Short Communication Matriphagy in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Short-Range Endemic Invertebrate Fauna of the Ravensthorpe Range

THE SHORT-RANGE ENDEMIC INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF THE RAVENSTHORPE RANGE MARK S. HARVEY MEI CHEN LENG Department of Terrestrial Zoology Western Australian Museum June 2008 2 Executive Summary An intensive survey of short-range endemic invertebrates in the Ravensthorpe Range at 79 sites revealed a small but significant fauna of myriapods and arachnids. Four species of short-range endemic invertebrates were found: • The millipede Antichiropus sp. R • The millipede Atelomastix sp. C • The millipede Atelomastix sp. P • The pseudoscorpion Amblyolpium sp. “WA1” Atelomastix sp. C is the only species found to be endemic to the Ravensthorpe Range and was found at 14 sites. Antichiropus sp. R, Atelomastix sp. P and Amblyolpium sp. “WA1” are also found at nearby locations. Sites of high importance include: site 40 with 7 species; sites 7 and 48 each with 5 species; and sites 18 and 44 each with 4 species. WA Museum - Ravensthorpe Range Survey 3 Introduction Australia contains a multitude of terrestrial invertebrate fauna species, with many yet to be discovered and described. Arthropods alone were recently estimated to consist of approximately more than 250,000 species (Yeates et al. 2004). The majority of these belong to the arthropod classes Insecta and Arachnida, and although many have relatively wide distributions across the landscape, some are highly restricted in range with special ecological requirements. These taxa, termed short-range endemics (Harvey 2002b), are taxa categorised as having poor dispersal abilities and/or requiring very specific habitats, usually with naturally small distributional ranges of less than 10,000 km2 and the following ecological and life-history traits: • poor powers of dispersal; • confinement to discontinuous habitats; • usually highly seasonal, only active during cooler, wetter periods; and • low levels of fecundity. -

The Genetic Basis of Natural Variation in the Response to Adult

THE GENETIC BASIS OF NATURAL VARIATION IN THE RESPONSE TO ADULT STARVATION IN CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS by HEATHER M. ARCHER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Biology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Heather M. Archer Title: The Genetic Basis of Natural Variation in the Response to Adult Starvation in Caenorhabditis elegans This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Biology by: John Conery Chairperson Patrick Phillips Advisor John Postlethwait Core Member William Cresko Core Member Michael Harms Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019 ii © 2019 Heather M. Archer iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Heather M. Archer Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology June 2019 Title: Assessment of Natural Variation in the Response to Adult Starvation in Caenorhabditis elegans Caenorhabditis elegans typically feeds on rotting fruit and plant material in a fluctuating natural habitat, a boom-and-bust lifestyle. Moreover, stage specific developmental responses to low food concentration suggest that starvation-like conditions are a regular occurrence. In order to assess variation in the C. elegans starvation response under precisely controlled conditions and simultaneously phenotype a large number of individuals with high precision, we have developed a microfluidic device that, when combined with image scanning technology, allows for high-throughput assessment at a temporal resolution not previously feasible and applied this to a large mapping panel of fully sequenced intercross lines. -

