Randomised Phase 2 Study of Maintenance Linsitinib

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Test That Measures Real-Time HER2 Signaling Function in Live Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Primary Cells Yao Huang1, David J

Huang et al. BMC Cancer (2017) 17:199 DOI 10.1186/s12885-017-3181-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Development of a test that measures real-time HER2 signaling function in live breast cancer cell lines and primary cells Yao Huang1, David J. Burns1, Benjamin E. Rich1, Ian A. MacNeil1, Abhijit Dandapat1, Sajjad M. Soltani1, Samantha Myhre1, Brian F. Sullivan1, Carol A. Lange2, Leo T. Furcht3 and Lance G. Laing1* Abstract Background: Approximately 18–20% of all human breast cancers have overexpressed human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Standard clinical practice is to treat only overexpressed HER2 (HER2+) cancers with targeted anti-HER2 therapies. However, recent analyses of clinical trial data have found evidence that HER2-targeted therapies may benefit a sub-group of breast cancer patients with non-overexpressed HER2. This suggests that measurement of other biological factors associated with HER2 cancer, such as HER2 signaling pathway activity, should be considered as an alternative means of identifying patients eligible for HER2 therapies. Methods: A new biosensor-based test (CELxTM HSF) that measures HER2 signaling activity in live cells is demonstrated using a set of 19 human HER2+ and HER2– breast cancer reference cell lines and primary cell samples derived from two fresh patient tumor specimens. Pathway signaling is elucidated by use of highly specific agonists and antagonists. The test method relies upon well-established phenotypic, adhesion-related, impedance changes detected by the biosensor. Results: The analytical sensitivity and analyte specificity of this method was demonstrated using ligands with high affinity and specificity for HER1 and HER3. The HER2-driven signaling quantified ranged 50-fold between the lowest and highest cell lines. -

Therapeutic Targeting of the IGF Axis

cells Review Therapeutic Targeting of the IGF Axis Eliot Osher and Valentine M. Macaulay * Department of Oncology, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7DQ, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1865617337 Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 9 August 2019; Published: 14 August 2019 Abstract: The insulin like growth factor (IGF) axis plays a fundamental role in normal growth and development, and when deregulated makes an important contribution to disease. Here, we review the functions mediated by ligand-induced IGF axis activation, and discuss the evidence for the involvement of IGF signaling in the pathogenesis of cancer, endocrine disorders including acromegaly, diabetes and thyroid eye disease, skin diseases such as acne and psoriasis, and the frailty that accompanies aging. We discuss the use of IGF axis inhibitors, focusing on the different approaches that have been taken to develop effective and tolerable ways to block this important signaling pathway. We outline the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, and discuss progress in evaluating these agents, including factors that contributed to the failure of many of these novel therapeutics in early phase cancer trials. Finally, we summarize grounds for cautious optimism for ongoing and future studies of IGF blockade in cancer and non-malignant disorders including thyroid eye disease and aging. Keywords: IGF; type 1 IGF receptor; IGF-1R; cancer; acromegaly; ophthalmopathy; IGF inhibitor 1. Introduction Insulin like growth factors (IGFs) are small (~7.5 kDa) ligands that play a critical role in many biological processes including proliferation and protection from apoptosis and normal somatic growth and development [1]. IGFs are members of a ligand family that includes insulin, a dipeptide comprised of A and B chains linked via two disulfide bonds, with a third disulfide linkage within the A chain. -

