View, Read, and Download the Full Thesis Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![FACT SHEET [Barangay Tangos, Navotas City]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8176/fact-sheet-barangay-tangos-navotas-city-128176.webp)

FACT SHEET [Barangay Tangos, Navotas City]

FACT SHEET [Barangay Tangos, Navotas City] QUICK FIGURES* Total population: 35,427 No. of families: 7,560 Total land area: 33.31 Ha. *Based on the Barangay profile Contact persons: Tangos North – Brgy. Secretary Olive Cagalingan, (+63 927 400 9542) Tangos South – Brgy. Capt. Wilfredo Mariano (+632 351 5290) FIGURE 1. Division of Tangos North and Tangos South 1. Location and general description oF community • Tangos is an urban coastal community located in the northern portion of Navotas City • On 25 July 2018, Tangos is divided into two barangays: Tangos North and Tangos South (See Figure 1). • It is bordered by San Roque to the South, Tangos River and Barangay Tanza to the East, and Manila Bay to the West and North (See Figure 2) • About 80% of the residents live at the riverside and seaside, on land that they do not own. The remaining 20 % are tenants or have their own houses. • As an urban coastal community, the primary livelihoods are related to the fishing industry. FIGURE 2. Map showing location and boundaries of Barangay Tangos, Navotas 2. Economic activities • Livelihood: o Fishing, driving public utility vehicles, and laborers (80%) o Small-scale business owners or those described as belonging to higher income brackets (20%) o Local fishing activities are further subdivided depending on ownership of livelihood assets (boat owners, fish laborers, shellfish gatherers, shrimp paste makers). Page 1 of 2 • The Barangay acknowledges that pollution and environmental degradation have negatively impacted the livelihood of many residents. The Barangay profile notes that the drop-in fish catch has decreased the earnings of residents and has forced some businesses to close down. -

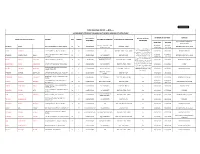

Page 1 AMOUNT of MEDICAL SERVICES LABORATORIES, DATE CONTROL MEDICINES TOTAL NAME of PATIENTS ADDRESS DENTAL & GRANTED NO

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health JOSE R. REYES MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER LIST OF PATIENTS MEDICAL ASSISTANCE TO INDIGENT PATIENTS FOR THE PERIOD FEBUARY 1 TO 29, 2020 AMOUNT OF MEDICAL SERVICES LABORATORIES, DATE CONTROL MEDICINES TOTAL NAME OF PATIENTS ADDRESS DENTAL & GRANTED NO. AND MED HOSPITAL FEES ASSISTANCE DIAGNOSTICS SUPPLIES PROCEDURES 10-Oct-19 20-01 MALINAO, EDWIN M. 106 PH2 LETRE ROAD ST. BRGY TONSUYA MALABON - CITY 3,870.00 - 3,870.00 8-Nov-19 20-02 SERRANO, ANGELIE ROSE B. 782 J. PLANAS ST. BRGY 163 TONDO MANILA - 585.00 - 585.00 11-Nov-19 20-03 BAWISAN, LUCITA B. 809 I MERCADO ST. BRGY 50 TONDO MANILA - 570.00 - 570.00 13-Nov-19 20-04 LEGARTO, IMELDA 1254 C SAN ANDRES ST MALATE MANILA 312.00 - - 312.00 21-Nov-19 20-05 ROQUE, CRISTINA B. BLK 6 L33 PH3D TAWILIS ST. BRGY 28 DAGAT-DAGATAN - CALOOCAN CITY 157.50 - 157.50 25-Nov-19 20-06 ROQUE, MA. TERESA D. 8 AGNO ST. BRGY DOÑA JOSEFA QUEZON CITY 1,134.00 360.00 - 1,494.00 26-Nov-19 20-07 MANARANG, ROSALYN M. 2418 SULU ST. BRGY 364 STA. CRUZ MANILA - 210.00 - 210.00 27-Nov-19 20-08 BASAL, ALFREDO V. BLK20 LOT19 PH1B ALUMAHAN ST. BRGY KAUNLARAN - NAVOTAS CITY 1,590.00 - 1,590.00 28-Nov-19 20-09 ESCORIAL, ESTER M. 143 CRESPO ST. BRGY GUILID LIGAO ALBAY - 3,560.00 - 3,560.00 28-Nov-19 20-10 RIVERA, LEONARD S. BRGY 331 STA. CRUZ MANILA 624.00 360.00 - 984.00 29-Nov-19 20-11 OREO, EUGENIA P. -