Distribution of Cave-Dwelling Pseudoscorpions (Arachnida) in Brazil

2019. Journal of Arachnology 47:110–123 Distribution of cave-dwelling pseudoscorpions (Arachnida) in Brazil Diego Monteiro Von Schimonsky1,2 and Maria Elina Bichuette1: 1Laborato´rio de Estudos Subterraˆneos – Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva – Universidade Federal de Sa˜o Carlos, Rodovia Washington Lu´ıs, km 235, Caixa Postal 676, CEP 13565-905, Sa˜o Carlos, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil; 2Programa de Po´s-Graduac¸a˜o em Biologia Comparada, Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Cieˆncias e Letras de Ribeira˜o Preto – Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Av. Bandeirantes, 3900, CEP 14040-901, Bairro Monte Alegre, Ribeira˜o Preto, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Pseudoscorpions are among the most diverse of the smaller arachnid orders, but there is relatively little information about the distribution of these tiny animals, especially in Neotropical caves. Here, we map the distribution of the pseudoscorpions in Brazilian caves and record 12 families and 22 genera based on collections analyzed over several years, totaling 239 caves from 13 states in Brazil. Among them, two families (Atemnidae and Geogarypidae) with three genera (Brazilatemnus Muchmore, 1975, Paratemnoides Harvey, 1991 and Geogarypus Chamberlin, 1930) are recorded for the first time in cave habitats as, well as seven other genera previously unknown for Brazilian caves (Olpiolum Beier, 1931, Pachyolpium Beier 1931, Tyrannochthonius Chamberlin, 1929, Lagynochthonius Beier, 1951, Neocheiridium Beier 1932, Ideoblothrus Balzan, 1892 and Heterolophus To¨mo¨sva´ry, 1884). These genera are from families already recorded in this habitat, which have their distributional ranges expanded for all other previously recorded genera. Additionally, we summarize records of Pseudoscorpiones based on previously published literature and our data for 314 caves. -

Pseudoscorpiones: Atemnidae) from China

JoTT SHORT COMMUNI C ATION 4(11): 3059–3066 Notes on two species of the genus Atemnus Canestrini (Pseudoscorpiones: Atemnidae) from China Jun-fang Hu 1 & Feng Zhang 2 1,2 College of Life Sciences, Hebei University, Baoding, Hebei 071002 China Email: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: Two pseudoscorpion species of the genus Atemnus region, A. strinatii Beier, 1977 from the Philippines, Canestrini, 1884 are reported from China: A. limuensis sp. nov. from the Ormosia tree bark in a humid tropical forest and A. A. syriacus (Beier, 1955) from Europe and the Middle politus Simon, 1878 from leaf litter in a temperate deciduous East, and A. politus (Simon, 1878) widely distributed forest. A key to all known species of this genus is provided. from Europe and northern Africa to Asia, including Keywords: Atemnus, China, new species, pseudoscorpions, China (Harvey 2011). taxonomy. With support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the authors began to collect and The pseudoscorpion family Atemnidae Kishida, study Chinese pseudoscorpions in 2007. Two Atemnus 1929 (see Judson 2010) is divided into two subfamilies species have been found in our collection, including and 19 genera, with four species and four genera a new Atemnus species from Hainan, which differs from China (Atemnus Canestrini, 1884, Anatemnus morphologically from other Atemnus species in China Beier, 1932 and Paratemnoides Harvey, 1991 of the and A. politus from Shanxi Province. In this paper, subfamily Atemninae Kishida, 1929 and Diplotemnus we describe the new species and provide a detailed Chamberlin, 1933 of the subfamily Miratemninae description of A. -

Benefits of Cooperation with Genetic Kin in a Subsocial Spider

Benefits of cooperation with genetic kin in a subsocial spider J. M. Schneider*† and T. Bilde†‡§ *Biozentrum Grindel, University of Hamburg, Martin-Luther-King Platz 3, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; ‡Ecology and Genetics, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Aarhus, Ny Munkegade Building 1540, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark; and §Animal Ecology, Department of Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary Biology Centre, University of Uppsala, Norbyva¨gen 18d, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden Edited by Bert Ho¨lldobler, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, and approved May 29, 2008 (received for review May 2, 2008) Interaction within groups exploiting a common resource may be tional systems may be especially illuminating (10), because once prone to cheating by selfish actions that result in disadvantages for established, cooperation may underlie novel selection regimes all members of the group, including the selfish individuals. Kin that override initial selection pressures (5, 11). Here we inves- selection is one mechanism by which such dilemmas can be re- tigate whether kin selection reduces the negative effects of solved This is because selfish acts toward relatives include the cost competition or selfish actions in a communally hunting spider of lowering indirect fitness benefits that could otherwise be described as a transitory species toward permanent sociality. achieved through the propagation of shared genes. Kin selection Communally feeding spiders are ideal to investigate costs and theory has been proved to be of general importance for the origin benefits of cooperation because of their feeding mode. Subsocial of cooperative behaviors, but other driving forces, such as direct and social spiders are known to hunt cooperatively; not only do fitness benefits, can also promote helping behavior in many they build and share a common capture web, but they also share cooperatively breeding taxa. -