TE INI (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub

US 20200187851A1TE INI (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No .: US 2020/0187851 A1 Offenbacher et al. (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 18 , 2020 ( 54 ) PERIODONTAL DISEASE STRATIFICATION (52 ) U.S. CI. AND USES THEREOF CPC A61B 5/4552 (2013.01 ) ; G16H 20/10 ( 71) Applicant: The University of North Carolina at ( 2018.01) ; A61B 5/7275 ( 2013.01) ; A61B Chapel Hill , Chapel Hill , NC (US ) 5/7264 ( 2013.01 ) ( 72 ) Inventors: Steven Offenbacher, Chapel Hill , NC (US ) ; Thiago Morelli , Durham , NC ( 57 ) ABSTRACT (US ) ; Kevin Lee Moss, Graham , NC ( US ) ; James Douglas Beck , Chapel Described herein are methods of classifying periodontal Hill , NC (US ) patients and individual teeth . For example , disclosed is a method of diagnosing periodontal disease and / or risk of ( 21) Appl. No .: 16 /713,874 tooth loss in a subject that involves classifying teeth into one of 7 classes of periodontal disease. The method can include ( 22 ) Filed : Dec. 13 , 2019 the step of performing a dental examination on a patient and Related U.S. Application Data determining a periodontal profile class ( PPC ) . The method can further include the step of determining for each tooth a ( 60 ) Provisional application No.62 / 780,675 , filed on Dec. Tooth Profile Class ( TPC ) . The PPC and TPC can be used 17 , 2018 together to generate a composite risk score for an individual, which is referred to herein as the Index of Periodontal Risk Publication Classification ( IPR ) . In some embodiments , each stage of the disclosed (51 ) Int. Cl. PPC system is characterized by unique single nucleotide A61B 5/00 ( 2006.01 ) polymorphisms (SNPs ) associated with unique pathways , G16H 20/10 ( 2006.01 ) identifying unique druggable targets for each stage . -

WO 2013/152252 Al 10 October 2013 (10.10.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/152252 Al 10 October 2013 (10.10.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: STEIN, David, M.; 1 Bioscience Park Drive, Farmingdale, Λ 61Κ 38/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/517 (2006.01) NY 11735 (US). MIGLARESE, Mark, R.; 1 Bioscience A61K 39/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/713 (2006.01) Park Drive, Farmingdale, NY 11735 (US). A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) (74) Agents: STEWART, Alexander, A. et al; 1 Bioscience A61K 31/404 (2006 ) A61P 35/04 (2006.01) Park Drive, Farmingdale, NY 11735 (US). A61K 31/4985 (2006.01) A61K 31/53 (2006.01) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (21) International Application Number: available): AE, AG, AL, AM, PCT/US2013/035358 kind of national protection AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (22) International Filing Date: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, 5 April 2013 (05.04.2013) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, English (25) Filing Language: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (26) Publication Language: English ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (30) Priority Data: RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, 61/621,054 6 April 2012 (06.04.2012) US TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, (71) Applicant: OSI PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC [US/US]; ZM, ZW. -

IGF-1R) Signaling Loop Is Involved in Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

cancers Article A Yes-Associated Protein (YAP) and Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF-1R) Signaling Loop Is Involved in Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Mai-Huong T. Ngo 1,2, Sue-Wei Peng 2,3,†, Yung-Che Kuo 3,† , Chun-Yen Lin 4 , Ming-Heng Wu 5,6,7 , Chia-Hsien Chuang 4, Cheng-Xiang Kao 1 , Han-Yin Jeng 3 , Gee-Way Lin 2,8 , Thai-Yen Ling 9, Te-Sheng Chang 10,11,* and Yen-Hua Huang 1,2,3,5,7,12,13,14,15,* 1 International Ph.D. Program for Cell Therapy and Regeneration Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] (M.-H.T.N.); [email protected] (C.-X.K.) 2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Cell Biology, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] (S.-W.P.); [email protected] (G.-W.L.) 3 TMU Research Center of Cell Therapy and Regeneration Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] (Y.-C.K.); [email protected] (H.-Y.J.) 4 Institute of Information Science, Academia Sinica, Taipei 11529, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-Y.L.); [email protected] (C.-H.C.) 5 The Ph.D. Program for Translational Medicine, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Graduate Institute of Biomedical Informatics, College of Medical Science and Technology, Citation: Ngo, M.-H.T.; Peng, S.-W.; Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan Kuo, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, M.-H.; 7 International Ph.D. -

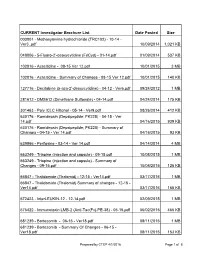

Prepared by CTEP 4/1/2016 Page 1 of 8 CURRENT Investigator Brochure List Date Posted Size