FY 2021 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act

FY 2021 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act UACS / Sub Program Project Component Description Type of Work Target Physical Target Amount Operating Unit / Project Component ID Unit (PHP) Implementing Office National Capital Region 2,045 projects 51,299,970,000 Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office 138 projects 4,300,308,000 OO1: Ensure Safe and Reliable National Road System 19 projects 738,933,000 Asset Preservation - Preventive Maintenance - Primary Roads 5,789,000 1. P00400888LZ 310101100282000 MYOA 1,478,000 Daang Maharlika (LZ) - K0026 + (-446.80) - K0026 +(-120) P00400888LZ-CW1 Preventive Maintenance of Road: Preventive Lane Km 1.308 1,448,440 Las Asphalt Overlay - along Daang Maintenance of Piñas-Muntinlupa Maharlika (LZ) (S03285LZ) K0026 + Road: Asphalt District (-446.80) - K0026 + (-120) Overlay Engineering Office / Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office P00400888LZ-EAO 29,560 Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office / Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office 2. P00505481LZ 310101100412000 4,311,000 Paranaque-Sucat Rd - Chainage 0 - Chainage 158 P00505481LZ-CW1 Preventive Maintenance of Road: Preventive Lane Km 0.632 4,224,780 Las Asphalt Overlay - at Specific Maintenance of Piñas-Muntinlupa Locations along Paranaque-Sucat Road: Asphalt District Rd (S03293LZ) 0 - 158 Overlay Engineering Office / Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office P00505481LZ-EAO 86,220 Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office / Las Piñas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office -

2019 Iiee Metro Manila Region Return to Sender

2019 IIEE METRO MANILA REGION RETURN TO SENDER STATUS firstName midName lastname EDITED ADDRESS chapterName RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ANSELMO FETALVERO ROSARIO Zone 2 Boulevard St. Brgy. May-Iba Teresa Metro East Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JULIUS CESAR AGUINALDO ABANCIO 133 MC GUINTO ST. MALASAGA, PINAGBUHATAN PASIG . Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ALVIN JOHN CLEMENTE ABANO NARRA STA. ELENA IRIGA Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS Gerald Albelda Abantao NO.19 . BRGY. KRUS NA LIGAS. DILIMAN QUEZON CITY Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER JEAN MIGHTY DECIERDO ABAO HOLCIM PHILIPPINES INC. MATICTIC NORZAGARAY BULACAN Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS MICHAEL HUGO ABARCA avida towers centera edsa cor. reliance st. mandaluyong city Metro West Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Jeffrey Cabagoa ABAWAG 59 Gumamela Sta. Cruz Antipolo Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER Angelbert Marvin Dolinso ABELLA Road 12 Nagtinig San Juan Taytay Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS AHERN SATENTES ABELLA NAGA-NAGA BRGY. 71 TACLOBAN Metro South Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JOSUE DANTE ABELLA JR. 12 CHIVES DRIVE ROBINSONS HOMES EAST SAN JOSE ANTIPOLO CITY Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS ANDREW JULARBAL ABENOJA 601 ACACIA ESTATE TAGUIG CITY METRO MANILA Metro West Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS LEONARDO MARQUEZ ABESAMIS, JR. POBLACION PENARANDA Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ELONA VALDEZ ABETCHUELA 558 M. de Jesus St. San Roque Pasay City Metro South Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Franklin Mapa Abila LOT 3B ATIS ST ADMIRAL VILLAGE TALON TRES LAS PINAS CITY METRO MANILA Metro South Chapter RTS MOVED OUT Marie Sharon Segovia Abilay blk 10 lot 37 Alicante St. -

