George Gordon First Nations Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Bridge World

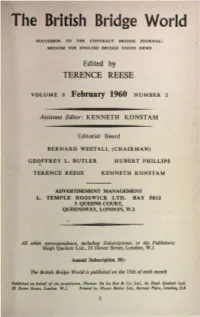

. '. - The British Bridge World SUCCESSOR TO THE CONTRACT BRIDGE JOURNAL: MEDIUM FOR ENGLISH BRIDGE UNION NEWS Edited by TERENCE REESE voLUME 9 February 1960 NUMBER 2 Assistant Editor: KENNETH KONSTAM Editorial Board BERNARD WE~TALL (CHAIRMAN) GEOFFREY L. BUTLER HUBERT PHILLIPS ~ TERENCE REESE KENNETH KONSTAM ADVERTISEMENT MANAGEMENT L. TEMPLE ROSSWICK LTD. BAY 5812 3 QUEENS COURT, QUEENSWAY, LONDON; W.2 All other correspondence, including Subscriptions, to the Publishers: Hugh Quekett Ltd., 35 Dover Street, London, W.l Annual Subscription 30/- The British Bridge World is published 011 the 15th of eaclz month Publlshtd on behalf of tht proprietors, Thomas De La Rut & Co. Ltd., by Hugh Qutktll Ltd. JS Dover Strttl, London JV.I. Print11d by llfoorc Batley Ltd., Rttreat Place, London. E.~ 3 February, !960 Contents Page Editorial 5-6 Bridge Forum 6 The Whitelaw Warriors, by George Baxter 7-10 Expected Entries for Olympiad at Turin ... 10 'Slamentable, by Harold Fra~klin ... ... 11-17 Yorkshire Wins Tollemache Cup, by Terence Reese . .. 19-21 · One Hundred Up: Repeat of January Prob~ems 22 . E.B. U. List of Secretaries ... 23 - Court of Sessions, by Alan Trusc<?tt . .. 24-27 Letter from Paris, by Jean Besse ... ... 27-29 · Subscription Form ... 29 You Say ... .. 30-31 Defending a Squeeze, by J. Hibbert . .. 32-34 One Hundred Up: February Competition . ... 34-35 One Hundred Up: Answers to January Problems . .. 36-42 Directory of E.B.U. Affiliated Clubs ... 43-44 Result of January Competition 44 E.B.U. Results ... 45-46 E.B.U. Master Points Register ... 47-48 Diary of Events 48 I • ·- 4 Editorial - •I BEFO!ffi THE STORM in soliciting, and being influenced Something of a lull this month, by, advice . -

Cass City Chronic^ * Volume 48, Number 32

NE sEc<iTo ONE SECTION ^ ^ "• *r^ ' ° **"3?f Eight Paces 1 M Ku-htt'ag^ ^j THIS ISSUE ^1 1 ^ M \4 THIS JSSUB 'Jj CASS CITY CHRONIC^ * VOLUME 48, NUMBER 32. CASS CITY, MICHIGAN. WEDNK8UAY, NOVKMHEK 85, l'J5;i. EIGHT PAGES.'1!1 From the 53 Cases Listed for IN OPLORATION Second Bad Chedk Questions Reveal Dilemma Editor's Corner December Court Term Passer Arrested Home, Selllool Council According to reports frum Hcj • ^^^^^^^_~|^^, Holds Knight of Chicajfi., wlms Kifty- three canes are listei o trull, Co-iiui'tiRTo, dib|u under tin In Tuscola County job is finding out these fiu-ts, th the circuit court calendar fi> iKinii! anil style uf Hnur ami Cut Notes Spa<?e Problems American publii: can e\ iwt t Tuscolu County for thu Dei-emlu' tivll vs. Ali« Wnlcislieri, iliiiniiws SL>o si'Vfi'al new gadgets on t term of tuurt, lndude.il are tw Autu-Owilt;i'ti InsimnK'i; Co., ; The need fur more space in the Cass City School sys- Tliu Tuscolu Cuimty Slieriff. market, Among them arc; an nil criminal cases, seven civil Jui-j Uumu-alic lii.s. Co., ami subroKin turn WHH Imiught into sharp focus Monday night by a group ceramic electric coffee maker, i n cases, 17 civil non-jury i-ases, 1 of Arnold tlrDimmill uml Clu>sh'> Dfimrlinuil umiaUtl UK anui. ported from Germany, '-• i ims i chancery cases and ID cases i of questions rehiled to -schix 1 problems presented to a panel bettor thu i'hivor; transpaivii which no progress has lu-en n ai aiul Cli.'sli.y MnDuiiKiill va. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

