The Consolation of the Firstborn in Genesis: a Lesson for Christian Mission JAMES C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D

Names 39.2 (June 1991) Most Common Jewish First Names in Israel Edwin D. Lawson1 Abstract Samples of men's and women's names drawn from English language editions of Israeli telephone directories identify the most common names in current usage. These names, categorized into Biblical, Traditional, Modern Hebrew, and Non-Hebrew groups, indicate that for both men and women over 90 percent come from Hebrew, with the Bible accounting for over 70 percent of the male names and about 40 percent of the female. Pronunciation, meaning, and Bible citation (where appropriate) are given for each name. ***** The State of Israel represents a tremendous opportunity for names research. Immigrants from traditions and cultures as diverse as those of Yemen, India, Russia, and the United States have added their onomastic contributions to the already existing Jewish culture. The observer accustomed to familiar first names of American Jews is initially puzzled by the first names of Israelis. Some of them appear to be biblical, albeit strangely spelled; others appear very different. What are these names and what are their origins? Benzion Kaganoffhas given part of the answer (1-85). He describes the evolution of modern Jewish naming practices and has dealt specifi- cally with the change of names of Israeli immigrants. Many, perhaps most, of the Jews who went to Israel changed or modified either personal or family name or both as part of the formation of a new identity. However, not all immigrants changed their names. Names such as David, Michael, or Jacob required no change since they were already Hebrew names. -

Tamar: Conscious Choices and Choosing One's Own Destiny

Tamar: Conscious Choices and Choosing One’s Own Destiny Parashat Vayeishev (Genesis 38: 1 – 30) Do you make conscious choices? One of our Torah heroines surely did. Tamar made a conscious choice following the deaths of her husband, Judah’s son Er, Judah’s next son Onan, and Judah’s wife Hirah. Tamar became a childless widow and it seemed as though Judah had no plan to allow his youngest son Shelah to marry Tamar, as biblical law mandated. Judah claimed that Shelah was too young and he could not risk losing another son. However, our heroine Tamar needed a child in order to claim a true stake in the household of Judah. So, she tricked her father-in-law Judah into sleeping with her during his bereavement. Posing as a harlot, Judah solicited Tamar’s services, willingly giving Tamar his signet seal, his cord and his staff, all of which clearly identified him when she would later proclaim Judah’s paternity for her twin sons Perez and Zerah. Not for love or for lust, but rather for a legacy into the future, Tamar made a conscious choice. She took initiative. She changed destiny. And, ironically, Judah admitted, “She is more in the right than I!” (Genesis 38:26) Judah had refused the rights of levirate marriage to Tamar. It all returns to making choices. Each woman on our sisterhood roster has made a conscious choice to join sisterhood. We are grateful to the women who choose to join sisterhood and our congregation, for choosing the path of leadership, and for sharing mitzvah time. -

PART TWO Critical Studies –

PART TWO Critical Studies – David T. Runia - 9789004216853 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/2021 02:06:05PM via free access David T. Runia - 9789004216853 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/2021 02:06:05PM via free access . Monique Alexandre, ‘Du grec au latin: Les titres des œuvres de Philon d’Alexandrie,’ in S. Deléani and J.-C. Fredouille (edd.), Titres et articulations du texte dans les œuvres antiques: actes du Colloque International de Chantilly, – décembre , Collection des Études Augustiniennes (Paris ) –. This impressive piece of historical research is divided into three main parts. In a preliminary section Alexandre first gives a brief survey of the study of the transmission of the corpus Philonicum in modern scholarship and announces the theme of her article, namely to present some reflections on the Latin titles now in general use in Philonic scholarship. In the first part of the article she shows how the replacement of Greek titles by Latin ones is part of the humanist tradition, and is illustrated by the history of Philonic editions from Turnebus to Arnaldez– Pouilloux–Mondésert. She then goes on in the second part to examine the Latin tradition of Philo’s reception in antiquity (Jerome, Rufinus, the Old Latin translation) in order to see whether the titles transmitted by it were influential in determining the Latin titles used in the editions. This appears to have hardly been the case. In the third part the titles now in use are analysed. Most of them were invented by the humanists of the Renaissance and the succeeding period; only a few are the work of philologists of the th century. -

