An Efferent Component in the Visual Perception of Direction and Extent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Illusions “What You See Is Not What You Get”

Optical Illusions “What you see is not what you get” The purpose of this lesson is to introduce students to basic principles of visual processing. Much of the lesson revolves around the use of visual illusions and interactive demonstrations with the students. The overarching theme of this lesson is that perception and sensation are not necessarily the same, and that optical illusions are a way for us to study the way that our visual system works. Furthermore, there are cells in the visual system that specifically respond to particular aspects of visual stimuli, and these cells can become fatigued. Grade Level: 3-12 Presentation time: 15-30 minutes, depending on which activities are chosen Lesson plan organization: Each lesson plan is divided into three sections: Introducing the lesson, Conducting the lesson, and Concluding the lesson. Each lesson has specific principles with associated figures, class discussion (D), and learning activities (A). This lesson plan is provided by the Neurobiology and Behavior Community Outreach Team at the University of Washington: http://students.washington.edu/watari/neuroscience/k12/LessonPlans.html 1 Materials: Computer to display some optical illusions (optional) Checkerboard illusion: Provided on page 8 or available online with explanation at http://web.mit.edu/persci/people/adelson/checkershadow_illusion.html Lilac chaser movie: http://www.scientificpsychic.com/graphics/ as an animated gif or http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/col_lilacChaser/index.html as Adobe Flash and including scientific explanation -

Exploring 3D Stereo with Incremental Rehearsal and Partial Occlusion to Instigate and Modulate Smooth Pursuit and Saccade Responses in Baseball Batting

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Computational Modeling & Simulation Computational Modeling & Simulation Engineering Theses & Dissertations Engineering Summer 2016 Toward Simulation-Based Training Validation Protocols: Exploring 3d Stereo with Incremental Rehearsal and Partial Occlusion to Instigate and Modulate Smooth Pursuit and Saccade Responses in Baseball Batting Ricardo A. Roca Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/msve_etds Part of the Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Roca, Ricardo A.. "Toward Simulation-Based Training Validation Protocols: Exploring 3d Stereo with Incremental Rehearsal and Partial Occlusion to Instigate and Modulate Smooth Pursuit and Saccade Responses in Baseball Batting" (2016). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Computational Modeling & Simulation Engineering, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/hvse-ts08 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/msve_etds/3 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Computational Modeling & Simulation Engineering at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computational Modeling & Simulation Engineering Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARD SIMULATION-BASED TRAINING VALIDATION PROTOCOLS: EXPLORING 3D STEREO WITH INCREMENTAL REHEARSHAL AND PARTIAL OCCLUSION TO INSTIGATE AND MODULATE SMOOTH PURSUIT AND SACCADE RESPONSES IN BASEBALL BATTING by Ricardo A. Roca B.S.E. May 1986, Tulane University M.S. January 2002, George Mason University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY MODELING & SIMULATION OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2016 Approved by: Stacie I. Ringleb (Director) Michel A. Audette (Member) Lance M. -

Bridget Riley Valentine Op Art Heart

Op Art: Lesson Bridget Riley 6 Valentine Op Art Heart • How do 2D geometric shapes invoke movement? • How can the manipulation of geometric shapes and patterns create dimension in 2D art? LESSON OVERVIEW/OBJECTIVES Students will learn about the artist Bridget Riley and her work in Optical Art (Op Art). Riley (1931-present) is a British artist known for bringing about the Op Art movement. Op Art is a style of visual art that uses precise patterns and color to create optical illusions. Op art works are abstract, with many better known pieces created in black and white. Typically, they give the viewer the impression of movement, hidden images, flashing and vibrating patterns, or of swelling or warping. After learning about Bridget Rily and the Op Art movement, students will create an Op Art heart and background for Valentine’s Day. KEY IDEAS THAT CONNECT TO VISUAL ARTS CORE CURRICULUM: Based on Utah State Visual Arts Core Curriculum Requirements (3rd Grade) Strand: CREATE (3.V.CR.) Students will generate artistic work by conceptualizing, organizing, and completing their artistic ideas. They will refine original work through persistence, reflection, and evaluation. Standard 3.V.CR.1: Elaborate on an imaginative idea and apply knowledge of available resources, tools, and technologies to investigate personal ideas through the art-making process. Standard 3.V.CR.2: Create a personally satisfying artwork using a variety of artistic processes and materials. Standard 3.V.CR.3: Demonstrate an understanding of the safe and proficient use of materials, tools and equipment for a variety of artistic processes. -

