<I>Gloeophyllum Protractum</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Record of Veluticeps Berkeleyi (Basidiomycetes) in the Mediterranean

МИКОЛОГИЯ È ФИТОПАТОЛОГИЯ Том 44 2010 Вып.5 БИОРАЗНООБРАЗИЕ, СИСТЕМАТИКА, ЭКОЛОГИЯ УДК 582.284.99(4—015) ©H.H.Doрan,1 M. Karadelev2 THE FIRST RECORD OF VELUTICEPS BERKELEYI (BASIDIOMYCETES) IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ДОГАНХ.Х., КАРАДЕЛЕВМ. ПЕРВАЯ НАХОДКА VELUTICEPS BERKELEYI (BASIDIOMYCETES) Â СРЕДИЗЕМНОМОРЬЕ The genus Veluticeps (Cooke) Pat. is a striking and distinctive group of wood-decay fun- gi that is associated with brown-rotted wood. Previously, Hjortstam et Tellerнa (1990) ex- panded the concept of Veluticeps to include Columnocystis Pouzar. Nakasone (1990) accep- ted these as synonymous and presents seven species descriptions. Later, Nakasone (2004) worked on a revision of the current status of Veluticeps in the world, and as a result of this work a key to the accepted species of Veluticeps and related taxa was provided. She transfer- red some species such as Veluticeps philippinensis Bres., V. tabacina (Cooke) Burt and V. heimii Malenзon to the genus Pileodon, whereas Campylomyces and only eight species remained in Veluticeps. Currently, the genus Veluticeps includes two groups based on the presence or absence of hyphal pegs. Veluticeps sensu stricto is limited by taxa with hyphal pegs, namely, V. berkeleyi and V. australiensis. Veluticeps sensu lato essentially equivalent to the former genus Columnocystis includes taxa that lack hyphal pegs, namely, Veluticeps abietina (Pers.) Hjortstam et Tellerнa, V. africana (Boidin, Lanq. et Gilles) Hjortstam et Tel- lerнa, V. ambigua (Peck) Hjortstam et Tellerнa, V. fimbriata (Ellis et Everh.) Nakasone, V. fusispora (G. Cunn.) Hjortstam et Ryvarden and V. pimeriensis (Gilbertson) Hjortstam et Tellerнa. Most of the species from the genus have a restricted geographical range and are qu- ite rare except for V. -

Transcriptome Analysis of the Brown Rot Fungus Gloeophyllum Trabeum During Lignocellulose Degradation

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Microbiology Department Faculty Publication Series Microbiology 2020 Transcriptome analysis of the brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum trabeum during lignocellulose degradation Kiwamu Umezawa Mai Niikura Yuka Kojima Barry Goodell Makoto Yoshida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/micro_faculty_pubs PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Transcriptome analysis of the brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum trabeum during lignocellulose degradation 1,2 1 1 3 1 Kiwamu UmezawaID *, Mai Niikura , Yuka Kojima , Barry Goodell , Makoto Yoshida 1 Department of Environmental and Natural Resource Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 2 Department of Applied Biological Chemistry, Kindai University, Nara, Japan, 3 Department of Microbiology, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Brown rot fungi have great potential in biorefinery wood conversion systems because they are the primary wood decomposers in coniferous forests and have an efficient lignocellulose OPEN ACCESS degrading system. Their initial wood degradation mechanism is thought to consist of an oxi- Citation: Umezawa K, Niikura M, Kojima Y, Goodell dative radical-based system that acts sequentially with an enzymatic saccharification sys- B, Yoshida M (2020) Transcriptome analysis of the tem, but the complete molecular mechanism of this system has not yet been elucidated. brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum trabeum during Some studies have shown that wood degradation mechanisms of brown rot fungi have lignocellulose degradation. PLoS ONE 15(12): diversity in their substrate selectivity. Gloeophyllum trabeum, one of the most studied brown e0243984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0243984 rot species, has broad substrate selectivity and even can degrade some grasses. -

Fruiting Body Form, Not Nutritional Mode, Is the Major Driver of Diversification in Mushroom-Forming Fungi