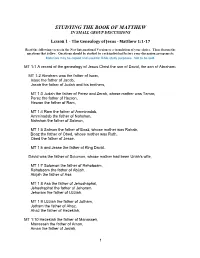

Studying the Book of Matthew in Small Group Discussions

STUDYING THE BOOK OF MATTHEW IN SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS Lesson 1 - The Genealogy of Jesus - Matthew 1:1-17 Read the following verses in the New International Version or a translation of your choice. Then discuss the questions that follow. Questions should be studied by each individual before your discussion group meets. Materials may be copied and used for Bible study purposes. Not to be sold. MT 1:1 A record of the genealogy of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham: MT 1:2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, Isaac the father of Jacob, Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, MT 1:3 Judah the father of Perez and Zerah, whose mother was Tamar, Perez the father of Hezron, Hezron the father of Ram, MT 1:4 Ram the father of Amminadab, Amminadab the father of Nahshon, Nahshon the father of Salmon, MT 1:5 Salmon the father of Boaz, whose mother was Rahab, Boaz the father of Obed, whose mother was Ruth, Obed the father of Jesse, MT 1:6 and Jesse the father of King David. David was the father of Solomon, whose mother had been Uriah's wife, MT 1:7 Solomon the father of Rehoboam, Rehoboam the father of Abijah, Abijah the father of Asa, MT 1:8 Asa the father of Jehoshaphat, Jehoshaphat the father of Jehoram, Jehoram the father of Uzziah, MT 1:9 Uzziah the father of Jotham, Jotham the father of Ahaz, Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, MT 1:10 Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, Manasseh the father of Amon, Amon the father of Josiah, 1 MT 1:11 and Josiah the father of Jeconiah* and his brothers at the time of the exile to Babylon. -

Notes on Ruth 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Ruth 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE This book received its title in honor of the heroine of the story. One writer argued that "Naomi" is the main character in the plot, "Boaz" is the main character in the dialogue, and "Obed" is the main character in the purpose of the book.1 The name "Ruth" may mean "friendship," "comfort," or "refreshment." It appears to have been Moabite and not Hebrew, originally, though its etymological derivation is uncertain.2 Another writer suggested it may derive from the Hebrew root rwh, meaning "to soak, irrigate, refresh."3 After Ruth entered Israel, and especially after the Book of Ruth circulated, the name became popular among the Jews, and later among Christians. The same title appears over the book in its Hebrew (Masoretic), Greek (Septuagint), Latin (Vulgate), and modern language versions. DATE AND WRITER It is safe to assume that the Book of Ruth was put in its final form after David became king in Hebron, in 1011 B.C., since he is recognized as a very important figure in the genealogy (4:17, 22). How much later is hard to determine. The Babylonian Talmud attributed authorship of the book to Samuel.4 This statement reflects ancient Jewish tradition. If Samuel, or someone who lived about the same time as Samuel, wrote the book, the final genealogy must have been added much later—perhaps during the reign of David or Solomon. Modern critical scholars tend to prefer a much later date, on the basis of their theories concerning the date of the writing 1Daniel I. -

Scrolls of Love Ruth and the Song of Songs Scrolls of Love

Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg Scrolls of Love ruth and the song of songs Scrolls of Love ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE i ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE ii Scrolls of Love reading ruth and the song of songs Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York / 2006 ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2006 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scrolls of love : reading Ruth and the Song of songs / edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2526-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2526-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Ruth—Criticism interpretation, etc. 2. Bible. O.T. Song of Solomon—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Hawkins, Peter S. II. Stahlberg, Lesleigh Cushing. BS1315.52.S37 2006 222Ј.3506—dc22 2006029474 Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 First edition ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iv For John Clayton (1943–2003), mentor and friend ................ -

Introduction: Major Ethics/Leadership Issue: CAPTIVITY

ISHMAEL Daniel Quinn EDLD 555: Group 2 Introduction: The book Ishmael by Daniel Quinn explores the relationship between an ageing guerilla and a man seeking to change the world. Through a form of nonverbal communication, they discussed God, man, and how both relate to the destruction of the natural world. Daniel Quinn, winner of the Turner Tomorrow Fellowship Award, wrote this book to explore his views on the environment and what man can do to solve this issue and other major global issues facing the world today. Major Ethics/Leadership Issue: CAPTIVITY DESCRIPTION: Just as animals are captive in a zoo, humans are also held captive by a human-centric system that we’ve created—we are “captives of a civilizational system that more or less compels you to go on destroying the world in order to live” (Quinn, 1992, p.25). POINT OF VIEW OF THE AUTHOR: Humans do not necessarily see their existence as a form of captivity. By seeing the world as made for man, humans have divided themselves into groups and do conquer whatever they need, to guarantee their own survival. In the process of disregarding laws of nature and living by the laws of man, humans are creating a system that is destroying the earth at the expense of their own “survival”. In essence, the daily actions of humans facilitate their captivity. CONTRASTING POINT OF VIEW TO THE AUTHOR’S: Man is the reason that the earth was created. Man’s purpose is to create a paradise on earth for all people. Man has freedom to do whatever s/he needs to do in order to follow the path s/he thinks will lead to peace, prosperity and freedom for all. -

God's Rejection of Cain Outside the Garden of Eden (Genesis 4:1-16)

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Sacred Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship Spring 5-18-2018 Falling Far from the Tree? God's Rejection of Cain outside the Garden of Eden (Genesis 4:1-16) Mark Remington Squire Concordia Seminary - St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/stm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Squire, Mark Remington, "Falling Far from the Tree? God's Rejection of Cain outside the Garden of Eden (Genesis 4:1-16)" (2018). Master of Sacred Theology Thesis. 395. https://scholar.csl.edu/stm/395 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Sacred Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALLING FAR FROM THE TREE? GOD’S REJECTION OF CAIN OUTSIDE THE GARDEN OF EDEN (GENESIS 4:1–16) A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Exegetical Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Sacred Theology By Mark Remington Squire April 2018 Approved by Dr. David L. Adams Advisor Rev. Thomas J. Egger Reader Dr. Joel C. Elowsky Reader © 2018 by Mark Remington Squire. All rights reserved. ii CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... v ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... -

