Seasonal Migration and Settlement Around Lake Chad: Strategies for Control of Resources in an Increasingly Drying Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sitwa Report on Infrastructure Development

SITWA PROJECT: STRENGTHENING THE INSTITUTIONS FOR TRANSBOUNDARY WATER MANAGEMENT IN AFRICA CONSULTANCY SERVICES TO ASSESS THE NEEDS AND PREPARE AN ACTION PLAN FOR SITWA/ANBO SUPPORT SERVICES IN INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT IN THE AFRICAN RIVER BASIN ORGANIZATIONS SITWA REPORT ON INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union RAPPORT SITWA SUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DES INFRASTRUCTURES DANS LES OBF AFRICAINS 3 Table des matiÈRES Table des matières ...................................................................................... 3 AbrEviations ............................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................... 7 Executive summary .................................................................................... 8 List of tables .............................................................................................. 9 List of figures ............................................................................................ 9 1. Background and objectives of the consultancy ........................................ 10 1.1 ANBO’s historical background and objectives ............................................................................. 10 1.2 Background and objectives of SITWA ......................................................................................... -

B133 Cameroon's Far North Reconstruction Amid Ongoing Conflict

Cameroon’s Far North: Reconstruction amid Ongoing Conflict &ULVLV*URXS$IULFD%ULHILQJ1 1DLUREL%UXVVHOV2FWREHU7UDQVODWHGIURP)UHQFK I. Overview Cameroon has been officially at war with Boko Haram since May 2014. Despite a gradual lowering in the conflict’s intensity, which peaked in 2014-2015, the contin- uing violence, combined with the sharp rise in the number of suicide attacks between May and August 2017, are reminders that the jihadist movement is by no means a spent force. Since May 2014, 2,000 civilians and soldiers have been killed, in addition to the more than 1,000 people kidnapped in the Far North region. Between 1,500 and 2,100 members of Boko Haram have reportedly been killed following clashes with the Cameroonian defence forces and vigilante groups. The fight against Boko Haram has exacerbated the already-delicate economic situation for the four million inhabitants of this regionௗ–ௗthe poorest part of the country even before the outbreak of the conflict. Nevertheless, the local population’s adaptability and resilience give the Cameroonian government and the country’s international partners the opportunity to implement development policies that take account of the diversity and fluidity of the traditional economies of this border region between Nigeria and Chad. The Far North of Cameroon is a veritable crossroads of trading routes and cultures. Besides commerce, the local economy is based on agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, tourism, transportation of goods, handcrafts and hunting. The informal sector is strong, and contraband rife. Wealthy merchants and traditional chiefsௗ–ௗoften members of the ruling party and high-ranking civil servantsௗ–ௗare significant economic actors. -

Region: West Africa (14 Countries) (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte D’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo)

Region: West Africa (14 Countries) (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo) Project title: Emergency assistance for early detection and prevention of avian influenza in Western Africa Project number: TCP/RAF/3016 (E) Starting date: November 2005 Completion date: April 2007 Government counterpart Ministries of Agriculture responsible for project execution: FAO contribution: US$ 400 000 Signed: ..................................... Signed: ........................................ (on behalf of Government) Jacques Diouf Director-General (on behalf of FAO) Date of signature: ..................... Date of signature: ........................ I. BACKGROUND AND JUSTIFICATION In line with the FAO/World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Global Strategy for the Progressive Control of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), this project has been developed to provide support to the regional grouping of West African countries to strengthen emergency preparedness against the eventuality of HPAI being introduced into this currently free area. There is growing evidence that the avian influenza, which has been responsible for serious disease outbreaks in poultry and humans in several Asian countries since 2003, is spread through a number of sources, including poor biosecurity at poultry farms, movement of poultry and poultry products and live market trade, illegal and legal trade in wild birds. Although unproven, it is also suspected that the virus could possibly be carried over long distances along the migratory bird flyways to regions previously unaffected (Table 1) is a cause of serious concern for the region. Avian influenza subtype H5N1 could be transported along these routes to densely populated areas in the South Asian Subcontinent and to the Middle East, Africa and Europe. -