Fruiting body form, not nutritional mode, is the major driver of diversification in mushroom-forming fungi Marisol Sánchez-Garcíaa,b, Martin Rybergc, Faheema Kalsoom Khanc, Torda Vargad, László G. Nagyd, and David S. Hibbetta,1 aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610; bUppsala Biocentre, Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-75005 Uppsala, Sweden; cDepartment of Organismal Biology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden; and dSynthetic and Systems Biology Unit, Institute of Biochemistry, Biological Research Center, 6726 Szeged, Hungary Edited by David M. Hillis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved October 16, 2020 (received for review December 22, 2019) With ∼36,000 described species, Agaricomycetes are among the and the evolution of enclosed spore-bearing structures. It has most successful groups of Fungi. Agaricomycetes display great di- been hypothesized that the loss of ballistospory is irreversible versity in fruiting body forms and nutritional modes. Most have because it involves a complex suite of anatomical features gen- pileate-stipitate fruiting bodies (with a cap and stalk), but the erating a “surface tension catapult” (8, 11). The effect of gas- group also contains crust-like resupinate fungi, polypores, coral teroid fruiting body forms on diversification rates has been fungi, and gasteroid forms (e.g., puffballs and stinkhorns). Some assessed in Sclerodermatineae, Boletales, Phallomycetidae, and Agaricomycetes enter into ectomycorrhizal symbioses with plants, Lycoperdaceae, where it was found that lineages with this type of while others are decayers (saprotrophs) or pathogens. We constructed morphology have diversified at higher rates than nongasteroid a megaphylogeny of 8,400 species and used it to test the following lineages (12). -

Polypore Diversity in North America with an Annotated Checklist

Mycol Progress (2016) 15:771–790 DOI 10.1007/s11557-016-1207-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Polypore diversity in North America with an annotated checklist Li-Wei Zhou1 & Karen K. Nakasone2 & Harold H. Burdsall Jr.2 & James Ginns3 & Josef Vlasák4 & Otto Miettinen5 & Viacheslav Spirin5 & Tuomo Niemelä 5 & Hai-Sheng Yuan1 & Shuang-Hui He6 & Bao-Kai Cui6 & Jia-Hui Xing6 & Yu-Cheng Dai6 Received: 20 May 2016 /Accepted: 9 June 2016 /Published online: 30 June 2016 # German Mycological Society and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 Abstract Profound changes to the taxonomy and classifica- 11 orders, while six other species from three genera have tion of polypores have occurred since the advent of molecular uncertain taxonomic position at the order level. Three orders, phylogenetics in the 1990s. The last major monograph of viz. Polyporales, Hymenochaetales and Russulales, accom- North American polypores was published by Gilbertson and modate most of polypore species (93.7 %) and genera Ryvarden in 1986–1987. In the intervening 30 years, new (88.8 %). We hope that this updated checklist will inspire species, new combinations, and new records of polypores future studies in the polypore mycota of North America and were reported from North America. As a result, an updated contribute to the diversity and systematics of polypores checklist of North American polypores is needed to reflect the worldwide. polypore diversity in there. We recognize 492 species of polypores from 146 genera in North America. Of these, 232 Keywords Basidiomycota . Phylogeny . Taxonomy . species are unchanged from Gilbertson and Ryvarden’smono- Wood-decaying fungus graph, and 175 species required name or authority changes. -

Polypore Fungi As a Flagship Group to Indicate Changes in Biodiversity – a Test Case from Estonia Kadri Runnel1* , Otto Miettinen2 and Asko Lõhmus1

Runnel et al. IMA Fungus (2021) 12:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-020-00050-y IMA Fungus RESEARCH Open Access Polypore fungi as a flagship group to indicate changes in biodiversity – a test case from Estonia Kadri Runnel1* , Otto Miettinen2 and Asko Lõhmus1 Abstract Polyporous fungi, a morphologically delineated group of Agaricomycetes (Basidiomycota), are considered well studied in Europe and used as model group in ecological studies and for conservation. Such broad interest, including widespread sampling and DNA based taxonomic revisions, is rapidly transforming our basic understanding of polypore diversity and natural history. We integrated over 40,000 historical and modern records of polypores in Estonia (hemiboreal Europe), revealing 227 species, and including Polyporus submelanopus and P. ulleungus as novelties for Europe. Taxonomic and conservation problems were distinguished for 13 unresolved subgroups. The estimated species pool exceeds 260 species in Estonia, including at least 20 likely undescribed species (here documented as distinct DNA lineages related to accepted species in, e.g., Ceriporia, Coltricia, Physisporinus, Sidera and Sistotrema). Four broad ecological patterns are described: (1) polypore assemblage organization in natural forests follows major soil and tree-composition gradients; (2) landscape-scale polypore diversity homogenizes due to draining of peatland forests and reduction of nemoral broad-leaved trees (wooded meadows and parks buffer the latter); (3) species having parasitic or brown-rot life-strategies are more substrate- specific; and (4) assemblage differences among woody substrates reveal habitat management priorities. Our update reveals extensive overlap of polypore biota throughout North Europe. We estimate that in Estonia, the biota experienced ca. 3–5% species turnover during the twentieth century, but exotic species remain rare and have not attained key functions in natural ecosystems. -