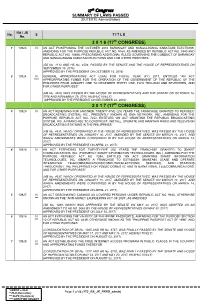

17Th Congress SUMMARY of LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration)

17th Congress SUMMARY OF LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration) RA / JR No. S T I T L E No. 2 0 1 6 (17th CONGRESS) 1 10923 N AN ACT POSTPONING THE OCTOBER 2016 BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9164, AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9340 AND REPUBLIC ACT NO. 10656, PRESCRIBING ADDITIONAL RULES GOVERNING THE CONDUCT OF BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES (SB No. 1112 AND HB No. 3504, PASSED BY THE SENATE AND THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON SEPTEMBER 13, 2016) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON OCTOBER 15, 2016) 2 10924 N GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT (GAA) FOR FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017, ENTITLED “AN ACT **** APPRORPRIATING FUNDS FOR THE OPERATION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPINES FROM JANUARY ONE TO DECEMBER THIRTY ONE, TWO THOUAND AND SEVENTEEN, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES” (HB No. 3408, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE SENATE ON OCTOBER 19, 2016 AND NOVEMBER 28, 2016, RESPECTIVELY) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON DECEMBER 22, 2016) 2 0 1 7 (17th CONGRESS) 3 10925 N AN ACT RENEWING FOR ANOTHER TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC., PRESENTLY KNOWN AS GMA NETWORK, INC., AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7252, ENTITLED “AN ACT GRANTING THE REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. A FRANCHISE TO CONSTRUCT, INSTALL, OPERATE AND MAINTAIN RADIO AND TELEVISION BROADCASTING STATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES” (HB No. 4631, WHICH ORIGINATED IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON JANUARY 16, 2017, AMENDED BY THE SENATE ON MARCH 13, 2017, AND WHICH AMENDMENTS WERE CONCURRED IN BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON MARCH 14, 2017) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON APRIL 21, 2017) 4 10926 N AN ACT EXTENDING FOR TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO SMART COMMUNICATIONS, INC. -

17 APRIL 2021, Saturday Headline STRATEGIC April 17, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article

17 APRIL 2021, Saturday Headline STRATEGIC April 17, 2021 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article PH vows to cut gas emissions by 75 percent By: Krissy Aguilar - Reporter / @KAguilarINQ INQUIRER.net / 04:36 PM April 16, 2021 Screengrab from RTVM’s Facebook page MANILA, Philippines — The Philippines has committed to the United Nations its target to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 75 percent between 2020 and 2030. The Philippines submitted its first Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) on April 15, as seen on the latter’s website. “The Philippines commits to a projected GHG emissions reduction and avoidance of 75%, of which 2.71% is unconditional and 72.29% is conditional, representing the country’s ambition for GHG mitigation for the period 2020 to 2030 for the sectors of agriculture, wastes, industry, transport, and energy,” the country’s NDC stated. The unconditional target of 2.71 percent means the government is undertaking this “using nationally mobilized resources” while the remaining 72.29 percent conditional target relies on support from the international community. “The Philippines shall undertake adaptation measures across but not limited to, the sectors of agriculture, forestry, coastal and marine ecosystems, and biodiversity, health, and human security, to preempt, reduce and address residual loss and damage,” the NDC read. The UNFCCC said 192 of 16 parties to the Paris Agreement have submitted their first -

