Looking for the Good in Garbage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Graduation Exercises Will Be Official

TheMONDAY, Graduation MAY THE EIGHTEENTH Exercises TWO THOUSAND AND FIFTEEN NINE O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING THOMAS K. HEARN, JR. PLAZA THE CARILLON: “Mediation from Thaïs” . Jules Massenet Raymond Ebert (’60), University Carillonneur William Stuart Donovan (’15), Student Carillonneur THE PROCESSIONAL . Led by Head Faculty Marshals THE OPENING OF COMMENCEMENT . Nathan O . Hatch President THE PRAYER OF INVOCATION . The Reverend Timothy L . Auman University Chaplain REMARKS TO THE GRADUATES . President Hatch THE CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES . Rogan T . Kersh Provost Carlos Brito, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Charles L . Iacovou, Dean, School of Business Stephen T . Colbert, Doctor of Humane Letters Sponsor: Michele K . Gillespie, Dean-Designate, Wake Forest College George E . Thibault, Doctor of Science Sponsor: Peter R . Lichstein, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine Jonathan L . Walton, Doctor of Divinity Sponsor: Gail R . O'Day, Dean, School of Divinity COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS . Stephen Colbert Comedian and Late Night Television Host THE HONORING OF RETIRING FACULTY FROM THE REYNOLDA CAMPUS Bobbie L . Collins, M .S .L .S ., Librarian Ronald V . Dimock, Jr ., Ph .D ., Thurman D. Kitchin Professor of Biology Jack D . Ferner, M .B .A ., Lecturer of Management J . Kendall Middaugh, II, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Management James T . Powell, Ph .D ., Associate Professor of Classical Languages David P . Weinstein, Ph .D ., Professor of Politics and International Affairs FROM THE MEDICAL CENTER CAMPUS James D . Ball, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology William R . Brown, Ph .D ., Professor Emeritus of Radiology Frank S . Celestino, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Family and Community Medicine Wesley Covitz, M .D ., Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics Robert L . -

Gunsmoke" As Broadcast

REPLAY FORMAT 3/12/55 p L&MFILTERS, ATTACHED Present "GUNSMOKE" AS BROADCAST "KITE; I S REWARD " x`36 SATURDAY - FJUARY 19, 1955 PRE-CUT 3 : 30 PM - 4 :00 PM PST SATURDAY - MARCH 5, 1955 AIR 5 :00 PM - 5 :28:50 PM PST SATURDAY - MARCH 12, 1955 REPLAY 9 :30 AM - 9 :59 :30 AM PST DIRECTOR : NORMAN MACDONNELL SATURDAY - FEBflUARY 19, 195 5 ASSOCIATE : KENNY MCMANUS CAST. : 11 :00 AM - 1 :30 PM ASSOCIATE : ENGINEER : BOB CHADWICK ENGINEER : and SOUND : 2 :30 PM - 3 :30 PM SOUND : RAY KEMPER TOM HANLEY MUSIC : 1 :30 PM - 3 :30 P M MUSIC : R KOURY STUDIO #1 ANNOUNCER : , GEORGE WALSH AUTHOR : JOHN ASTON AMPLx 3 :15 PM - 4 :00 P M WILLIAM CONRA D as MATT DILLO N CHESTER . Parley Baer KITTY . Georgia Elli s DOC . Howard McNear KITE . John Dehner ANDY . Sam Edwards BAR . & Is Joe Duva l JAII Vic Perri n DH LIG 0382530 L&MFTLTERS Present GUNSMOKE SATURDAY. MARCH 5 , 1955 5:00-5 :28 :50 PM PST 1 SOUND : HORSE FADES ON TO FULL MIKE . .O N CUE : RECORDED SHOT 2 MUSIC ; HOLD UNDER . .TRACK 1 3 WALSH ; GUNSMOKE . .brought to you by L & M Alters, This is it ; 4 L & M is best - stands out from all the rest l 5 MU SIC : FIGURE AND UNDER . TRACK 2 6 WALSH : Around Dodge City and in the territory on West - there's 7 just one way to handle the killers and the spoilers - and 8 that's with a U .S . Marshal and the smell of - GUNSMOI2 1 9 MUSIC : THEME HITS : FULL ROAD SWTEP AND UNDER . -

