MAS439 Commutative Algebra and Algebraic Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modules with Artinian Prime Factors

PROCEEDINGS of the AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 78, Number 3. March 1980 MODULES WITH ARTINIAN PRIME FACTORS EFRAIM P. ARMENDARIZ Abstract. An R -module M has Artinian prime factors if M/PM is an Artinian module for each prime ideal P of R. For commutative rings R it is shown that Noetherian modules with Artinian prime factors are Artinian. If R is either commutative or a von Neumann regular K-rmg then the endomorphism ring of a module with Artinian prime factors is a strongly ir-regular ring. A ring R with 1 is left ir-regular if for each a G R there is an integer n > 1 and b G R such that a" = an+lb. Right w-regular is defined in the obvious way, however a recent result of F. Dischinger [5] asserts the equivalence of the two concepts. A ring R is ir-regular if for any a G R there is an integer n > 1 and b G R such that a" = a"ba". Any left 7r-regular ring is 77-regular but not con- versely. Because of this, we say that R is strongly ir-regular if it is left (or right) w-regular. In [2, Theorem 2.5] it was established that if R is a (von Neumann) regular ring whose primitive factor rings are Artinian and if M is a finitely generated R-module then the endomorphism ring EndÄ(Af ) of M is a strongly 77-regular ring. Curiously enough, the same is not true for finitely generated modules over strongly w-regular rings, as Example 3.1 of [2] shows. -

Gsm073-Endmatter.Pdf

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/gsm/073 Graduat e Algebra : Commutativ e Vie w This page intentionally left blank Graduat e Algebra : Commutativ e View Louis Halle Rowen Graduate Studies in Mathematics Volum e 73 KHSS^ K l|y|^| America n Mathematica l Societ y iSyiiU ^ Providence , Rhod e Islan d Contents Introduction xi List of symbols xv Chapter 0. Introduction and Prerequisites 1 Groups 2 Rings 6 Polynomials 9 Structure theories 12 Vector spaces and linear algebra 13 Bilinear forms and inner products 15 Appendix 0A: Quadratic Forms 18 Appendix OB: Ordered Monoids 23 Exercises - Chapter 0 25 Appendix 0A 28 Appendix OB 31 Part I. Modules Chapter 1. Introduction to Modules and their Structure Theory 35 Maps of modules 38 The lattice of submodules of a module 42 Appendix 1A: Categories 44 VI Contents Chapter 2. Finitely Generated Modules 51 Cyclic modules 51 Generating sets 52 Direct sums of two modules 53 The direct sum of any set of modules 54 Bases and free modules 56 Matrices over commutative rings 58 Torsion 61 The structure of finitely generated modules over a PID 62 The theory of a single linear transformation 71 Application to Abelian groups 77 Appendix 2A: Arithmetic Lattices 77 Chapter 3. Simple Modules and Composition Series 81 Simple modules 81 Composition series 82 A group-theoretic version of composition series 87 Exercises — Part I 89 Chapter 1 89 Appendix 1A 90 Chapter 2 94 Chapter 3 96 Part II. AfRne Algebras and Noetherian Rings Introduction to Part II 99 Chapter 4. Galois Theory of Fields 101 Field extensions 102 Adjoining -

Lectures on Non-Commutative Rings

Lectures on Non-Commutative Rings by Frank W. Anderson Mathematics 681 University of Oregon Fall, 2002 This material is free. However, we retain the copyright. You may not charge to redistribute this material, in whole or part, without written permission from the author. Preface. This document is a somewhat extended record of the material covered in the Fall 2002 seminar Math 681 on non-commutative ring theory. This does not include material from the informal discussion of the representation theory of algebras that we had during the last couple of lectures. On the other hand this does include expanded versions of some items that were not covered explicitly in the lectures. The latter mostly deals with material that is prerequisite for the later topics and may very well have been covered in earlier courses. For the most part this is simply a cleaned up version of the notes that were prepared for the class during the term. In this we have attempted to correct all of the many mathematical errors, typos, and sloppy writing that we could nd or that have been pointed out to us. Experience has convinced us, though, that we have almost certainly not come close to catching all of the goofs. So we welcome any feedback from the readers on how this can be cleaned up even more. One aspect of these notes that you should understand is that a lot of the substantive material, particularly some of the technical stu, will be presented as exercises. Thus, to get the most from this you should probably read the statements of the exercises and at least think through what they are trying to address. -

