BNJ (Suing by Her Lawful Father and Litigation Representative, B) V SMRT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation Into Reliability of the Jubilee Line

Investigation into Reliability: London Underground Jubilee Line An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science By Jack Arnis Agolli Marianna Bailey Errando Berwin Jayapurna Yiannis Kaparos Date: 26 April 2017 Report Submitted to: Malcolm Dobell CPC Project Services Professors Rosenstock and Hall-Phillips Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. Abstract Metro systems are often faced with reliability issues; specifically pertaining to safety, accessibility, train punctuality, and stopping accuracy. The project goal was to assess the reliability of the London Underground’s Jubilee Line and the systems implemented during the Jubilee Line extension. The team achieved this by interviewing train drivers and Transport for London employees, surveying passengers, validating the stopping accuracy of the trains, measuring dwell times, observing accessibility and passenger behavior on platforms with Platform Edge Doors, and overall train performance patterns. ii Acknowledgements We would currently like to thank everyone who helped us complete this project. Specifically we would like to thank our sponsor Malcolm Dobell for his encouragement, expert advice, and enthusiasm throughout the course of the project. We would also like to thank our contacts at CPC Project Services, Gareth Davies and Mehmet Narin, for their constant support, advice, and resources provided during the project. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Land Transport Authority, Singapore Singapore

Sample Profile LandSingapore Transport LTA Authority, Singapore Key information Current network Parameters Details System Details Ownership Fully government owned Metrorail Service area Singapore covering a population Line Length (km) Stations of 5.54 million (2015) North-South Line (Red) xxx xxx Modes Bus, MRT, LRT and taxi services operated East-West Line (Green) xxx xxx Operators of SMRT Corporation, SBS Transit Circle Line (Orange) xxx xxx bus and rail Circle Line Extension xxx xxx Modal share of public transport North-East Line (Purple) xxx xxx Downtown Line (Phase I) xxx xxx Rail, 31% Downtown Line (Phase II) xxx xxx Bus, 55% Total xxx xxx Taxi, 14% Light rail Line Length (km) Stations Bukit Panjang xxx xxx Key facts Sengkang xxx xxx • xxx% of all journeys in peak hours undertaken Punggol xxx xxx on public transport • xxx% of public transport journeys of less than Total xxx xxx 20 km completed within 60 minutes Bus • xxx in xxx households are within 10 minutes walk from a train station Total routes operated xxx Source: LTA Sample Profile Size and Growth Growth in network MRT network growth (km) 180 xxx • xxx xxx LTA’s MRT network has increased at a CAGR of xxx% during 160 xxx xxx 2010-2015. 140 xxx • However, the LRT network has remained constant at xxx km since 2005. 120 100 km Growth in ridership 80 60 40 20 4.5 xxx 5 4.4 0 xxx 4 4.3 xxx 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 4.2 3 4.1 % 4 2 Ridership trend 3.9 1 3.8 • System-wise average daily ridership has increased 3.7 0 steadily at a CAGR of xxx for MRT, xxx for LRT and xxx for 2011 (million) 2012 (million) 2013 (million) 2014 (million) buses, between 2011-2014. -