CURRENT Investigator Brochure List Date Posted Size 003801 - Methoxyamine hydrochloride (TRC102) - 10-14 - Ver3..pdf 10/09/2014 1,021 KB 048006 - 5-Fluoro-2’-deoxycytidine (FdCyd) - 01-14.pdf 01/09/2014 537 KB 102816 - Azacitidine - 08-15 Ver 12.pdf 10/01/2015 3 MB 102816 - Azacitidine - Summary of Changes - 08-15 Ver 12.pdf 10/01/2015 140 KB 127716 - Decitabine (5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine) - 04-12 - Ver6.pdf 09/24/2012 1 MB 281612 - DMS612 (Dimethane Sulfonate) - 04-14.pdf 04/24/2014 175 KB 301463 - Poly ICLC Hiltonol - 05-14 - Ver9.pdf 08/26/2014 412 KB 630176 - Romidepsin (Depsipeptide; FK228) - 04-15 - Ver 14.pdf 04/16/2015 939 KB 630176 - Romidepsin (Depsipeptide; FK228) - Summary of Changes - 04-15 - Ver 14.pdf 04/16/2015 93 KB 639966 - Perifosine - 03-14 - Ver 14.pdf 04/14/2014 4 MB 663249 - Triapine (injection and capsule) - 09-15.pdf 10/08/2015 1 MB 663249 - Triapine (injection and capsule) - Summary of Changes - 09-15.pdf 10/08/2015 125 KB 66847 - Thalidomide (Thalomid) - 12-15 - Ver14.pdf 03/17/2016 1 MB 66847 - Thalidomide (Thalomid) Summary of changes - 12-15 - Ver14.pdf 03/17/2016 165 KB 672423 - InterLEUKIN-12 - 12-14.pdf 02/09/2015 1 MB 676422 - Immunotoxin LMB-2 (Anti-Tac(Fv)-PE-38) - 05-15.pdf 06/02/2015 466 KB 681239 - Bortezomib - 06-15 - Ver18.pdf 08/11/2015 1 MB 681239 - Bortezomib - Summary Of Changes - 06-15 - Ver18.pdf 08/11/2015 153 KB Prepared by CTEP 4/1/2016 Page 1 of 8 CURRENT Investigator Brochure List Date Posted Size 683864 - Temsirolimus (PF-05208748) - 12-15.pdf 01/28/2016 909 KB 683864 - Temsirolimus (PF-05208748) -

Ping Chi, MD, Ph.D

New Advances in Research and Clinical Insights in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) Ping Chi, M.D., Ph.D. Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program (HOPP) & Department of Medicine, Sarcoma Medical Oncology Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center May 24, 2017 Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) Management • Surgery mainstay treatment • Recurrence or metastatic disease - fatal • Refractory to chemotherapy and radiation • ~5,000 cases diagnosed per year in the US. • One of the most common subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas, the most common mesenchymal neoplasm in the GI tract. • Can arise anywhere from the entire GI tract; stomach is the most common primary site (2/3), then small bowel (1/4), esophagus/colon/rectum (the rest). •Peak incidence 50-65 year old. •Familial syndromes Pre-KIT ERA: GIST- A clinicopathological challenge GIST has broad morphological spectrum Sclerosing Palisaded-vacuolated •Difficult to diagnose! Spindle •Difficult to treat! Hypercellular Sarcomatous Clinicopathologically distinct entity! Sclerosing dyscohesive pattern Epithelioid Hypercellular Sarcomatous Miettinen, M. and Lasota, Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006 GIST originates from ICC and highly expresses KIT • Originates from the Interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICCs) of the GI tract • Characterized by KIT positive IHC and activating mutations in KIT or PDGFRA… Interstitial Cell of Cajal (ICC)- GIST of stomach Pacemaker cells of the GI tract H&E α-KIT Hirota, S., et al., Science, 1998 A Paradigm: Normal ICC development vs. GIST Normal ICC development GIST KIT/PDGFRA mutation External KIT/PDGFRA stimuli P P Signaling Aberrant signaling STAT STAT PI3K MAPK PI3K MAPK ETV1 ON ON/OFF TFs TF Chromatin TF Molecular characterization of GIST Corless et al, Nat Rev Cancer, 2011 Imatinib (Gleevec) in GIST • Activity – Abl kinase, KIT, PDGFRA TTF OS Historical OS with Doxorubicin Imatinib-FDA approved as 1st line therapy for GIST 2002! Challenges - Imatinib resistance in GIST 14% - Primary resistance; 50% - Develop imatinib resistance after 2 years Corless et al, NRC, 2011 Resistance Mechanisms: 1. -