Republic of the Philippines

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT ENGINEER Malabon Navotas District Engineering Office C4 Road, Bagumbayan North, Navotas City February 21, 2019 BID BULLETIN NO. 06-2019 SUBJECT: Push Through with the Submission/Opening of Bids Notice is hereby announced to all Participating Bidders that the listed projects below will push through with the Submission/Opening of Bids, to wit, From: Schedule of Bidding as Contract ID Description Advertise No. Rehabilitation of Road, Francisco St., 19OA0028 Brgy. San Rafael Village, Navotas City January 30, 2018 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 150 CD Rehabilitation of Road, Bagong Kalsada, 19OA0029 Brgy. Tangos South, Navotas City January 30, 2018 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 150 CD Rehabilitation of Road, Tuazon St. Brgy. 19OA0030 Potrero, Malabon City February 06, 2019 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 150 CD Rehabilitation of Road, Paezville, Brgy. 19OA0031 Dampalit, Malabon City February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 90 CD Rehabilitation of Road, B. Rivera St. 19OA0032 Brgy. Tinajeros, Malabon City February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 150 CD Construction of Riverwall along South 19OA0033 Pinagkabalian River, Brgy. Muzon, February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) Malabon City Contract Duration: 150 CD Construction of Road including Drainage 19OA0034 Canal within Tanza Socialized Housing February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) (Interior I), Navotas City Contract Duration: 90 CD Construction of Riverwall along Malabon- 19OA0035 Tullahan River (Phase II) Brgy. NBBS February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) Dagat-Dagatan, Navotas City Contract Duration: 156 CD Construction of Tanza Road Dike 19OA0036 (Phase I) Brgy. Tanza 2, Navotas City February 6, 2019 (10:00AM) Contract Duration: 161 CD Construction of Tanza Road Dike 19OA0037 (Phase II) Brgy. -

Dole Regional Office __Ncr___ Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form

DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE __NCR___ GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS EDUCATIONAL NATURE OF WORK/ NAME (Last Name, First Name, MI) ADDRESS AGE GENDER DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED OFFICE/PLACE OF ASSIGNMENT ATTAINMENT ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract completed or START DATE END DATE preterminated Profiling of the child-laborer/s in Barangay Certificate, T.O.R, 1X1 & 18/01/2018 - 3/08/2018 - ADRIMISIN JOMAR 303-C MATIMTIMAN ST. TONDO, MANILA 23 M COLLEGE LEVEL DOLE NCR - OARD the barangay; Encoding of EXTENDED UNTIL DEC. 31, 2018 2X2 PICTURE 04/08/2018 31/12/2018 registrants in the Skills Registry ALFAR EDUARDO 2254 F. MUÑOZ ST., MALATE, MANILA 26 M COLLEGE GRAD T.O.R DOLE NCR - IMSD - ACCOUNTING -do- 03/19/2018 09/24/2018 RESIGNED 7/9/2018 3 BLOCK 30 AMPALAYA ST., BRGY.,TUMANA, 22/01/2018 - 01/08/2018 - ATACADOR KIMBERLY GRACE BULAS 25 F COLLEGE GRAD NO DOCUMENTS DOLE NCR - IMSD -do- EXTENDED UNTIL DEC. 31, 2018 MARIKINA CITY 02/08/2018 31/12/2018 COPY OF GRADES, BRGY INDIGENCY, BACANI ANGELO ARCILLANO 2364 A. LEVERIZA ST., PASAY CITY 29 M COLLEGE LEVEL DOLE NCR - IMSD - CASHIER -do- 01/10/2018 07/24/2018 PROMOTED TO PBE-SRS 1X1 & 2X2 PICTURE BOLANDRINA MELVIN VALLADORES 1445 7TH ST., FABIE SUBD. PACO MANILA M COLLEGE LEVEL NO DOCUMENTS DOLE NCR - TSSD - EPWW -do- 03/01/2018 09/12/2018 ENDO 106 B CONSTELLATION ST., DON CARLOS BOLAÑO LORY MAE BANAGDAS 21 F COLLEGE GRAD Brgy. Certification DOLE NCR - TSSD LRLS -do- 03/16/2018 09/26/2018 RESIGNED 6/20/2018 VILLAGE, PASAY CITY CARDENAS DONABEL ESCAMILLAS UNIT 208 MONTE CARLO BLDG. -