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit

Merdeka Generation Package $100 Top-Up Benefit The Merdeka Generation (MG) One-Time $100 Top-Up will be available from 01 July 2019 onwards. Apart from the top-up locations at the MRT stations and bus interchanges, temporary top-up booths at selected Community Clubs/ Centres will be set up to provide even greater convenience to our MGs with their top ups. a) TransitLink Ticket Offices Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 1 Aljunied MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 2 Ang Mo Kio MRT Station 0800 - 2100 3 Bayfront MRT Station (CCL)* Closed 1200 - 2000 4 Bedok Bus Interchange 1000 - 2000 1000 - 1700 Closed 5 Bedok MRT Station * 1200 - 2000 6 Bishan MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 7 Boon Lay Bus Interchange 0800 - 2100 8 Bugis MRT Station 1000 - 2100 9 Bukit Batok MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 10 Bukit Merah Bus Interchange * 1200 - 1930 11 Changi Airport MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 12 Chinatown MRT Station ~@ 0800 - 2100 13 City Hall MRT Station 0900 - 2100 14 Clementi MRT Station 0800 - 2100 15 Eunos MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 1200 - 1800 Closed 16 Farrer Park MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 17 HarbourFront MRT Station ~ 0800 - 2100 Updated as of 2 July 2019 Operating Hours TransitLink Ticket Offices Public Location Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Holidays 18 Hougang MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 19 Jurong East MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 20 Kranji MRT Station * 1230 - 1930 # 1230 - 1930 ## Closed## 21 Lakeside MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 22 Lavender MRT Station * 1200 - 1930 Closed 23 Novena MRT Station -

Group Review 2018/2019 Group Review 2018/2019 Moving People Enhancing Lives 01

Moving People SMRT CORPORATION LTD Enhancing Lives GROUP REVIEW 2018/2019 GROUP REVIEW 2018/2019 MOVING PEOPLE ENHANCING LIVES 01 SMRT Corporation Developing in Brief 02 Strong Capability Building a Forward-looking Strategy 20 24 OUR VISION Moving People 06 Serving Our Enhancing Lives Community 48 COMPANY PROFILE OUR CORE VALUES CONTENTS SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) is a Integrity SMRT Corporation in Brief Developing Strong Capability public transport service provider. Safety and Service Milestones 02 SMRT Trains 20 Our primary business is to manage Highlights 04 Roads 24 Excellence – SMRT Buses and operate train services on the North-South Line, East-West Line, – SMRT Taxis Building a Forward-looking Strategy – SMRT Automotive Services the Circle Line, the Thomson-East Visit our corporate – Strides Transportation Coast Line (operational in 2019) and website for more Chairman’s Message 06 Engineering 32 the Bukit Panjang Light Rail Transit. information at: CEO’s Message 08 www.smrt.com.sg Experience 36 This is complemented by our bus, Our Focus & Our Four taxi and private hire vehicle services. Join us at Business Groups 10 Our People 42 SMRTCorpSG Board of Directors 12 We have set our core values to be @SMRT_Singapore Senior Management 14 Serving Our Community Integrity, Safety and Service, and SMRT Corporate Social Responsibility 50 Excellence. SMRT is committed to provide safe, reliable and comfortable SMRT Corporation Ltd Ensuring Sound Governance Commuter Engagement 54 service for our commuters. @SMRTSingapore Key Dynamics and Risk Management 16 Awards and Accolades 55 GROUP REVIEW 2018/2019 MOVING PEOPLE ENHANCING LIVES 01 SMRT Corporation Developing in Brief 02 Strong Capability Building a Forward-looking Strategy 20 24 OUR VISION Moving People 06 Serving Our Enhancing Lives Community 48 COMPANY PROFILE OUR CORE VALUES CONTENTS SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) is a Integrity SMRT Corporation in Brief Developing Strong Capability public transport service provider. -

Geotechnical Services

GGeeooAAlllliiaannccee CCoonnssuullttaannttss PPttee LLttdd WHO WE ARE GeoAlliance Consultants Pte Ltd is a specialist ground engineering consultancy established by a group of registered professional engineers in Singapore. Our team has wide hands-on experience in both design and supervision of civil engineering and geotechnical engineering works in Singapore and overseas. Our team members have been involved in projects on the MRT Northeast Line, MRT Circle Line, MRT Downtown Line and Marina Coastal Expressway, and Kim Chuan Sewerage Plant, Changi Outfall in each of their own capacities. Merging our skill sets, experience and resources, we endeavour to provide innovative technical solutions for geotechnical and underground space projects. WHY GeoAlliance Professional Engineers with PE(Civil), PE(Geo) and AC(Geo) registrations Experience with local building authority, international consultants and contractors “Can-do” attitude Innovative, cost-effective and practical solutions Efficient and excellent services Reliable business & project partner Potential integration with client’s team WHAT WE DO Our team has an extensive range of knowledge and experience. Professional services by GeoAlliance Consultants Pte Ltd can be provided at all stages of project implementation, including: Planning Analysis and Design Feasibility Studies Geotechnical Interpretative Studies Planning of Geotechnical Investigations Earth Retaining Structures (ERSS or Engineering Support for Project Tenders TERS) Preliminary Designs for Cost Estimates Geotechnical -