Lectures on Local Cohomology

Contemporary Mathematics Lectures on Local Cohomology Craig Huneke and Appendix 1 by Amelia Taylor Abstract. This article is based on five lectures the author gave during the summer school, In- teractions between Homotopy Theory and Algebra, from July 26–August 6, 2004, held at the University of Chicago, organized by Lucho Avramov, Dan Christensen, Bill Dwyer, Mike Mandell, and Brooke Shipley. These notes introduce basic concepts concerning local cohomology, and use them to build a proof of a theorem Grothendieck concerning the connectedness of the spectrum of certain rings. Several applications are given, including a theorem of Fulton and Hansen concern- ing the connectedness of intersections of algebraic varieties. In an appendix written by Amelia Taylor, an another application is given to prove a theorem of Kalkbrenner and Sturmfels about the reduced initial ideals of prime ideals. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Local Cohomology 3 3. Injective Modules over Noetherian Rings and Matlis Duality 10 4. Cohen-Macaulay and Gorenstein rings 16 d 5. Vanishing Theorems and the Structure of Hm(R) 22 6. Vanishing Theorems II 26 7. Appendix 1: Using local cohomology to prove a result of Kalkbrenner and Sturmfels 32 8. Appendix 2: Bass numbers and Gorenstein Rings 37 References 41 1. Introduction Local cohomology was introduced by Grothendieck in the early 1960s, in part to answer a conjecture of Pierre Samuel about when certain types of commutative rings are unique factorization 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 13C11, 13D45, 13H10. Key words and phrases. local cohomology, Gorenstein ring, initial ideal. The first author was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation, DMS-0244405. -

Certain Artinian Rings Are Noetherian

Can. J. Math., Vol. XXIV, No. 4, 1972, pp. 553-556 CERTAIN ARTINIAN RINGS ARE NOETHERIAN ROBERT C. SHOCK 1. Introduction. Throughout this paper the word "ring" will mean an associative ring which need not have an identity element. There are Artinian rings which are not Noetherian, for example C(pco) with zero multiplication. These are the only such rings in that an Artinian ring R is Noetherian if and only if R contains no subgroups of type C(pœ) [1, p. 285]. However, a certain class of Artinian rings is Noetherian. A famous theorem of C. Hopkins states that an Artinian ring with an identity element is Noetherian [3, p. 69]. The proofs of these theorems involve the method of "factoring through the nilpotent Jacobson radical of the ring". In this paper we state necessary and sufficient conditions for an Artinian ring (and an Artinian module) to be Noetherian. Our proof avoids the concept of the Jacobson radical and depends primarily upon the concept of the length of a composition series. As a corollary we obtain the result of Hopkins. All conditions are on the right, that is, an Artinian ring means a right Artinian ring, etc. We say a module A is embeddable in a module B provided that A is isomorphic to some submodule of B. Our Theorem 3 states that an Artinian ring R is Noetherian if and only if a cyclic Noetherian submodule ofR is embeddable in some Noetherian factor module of R. An example in the paper shows that in an Artinian ring R which is also Noetherian, a cyclic submodule need not be isomorphic to some factor module of R. -

Artinian Modules and Modules of Which All Proper Submodules Are Finitely Generated

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNAL OF ALGEBRA 95, 201-216 (1985) Artinian Modules and Modules of Which All Proper Submodules Are Finitely Generated WILLIAM HEINZER Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 AND DAVID LANTZ Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, and Colgate University, Hamilton, New York 13346 Communicated by I. N. Herstein Received September 5, 1983 1. INTRODUCTION William D. Weakley, in [Wl], studied modules (unitary, over a com- mutative ring with unity) which are not finitely generated but all of whose proper submodules are finitely generated. Weakley called such modules “almost finitely generated” (a.f.g.). He noted that an a.f.g. module has prime annihilator and that, as a faithful module over a domain, it is either torsion or torsion-free. If torsion-free, it is isomorphic as a module to the domain’s quotient field. If torsion, it is Artinian, so Weakley was led to the tools of study of Artinian modules developed by Matlis [Ml, M23 and Vamos [V]. These tools include, for a quasilocal ring (R, M), the injective envelope E,(R/M) of the residue field R/M. The purpose of the present paper is to combine results of [Wl] and [GH2] to characterize the form of a.f.g. modules and the rings which admit such modules, and to describe the a.f.g. submodules of E,(R/M). In Section 2, we refine a result of [ Wl ] to conclude that, if R is a domain and (F’, P) is a discrete rank one valuation domain between R and its quotient field K, then K/V is an a.f.g. -