Op Art Learning Targets

Op Art Learning Targets Students will be able to develop and use criteria to evaluate craftsmanship in an artwork. Students will use elements and principles to organize the composition in his or her own artwork. How will hit these targets? Discuss craftsmanship Review Elements and Principles PowerPoint Presentation Practice drawing Project: Optical Illusion drawing So what is “craftsmanship”? “craftsmanship” skill in a particular craft the quality of design and work shown in something made by hand; artistry “craftsmanship” skill in a particular craft the quality of design and work shown in something made by hand; artistry. Elements and Principles Elements of art: Principles of • Line Design: • Color • Rhythm • Value • Movement • Shape • Pattern • Form • Balance • Texture • Contrast • Space • Emphasis • Unity Optical Illusions Back in 1915, a cartoonist named W.E. Hill first published this drawing. It's hard to see what it's supposed to be. Is it a drawing of a pretty young girl looking away from us? Or is it an older woman looking down at the floor? Optical Illusions Well, it's both. PERCEPTION: a The key is way of regarding, perception and understanding, or what you expect interpreting something; a to see. mental impression Optical Illusions This simple line drawing is titled, "Mother, Father, and daughter" (Fisher, 1968) because it contains the faces of all three people in the title. How many faces can you find? Optical Illusion: something that deceives/confuses the eye/brain by appearing to be other than it is Optical Illusions Optical Art is a mathematically- oriented form of (usually) Abstract art. It uses repetition of simple forms and colors to create vibrating effects, patterns, an exaggerated sense of depth, foreground- background confusion, and other visual effects. -

Persistence of Vision: the Value of Invention in Independent Art Animation

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Kinetic Imaging Publications and Presentations Dept. of Kinetic Imaging 2006 Persistence of Vision: The alueV of Invention in Independent Art Animation Pamela Turner Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/kine_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Copyright © The Author. Originally presented at Connectivity, The 10th ieB nnial Symposium on Arts and Technology at Connecticut College, March 31, 2006. Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/kine_pubs/3 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Kinetic Imaging at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kinetic Imaging Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamela Turner 2220 Newman Road, Richmond VA 23231 Virginia Commonwealth University – School of the Arts 804-222-1699 (home), 804-828-3757 (office) 804-828-1550 (fax) [email protected], www.people.vcu.edu/~ptturner/website Persistence of Vision: The Value of Invention in Independent Art Animation In the practice of art being postmodern has many advantages, the primary one being that the whole gamut of previous art and experience is available as influence and inspiration in a non-linear whole. Music and image can be formed through determined methods introduced and delightfully disseminated by John Cage. Medieval chants can weave their way through hip-hopped top hits or into sound compositions reverberating in an art gallery. -

Do 3D Visual Illusions Work for Immersive Virtual Environments?

Do 3D Visual Illusions Work for Immersive Virtual Environments? Filip Skolaˇ Roman Gluszny Fotis Liarokapis CYENS – Centre of Excellence Solarwinds CYENS – Centre of Excellence Nicosia, Cyprus Brno, Czech Republic Nicosia, Cyprus [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Visual illusions are fascinating because visual per- The majority of visual illusions are generated by two- ception misjudges the actual physical properties of an image or dimensional pictures and their motions [9], [10]. But there are a scene. This paper examines the perception of visual illusions not a lot of visual illusions that make use of three-dimensional in three-dimensional space. Six diverse visual illusions were im- plemented for both immersive virtual reality and monitor based (3D) shapes [11]. Visual illusions are now slowly making their environments. A user-study with 30 healthy participants took appearance in serious games and are unexplored in virtual place in laboratory conditions comparing the perceptual effects reality. Currently, they are usually applied in the fields of brain of the two different mediums. Experimental data were collected games, puzzles and mini games. from both a simple ordering method and electrical activity of the However, a lot of issues regarding the perceptual effects brain. Results showed unexpected outcomes indicating that only some of the illusions have a stronger effect in immersive virtual are not fully understood in the context of digital games. reality, others in monitor based environments while the rest with An overview of electroencephalography (EEG) based brain- no significant effects. computer interfaces (BCIs) and their present and potential Index Terms—virtual reality, visual illusions, perception, hu- uses in virtual environments and games has been recently man factors, games documented [12]. -