Subway Productivity, Performance, and Profitability: Tale of Five Cities

Photo: Trevor Logan, Jr. Subway Productivity, Performance, and T R A N S I T Profitability: Tale of Five Cities Hong Kong, Singapore, NYC Subway Kuala Lumpur, Taipei, Train New York City Alla Reddy Alex Lu, Ted Wang System Data & Research Operations Planning New York City Transit Authority Presented at the 89th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board Washington D.C. (2010) Notice: Opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the New York City Transit official policy or position of MTA New York City Transit, TCRP, or any otherTRB organization. Paper #10-0487 1 Comparative Analysis • Transit system scope, density, design affect productivity, profitability, performance • History, urban geography, governance, social context, regulations impact transit design and scope • Comparisons should explain reasons for differences • Transit design philosophies – New York: high-service, widespread, represented, and equitable – Hong Kong: “prudent commercial” – Taipei, Singapore: focus on real estate development New York City Transit TRB Paper #10-0487 2 Productivity: Density and Utilization City Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong Singapore Taipei New York (1997) (2007) (2008) Stations 44 52 80 51 69 468 Passengers 27 18 14 8 8 7 per Route Mile Subway Non- $248m $1.3 bn $1.2 bn $59m $36m $161m Fare Revenue • Hong Kong is densest, 120 Area of rectangles proportional to passenger-miles carried by each system (see Pushkarev, Zupan, and Cumella, 1980) even after absorbing 100 commuter rail; New 80 -

Programme Schedule

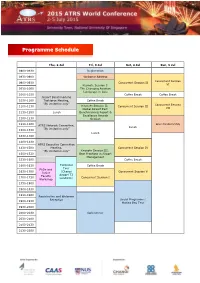

Programme Schedule Thu, 2 Jul Fri, 3 Jul Sat, 4 Jul Sun, 5 Jul 0800-0830 Registration 0830-0900 Welcome Address Concurrent Session 0900-0930 Concurrent Session II Keynote Session I: VI 0930-1000 The Changing Aviation Landscape in Asia 1000-1030 Coffee Break Coffee Break Airport Benchmarking 1030-1100 Taskforce Meeting, Coffee Break "By invitation only" Concurrent Session 1100-1130 Keynote Session II: Concurrent Session III Global Airport Perf. VII 1130-1200 Lunch Benchmarking Report & Excellence Awards 1200-1230 Session 1230-1300 ATRS Network Committee, General Assembly Lunch 1300-1330 "By invitation only" Lunch 1330-1400 1400-1430 ATRS Executive Committee 1430-1500 Meeting, Concurrent Session IV "By invitation only" Keynote Session III: 1500-1530 Best Practices in Airport Management 1530-1600 Coffee Break 1600-1630 Technical Coffee Break PhDs and Tour 1630-1700 Junior (Changi Concurrent Session V Airport T3 1700-1730 Faculty Concurrent Session I Workshop Landside) 1730-1800 1800-1830 1830-1900 Registration and Welcome Social Programme: 1900-1930 Reception Marina Bay Tour 1930-2000 2000-2030 Gala Dinner 2030-2100 2100-2130 2130-2200 Concurrent Sessions Overview Friday, 3th July 16:30-18:00 Concurrent Session 1 Session 4-C Air Transport Demand Session 1-A Singapore Air Logistics Panel Seminar Room 5/6 Session Seminar Room 12 Session 4-D Airline Strategy, Management Session 1-B Airport Strategy, Management Seminar Room 7/8 and Operations and Operations Seminar Room 3/4 Session 4-E Environmental Issues in Air Session 1-C Seminar Room 9 Transport -