Benefits and Costs of Parental Care (Ed NJR)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital.CSIC Chapter 3: Benefits and costs of parental care (Ed NJR) Carlos Alonso‐Alvarez and Alberto Velando 3.1. Introduction In order to explain the huge variation in parental behaviour evolutionary biologists have traditionally used a cost‐benefit approach, which enables them to analyse behavioural traits in terms of the positive and negative effects on the transmission of parental genes to the next generation. Empirical evidence supports the presence of a number of different trade‐offs between the costs and benefits associated with parental care (Stearns 1992; Harshman and Zera 2007), although the mechanisms they are governed by are still the object of debate. In fact, Clutton‐Brock’s (1991) seminal book did not address the mechanistic bases of parental care and most work in this field has been conducted over the last 20 years. Research on mechanisms has revealed that to understand parental care behaviour we need to move away from traditional models based exclusively on currencies of energy/time. Nevertheless, despite repeated claims, the integration of proximate mechanisms into ultimate explanations is currently far from successful (e.g. Barnes and Partridge 2003; McNamara and Houston 2009). In this chapter, nonetheless, we aim to describe the most relevant advances in this field. In this chapter, we employ Clutton‐Brock’s (1991) definitions of the costs and benefits of parental care. Costs imply a reduction in the number of offspring other than those that are currently receiving care (i.e. parental investment, Trivers 1972), whereas benefits are increased fitness in the offspring currently being cared for. -

Climatic Variables Are Strong Predictors of Allonursing and Communal Nesting in Primates

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College 2-1-2019 Climatic variables are strong predictors of allonursing and communal nesting in primates Alexandra Louppova CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Climatic variables are strong predictors of allonursing and communal nesting in primates by Alexandra Louppova Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anthropology, Hunter College The City University of New York 2018 Thesis Sponsor: Andrea Baden December 15, 2018 Date Signature of First Reader Dr. Andrea Baden December 15, 2018 Date Signature of Second Reader Dr. Jason Kamilar Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................ -

A New Species of the Genus Anatemnus (Pseudoscorpiones, Atemnidae) from China

International Scholarly Research Network ISRN Zoology Volume 2012, Article ID 164753, 3 pages doi:10.5402/2012/164753 Research Article A New Species of the Genus Anatemnus (Pseudoscorpiones, Atemnidae) from China Jun-Fang Hu and Feng Zhang College of Life Sciences, Hebei University, Hebei, Baoding 071002, China Correspondence should be addressed to Feng Zhang, [email protected] Received 5 December 2011; Accepted 25 December 2011 Academic Editors: C. L. Frank and C. P. Wheater Copyright © 2012 J.-F. Hu and F. Zhang. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. One new species belonging to Anatemnus Beier is reported from China under the name A. chaozhouensis sp. nov. 1. Introduction optical microscope. Temporary slide mounts were made in glycerol. The pseudoscorpions genus Anatemnus belongs to subfamily The following abbreviations are used in the text for Atemninae, family Atemnidae. It was erected by Beier in 1932 trichobothria—b: basal; sb: sub-basal; st: sub-terminal; t: for the type species Chelifer javanus Thorell, 1883. This genus terminal; ib: interior basal; isb: interior sub-basal; ist: interior includes 18 known species which are widespread in Africa, sub-terminal; it: interior terminal; eb: exterior basal; esb: Americas, and Asia. Most of them (11 species) distribute in exterior sub-basal; est: exterior sub-terminal; et: exterior Southeast Asia, and only one -

