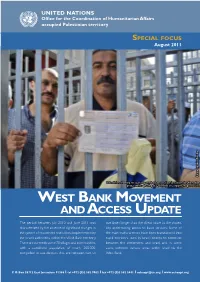

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory SPECIAL FOCUS August 2011 Photo by John Torday John Photo by Palestinian showing his special permit to access East Jerusalem for Ramadan prayer, while queuing at Qalandiya checkpoint, August 2010. WEST BANK MOVEMENT AND ACCESS UPDATE The period between July 2010 and June 2011 was five times longer than the direct route to the closest characterized by the absence of significant changes in city, undermining access to basic services. Some of the system of movement restrictions implemented by the main traffic arteries have been transformed into the Israeli authorities within the West Bank territory. rapid ‘corridors’ used by Israeli citizens to commute There are currently some 70 villages and communities, between the settlements and Israel, and, in some with a combined population of nearly 200,000, cases, between various areas within Israel via the compelled to use detours that are between two to West Bank. P. O. Box 38712 East Jerusalem 91386 l tel +972 (0)2 582 9962 l fax +972 (0)2 582 5841 l [email protected] l www.ochaopt.org AUGUST 2011 1 UN OCHA oPt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The period between July 2010 and June 2011 Jerusalem. Those who obtained an entry permit, was characterized by the absence of significant were limited to using four of the 16 checkpoints along changes in the system of movement restrictions the Barrier. Overcrowding, along with the multiple implemented by the Israeli authorities within the layers of checks and security procedures at these West Bank territory to address security concerns. -

West Bank, Undermining the Living Conditions of Many Palestinians in the West Bank

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS W EEKLY REPORT 27 JULY - 2 AUGUST 2011 Key issues The Israeli Supreme Court ordered on 2 August the dismantlement of what is considered to be the largest settlement outpost (Migron), which was built without permit on private Palestinian land. The authorities intend to relocate the settlers to an extension to be built in a nearby settlement. All settlements are illegal under International Humanitarian Law, regardless of their planning status. Settlements are also one of the main factors behind access restrictions, insecurity and displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank, undermining the living conditions of many Palestinians in the West Bank. WEST BANK Two Palestinians killed during Palestinian casualties by Israeli forces a raid Killed this week: 2 An Israeli raid into Qalandiya refugee camp, north Killed in 2011 vs. same period 2010: 8 vs. 8 of East Jerusalem, in the early morning of 1 August Injured this week: 37, inc. 36 injured in demonstrations. evolved into clashes between Israeli forces and Of whom children: 2 Palestinian stone throwers, resulting in the killing of Injured in 2011 vs. same period 2010: 962 vs. 773 two Palestinian men (aged 22 and 23) and the injury of another, all with live ammunition. Five Israeli soldiers were also injured by stones. At the time of separate incidents, Israeli settlers reportedly set the raid, residents of the camp were out in the streets fire to agricultural land belonging to the villages at the time of the early morning meal (Suhoor) of the of Turmus ‘Ayya in the Ramallah governorate and first day of Ramadan.During the week, Israeli forces Burin, ‘Awarta and Jalud in the Nablus governorate, conducted a total of 84 search and arrest operations damaging around 400 olive and almond trees. -

Chapter 5. Development Frameworks

Chapter 5 JERICHO Regional Development Study Development Frameworks CHAPTER 5. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS 5.1 Socioeconomic Framework Socioeconomic frameworks for the Jericho regional development plan are first discussed in terms of population, employment, and then gross domestic product (GDP) in the region. 5.1.1 Population and Employment The population of the West Bank and Gaza totals 3.76 million in 2005, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimation.1 Of this total, the West Bank has 2.37 million residents (see the table below). Population growth of the West Bank and Gaza between 1997 and 2005 was 3.3%, while that of the West Bank was slightly lower. In the Jordan Rift Valley area, including refugee camps, there are 88,912 residents; 42,268 in the Jericho governorate and 46,644 in the Tubas district2. Population growth in the Jordan Rift Valley area is 3.7%, which is higher than that of the West Bank and Gaza. Table 5.1.1 Population Trends (1997-2005) (Unit: number) Locality 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 CAGR West Bank and Gaza 2,895,683 3,275,389 3,394,046 3,514,868 3,637,529 3,762,005 3.3% West Bank 1,873,476 2,087,259 2,157,674 2,228,759 2,300,293 2,372,216 3.0% Jericho governorate 31,412 37,066 38,968 40,894 40,909 42,268 3.8% Tubas District 35,176 41,067 43,110 45,187 45,168 46,644 3.6% Study Area 66,588 78,133 82,078 86,081 86,077 88,912 3.7% Study Area (Excl. -