The Animal Teacher in Daniel Quinn's Ishmael

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos 22 (2018), Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, 305-325 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2018.i22.13 THE ANIMAL TEACHER IN DANIEL QUINN’S ISHMAEL DIANA VILLANUEVA ROMERO Universidad de Extremadura; GIECO, I. Franklin-UAH; CILEM-UEx Received 31 July 2018 Accepted 9 February 2019 KEYWORDS Quinn; Ishmael; animal literature; captivity; environmental literature; primates; fable; Holocaust. PALABRAS CLAVES Quinn; Ishmael; literatura de animales; cautividad; literatura ambiental; primates; fábula; Holocausto. ABSTRACT This article aims at offering an analysis of the animal protagonist of Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) by American author Daniel Quinn as well as his environmental lesson. This book tells the story of the relationship between a human and an animal teacher, the telepathic gorilla Ishmael. Throughout their conversations some of the reasons behind the environmental crisis are discussed and the need for a shift in the Western paradigm is defended. Special attention is given throughout this artice to the gorilla’s acquisition of personhood, his Socratic method, his thorough lesson on animal and human captivity, and the timeless quality of a fable that continues resonating with many of the global attempts towards a more sustainable world. RESUMEN Este artículo pretende ofrecer un análisis del animal protagonista en Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) del autor norteamericano Daniel Quinn, así como de su lección ambiental. Este libro cuenta la historia de la relación entre un humano y su maestro, el gorila telepático Ishmael. A través de sus conversaciones se discuten algunas de las razones de la crisis ambiental y se defiende la necesidad de un cambio en el paradigma occidental. -

THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMAGINATIONS of MOBY-DICK: TECHNOLOGY and VULNERABILITY in HUMAN/MORE- THAN-HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS Jensen A

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2019 THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMAGINATIONS OF MOBY-DICK: TECHNOLOGY AND VULNERABILITY IN HUMAN/MORE- THAN-HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS Jensen A. Lillquist University of Montana, Missoula Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Lillquist, Jensen A., "THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMAGINATIONS OF MOBY-DICK: TECHNOLOGY AND VULNERABILITY IN HUMAN/MORE-THAN-HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS" (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11320. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11320 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMAGINATIONS OF MOBY-DICK: TECHNOLOGY AND VULNERABILITY IN HUMAN/MORE-THAN-HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS By JENSEN ARTHUR LILLQUIST Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2017 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in English Literature, Ecocriticism The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2019 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Louise Economides, Co-Chair Department of English Dr. Katie Kane, Co-Chair Department of English Dr. Christopher Preston Department of Philosophy i Lillquist, Jensen, M.A., May 2019 English Literature The Environmental Imaginations of Moby-Dick: Technology and Vulnerability in Human/More- than-Human Relationships Co-Chairperson: Dr. -

The Gospel According to Luke Luke 3:15-22 ESV February 4-10, 2019

The Gospel According to Luke Luke 3:15-22 ESV February 4-10, 2019 Luke 3:23-38 “Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph, the son of Heli, the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, the son of Melchi, the son of Jannai, the son of Joseph, the son of Mattathias, the son of Amos, the son of Nahum, the son of Esli, the son of Naggai, the son of Maath, the son of Mattathias, the son of Semein, the son of Josech, the son of Joda, the son of Joanan, the son of Rhesa, the son of Zerubbabel, the son of Shealtiel, the son of Neri, the son of Melchi, the son of Addi, the son of Cosam, the son of Elmadam, the son of Er, the son of Joshua, the son of Eliezer, the son of Jorim, the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, the son of Simeon, the son of Judah, the son of Joseph, the son of Jonam, the son of Eliakim, the son of Melea, the son of Menna, the son of Mattatha, the son of Nathan, the son of David, the son of Jesse, the son of Obed, the son of Boaz, the son of Sala, the son of Nahshon, the son of Amminadab, the son of Admin, the son of Arni, the son of Hezron, the son of Perez, the son of Judah, the son of Jacob, the son of Isaac, the son of Abraham, the son of Terah, the son of Nahor, the son of Serug, the son of Reu, the son of Peleg, the son of Eber, the son of Shelah, the son of Cainan, the son of Arphaxad, the son of Shem, the son of Noah, the son of Lamech, the son of Methuselah, the son of Enoch, the son of Jared, the son of Mahalaleel, the son of Cainan, the son of Enos, the son of Seth, the son of Adam, the son of God.” Luke 3:23-38 ESV This passage can be described as “Biblical flyover country” - seemingly not very exciting but vitally important if we are willing to take the time to explore. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.