Eye and Brain

Eye and Brain We are so familiar with seeing, that it takes a leap of imagination to realize that there are problems to be solved. But consider it. We are given tiny distorted upside-down images in the eyes and we see separate solid objects in surrounding space. From the patterns of stimulation on the retina we percieve the worlds of objects and this is nothing short of a miracle. Richard L. Gregory, Eye and Brain, 1966 Problems to be Solved Organizational Rules of Visual Perception[2] Similarity Organizational Rules of Visual Perception[2] Proximity Organizational Rules of Visual Perception[2] Continuation Organizational Rules of Visual Perception[2] Contour Saliency Object Recognition depends on the separation of foreground and background in a scene[2] Optical Illusion Three level Processing of a Visual Scene[2] Three level Processing of a Visual Scene[2] Low-Level Processing Intermediate Level Processing High-Level Processing How this Vision Process or Interpretation of the world infront of us happens? Vision Processing Constructive Nature Low-level Visual Processing Intermediate-level Visual Processing High-level Visual Processing Vision Processing Constructive Nature Low-level Visual Processing Intermediate-level Visual Processing High-level Visual Processing Eye-Camera Analogy [1] Expectation and Perceptual task play a critical role in what is seen[2] Expectation and Perceptual task play a critical role in what is seen[2] How this constructive process took place? Structure of the Human Eye[2,3] Visual Pathway Visual -

Understanding Optical Illusions

Understanding Optical Illusions Mohit Gupta What are optical illusions? Perception: I see Light (Sensing) Truth: But this is an ! Oracle Optical Illusion in Nature Image Courtesy: http://apollo.lsc.vsc.edu/classes/met130/notes/chapter19/graphics/infer_mirage_road.jpg A Brightness Illusion Different kinds of illusions • Brightness and Contrast Illusions • Twisted Cord Illusions • Color Illusions • Perspective Illusions • Relative Motion Illusions • Illusions of Expressions Lightness Constancy Our Vision System tries to compensate for differences in illumination Why study optical illusions? • Studying how brain is fooled teaches us how it works “Illusions of the senses tell us the truth about perception” [Purkinje] • It makes us happy : Al Seckel Simultaneous Contrast Illusions Low-level Vision Explanation Negative Positive Photo-receptors Photo-receptors Receptive Fields in the Retina - Inhibitory Excitatory Light - + - Light - Low-level Vision Explanation - - - + - - + - Positive - - Negative Gradient Gradient High-level Vision Explanation: Context Less Incident More Incident Illumination Illumination Higher Perceived Lower Perceived Reflectance Reflectance Brightness = Reflectance * Incident Illumination The Hermann grid illusion The Hermann grid: Low level Explanation - - + - - Lateral Inhibition The Hermann grid illusion Focus on one intersection Why does the illusion disappear? Receptive fields are smaller near the fovea (center) of the eye The Waved Grid: No illusion! Scintillating Grids: Straight and Curved Adelson’s checkerboard -

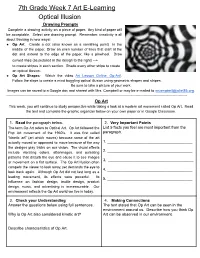

7Th Grade Week 7 Art E-Learning Optical Illusion

7 th Grade Week 7 Art E-Learning Optical Illusion Drawing Prompts Complete a drawing activity on a piece of paper. Any kind of paper will be acceptable. Select one drawing prompt. Remember, creativity is all about thinking in new ways! ● Op Art: Create a dot (also known as a vanishing point) in the middle of the paper. Draw an even number of lines that start at the dot and extend to the edge of the paper, like a pinwheel. Draw curved lines (as pictured in the design to the right) → to create stripes in each section. Shade every other stripe to create an optical illusion. ● Op Art Shapes : Watch the video Art Lesson Online: Op-Art!. Follow the steps to create a mind boggling optical illusion using geometric shapes and stripes. Be sure to take a picture of your work. Images can be saved to a Google doc and shared with Mrs. Campbell or may be e-mailed to m [email protected]. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Op Art This week, you will continue to study perspective while taking a look at a modern art movement called Op Art. Read the text and complete the graphic organizer below on your own paper or in Google Classroom. 1. Read the paragraph below. 2. Very Important Points The term Op Art refers to Optical Art. Op Art followed the List 5 facts you feel are most important from the Pop Art movement of the 1960’s. It was first called paragraph. “kinetic art” (art which moves) because some of the art actually moved or appeared to move because of the way 1. -