Jamma'in Town Profile

Jamma'in Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2014 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, town committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and towns in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Nablus Governorate, which aims to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Town Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Town Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Nablus Governorate. -

Optimal Sizing of Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Tanks for Sustainable Domestic Water Use in the West Bank, Palestine

water Article Optimal Sizing of Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Tanks for Sustainable Domestic Water Use in the West Bank, Palestine Sameer Shadeed * and Sandy Alawna Water and Environmental Studies Institute, An-Najah National University, Nablus P.O. Box 7, Palestine; sandy–[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In highly water-poor areas, rooftop rainwater harvesting (RRWH) can be used for a self- sustaining and self-reliant domestic water supply. The designing of an optimal RRWH storage tank is a key parameter to implement a reliable RRWH system. In this study, the optimal size of RRWH storage tanks in the different West Bank governorates was estimated based on monthly (all governorates) and daily (i.e., Nablus) inflow (RRWH) and outflow (domestic water demand, DWD) data. In the estimation of RRWH, five rooftop areas varying between 100 m2 and 300 m2 were selected. Moreover, the reliability of the adopting RRWH system in the different West Bank governorates was tested. Two-time series scenarios were assumed: Scenario 1, S1 (12 months, annual) and scenario 2, S2 (8 months, rainy). As a result, reliable curves for preliminary estimation of optimal RRWH storage tanks for the different West Bank governorates were obtained. Results show that the required storage tank for S1 (annual) is more than that of the S2 (rainy) one. The required storage tank to fulfill DWD is based on the average rooftop area of 150 m2, the average family members of 4.8, and the average DWD of 90 L per capita per day (L/c/d) varies between (75 m3 to 136 m3) and (24 m3 to 84 m3) for S2 for the different West Bank governorates. -

Occupied Palestinian Territory

Reporting period: 17 - 23 November 2015 Weekly Highlights Latest Developments (outside of the reporting period): On 24 November, a 21-year-old Palestinian man ran over Israeli forces at Za’tara checkpoint (Nablus) injuring three soldiers; the perpetrator was shot and seriously injured. On 25 November, a 16-year-old Palestinian boy died of injuries sustained earlier this month when he was shot with live ammunition by Israeli forces during clashes near the Ramallah-DCO checkpoint. On 26 November, a 19-year-old Palestinian man was shot and killed by Israeli forces during clashes at a search and arrest operation in Qattanna (Jerusalem). On 26 November, the Israeli authorities demolished 14 structures in the herding community of Al Hadidiya (northern Jordan Valley), on grounds of lack of building permits, displacing 15 people; half of the structures destroyed have been provided by humanitarian agencies following previous demolitions. T he wave of violence across the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) continued during the reporting period (17 to 23 November) resulting in eight Palestinian and six Israeli fatalities, and another 1,188 Palestinian and 21 Israeli injuries. This week recorded the largest number of Israelis killed and injured in Palestinian attacks in a single week since the start of the current escalation of violence. Between 1 October and 23 November, 92 Palestinians, including 20 children, and 17 Israelis were killed, and 10,346 Palestinians and at least 160 Israelis were injured in the oPt and Israel.[1] Six Israelis were killed and 19 others were injured in nine separate Palestinian attacks, including three stabbings, three ramming, and three shooting attacks; one of these fatalities and three of these injuries were of soldiers and policemen. -

Nablus Governorate

'Ajja 'Anza Sanur Sir Deir al Ghusun ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY Land Suitability for Rangeland - Nablus Governorate Meithalun 'Aqqaba Land Research Center Al Jarushiya This study is implemented by: Tayasir Land RSesHeaUrcWh CEeInKteAr - LRC Sa Nur Evacuated Al Judeida Bal'a Siris Funded by: Iktaba Al 'Attara Al FandaqumiyaJaba' The Italian Cooperation Tubas District Camp Tulkarm Silat adh Dhahr Maskiyyot Administrated by: January 2010 TulkarmDhinnaba Homesh Evacuated United Nations Development Program UNDP / P'APnPabta Bizzariya GIS & Mapping Unit WWW.LRCJ.ORG Burqa Supervised by: Kafr al Labad Yasid Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture Beit Imrin El Far'a Camp Ramin Far'un'Izbat Shufa Avnei Hefetz Enav Tammun Jenin Wadi al Far'a Shufa Sabastiya Talluza Tulkarm Tubas Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al Badhan Qalqiliya Nablus Ya'arit Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Roi Salfit Zawata SalitKafr Sur An Nassariya Beqaot Qusin Beit Iba Elon Moreh Jericho Ramallah Kedumim Zefon Beit Wazan Kafr JammalKafr Zibad Giv'at HaMerkaziz 'Azmut Kafr 'Abbush Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jerusalem Kedumim Sarra Salim Hajja Jit Balata Camp Bethlehem Jayyus Tell Zufin Bracha Hamra Qalqiliya Immatin Kafr QallilRujeib Beit Dajan Hebron Burin 'Asira al Qibliya 'Azzun Karne Shomron Beit Furik Alfei Menashe Ginnot ShomeronNeve Oramin Yizhar Itamar (including Itamar1,2,3,4) Habla Ma'ale Shamron Immanuel 'Awarta Mekhora Al Jiftlik 'Urif East Yizhar , Roads, Caravans, & Infrastructure Kafr Thulth Nofim Yakir Huwwara 'Einabus Beita Zamarot -