Policy Statements 4 2017.Indd

POLICY STATEMENTS* July-August 2017 President Rodrigo Roa Duterte Republic of the Philippines * Policy Statements and Issuances are culled online from the speeches and issuances of the President posted at http://www.gov.ph/offi cial-gazette/ and www.rtvm.gov.ph EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION BOARD Editor-in-Chief: Usec. George A. Apacible Editorial Consultant: Benjamin R. Felipe Production Coordination Eileen Cruz-David Data Gathering Monica N. Ladisla Editing and Proofreading John S. Salvadora Regin Raymund D. Dais Graphic and Lay-out Design Raymond R. dela Rama Jhon Enrel S. Tan Table of Contents Security, Peace & Justice: 1 Remain Steadfast and United Against Drugs and Terrorism While Trying Our Best to Improve the Economy Security, Peace & Justice: 15 Build on Past Gains to Further Strengthen the Philippine Air Force Good Governance & Anti-Corruption: 18 Do What is Fair Play and What is Only Legal and Right Good Governance & Anti-Corruption: 35 A Bangsamoro Basic Law that is Consistent with the Constitution and Aspiration of the Moro People Mabuting Pamamahala at Anti-Kurapsyon: 37 Pagkalinga sa mga Naulila ng Magigiting na Sundalo at Pulis Good Governance & Anti-Corruption: 50 Government Workers Must Work for the People and Honestly Earn Their Keep for the Day Photo Gallery 53 Security, Peace and Justice: 80 A Better and More Equipped Police Force to Fight the Enemies of the State Security, Peace and Justice: 91 Emulate the Patriotism of Our Heroes to Prevail Against Criminality, Terrorism and Drugs PRESIDENTIAL ISSUANCES 96 Executive Orders 96 Administrative Orders 97 Memorandum Circulars 97 Memorandum Order 98 Proclamations 99 REPUBLIC ACTS 106 JULY-AUGUST Security, Peace & Justice: Remain Steadfast and United Against Drugs and Terrorism While Trying Our Best to Improve the Economy (50th Founding Anniversary of Davao del Norte, Tagum City, July 1, 2017) ng akong mata limitado. -

Department of Budget and Management Boncodin Hall, General Solano Street

o F Fl C LA L E REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF BUDGET AND MANAGEMENT BONCODIN HALL, GENERAL SOLANO STREET. SAN MIGUEL. MANILA LOCAL BUDGET MEMORANDUM NO. 77-B Date: December 21, 2018 To : LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES, MEMBERS OF THE LOCAL SANGGUNIAN, LOCAL BUDGET OFFICERS, LOCAL TREASURERS, LOCAL PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT COORDINATORS, LOCAL ACCOUNTANTS, AND ALL OTHERS CONCERNED Subject : ADJUSTED FY 2019 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT (IRA) SHARES OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS (LGUs) 1.0 Section 89 of the General Provisions (GPs) of the FY 2018 General Appropriations Act (GAA), Republic Act (RA) No. 10964 provides, in part, that all valid adjustments, changes, modifications, or alterations in any of the factors affecting the computation of IRA that occurred or happened, including final and executory court decisions made effective, during the current fiscal year, shall only be considered and implemented by the DBM in the subsequent fiscal year from receipt by the DBM of the notice of said change. 2.0 Corollary thereto, the IRA shares of LGUs, which are automatically appropriated, shall be apportioned among LGUs, including provinces, cities, and municipalities created, approved, and ratified in 2018 in accordance with the allocation formula prescribed under Section 285 of the Local Government Code of 1991 (RA No. 7160). 3.0 Consistent with the foregoing, and by virtue of the enactment of the various laws, the barangays listed hereunder shall be included in the allocation of the FY 2019 IRA shares of LGUs: Charter Barangay RA No. 10933 Barangay North Bay Boulevard South (NBBS) Proper, Navotas City RA No. 10933 Barangay NBBS Kaunlaran, Navotas City RA No. -

REGIONAL REPORT on the APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-National Capital Region