The Boko Haram Conflict in Cameroon Why Is Peace So Elusive? Pr

Secur nd ity a S e e c r i a e e s P FES Pr. Ntuda Ebode Joseph Vincent Pr. Mark Bolak Funteh Dr. Mbarkoutou Mahamat Henri Mr. Nkalwo Ngoula Joseph Léa THE BOKO HARAM CONFLICT IN CAMEROON Why is peace so elusive? Pr. Ntuda Ebode Joseph Vincent Pr. Mark Bolak Funteh Dr. Mbarkoutou Mahamat Henri Mr. Nkalwo Ngoula Joseph Léa THE BOKO HARAM CONFLICT IN CAMEROON Why is peace so elusive? Translated from the French by Diom Richard Ngong [email protected] © Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Yaoundé (Cameroun), 2017. Tél. 00 237 222 21 29 96 / 00 237 222 21 52 92 B.P. 11 939 Yaoundé / Fax: 00 237 222 21 52 74 E-mail : [email protected] Site : www.fes-kamerun.org Réalisation éditoriale : PUA : www.aes-pua.com ISBN: 978-9956-532-05-3 Any commercial use of publications, brochures or other printed materials of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung is strictly forbidden unless otherwise authorized in writing by the publisher This publication is not for sale All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photo print, microfilm, translation or other means without written permission from the publisher TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ………………………………………………….....……………....................…………..................... 5 Abbreviations and acronyms ………………………………………...........…………………………….................... 6 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………....................………………....….................... 7 Chapter I – Background and context of the emergence of Boko Haram in Cameroon ……………………………………………………………………………………....................………….................... 8 A. Historical background to the crisis in the Far North region ……………..……….................... 8 B. Genesis of the Boko Haram conflict ………………………………………………..................................... 10 Chapter II - Actors, challenges and prospects of a complex conflict ……………....... 12 A. Actors and the challenges of the Boko Haram conflict …………………………….....................12 1. -

Large Hydro-Electricity and Hydro-Agricultural Schemes in Africa

FAO AQUASTAT Dams Africa – 070524 DAMS AND AGRICULTURE IN AFRICA Prepared by the AQUASTAT Programme May 2007 Water Development and Management Unit (NRLW) Land and Water Division (NRL) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Dams According to ICOLD (International Commission on Large Dams), a large dam is a dam with the height of 15 m or more from the foundation. If dams are 5-15 metres high and have a reservoir volume of more than three million m3, they are also classified as large dams. Using this definition, there are more than 45 000 large dams around the world, almost half of them in China. Most of them were built in the 20th century to meet the constantly growing demand for water and electricity. Hydropower supplies 2.2% of the world’s energy and 19% of the world’s electricity needs and in 24 countries, including Brazil, Zambia and Norway, hydropower covers more than 90% of national electricity supply. Half of the world’s large dams were built exclusively or primarily for irrigation, and an estimated 30-40% of the 277 million hectares of irrigated lands worldwide rely on dams. As such, dams are estimated to contribute to 12-16% of world food production. Regional inventories include almost 1 300 large and medium-size dams in Africa, 40% of which are located in South Africa (517) (Figure 1). Most of these were constructed during the past 30 years, coinciding with rising demands for water from growing populations. Information on dam height is only available for about 600 dams and of these 550 dams have a height of more than 15 m. -

![Bibliography [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7993/bibliography-pdf-487993.webp)

Bibliography [PDF]