OUR PEOPLE, YOUR JOURNEY SMRT Corporation Ltd GROUP REVIEW 2019/2020 ABOUT SMRT CORPORATION SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) Is a Public Transport Service Provider

OUR PEOPLE, YOUR JOURNEY SMRT Corporation Ltd GROUP REVIEW 2019/2020 ABOUT SMRT CORPORATION SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) is a public transport service provider. Our primary business is to manage and operate train services on the North-South Line, East-West Line, the Circle Line, the new Thomson-East Coast Line and the Bukit Panjang Light Rail Transit. This is complemented by our bus, taxi and private hire vehicle services. We have set our core values to be Integrity, Service & Safety and Excellence. SMRT is committed to provide safe, reliable and comfortable service for our commuters. VISION Moving People Enhancing Lives MISSION To deliver a public transport service that is safe, reliable and commuter-centred OUR CORE VALUES Visit our corporate website for more Integrity information at: www.smrt.com.sg JOIN US AT: Service and Safety SMRTCorpSG @SMRT_Singapore Excellence smrt SMRT Corporation Ltd @smrtsingapore 1 OUR VISION OPERATIONAL & SERVICE CONTENTS EXCELLENCE 19 Trains Engineering SMRT CORPORATION 25 IN BRIEF 31 Roads – Buses Milestones 03 – Taxis – Automotive Services Highlights 05 – Strides Transportation 07 Awards and Accolades 41 Experience 49 Safety and Security BUILDING A FORWARD-LOOKING 55 Our People STRATEGY 09 Chairman’s Message GOVERNANCE 11 Group CEO’s Message 59 Ensuring Sound Governance 13 Our Focus & 61 Risk Management Framework Our Four Business Groups 15 Board of Directors ENGAGING OUR COMMUNITY 17 Senior Management 65 WeCare for Commuters 71 Corporate Social Responsibility CONTENTS 2 SMRT CORPORATION IN BRIEF MILESTONES -

Tenant's Fitting-Out Manual

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial (Shops) Tenants The X Collective Pte Ltd 2 Tanjong Katong Road #08-01, Tower 3, Paya Lebar Quarter Singapore 437161 Tel : 65 6331 1333 www.smrt.com.sg While every reasonable care has been taken to provide the information in this Fitting-Out Manual, SMRT makes no representation whatsoever on the accuracy of the information contained which is subject to change without prior notice. SMRT reserves the right to make amendments to this Fitting-Out Manual from time to time as necessary. SMRT accepts no responsibility and/or liability whatsoever for any reliance on the information herein and/or damage howsoever occasioned. 04/2019 (Ver 4.0) 1 Contents FOREWORD ………..…………….……….……………………………...………………… 4 GENERAL INFORMATION ………………………………………………………………… 5 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS / DEFINITIONS ………………..................................... 6 1. OVERVIEW ….……………..…………………………….…………………..…… 7 2. FIT-OUT PROCEDURES ……………………………..………………..…..…... 8 2.1. Stage 1 – Introductory and Pre Fit-Out Briefing …….…………………………… 8 2.2. Stage 2 – Submission of Fit-Out Proposal for Preliminary Review …….…… 8 2.3. Stage 3 – Resubmission of Fit-Out Proposal After Preliminary Review …........11 2.4. Stage 4 – Site Possession …..……………………………………..…….……….. 11 2.5. Stage 5 – Fitting-Out Work ………………………………………………..………. 12 2.6. Stage 6 – Post Fit-Out Inspection and Submission of As-Built Drawings….. 14 3. TENANCY DESIGN CRITERIA & GUIDELINES …..……………..……………. 15 3.1 Design Criteria for Shop Components ……….………………………….….…… 15 3.2 Food & Beverage Units (Including Cafes and Restaurants) ………..……..….. 24 3.3 Design Control Area (DCA) …………………………………………..……..……. 26 4. FITTING-OUT CONTRACTOR GUIDELINES …..……………………………. 27 4.1 Building and Structural Works …………………………………………..……. 27 4.2 Mechanical and Electrical Services ….………………………………….…. 28 4.3 Public Address (PA) System ……….……………………………………….. 39 4.4 Sub-Directory Signage ……..…………………………………………………. -