Protection of Civilians - Weekly Briefing Notes 30 November – 6 December 2005

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 30 November – 6 December 2005 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians - Weekly Briefing Notes 30 November – 6 December 2005 Of note this week • A Palestinian suicide bomber killed five and injured more than 50 Israelis at the entrance of a shopping mall in Netanya. A general closure was imposed on the oPt on 6 December. Barrier construction has started around Ma’ale Adumim settlement. 1. Physical Protection 1 Casualties 80 60 40 20 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 22 4 1 0 Israelis 60 5 0 2 Internationals 0000 • 30 November: One Palestinian minor aged 12 years old was injured in Jenin camp (Jenin) during and IDF search in the family’s house. • 30 November: Palestinians threw stones at the IDF who surrounded a house in Nablus city (Nablus). The IDF fired tear gas canisters and rubber coated metal bullets, injuring eight Palestinians. • 1 December: The IDF shot and injured one 23-year-old Palestinian during clashes with stone throwing Palestinians in Balata refugee camp (Nablus). • 2 December: Five Palestinians and one Israeli activist were injured by the IDF during a demonstration organized by Palestinians, international and Israeli activists against Barrier construction in Bil’in (Ramallah). • 2 December: Palestinians, international and Israeli activists demonstrated against the construction of the “special security arrangements” around Ofarim and Beit Arye settlements (Ramallah). -

12 July 2021

29 June - 12 July 2021 Latest developments (after the reporting period) • On 14 July, Israeli forces confiscated at least 49 structures in the Palestinian community of Ras al Tin, displacing 84 people, including 53 children. • On 15 July, Israeli forces in Humsa – Al Bqai’a confiscated a recently installed structure used to accommodate a family of eight, including six children, who had lost their previous home in last week’s incident (see below). Highlights from the reporting period • On 3 July, Israeli settlers, accompanied by soldiers, entered Qusra village, Nablus, and clashed with Palestinian residents, resulting in a Palestinian man, aged 21, killed. According to the military, the man threw an explosive device and Israeli forces shot him. Israeli settlers and Palestinian residents threw stones at each other and, according to local sources, after the Palestinian was shot, settlers beat him. In demonstrations where Palestinians called upon the Israeli authorities to return the body of the Palestinian killed, Israeli forces dispersed the crowd firing live ammunition, rubber bullets and tear gas, injuring several Palestinians. • Overall, Israeli forces injured at least 981 Palestinians, including 133 children, in clashes across the West Bank. Of those injured, 892 were in Nablus governorate, including in protests against settlement expansion in the villages of Beita and Osarin and in the abovementioned Qusra events; 19 were injured in Ras al ‘Amud and Silwan neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem; 13 in Halhul village (Hebron); and the rest in other locations. Overall, 36 Palestinians were shot by live ammunition, 214 by rubber bullets, and the rest were mainly treated for tear gas inhalation or were physically assaulted. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 05

U N I T E D N A T I O N S N A T I O N S U N I E S OCHA Weekly Report: 5 – 11 March 2008 | 1 OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org € Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 05 – 11 March 2008 Of note this week Gaza Strip: • 6 Palestinians were killed and 5 others were injured by the IDF in the Gaza Strip. • An IDF soldier was killed and 3 others were injured when Islamic Jihad members detonated a roadside bomb under an IDF jeep patrolling the eastern border of the Gaza Strip. • Following the attack on a Yeshiva (Jewish seminary) in West Jerusalem, armed Palestinians throughout the Gaza Strip took to the streets and opened fire in the air. Throughout these rallies, four injuries from stray bullets were reported. • Two demonstrations were organised to protest the IDF military operation in the Gaza. Strip. A further demonstration took place protesting against the Israeli siege of Gaza. • 28 home-made rockets and 35 mortar rounds were fired out of the Gaza Strip at Israel. According to Israeli media reports, one Israeli civilian was injured when a home-made rocket fired from north of Beit Hanoun, hit a building in Sderot. The IAF conducted 1 air- strike during the reporting period. West Bank: • 1 Palestinian was killed and 23 others were injured in direct conflict incidents in the West Bank.