Ancient TL Vol. 30 No.1 2012 31 Bibliography Compiled by Daniel Richter _____________________________________________________________________________________________ From 1st November 2011 to 31st May 2012 Abafoni, J. D., Mallam, S. P., and Akpa, T. C. (2012). Comparison of OSL and ITL measurements on quartz grains extracted from sediments of the Chad Basin, N.E. Nigeria. Research Journal of Applied Sciences 6, 483-486. Altay Atlıhan, M., Şahiner, E., and Soykal Alanyalı, F. (2012). Dose estimation and dating of pottery from Turkey. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 81, 594-598. Amos, C. B., Lapwood, J. J., Nobes, D. C., Burbank, D. W., Rieser, U., and Wade, A. (2011). Palaeoseismic constraints on Holocene surface ruptures along the Ostler Fault, southern New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 54, 367-378. Andreucci, S., Bateman, M. D., Zucca, C., Kapur, S., Aksit, İ., Dunajko, A., and Pascucci, V. (2012). Evidence of Saharan dust in upper Pleistocene reworked palaeosols of North-west Sardinia, Italy: palaeoenvironmental implications. Sedimentology 59, 917-938. Anjar, J., Adrielsson, L., Bennike, O., Björck, S., Filipsson, H. L., Groeneveld, J., Knudsen, K. L., Larsen, N. K., and Möller, P. (2012). Palaeoenvironments in the southern Baltic Sea Basin during Marine Isotope Stage 3: a multi- proxy reconstruction. Quaternary Science Reviews 34, 81-92. Athanassas, C., Bassiakos, Y., Wagner, G. A., and Timpson, M. E. (2012). Exploring paleogeographic conditions at two paleolithic sites in Navarino, southwest Greece, dated by optically stimulated luminescence. Geoarchaeology 27, 237-258. Atkinson, O. A. C., Thomas, D. S. G., Goudie, A. S., and Parker, A. G. (2012). Holocene development of multiple dune generations in the northeast Rub‘ al-Khali, United Arab Emirates. -

Special Feature the Lake Chad Basin

Special feature Number 70 October 2017 Humanitarian The Lake Chad Basin: Exchange an overlooked crisis? Humanitarian Exchange Number 70 October 2017 About HPN Contents 21. Integrating civilian protection into Nigerian military policy and practice The Humanitarian Practice Network 05. Chitra Nagarajan at the Overseas Development The Lake Chad crisis: drivers, responses Institute is an independent forum and ways forward 24. where field workers, managers and Toby Lanzer policymakers in the humanitarian Sexual violence and the Boko Haram sector share information, analysis and 07. crisis in north-east Nigeria experience. The views and opinions Joe Read expressed in HPN’s publications do The evolution and impact of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin not necessarily state or reflect those of 27. Virginia Comolli the Humanitarian Policy Group or the Mental health and psychosocial needs Overseas Development Institute. and response in conflict-affected areas 10. of north-east Nigeria A collective shame: the response to the Luana Giardinelli humanitarian crisis in north-eastern Nigeria 30. Patricia McIlreavy and Julien Schopp The challenges of emergency response in Cameroon’s Far North: humanitarian 13. response in a mixed IDP/refugee setting A square peg in a round hole: the politics Sara Karimbhoy of disaster management in north- eastern Nigeria 33. Virginie Roiron Adaptive humanitarian programming in Diffa, Niger Cover photo: Zainab Tijani, 20, a Nigerian refugee 16. Matias Meier recently returned from Cameroon in the home she shares with her family in the town of Banki, Nigeria, 2017 State governance and coordination of © UNHCR the humanitarian response in north-east Nigeria Zainab Murtala and Bashir Abubakar 17. -

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries.1 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Cecilia Mann Tel.: +237 691 794 050 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.globaldtm.info/cameroon/ © IOM 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1 The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