Optical Illusion - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Optical illusion - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Try Beta Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history [Hide] Wikipedia is there when you need it — now it needs you. $0.6M USD $7.5M USD Donate Now navigation Optical illusion Main page From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Contents Featured content This article is about visual perception. See Optical Illusion (album) for Current events information about the Time Requiem album. Random article An optical illusion (also called a visual illusion) is characterized by search visually perceived images that differ from objective reality. The information gathered by the eye is processed in the brain to give a percept that does not tally with a physical measurement of the stimulus source. There are three main types: literal optical illusions that create images that are interaction different from the objects that make them, physiological ones that are the An optical illusion. The square A About Wikipedia effects on the eyes and brain of excessive stimulation of a specific type is exactly the same shade of grey Community portal (brightness, tilt, color, movement), and cognitive illusions where the eye as square B. See Same color Recent changes and brain make unconscious inferences. illusion Contact Wikipedia Donate to Wikipedia Contents [hide] Help 1 Physiological illusions toolbox 2 Cognitive illusions 3 Explanation of cognitive illusions What links here 3.1 Perceptual organization Related changes 3.2 Depth and motion perception Upload file Special pages 3.3 Color and brightness -

Introducing the Scintillating Starburst: Illusory Ray Patterns from Spatial Coincidence Detection

Introducing the scintillating starburst: Illusory ray patterns from spatial coincidence detection 1 2 Michael W Karlovich & Pascal Wallisch 1 Recursia Labs. 2 Department of Psychology, New York University Abstract Here, we introduce a novel class of visual illusion, the “Scintillating Starburst”, which features illusory scintillating rays or beams. We show empirically what combination of factors modulate how an observer experiences this kind of stimulus. We explain how the illusion arises from the interplay of known visual processes, specifically magnocellular and parvocellular dynamics and relate the effects of these ray patterns to other known visual illusions such as illusory contours. Introduction Illusions have played a key role in understanding the principles of perceptual processing (Purkinje, 1825; van Buren & Scholl, 2018), although this notion is not entirely without detractors (Braddick, 2018; Rogers, 2019). One important reason why illusions can be helpful is that they allow us to distinguish the mere sensation of physical object properties from the perceptual experience. This is perhaps clearest in the case of illusory contours. If contours are defined by a sharp change in luminance, it is hard to tell whether the observer “directly” perceives objects in the environment “as they are” or if the percept is constructed in the mind of the observer, because the output of a photometer and perceptual judgments agree (Gibson, 1978; Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1981). Conversely, illusory contours are not defined by changes in luminance, and would be invisible to a photometer, whereas human observers readily perceive them. One example of this is Kanisza’s triangle, which most observers perceive as a bright triangle occluding three black circles - as opposed to the three black pac-man-like shapes are actually defined by luminance (Kanisza, 1955). -

Persistence of Vision Using Arduino

PERSISTENCE OF VISION USING ARDUINO PROJECT REFERENCE NO.: 39S_BE_0215 COLLEGE : MARATHA MANDAL ENGINEERING COLLEGE, BELAGAVI BRANCH : DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING GUIDE : MR. TUSHAR BEDKE STUDENTS : MR. SUSMITH CHARANTIMATH MS. RASHMI R AWARADI MR. SUNEEL LAMANI MR. AMIT KODACHAWAD KEYWORDS: POV (Persistence of Vision), Arduino Nano, DC Motor, Motor speed controller , ATMega , 328 , USB Interfacing, Basic LED’s INTRODUCTION: The core phenomenon on which the entire project is based is the Persistence of vision. Persistence of vision is the phenomenon pertaining to the human eye by which an afterimage is thought to persist for approximately one twenty-fifth of a second on the retina. The way this phenomenon of persistence of vision works is based on the belief that human perception of motion (brain centered) is the result of persistence of vision (eye centered). Any motion that we see around us is the direct implication of persistence of vision phenomenon at work. Persistence of vision is still the accepted term for this phenomenon in the realm of cinema history and theory. Blinky POV [10] is a reprogrammable LED kit that uses persistence of vision to create the illusion of text or a small picture floating in the air. The purpose of this project is to design and create a persistence of vision (POV) display. The display will allow the users to upload an image to be displayed through the wireless communication. A persistence of vision (POV) refers to the phenomenon of the human eye in which an afterimage exists for a brief time (10ms). A POV display exploits this phenomena by spinning in one dimensional row of LED’s through a two dimensional space at such a high frequency that a two dimensional display is visible.