Fact Or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News

FACT OR FICTION: HOLLYWOOD LOOKS AT THE NEWS Loren Ghiglione Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University Joe Saltzman Director of the IJPC, associate dean, and professor of journalism USC Annenberg School for Communication Curators “Hollywood Looks at the News: the Image of the Journalist in Film and Television” exhibit Newseum, Washington D.C. 2005 “Listen to me. Print that story, you’re a dead man.” “It’s not just me anymore. You’d have to stop every newspaper in the country now and you’re not big enough for that job. People like you have tried it before with bullets, prison, censorship. As long as even one newspaper will print the truth, you’re finished.” “Hey, Hutcheson, that noise, what’s that racket?” “That’s the press, baby. The press. And there’s nothing you can do about it. Nothing.” Mobster threatening Hutcheson, managing editor of the Day and the editor’s response in Deadline U.S.A. (1952) “You left the camera and you went to help him…why didn’t you take the camera if you were going to be so humane?” “…because I can’t hold a camera and help somebody at the same time. “Yes, and by not having your camera, you lost footage that nobody else would have had. You see, you have to make a decision whether you are going to be part of the story or whether you’re going to be there to record the story.” Max Brackett, veteran television reporter, to neophyte producer-technician Laurie in Mad City (1997) An editor risks his life to expose crime and print the truth. -

Amy Renee Leiker Writing Portfolio

Amy Renee Leiker Portfolio Writing Amy Renee Leiker Website: http://amyreneeleiker.com Twitter: @amyreneeleiker E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 316-305-2505 Table of Contents About Me Portfolio Journalism Résumé Newspaper Clips: Feature Articles Newspaper Clips: News Articles Writing Contact Information About Me Since January 2011, I’ve dedicated a slice of my life each week to reporting, writing and learning the ropes (translation: how to trick the computer system into working) at The Wichita Eagle in Wichita, Kan., where I’m an intern. In that time, I’ve been inspired by a mom whose 5-year-old boy, by all rights, should have died at birth. I’ve watched another mother weep over the sweet, autistic son she lost in a drowning accident in 2010. I flew in a fully restored WWII B-24 bomber, and I’m terrified of heights. I’ve reported from the scene of a murder-suicide; a stabbing among high school girls (the cops called it an ongoing feud); a rollover accident where a conscious semi driver jackknifed his truck to block traffic -- he saved the lives of two motorcyclists, a state trooper told me, who laid their bike down to avoid being crushed by a car. Once, a thick-knee bird with an unnatural attraction to humans attacked my jeans at the Sedgwick County Zoo. I’ve sunk knee-deep in mud at a dried- up Butler County Lake. I’ve seen dogs tracking humans, a church service at Cheney Lake and a solider meet his 3-month-old son for the first time. -

Conyers Old Time Radio Presents the Scariest Episodes of OTR

Conyers Old Time Radio Presents the Scariest Episodes of OTR Horror! Playlist runs from ~6:15pm EDT October 31st through November 4th (playing twice through) War of the Worlds should play around 8pm on October 31st!! _____________________________________________________________________________ 1. OTR Horror ‐ The Scariest Episodes Of Old Time Radio! Fear You Can Hear!! (1:00) 2. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 Introduction To Horror (2:01) 3. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 The Dark (8:33) 4. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 Chicken Heart (7:47) 5. Quiet Please ‐ 480809 (060) The Thing On The Fourble Board (23:34) 6. Escape ‐ 491115 (085) Three Skeleton Key starring Elliott Reid, William Conrad, and Harry Bartell (28:50) 7. Suspense ‐ 461205 (222) House In Cypress Canyon starring Robert Taylor and Cathy Lewis (30:15) 8. The Mercury Theatre On The Air ‐ 381030 (17) The War Of The Worlds starring Orson Welles (59:19) 9. Fear on Four ‐ 880103 (01) The Snowman Killing (28:41) 10. Macabre ‐ 620108 (008) The Edge of Evil (29:47) 11. Nightfall ‐ 800926 (13) The Repossession (30:49) 12. CBS Radio Mystery Theater ‐ 740502 (0085) Dracula starring Mercedes McCambridge (44:09) 13. Suspense ‐ 550607 (601) Mary Shelley's Frankenstein starring Stacy Harris and Herb Butterfield (24:27) 14. Mystery In The Air ‐ 470814 (03) The Horla starring Peter Lorre (29:49) 15. The Weird Circle ‐ 450429 (74) Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (27:20) 16. The Shadow ‐ 430926 (277) The Gibbering Things starring Bret Morrison and Marjorie Anderson (28:24) 17. Lights Out ‐ 470716 (002) Death Robbery starring Boris Karloff (29:16) 18. -