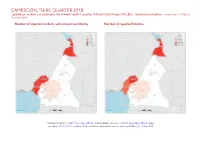

Cameroon, Third Quarter 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Updated 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 20 December 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 15 December 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 85 64 159 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 81 52 284 Development of conflict incidents from September 2016 to September Strategic developments 24 0 0 2018 2 Riots/protests 8 0 0 Methodology 3 Remote violence 4 1 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Total 203 117 447 Localization of conflict incidents 4 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from September 2016 to September 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). 2 CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Methodology Geographic map data is primarily based on GADM, complemented with other sources if necessary. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Cameroon/2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS May 2019 Highlights 2,300,000 # of children in need of humanitarian • By May 2019, UNICEF and its partners have distributed assistance 4,300,000 WASH kits to more than 78,000 people in the North-West # of people in need and South-West regions. (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019) • In May, more than 9,000 families have received Long Displacement Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLIN) through UNICEF’s 444,213 assistance in the North-West and South-West regions. # of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the North-West and South-West regions • On 20 May, the primary data collection for the education (OCHA Displacement Monitoring, December 2018) need assessment has started in the North-West and South- 237,349 West regions. # of Returnees in the North-West and South- West regions (OCHA Displacement • On 22 May, a case of polio virus type 2 from an Monitoring, December 2018) environmental sample was confirmed in Mada health 372,854 # of IDPs and Returnees in the Far-North district of Logone-et-Chari in the Far-North region. region (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix 18, April 2019) 102,963 UNICEF’s Response with Partners # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas (UNHCR Fact Sheet, May 2019) Sector Total UNICEF Total Target Results* Target Results* WASH: People provided with UNICEF Appeal 2019 374,758 29,941 75,000 20,181 access to appropriate sanitation US$ 39.3 million Education: Number of boys and girls (3 to 17 years) affected by 363,300 2,415 217,980 0 crisis receiving learning materials Nutrition**: Number of children Funds aged 6-59 months with SAM 60,255 23,459 65,064 24,413 received admitted for treatment $ 4.5M Carry- Child Protection: Children over $ 3.2 M reached with psychosocial support 563,265 90,966 289,789 39,173 2019 funding through child friendly/safe spaces requirement: C4D: Persons reached with key $39.3 M life- saving & behaviour change 385,000 35,275 messages *Total results are cumulative. -

The Hydro-Isostatic Rebound Related to Megalake Chad (Holocene, Africa): First Numerical Modelling and Significance for Paleo-Shorelines Elevation

water Article The Hydro-Isostatic Rebound Related to Megalake Chad (Holocene, Africa): First Numerical Modelling and Significance for Paleo-Shorelines Elevation Anthony Mémin 1, Jean-François Ghienne 2, Jacques Hinderer 2, Claude Roquin 2 and Mathieu Schuster 2,* 1 Université Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, IRD, Géoazur, 06560 Valbonne, France; [email protected] 2 Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg UMR 7516, 67084 Strasbourg, France; [email protected] (J.-F.G.); [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (C.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 13 November 2020 Abstract: Lake Chad, the largest freshwater lake of north-central Africa and one of the largest lakes of Africa, is the relict of a giant Quaternary lake (i.e., Megalake Chad) that developed during the early- to mid-Holocene African Humid Period. Over the drylands of the Sahara Desert and the semi-arid Sahel region, remote sensing (optical satellite imagery and digital elevation models) proved a successful approach to identify the paleo-shorelines of this giant paleo-lake. Here we present the first attempt to estimate the isostatic response of the lithosphere due to Megalake Chad and its impact on the elevation of these paleo-shorelines. For this purpose, we use the open source TABOO software (University of Urbino, Italy) and test four different Earth models, considering different parameters for the lithosphere and the upper mantle, and the spatial distribution of the water mass. We make the simplification of an instantaneous drying-up of Megalake Chad, and compute the readjustment related to this instant unload. -

Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing Current Challenges and Adapting to Future Needs

Seminar Proceedings Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing current challenges and adapting to future needs World Water Week, Stockholm, August 16-22, 2009 Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing current challenges and adapting to future needs World Water Week, Stockholm, August 16-22, 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 4 Seminar Overview 5 The Project for Water Transfer from Oubangui to Lake Chad 9 The Application of Climate Adaptation Systems and Improvement of 19 Predictability Systems in the Lake Chad Basin The Aquifer Recharge and Storage Systems to Halt the High Level of Evapotranspiration 29 Appraisal and Up-Scaling of Water Conservation and Small-Scale Agriculture Technologies 45 Summary and Conclusions 59 4 Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following persons for their support; namely: Claudia Casarotto for the technical revision and Edith Mahabir for editing. Thanks to their continuous support and prompt action, it was possible to meet the very narrow deadline to produce it. Seminar Overview 5 Seminar Overview Maher Salman, Technical Officer, NRL, FAO Alex Blériot Momha, Director of Information, LCBC The entire geographical basin of the Lake Chad covers 8 percent of the surface area of the African continent, shared between the countries of Algeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Libya, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. In recent decades, the open water surface of Lake Chad has reduced from approximately 25 000 km2 in 1963, to less than 2 000 km2 in the 1990s heavily impacting the Basin’s economic activities and food security.