First Record of Neolentinus Lepideus F. Ceratoides (Gloeophyllales, Basidiomycota) in Novosibirsk Region

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 7(3): 187–192 (2017) ISSN 2229-2225 www.creamjournal.org Article Doi 10.5943/cream/7/3/5 Copyright © Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences First record of Neolentinus lepideus f. ceratoides (Gloeophyllales, Basidiomycota) in Novosibirsk Region Vlasenko VA1, Vlasenko AV1 and Zmitrovich IV2 1Central Siberian Botanical Garden, Siberian branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Zolotodolinskaya, 101, Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia. 2 Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov, 2, St. Petersburg, 197376, Russia. Vlasenko VA, Vlasenko AV, Zmitrovich IV 2017 – First record of Neolentinus lepideus f. ceratoides (Gloeophyllales, Basidiomycota) in Novosibirsk Region. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 7(3), 187–192, Doi 10.5943/cream/7/3/5 Abstract Deviant form of wood-decaying basidiomycete Neolentinus lepideus was found in western Siberia, the rare sterile form N. lepideus f. ceratoides was found in the Novosibirsk Region. The description and an illustration of taxon is provided. The sterile form does not produce a hymenophore. It is formed under conditions of darkness on wood constructions in caves, grottos, mines, cellars, basements and under the floor. Sterile bodies of the fungus of horn appearance have a clavarioid morphotype. They are coral-like branched, with elongated rounded sprouts extending from the common trunk, which under normal conditions would have given a stipe. The caps with lamellar hymenophore, which would appear on normal fruiting bodies, are completely absent. Monstrose forms in Neolentinus species represents morphological modifications of fruiting bodies, associated with disturbance of normal morphogenesis under dark or shady conditions. -

Diversität Und Ökologie Holzbewohnender Pilze in Khonin Nuga, Westkhentey, Mongolei

Diversität und Ökologie holzbewohnender Pilze in Khonin Nuga, Westkhentey, Mongolei Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Georg-August-Universität zu Göttingen vorgelegt von Renchin Sunjidmaa aus Zavkhan, Mongolei Göttingen 2009 D 7 Referent: Prof. Dr. M. Mühlenberg Korreferent: PD Dr. M. Hauck (Professurvertretung) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 29.06.2009 Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................................................................................. iv Transliteration kyrillischer Buchstaben ..................................................................................... v 1. Einführung.............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Die Rolle holzbewohnender Pilze in Ökosystemen ........................................................ 1 1.2 Studien über holzbewohnende Pilze................................................................................. 2 1.3. Ziel der Dissertationsarbeit ............................................................................................. 4 2. Untersuchungsgebiet .............................................................................................................. 5 2.1. Die Mongolei................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Khonin Nuga .................................................................................................................. -

Research Article Brown Rot-Type Fungal Decomposition of Sorghum Bagasse: Variable Success and Mechanistic Implications

Hindawi International Journal of Microbiology Volume 2018, Article ID 4961726, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4961726 Research Article Brown Rot-Type Fungal Decomposition of Sorghum Bagasse: Variable Success and Mechanistic Implications Gerald N. Presley ,1 Bongani K. Ndimba,2,3 and Jonathan S. Schilling 1,4 1 Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering, University of Minnesota, 2004 Folwell Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 2Agricultural Research Council of South Africa (ARC-Infruitec/Nietvoorbij), Private Bag X5026, Stellenbosch 7599, South Africa 3Department of Biotechnology, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, South Africa 4Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of Minnesota, 1500 Gortner Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Jonathan S. Schilling; [email protected] Received 17 October 2017; Accepted 27 February 2018; Published 3 April 2018 Academic Editor: Giuseppe Comi Copyright © 2018 Gerald N. Presley et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Sweet sorghum is a promising crop for a warming, drying African climate, and basic information is lacking on conversion pathways for its lignocellulosic residues (bagasse). Brown rot wood-decomposer fungi use carbohydrate-selective pathways that, when assessed on sorghum, a grass substrate, can yield information relevant to both plant biomass conversion and fungal biology. In testing sorghum decomposition by brown rot fungi (Gloeophyllum trabeum, Serpula lacrymans), we found that G. trabeum readily degraded sorghum, removing xylan prior to removing glucan. Serpula lacrymans, conversely, caused little decomposition. -

Unusual Monstrose Form of Neolentinus Cyathiformis (Gloeophyllaceae, Basidiomycota) from the Novosibirsk Region (Russia) Vyacheslav A