Download This PDF File

Cancer Biol Med 2021. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0560 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Systematic screening reveals synergistic interactions that overcome MAPK inhibitor resistance in cancer cells Yu Yu1*, Minzhen Tao2*, Libin Xu3, Lei Cao4, Baoyu Le5, Na An5, Jilin Dong5, Yajie Xu5, Baoxing Yang5, Wei Li5, Bing Liu5, Qiong Wu6, Yinying Lu7, Zhen Xie2, Xiaohua Lian1 1Department of Cell Biology, Basic Medical College, Army Medical University (Third Military Medical University), Chongqing 400038, China; 2MOE Key Laboratory of Bioinformatics and Bioinformatics Division, Center for Synthetic and System Biology, Department of Automation, Beijing National Research Center for Information Science and Technology, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; 3National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China; 4Department of Thoracic Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100730, China; 5Beijing Syngentech Co., Ltd, Beijing 102206, China; 6School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; 7The Comprehensive Liver Cancer Center, The 5th Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100039, China ABSTRACT Objective: Effective adjuvant therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to overcome MAPK inhibitor (MAPKi) resistance, which is one of the most common forms of resistance that has emerged in many types of cancers. Here, we aimed to systematically identify the genetic interactions underlying MAPKi resistance, and to further investigate the mechanisms that produce the genetic interactions that generate synergistic MAPKi resistance. Methods: We conducted a comprehensive pair-wise sgRNA-based high-throughput screening assay to identify synergistic interactions that sensitized cancer cells to MAPKi, and validated 3 genetic combinations through competitive growth, cell viability, and spheroid formation assays. -

Original Article a Preclinical Report of a Cobimetinib-Inspired Novel

Am J Cancer Res 2021;11(6):2590-2617 www.ajcr.us /ISSN:2156-6976/ajcr0131974 Original Article A preclinical report of a cobimetinib-inspired novel anticancer small-molecule scaffold of isoflavones, NSC777213, for targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR/MEK in multiple cancers Bashir Lawal1,2*, Wen-Cheng Lo3,4,5*, Ntlotlang Mokgautsi1,2, Maryam Rachmawati Sumitra1,2, Harshita Khedkar1,2, Alexander TH Wu6,7,8,9, Hsu-Shan Huang1,2,10,11 1PhD Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University and Academia Sinica, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 2Graduate Institute for Cancer Biology & Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 3Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 4Department of Neurosurgery, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 5Taipei Neuroscience Institute, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 6TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 7The PhD Program of Translational Medicine, College of Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 8Clinical Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; 9Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei 11490, Taiwan; 10School of Pharmacy, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei 11490, -

Product Data Sheet

Inhibitors Product Data Sheet Linsitinib • Agonists Cat. No.: HY-10191 CAS No.: 867160-71-2 Molecular Formula: C₂₆H₂₃N₅O • Molecular Weight: 421.49 Screening Libraries Target: IGF-1R; Insulin Receptor Pathway: Protein Tyrosine Kinase/RTK Storage: Powder -20°C 3 years 4°C 2 years In solvent -80°C 6 months -20°C 1 month SOLVENT & SOLUBILITY In Vitro DMSO : 50 mg/mL (118.63 mM; Need ultrasonic) Mass Solvent 1 mg 5 mg 10 mg Concentration Preparing 1 mM 2.3725 mL 11.8627 mL 23.7254 mL Stock Solutions 5 mM 0.4745 mL 2.3725 mL 4.7451 mL 10 mM 0.2373 mL 1.1863 mL 2.3725 mL Please refer to the solubility information to select the appropriate solvent. In Vivo 1. Add each solvent one by one: 10% DMSO >> 40% PEG300 >> 5% Tween-80 >> 45% saline Solubility: ≥ 2.08 mg/mL (4.93 mM); Clear solution 2. Add each solvent one by one: 10% DMSO >> 90% (20% SBE-β-CD in saline) Solubility: ≥ 2.08 mg/mL (4.93 mM); Clear solution BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY Description Linsitinib (OSI-906) is a potent, selective and orally bioavailable dual inhibitor of the IGF-1 receptor and insulin receptor (IR) [1] with IC50s of 35 and 75 nM, respectively . IC₅₀ & Target IC50: 35 nM (IGF-1R), 75 nM (InsR)[1] In Vitro Linsitinib inhibits IGF-1R autophosphorylation and activation of the downstream signaling proteins Akt, ERK1/2 and S6 kinase with IC50 of 0.028 to 0.13 μM. Linsitinib enables an intermediate conformation of the target protein through interactions with the C-helix. -