THE WHISTLER: Notes on Murder Simpson, Tom Brown, Britt Wood, Jeanne Bates, Lawrence Dobkin

Project1:8 Page Booklet 4/30/08 2:24 PM Page 1 Julie from the plan but his actions set his plan spinning out of control. With Bill Forman, Lamont Johnson, Gloria Ann THE WHISTLER: Notes on Murder Simpson, Tom Brown, Britt Wood, Jeanne Bates, Lawrence Dobkin. Program Guide by Jim Widner CD 10A - “Final Papers” – 8/24/1952 – Anna Craig, a European immigrant with a shady past, has gotten the news On May 16th, 1942 a new mystery that she will soon become a citizen. Immigration lawyer, program called The Whistler aired over Stanley Craig is Anna’s husband and knows nothing of her the Columbia Broadcasting System’s past. Lisa Felder, another immigrant with a shady past, West Coast network. The stories for the threatens to reveal Anna’s past unless she convinces her husband to take on her case. Fearful, Anna poisons Lisa rather series were anthologized morality plays than succumb to the threat. When Stanley tells Anna he has to about everyday individuals caught in a go to Europe to investigate Lisa’s past, Anna decides to kill her web of their own making, and tripped up husband to avoid his discovering her own past but her methods by a twist of fate in the end. Heard soon reveal her crimes. With Bill Forman, Gail Bonney, throughout each radio play, as the events William Conrad Gladys Holland, Joseph Kearns, John Stevenson. became a tangled web of crime, was a shadowy voice-of-fate. Dripping with CD 10B - “The Secret of Chalk Point” – 9/7/1952 – Kay Fowler, staying at the Yaeger House at sarcasm, it preached to listeners about the Chalk Point meets a young man on the beach during a heavy fog who says he is the husband of old futility of the criminal act they’d just Mrs. -