On the Noetherian Dimension of Artinian Modules*

Vietnam Journal o! Mathematics3O:2 (2002) 121-130 V [,e r[rma nm _J[o,rurrrrm a l[ olP Mt,A.]f lHI]EMt,A.]f ]IC S O NCST2OO2 On the Noetherian Dimension of Artinian Modules* Nguyen T\r Cuong and Le Thanh Nhan Institute of Mathemati,cs.P. O. Bor 631, Bo Ho, Hanoi, V'ietnam ReceivedJuly L4, 2000 Abstract. Somenew resultsof Noetheriandimension of Artinian modulesare given and severalproperties of Noetherian dimension of local cohomologymodules of finitely generatedmodules are shown. After giving an exampleof an Artinian module ,4 which has Krull dimension strictly larger than its Noetherian dimension, we present some sufficient conditions on Artinian modules .A such that the both notions of dimension of ,4 are the same. 1".Introduction The concept of Krull dimension for Artinian modules was introduced by Roberts lI2]. Kirby [7] changed the terminology of Roberts and referred to Noethe- rian dimension (N-dim) to avoid any confusion with Krull dimension defined for finitely generated modules. In this note we use the terminology of Kirby [7]. Many properties of Noetherian dimension of Artinian modules have been given in [3,7, L2,l7l. The purpose of this note is to study Noetherian dimension of Artinian modules. Expecially, we prove some results on Noetherian dimension of local cohomology modules when these modules are Artinian. This paper is divided into 4 sections. In Sec.2 we will give some preliminary results on Noetherian dimension of Artinian modules. Let R be a commuta- tive Noetherian ring, A an Artinian rR-module and M a finitely generated R- module. -

Commutative Algebra

Version of September 3, 2012 A Term of Commutative Algebra By Allen ALTMAN and Steven KLEIMAN Contents Preface . iii 1. Rings and Ideals ................... 1 2. Prime Ideals .................... 6 3. Radicals ...................... 10 4. Modules ...................... 14 5. Exact Sequences ................... 20 6. Direct Limits .................... 26 7. Filtered Direct Limits . 33 8. Tensor Products ................... 37 9. Flatness ...................... 43 10. Cayley{Hamilton Theorem . 49 11. Localization of Rings . 55 12. Localization of Modules . 61 13. Support ..................... 66 14. Krull{Cohen{Seidenberg Theory . 71 15. Noether Normalization . 75 Appendix: Jacobson Rings . 80 16. Chain Conditions . 82 17. Associated Primes . 87 18. Primary Decomposition . 91 19. Length ...................... 97 20. Hilbert Functions . 101 Appendix: Homogeneity . 107 21. Dimension . 109 22. Completion . 115 23. Discrete Valuation Rings . 122 24. Dedekind Domains . 127 25. Fractional Ideals . 131 26. Arbitrary Valuation Rings . 136 Solutions . 141 1. Rings and Ideals . 141 2. Prime Ideals . 143 3. Radicals . 145 4. Modules . 148 5. Exact Sequences . 149 i 6. Direct Limits . 153 7. Filtered direct limits . 156 8. Tensor Products . 158 9. Flatness . 159 10. Cayley{Hamilton Theorem . 161 11. Localization of Rings . 164 12. Localization of Modules . 167 13. Support . 168 14. Krull{Cohen{Seidenberg Theory . 171 15. Noether Normalization . 174 16. Chain Conditions . 177 17. Associated Primes . 179 18. Primary Decomposition . 180 19. Length . 183 20. Hilbert Functions . 185 21. Dimension . 188 22. Completion . 190 23. Discrete Valuation Rings . 193 24. Dedekind Domains . 197 25. Fractional Ideals . 199 26. Arbitrary Valuation Rings . 200 References . 202 Index . 203 ii Preface There is no shortage of books on Commutative Algebra, but the present book is different. -

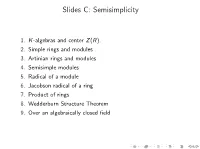

Slides C: Semisimplicity

Slides C: Semisimplicity 1. K-algebras and center Z(R). 2. Simple rings and modules 3. Artinian rings and modules 4. Semisimple modules 5. Radical of a module 6. Jacobson radical of a ring 7. Product of rings 8. Wedderburn Structure Theorem 9. Over an algebraically closed field Noncommutative rings and algebras We now return to noncommutative (but associative and unital) rings. We normally take right R-modules. Then an R-module homomorphism f : M ! N satisfies: f (xr) = f (x)r which is an \associativity rule". A left R-module is the same as a right Rop-module where Rop is the opposite ring of R with order of multiplication reversed: ab in Rop is ba in R. Definition. For K a field, a K-algebra is ring A which is also a K-module (vector space over K) so that addition is K-linear and multiplication is K-bilinear. K-algebra and center Z(R) Definition. The center Z(R) of a ring R is the set of all z 2 R which commutes with all elements of R. E.g., 0; 1 2 Z(R). Z(R) := fz 2 R j rz = zr 8r 2 Rg Proposition 1.1. Z(R) is a subring of R. Proposition 1.2. For K a field, R is a K-algebra , K ⊆ Z(R) Simple rings Definition. A ring is simple if it has no nontrivial 2-sided ideals. Examples. I Fields are simple rings. I A division ring D is simple: A division ring is a ring in which every nonzero element has an inverse. -