Mind the Gap: How Economically Disadvantaged Students Navigate Elite Private Schools in Ontario

MIND THE GAP: HOW ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS NAVIGATE ELITE PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN ONTARIO by William George Peat A dissertation submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by William George Peat 2020 MIND THE GAP: HOW ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS NAVIGATE ELITE PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN ONTARIO William George Peat Doctor of Philosophy Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education University of Toronto 2020 Abstract “Mind the gap” is a qualitative study rooted in the sociology of education, dealing with educational inequality in Canada. It asked: what is the experience of working-class students in elite secondary schools, and are the benefits of achieving social mobility worth the costs? In a country whose populace has long seen itself as middle class, but where social inequality is a growing concern and social mobility increasingly rare, the study examined the journey of three working-class students seeking to become upwardly mobile by attending elite private schools in Ontario. The study examined their experiences, and employed a combination of semistructured, in-depth interviews, and follow-up conversations. It also drew on relationships that formed as a result of them, as well as on the researcher’s knowledge of the culture of the schools the students attended. In addition, it drew upon the lived experience of the researcher, who shares similar elements of the participants’ socioeconomic background. The data produced was used to develop literary and visual portraits. The process was collaborative and enabled the participants to become co-creators in the creation of their portraits, which were subject to analyses. -

Moving Stories 2.0.Pdf

GROWING: RISING TO THE CHALLENGE 94 Events That Shaped Us 95 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1986: Collapse of Hotel New World 96 1993: The First Major MRT Incident 97 2003: SARS Crisis 98 2004: Exercise Northstar 99 2010: Acts of Vandalism 100 BEGINNING: THE RAIL DEVELOPMENT 1 2011: MRT Disruptions 100 CONNECTING: OUR SMRT FAMILY 57 The Rail Progress 2 2012: Bus Captains’ Strike 102 The Early Days 4 One Family 58 2015: Remembering Our Founding Father 104 Opening of the Rail Network 10 One Identity 59 2015: Celebrating SG50 106 Completion of the North-South and East-West Lines 15 A Familiar Place 60 2016: 22 March Fatal Accident 107 INNOVATING: MOVING WITH THE TIMES 110 Woodlands Extension 22 A Familiar Face 61 2017: Flooding in Tunnel 108 Operations to Innovation 111 Bukit Panjang Light Rail Transit 24 National Day Parade 2004 62 2017: Train Collision at Joo Koon MRT Station 109 Operating for Tomorrow 117 Keeping It in the Family 64 Beyond Our Network & Borders 120 Love is in the Air 66 Footprint in the Urban Mobility Space 127 Esprit de Corps 68 TRANSFORMING: TRAVEL REDEFINED 26 A Greener Future 129 Remember the Mascots? 74 SMRT Corporation Ltd 27 Stretching Our Capability 77 TIBS Merger 30 Engaging Our Community 80 An Expanding Network 35 Fare Payment Evolution 42 Tracking Improvements 50 More Than Just a Station 53 SMRT Institute 56 VISION 1 Moving People, Enhancing Lives MISSION In 2017, SMRT Corporation Ltd (SMRT) celebrates 30 years of Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) operations. To be the people’s choice by delivering a world-class transport service and Delivering a world-class transport service that is safe, reliable and customer-centric is at the lifestyle experience that is safe, heart of what we do.