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-National Capital Region May 2019 No. Company Name and Address Project Name Date Approved Proposed Renovation of One (1) Room at Ground Floor and Cecilia G. Peňa 1 Exterior Repainting of Two (2) Storey Building 1643 Pedro Gil 5/2/2019 1639 Pedro Gil St., Paco, Manila St., Paco, Manila St. Jude College - Phinma Proposed Repair of Structural Columns and Beams 2 5/6/2019 Don Quijote St., Dapitan, Sampaloc, Manila St. Jude Colleges, Don Quijote St., Dapitan, Sampaloc, Manila Proposed Coffee Shop Interior Renovation Luona Wang / JVRS Food Services 3 Ground Floor, The Pearl Hotel Manila, Gen. Luna St., Ermita, 5/6/2019 32A Wharton Parksuites, Masangkay, Sta. Cruz, Manila Manila Susan B. Lim Proposed Renovation of Two (2) Storey Building 4 5/7/2019 555 Mag. Mapa St., Bacood, Sta. Mesa, Manila 555 Mag. Mapa St., Bacood, Sta. Mesa, Manila VFC Land Resources Inc. / Maricel B. Joyag Proposed Demolition of One (1) Storey Old Warehouse 5 5/7/2019 Marquez De Camillas St., Brgy. 664 Zone 71, Paco, Manila Marquez De Camillas St., Brgy. 664 Zone 71, Paco, Manila Jeffrey L. Aldovino Proposed Construction of One (1) Storey Residential Building 6 5/9/2019 Nicodemus St., Capitol Homesite, Cotta, Lucena City Blk 2 Lot 14, Loyola St., Brgy. 397, Sampaloc, Manila Proposed Renovation of 7-Eleven Store Ulysses V. Borral / Phil. Seven Corporation 7 E. Bldg. Chinese General Hospital, 286 Blumentritt Road, 5/22/2019 286 Blumentritt Road, Sampaloc, Manila Sampaloc, Manila Marilyn M. Cabreros Proposed Renovation / Partition and Repair Works 5/27/2019 8 847 Norma St., Sampaloc, Manila 847 Norma St., Sampaloc, Manila Josefina V. -

Dole Regional Office __Ncr___ Government Internship Program (Gip) Beneficiaries Monitoring Form

DOLE-GIP_Form C DOLE REGIONAL OFFICE __NCR___ GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM (GIP) BENEFICIARIES MONITORING FORM DURATION OF CONTRACT REMARKS EDUCATIONAL NATURE OF WORK/ NAME (Last Name, First Name, MI) ADDRESS AGE GENDER DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED OFFICE/PLACE OF ASSIGNMENT ATTAINMENT ASSIGNMENT (e.g. Contract completed or START DATE END DATE preterminated Barangay Certificate, T.O.R, 18/01/2018 - 3/08/2018 - ADRIMISIN JOMAR 303-C MATIMTIMAN ST. TONDO, MANILA 23 M COLLEGE LEVEL DOLE NCR - OARD EXTENDED UNTIL DEC. 31, 2018 1X1 & 2X2 PICTURE 04/08/2018 31/12/2018 Profiling of the child-laborer/s in ALFAR EDUARDO 2254 F. MUÑOZ ST., MALATE, MANILA 26 M COLLEGE GRAD T.O.R DOLE NCR - IMSD - ACCOUNTING the barangay; Encoding of 03/19/2018 09/24/2018 RESIGNED 7/9/2018 registrants in the Skills Registry 3 BLOCK 30 AMPALAYA ST., BRGY.,TUMANA, System; Assisting medical, 22/01/2018 - 01/08/2018 - ATACADOR KIMBERLY GRACE BULAS 25 F COLLEGE GRAD NO DOCUMENTS DOLE NCR - IMSD educational and other social EXTENDED UNTIL DEC. 31, 2018 MARIKINA CITY 02/08/2018 31/12/2018 services provided by the various COPY OF GRADES, BRGY agencies such as DSWD and BACANI ANGELO ARCILLANO 2364 A. LEVERIZA ST., PASAY CITY 29 M COLLEGE LEVEL DOLE NCR - IMSD - CASHIER 01/10/2018 07/24/2018 PROMOTED TO PBE-SRS INDIGENCY, 1X1 & 2X2 DOH; Assisting in the conduct PICTURE of the monitoring of DOLE BOLANDRINA MELVIN VALLADORES 1445 7TH ST., FABIE SUBD. PACO MANILA M COLLEGE LEVEL NO DOCUMENTS DOLE NCR - TSSD - EPWW Programs implemented by Field 03/01/2018 09/12/2018 ENDO Office as the need arises; and Performing other clerical and 106 B CONSTELLATION ST., DON CARLOS BOLAÑO LORY MAE BANAGDAS 21 F COLLEGE GRAD Brgy.