Botanica Pacifica. A journal of plant science and conservation. 2019. 8(1): 81–84 DOI: 10.17581/bp.2019.08102 Unusual monstrose form of Neolentinus cyathiformis (Gloeophyllaceae, Basidiomycota) from the Novosibirsk Region (Russia) Vyacheslav A. Vlasenko1*, Ivan V. Zmitrovich2 & Anastasia V. Vlasenko1 Vyacheslav A. Vlasenko1* ABSTRACT e-mail: [email protected] A deviant form of wood-decaying basidiomycete Neolentinus cyathiformis found in Ivan V. Zmitrovich2 the Novosibirsk Region is described as new to science. In this report, we provide e-mail: [email protected] the description and illustration of new taxon. Previously, monstrose forms have Anastasia V. Vlasenko1 never been observed for this species. Morphological abnormalities leading to a e-mail: [email protected] total change in the habitus of the fruit body are more characteristic of another rep- resentative of the genus Neolentinus, N. lepideus. The described form is characte rized by the presence of producing spores hymenial surface on the upper side of the cap 1 Central Siberian Botanical Garden SB of the fruit body on the outgrowths, in which the pits resembling the volcano’s RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia vents are located. 2 V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute RAS, Keywords: Lentinoid fungi, morphological variability, monstrose forms, Neolentinus St. Petersburg, Russia РЕЗЮМЕ Власенко В.А., Змитрович И.В., Власенко А.В. Необычная монст роз * corresponding author ная форма Neolentinus cyathiformis (Gloeophyllaceae) из Новосибирской области. Описана новая для науки монстрозная форма дереворазрушаю- Manuscript received: 07.08.2018 щего базидиомицета Neolentinus cyathiformis, обнаруженная в Новосибирской Review completed: 15.01.2019 области. Приводится описание и иллюстрация таксона. Ранее для данного Accepted for publication: 17.01.2019 вида монстрозные формы не отмечались. -

Polyporaceae of Iowa: a Taxonomic, Numerical and Electrophoretic Study Robert John Pinette Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 Polyporaceae of Iowa: a taxonomic, numerical and electrophoretic study Robert John Pinette Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Pinette, Robert John, "Polyporaceae of Iowa: a taxonomic, numerical and electrophoretic study " (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 8954. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/8954 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

A Database of the Global Distribution of Alien Macrofungi

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e51459 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e51459 Data Paper A database of the global distribution of alien macrofungi Miguel Monteiro‡,§,|, Luís Reino ‡,§, Anna Schertler¶¶, Franz Essl , Rui Figueira‡,§,#, Maria Teresa Ferreira|, César Capinha ¤ ‡ CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal § CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal | Centro de Estudos Florestais, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal ¶ Division of Conservation Biology, Vegetation Ecology and Landscape Ecology, Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria # LEAF-Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal ¤ Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território - IGOT, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal Corresponding author: César Capinha ([email protected]) Academic editor: Dmitry Schigel Received: 25 Feb 2020 | Accepted: 16 Mar 2020 | Published: 01 Apr 2020 Citation: Monteiro M, Reino L, Schertler A, Essl F, Figueira R, Ferreira MT, Capinha C (2020) A database of the global distribution of alien macrofungi. Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e51459. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e51459 Abstract Background Human activities are allowing the ever-increasing dispersal of taxa to beyond their native ranges. Understanding the patterns and implications of these distributional changes requires comprehensive information on the geography of introduced species. Current knowledge about the alien distribution of macrofungi is limited taxonomically and temporally, which severely hinders the study of human-mediated distribution changes for this taxonomic group. -

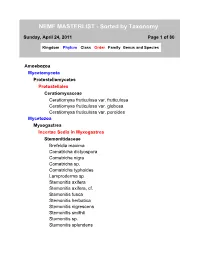

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, April 24, 2011 Page 1 of 80 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus and Species Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. globosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha dictyospora Comatricha nigra Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Lamproderma sp. Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis axifera, cf. Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis herbatica Stemonitis nigrescens Stemonitis smithii Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Capnodium tiliae Diaporthales Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsaria peckii Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces muricatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera alni Microsphaera alphitoides Microsphaera penicillata Uncinula sp. Halosphaeriales Halosphaeriaceae Cerioporiopsis pannocintus Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Hysterium angustatum Micothyriales Microthyriaceae Microthyrium sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Ostropales Graphidaceae Graphis scripta Stictidaceae Cryptodiscus sp. 1 Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Peltigeraceae Peltigera canina Peltigera evansiana Peltigera horizontalis Peltigera membranacea Peltigera praetextala Pertusariales Icmadophilaceae Dibaeis baeomyces Pezizales