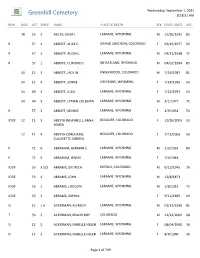

Greenhill Web Listing

Wednesday, September 1, 2021 Greenhill Cemetery 8:18:31 AM ROW BLOC LOT SPACE NAME PLACE OF DEATH SEX DEATH_DATE AGE 78 55 2 AALTO, EVOR J LARAMIE, WYOMING M 12/26/1995 85 R 57 4 ABBOTT, ALICE E. GRAND JUNCTION, COLORADO F 03/15/1977 66 R 57 2 ABBOTT, ALLEN C. LARAMIE, WYOMING M 04/11/1938 71 R 57 1 ABBOTT, CLIFFORD J. WHEATLAND, WYOMING M 04/02/1994 85 34 12 3 ABBOTT, JACK W. ENGLEWOOD, COLORADO M 7/26/1987 81 34 12 4 ABBOTT, JENNIE CHEYENNE, WYOMING F 7/24/1959 54 34 49 4 ABBOTT, JULIA LARAMIE, WYOMING F 7/21/1957 54 34 49 3 ABBOTT, LYMAN COLEMAN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 3/1/1977 71 R 57 3 ABBOTT, MINNIE LARAMIE, WYOMING F 2/9/1932 54 IOOF 12 11 3 ABEYTA (MUNNELL), ANNA BOULDER, COLORADO F 12/26/2003 53 MARIA 12 11 4 ABEYTA-CORCHADO, BOULDER, COLORADO F 7/13/2006 56 CLAUDETTE ANDREA P 72 6 ABRAHAM, HERMAN E. LARAMIE, WYOMING M 2/3/1962 84 P 72 5 ABRAHAM, JENNIE LARAMIE, WYOMING F 7/4/1948 IOOF 53 3 1/2 ABRAMS, DIETRICH PUEBLO, COLORADO M 9/12/1945 76 IOOF 53 4 ABRAMS, JOHN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 11/8/1873 IOOF 53 1 ABRAMS, LUDOLPH LARAMIE, WYOMING M 1/8/1913 72 IOOF 53 2 ABRAMS, SOPHIA F 9/12/1895 49 O 12 1 A ACKERMAN, ALFRED F LARAMIE, WYOMING M 01/13/1996 81 T 56 5 ACKERMAN, EDWIN ROY COLORADO M 11/22/2002 68 O 12 2 ACKERMAN, ISABELLE HELEN LARAMIE, WYOMING F 08/04/1960 36 O 12 2 ACKERMAN, ISABELLE HELEN LARAMIE, WYOMING F 8/4/1960 36 Page 1 of 749 ROW BLOC LOT SPACE NAME PLACE OF DEATH SEX DEATH_DATE AGE L 66 5 ACKERMAN, JACK ALLEN LARAMIE, WYOMING M 7/4/1970 20 T 56 8 ACKERMAN, ROY FRANCIS LARAMIE, WYOMING M 2/27/1936 51 O 12 1 ACKERMAN, RUDOLPH LARAMIE, WYOMING M 10/10/1951 35 HENRY O 60 2 ACKERSON, JAMES R. -

Temple Houston

by Glenn A. Mosley In the middle of July 1963, actor Jeffrey Hunter had reason to feel upbeat. For one thing, he and his family were vacationing in Acapulco. For another, things seemed right in his acting career as well. Director John Ford had just hired Hunter as the fifth star of Ford's new Western, The Long Flight (released as Cheyenne Autumn). He'd join a cast that already included James Stewart and Richard Widmark in what would be his fourth film with the great director. That news had come on the heels of an announcement from Warner Brothers that Hunter had signed a long term contract for film and television work, beginning with a television Western pilot shot that March, Temple Houston. The pilot focused on the exploits of lawyer Temple Houston, son of famed Texan Sam Houston. Hunter not only played the lead but co-produced as well. NBC targeted the series for the 1964-65 season. Two additional announcements from Warner Brothers also guaranteed Jeff work. First, the studio said it would add 30 minutes of story to the 57-minute original pilot and release the new film overseas. Second, a new test film, this one 90 minutes long, in color, and doubling as a second pilot and TV movie, would be shot and partly financed by NBC. Between the Ford Western and the Temple Houston Westerns for Warners and NBC, Jeff Hunter had plenty of work ahead. Then, suddenly, everything changed. Warner Brothers tracked Hunter down in Acapulco and asked him to return to California because Temple Houston was going into production immediately, and the season premiere was less than two months away. -

The Escape! Radio Program Dee-Scription: Home >> D D Too Home >> Radio Logs >> Escape!