6. Artinian and Noetherian Modules 6.1. Definitions and Elementary Properties. a Module Is Artinian (Respec- Tively Noetherian)

6. Artinian and Noetherian modules [s:anmod] [ss:anmoddef] 6.1. Definitions and elementary properties. A module is Artinian (respec- tively Noetherian) if it satisfies either of the following equivalent conditions: • every non-empty collection of submodules contains a minimal (repsectively maximal) element with respect to inclusion. • any descending (respectively ascending) chain of submodules stabilises. A module is Artinian (respectively Noetherian) if and only if it is so over its ring of homotheties. An infinite direct sum of non-zero modules is neither Artinian nor Noetherian. A vector space is Artinian (respectively Noetherian) if and only if its dimension is finite. We now list some elementary facts about Artinian and Noetherian modules. The following would continue to be true if we replaced ‘Artinian’ by ‘Noetherian’: • Submodules and quotient modules of Artinian modules are Artinian. • If a submodule N of a module M and the quotient M/N by it are Artinian, then so is M. • A finite direct sum is Artinian if and only if each of the summands is so. A comment about the simultaneous presence of the both conditions: • A module is both Artinian and Noetherian if and only if it has finite length. Pertaining to the Noetherian condition alone, we make two more observations: • Any subset S of a Noetherian module contains a finite subset that generates the same submodule as S. • A module is Noetherian if and only if every submodule of it is finitely generated. [s:fittingkrs] 6.2. Decomposition into indecomposables of a finite length module. Let u be an endomorphism of a module M. -

Part III — Algebras

Part III | Algebras Based on lectures by C. J. B. Brookes Notes taken by Dexter Chua Lent 2017 These notes are not endorsed by the lecturers, and I have modified them (often significantly) after lectures. They are nowhere near accurate representations of what was actually lectured, and in particular, all errors are almost surely mine. The aim of the course is to give an introduction to algebras. The emphasis will be on non-commutative examples that arise in representation theory (of groups and Lie algebras) and the theory of algebraic D-modules, though you will learn something about commutative algebras in passing. Topics we discuss include: { Artinian algebras. Examples, group algebras of finite groups, crossed products. Structure theory. Artin{Wedderburn theorem. Projective modules. Blocks. K0. { Noetherian algebras. Examples, quantum plane and quantum torus, differen- tial operator algebras, enveloping algebras of finite dimensional Lie algebras. Structure theory. Injective hulls, uniform dimension and Goldie's theorem. { Hochschild chain and cochain complexes. Hochschild homology and cohomology. Gerstenhaber algebras. { Deformation of algebras. { Coalgebras, bialgebras and Hopf algebras. Pre-requisites It will be assumed that you have attended a first course on ring theory, eg IB Groups, Rings and Modules. Experience of other algebraic courses such as II Representation Theory, Galois Theory or Number Fields, or III Lie algebras will be helpful but not necessary. 1 Contents III Algebras Contents 0 Introduction 3 1 Artinian algebras 6 1.1 Artinian algebras . .6 1.2 Artin{Wedderburn theorem . 13 1.3 Crossed products . 18 1.4 Projectives and blocks . 19 1.5 K0 ................................... 27 2 Noetherian algebras 30 2.1 Noetherian algebras . -

Theory of Rings

Theory of Rings Farid Aliniaeifard Contents 1 Categories1 1.1 Categories.....................................1 2 Commutative Rings and Modules2 2.1 Chain Condition.................................2 2.2 Prime and Primary Ideals............................5 2.3 Primary Decomposition.............................8 2.4 Noetherian Rings and Modules......................... 12 2.5 Dedekind Domains................................ 15 2.6 The Hilbert Nullstellensatz............................ 18 3 The structure of rings 22 3.1 Simple and primitive rings............................ 22 3.2 The Jacobson Radical.............................. 29 3.3 Semisimple Rings................................. 36 1 Abstract Where does the name "ring" come from? Here what I found in stackexchange webpage at https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/61497/why-are-rings-called-rings: The name "ring" is derived from Hilbert's term "Zahlring" (number ring), introduced in his Zahlbericht for certain rings of algebraic integers. As for why Hilbert chose the name "ring", I recall reading speculations that it may have to do with cyclical (ring-shaped) behavior of powers of algebraic integers. Namely, if α is an algebraic integer of degree n then αn is a Z-linear combination of lower powers of α, thus so too are all higher powers of α. Hence all powers cycle back onto 1; α; ··· ; αn−1, i.e. Z[α] is a finitely generated Z-module. Possibly also the motivation for the name had to do more specifically with rings of cyclotomic integers. In this course we start with category theory and then dive into the category of rings, and this category we first study commutative rings and modules, and then we talk about structure of rings and we will see the structures of semisimple rings, prime and semiprime rings, Algebras and devision algebras.