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Solid Tumors in the Past 20 Years (2001–2020) Liling Huang†, Shiyu Jiang† and Yuankai Shi*

Huang et al. J Hematol Oncol (2020) 13:143 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00977-0 REVIEW Open Access Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001–2020) Liling Huang†, Shiyu Jiang† and Yuankai Shi* Abstract Tyrosine kinases are implicated in tumorigenesis and progression, and have emerged as major targets for drug discovery. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) inhibit corresponding kinases from phosphorylating tyrosine residues of their substrates and then block the activation of downstream signaling pathways. Over the past 20 years, multiple robust and well-tolerated TKIs with single or multiple targets including EGFR, ALK, ROS1, HER2, NTRK, VEGFR, RET, MET, MEK, FGFR, PDGFR, and KIT have been developed, contributing to the realization of precision cancer medicine based on individual patient’s genetic alteration features. TKIs have dramatically improved patients’ survival and quality of life, and shifted treatment paradigm of various solid tumors. In this article, we summarized the developing history of TKIs for treatment of solid tumors, aiming to provide up-to-date evidence for clinical decision-making and insight for future studies. Keywords: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Solid tumors, Targeted therapy Introduction activation of tyrosine kinases due to mutations, translo- According to GLOBOCAN 2018, an estimated 18.1 cations, or amplifcations is implicated in tumorigenesis, million new cancer cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths progression, invasion, and metastasis of malignancies. occurred in 2018 worldwide [1]. Targeted agents are In addition, wild-type tyrosine kinases can also func- superior to traditional chemotherapeutic ones in selec- tion as critical nodes for pathway activation in cancer. -

Characteristics of Lung Cancers Harboring NRAS Mutations

Published OnlineFirst March 20, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3173 Clinical Cancer Predictive Biomarkers and Personalized Medicine Research Characteristics of Lung Cancers Harboring NRAS Mutations Kadoaki Ohashi1, Lecia V. Sequist6,7, Maria E. Arcila8, Christine M. Lovly1, Xi Chen2, Charles M. Rudin10, Teresa Moran11, David Ross Camidge12, Cindy L. Vnencak-Jones4, Lynne Berry3, Yumei Pan1, Hidefumi Sasaki13, Jeffrey A. Engelman6,7, Edward B. Garon14, Steven M. Dubinett14, Wilbur A. Franklin12, Gregory J. Riely9, Martin L. Sos15,16,17, Mark G. Kris9, Dora Dias-Santagata5, Marc Ladanyi8, Paul A. Bunn Jr12, and William Pao1 Abstract Purpose: We sought to determine the frequency and clinical characteristics of patients with lung cancer harboring NRAS mutations. We used preclinical models to identify targeted therapies likely to be of benefit against NRAS-mutant lung cancer cells. Experimental Design: We reviewed clinical data from patients whose lung cancers were identified at six institutions or reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) to harbor NRAS mutations. Six NRAS-mutant cell lines were screened for sensitivity against inhibitors of multiple kinases (i.e., EGFR, ALK, MET, IGF-1R, BRAF, PI3K, and MEK). Results: Among 4,562 patients with lung cancers tested, NRAS mutations were present in 30 (0.7%; 95% confidence interval, 0.45%–0.94%); 28 of these had no other driver mutations. 83% had adenocarcinoma histology with no significant differences in gender. While 95% of patients were former or current smokers, smoking-related G:C>T:A transversions were significantly less frequent in NRAS-mutated lung tumors than KRAS-mutant non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC; NRAS: 13% (4/30), KRAS: 66% (1772/2733), P < 0.00000001].