The Escape! Radio Program Dee-Scription: Home >> D D Too Home >> Radio Logs >> Escape! Background Dramas of escape, romance and adventure comprised a great deal of the drama anthologies during the Golden Age of Radio. One might well make the argument that adventure dramas broadcast over one canon or another throughout the era were among the top five most popular genres of the era. They also found their way into any number of adventure productions, a sampling of which follow: 1930 World Adventures 1931 Strange Adventure 1932 Bring'em Back Alive 1932 Captain Diamond’s Adventures 1932 Captain Jack 1932 The Elgin Adventurer's Club 1932 World Adventurer's Club 1933 The Stamp Adventurer’s Club 1935 The Desert Kid 1935 Magic Island 1937 The Cruise of The Poll Parrot 1937 True Adventures 1937 Your Adventurers 1939 Imperial Intrigue 1939 The Order of Adventurers 1940 Thrills and Romance 1941 Adventure Stories 1942 Road to Danger 1942 The Whistler 1943 Escape From . 1943 Foreign Assignment 1943 Romance 1944 Adventure Ahead 1944 Dangerously Yours 1944 Stories of Escape 1944 The Man Called 'X' 1944 Vicks Matinee Theater 1945 Adventure 1946 Tales of Adventure 1947 Adventure Parade 1947 Escape! 1947 High Adventure 1947 The Adventurer's Club 1948 This Is Adventure 1949 Dangerous Assignment 1950 Stand By for Adventure 1952 Escape with Me 1953 The Adventurer 1974 CBS Radio Mystery Theater 1977 General Mills Radio Adventure Theater 1977 CBS Radio Adventure Theater Announcement of Escape to air in the summer of 1947 During an era when the word 'romance' still implied adventure as well as emotional and physical passion, the words 'romance' and 'adventure' were often viewed as synonymous with each other in the titles of hundreds of Radio canons of both the earliest and latest Golden Age Radio broadcasts. -

The Voyage of the Scarlet Queen , He and Aurandt Worked Together on the Green Stories of Men Who Made Them Monuments

voyage.qxd:8 pg. Booklet 6/1/10 10:05 PM Page 1 CD 6 The Courtship of Anna May Lamour - 9/18/1947 THE VOYAGE OF Shore Leave and the Unhappy Wife - 9/25/1947 THE SCARLET QUEEN CD 7 The Fat Trader and the Sword of Apokaezhan - Program Guide by Jack French 10/2/1947 The Tattooed Beaver and Baby Food for Pare Pare - The rare combination of talent that went into producing The Voyage 10/9/1947 of the Scarlet Queen can best be described as “the perfect storm.” It brought together two excellent lead actors, a superb duo of radio’s best writers, a highly CD 8 skilled trio of sound effects artists, and a respected musician to compose a lavish Ah Sin and the Balinese Beaux Arts Ball - Scarlet Queen regular Barton Yarborough and distinctive score to blend it together. The result was certainly the best radio 10/16/1947 series that ever aired on the Mutual Network. Grafter’s Fort and the Black Pearl of Galahla Bay - 10/23/1947 Elliott Lewis (1917-1990) deserves all the credit for putting this remarkable series together in 1947, just two years after World War II ended. CD 9 This series, telling the fascinating and exotic story of a sailing vessel in its quest King Ascot And The Maid In Waiting - 10/30/1947 for a Chinese treasure, would take listeners on dozens of remarkable adventures Lonely Sultan of Isabella De Basilan - 11/6/1947 in ports of call throughout the Pacific Ocean and the China Sea. -

Intraparty in the US Congress.Pages

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd17764 Author Bloch Rubin, Ruth Frances Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. -

Narrative Analysis and Framing of Governor Brownback's

Narrative analysis and framing of Governor Brownback’s state funding crisis in 2015: a case study of press secretary Eileen Hawley by Molly Jaqueline Hadfield B.A., University of Kansas 2012. A THESIS submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Journalism and Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Approved by: Major Professor Steven Smethers Copyright © Molly Hadfield 2019. Abstract Sam Brownback’s tumultuous tenure as Governor of Kansas required talented public relations people to work with the media and help him sell his budget ideas to the state. His second of three Communications Directors, Eileen Hawley, served at the time of Brownback’s 2015 tax cuts that caused a massive budget shortfall, plunging the state into a financial crisis. This case study examines the effectiveness of framing strategies used by Hawley, who employed a more politically neutral stance during her messaging surrounding the Kansas budget shortfall. This study uses in-depth interviews with Hawley and Statehouse reporters to assess Hawley’s strategies in handling the ensuing financial crisis. Previous studies have shown that communications directors who present material in a more neutral manner gain the trust of the media, and therefore their frames have more saliency in the press. This study reveals mixed results in using such a strategy, with generally negative assessments from Capital reporters. Table of Contents Chapter 1- Introduction………………………………………………………………………..…1