Saskatchewan Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9sk.1 of 29 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBEY SK AND BETWEEN ALIDA SK AND BETWEEN ANEROID SK AND LANCER SK 8 STORTHOAKS SK 10 EASTEND SK 82 SHACKLETON SK 8 BETWEEN ALLAN SK AND HAZENMORE SK 8 SWIFT CURRENT SK 62 BETHUNE -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Mannville Group of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Report 223 Industry and Resources Saskatchewan Geological Survey Jura-Cretaceous Success Formation and Lower Cretaceous Mannville Group of Saskatchewan J.E. Christopher 2003 19 48 Printed under the authority of the Minister of Industry and Resources Although the Department of Industry and Resources has exercised all reasonable care in the compilation, interpretation, and production of this report, it is not possible to ensure total accuracy, and all persons who rely on the information contained herein do so at their own risk. The Department of Industry and Resources and the Government of Saskatchewan do not accept liability for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies that may be included in, or derived from, this report. Cover: Clearwater River Valley at Contact Rapids (1.5 km south of latitude 56º45'; latitude 109º30'), Saskatchewan. View towards the north. Scarp of Middle Devonian Methy dolomite at right. Dolomite underlies the Lower Cretaceous McMurray Formation outcrops recessed in the valley walls. Photo by J.E. Christopher. Additional copies of this digital report may be obtained by contacting: Saskatchewan Industry and Resources Publications 2101 Scarth Street, 3rd floor Regina, SK S4P 3V7 (306) 787-2528 FAX: (306) 787-2527 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended Citation: Christopher, J.E. (2003): Jura-Cretaceous Success Formation and Lower Cretaceous Mannville Group of Saskatchewan; Sask. Industry and Resources, Report 223, CD-ROM. Editors: C.F. Gilboy C.T. Harper D.F. Paterson RnD Technical Production: E.H. Nickel M.E. Opseth Production Editor: C.L. Brown Saskatchewan Industry and Resources ii Report 223 Foreword This report, the first on CD to be released by the Petroleum Geology Branch, describes the geology of the Success Formation and the Mannville Group wherever these units are present in Saskatchewan. -

Minjimendaamowinon Anishinaabe

Minjimendaamowinon Anishinaabe Reading and Righting All Our Relations in Written English A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Department of English. University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Janice Acoose / Miskwonigeesikokwe Copyright Janice Acoose / Miskwonigeesikokwe January 2011 All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, whole or in part, may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan i ABSTRACT Following the writing practice of learned Anishinaabe Elders Alexander Wolfe (Benesih Doodaem), Dan Musqua (Mukwa Doodaem) and Edward Benton-Banai (Geghoon Doodaem), this Midewiwin-like naming Manidookewin acknowledges Anishinaabe Spiritual teachings as belonging to the body of Midewiwin knowledge. -

August 15, 1899

x J -, •• %ufi ; •*£. i * ;r \ ’ ESTABLISHED JUNE 23,. 180g-VOL. 38. PORTLAND, MAINE, TUESDAY MORNINQ, AUGUST IS, 1899. ISBS.tVgSSI PRICE THREE CENTS, the sufferer* tbe by atorm In Porto Biro, muscles enveloping tbe vertebral left her at the foot of column APPEAL TO tiOmOKS. pier PaulUo street, most, maintain at 4,10 II. LABORI STILL ALIVE. They however, today, FIRE AT PEAKS ISLAND. Brooklyn o'clock this afternoon. full reserve the I TERRIBLE EXPERIENCE. About respecting Integrity of STRUCK drugs fflfiOJ. two-thirds o» the original cargo of the Inng and spinal orod." army eoppllea waa left behind to make The bulletin Is signed by four loom for the of doctors, qunntlilee rloe, beans, Bensnd, Belobla, Brlsaauds and Vldsl Rnrned grain, eto. Cottage To Gronntl This clothing, lumber, required and It Is timed at 8.89 o'clock this morn- for tbe Immediate necessity of the Funds Needed For Porto sufferer*. Latest Bulletin ing. Morning. Up to within a quarter of an hour of Reports Mr. A. R. Stubbs Broke Collision on Yarmouth sailing voluntary donations kept piling Tbe attempt made upon the life of M. Rican Sufferers. In. r Labor! was tha It_1* spotted that Han Juan will be Improvement. evidently result of a plot. His ft Wm In the Vicinity of the Innei reached not later than A letter waa sent to tbe of Leg Electrics. Friday night. oomralssary Holier police this morning, warning him that fllced Department Seemed SARGENT it waa Intended to make an attempt Able To Handle It All Right. ARRESTED. upon the life of General Meroler. -

Press Packet

One Arrow Equestrian One Arrow First Nation proudly announces Centre’s EAL Four Good Reasons Cover this Event 1) THE LEADING, First Nation COMMUNITY (nationally and internationally) to offer a personal growth and development program for every youth in the community to participate in, delivered through the school; a ground breaking commitment to the overall wellness to One Arrow First Nation. One Arrow EAL Directors will be on-site and available for interviews June 9th, at 11:30 a.m. 2) EAL RESEARCH PARTNERSHIP, AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF THE CONTRIBUTION OF EQUINE ASSISTED LEARNING IN THE WELLBEING OF FIRST NATIONS PEOPLE LIVING ON RESERVE; The study is a collaborative effort between the One Arrow Equestrian Ctr (offers EAL Program), researchers at Brandon University (School of Health Studies), Almightyvoice Educational Centre (educational partnership and support), One Arrow First Nation of Saskatchewan (Chief and Council providing full support). Press Packet Researcher from BU, EAL Dirs, School Principal, and One Arrow First Nation Special Education Dir will be on-site and available for interviews, at 11:30 a.m. 3) ONE ARROW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GRAND One Arrow Equestrian Centre OPENING and Inspire Direction Equine Assisted I.D.E.A.L. Program Learning Program (I.D.E.A.L.), first program of its kind, Inspire Direction Equine Assisted Learning designed to facilitate new skills for personal growth and Box 89, Domremy, SK S0K1G0 development: four teachers and their students will be Lawrence Gaudry – Executive Director, 306.423.5454 demonstrating different EAL exercises in the arena Koralie Gaudry – Program Director, 306.233.8826 www.oaecidealprogram.ca E-mail: [email protected] between 12:00 - 3:00 p.m. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ...............................................................................................................................................