Pseudoscorpiones: Atemnidae) from Europe and Asia

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 11 (2): 316-323 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2015 Article No.: 151303 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html The identity of pseudoscorpions of the genus Diplotemnus (Pseudoscorpiones: Atemnidae) from Europe and Asia János NOVÁK1,* and Mark S. HARVEY2,3,4 1. Eötvös Loránd University, Department of Systematic Zoology and Ecology, H-1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/C, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 2. Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia, E-mail: [email protected] 3. Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History; California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, SUA. 4. School of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia 6009, Australia. * Corresponding author, J. Novák, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 14. January 2014 / Accepted: 11. April 2015 / Available online: 07. November 2015 / Printed: December 2015 Abstract. Chelifer söderbomi Schenkel, 1937 (n. syn.), Diplotemnus insolitus Chamberlin, 1933 (n. syn.), Diplotemnus vachoni Dumitresco & Orghidan, 1969 (n. syn.) and Miratemnus piger var. sinensis Schenkel, 1953 (n. syn.) are proposed as junior synonyms of Chelifer balcanicus Redikorzev, 1928 which is newly transferred from Rhacochelifer, forming the new combination Diplotemnus balcanicus (Redikorzev, 1928) (n. comb). The species is reported from Hungary for the first time. The morphometric and morphological characters of specimens from Hungary and Romania are documented, and new illustrations are given. Key words: pseudoscorpions, Atemnidae, synonymy, new records, Hungary. Introduction nated several species as synonyms of D. insolitus. The aim of the present study is to investigate The pseudoscorpion genus Diplotemnus Chamber- the morphological and morphometric characters lin, 1933 belongs to the subfamily Miratemninae of some D. -

Exploring Outcomes of Children and Young People in Kinship Care in South Wales

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Exploring outcomes of children and young people in kinship care in South Wales Pratchett, Rebecca How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Pratchett, Rebecca (2018) Exploring outcomes of children and young people in kinship care in South Wales. Doctoral thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa45015 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Exploring outcomes of children and young people in kinship care in South Wales. Rebecca Pratchett Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the programme of Doctor of Philosophy. Swansea University 2017 i Abstract Around 30,000 young people enter care every year, with more than a fifth of those being placed with a relative or close family friend in kinship care. Literature has suggested that kinship care may be a positive avenue for providing alternative out-of-home care to young people in a cost-effective manner. -

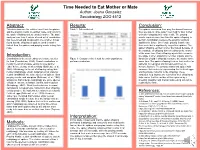

Time Needed to Eat Mother Or Mate Methods

Time Needed to Eat Mother or Mate Author: Joana Gonzalez Sociobiology ZOO 4512 Abstract: Results: Conclusion: This data observes the relative time it took for spiders Table 1: Data collected The spiders consumed their prey the slowest because and the praying mantis to eat their mate, and how long they are able to “store away” their food for later in their the spider offspring took to eat their mother. The data web after wrapping their mate in silk. The praying analyzed was from 3 videos of each act of cannibalism mantis requires more time than the spider offspring to that were timed and compared to one another. It was perform cannibalism because the praying mantis is found that the offspring of spiders eat their mother significantly larger. One female praying mantis eats fastest than the spiders and praying mantis eating their their mate that is significantly larger than spiders. The mate. spider offspring eat their mother the fastest because of the multitude of offspring that is feeding on the mother at the same time. Each offspring injects their venom in Introduction: the single mother, dissolving her inner organs, and the Cannibalism is the act of eating one’s same species Figure 1: Compares time it took for each organism to hundreds of spider offspring consume the mother at the for food (Cannibalism, 2020). Sexual cannibalism is perform cannibalism same time. The spider offspring feed on their mother for mostly the act of a female eating its male partner nutrients to help grow and to help teach them to either before, during, or after mating (Birkhead, et. -

Ostrovsky Et 2016-Biological R

Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm Andrew Ostrovsky, Scott Lidgard, Dennis Gordon, Thomas Schwaha, Grigory Genikhovich, Alexander Ereskovsky To cite this version: Andrew Ostrovsky, Scott Lidgard, Dennis Gordon, Thomas Schwaha, Grigory Genikhovich, et al.. Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm. Biological Reviews, Wiley, 2016, 91 (3), pp.673-711. 10.1111/brv.12189. hal-01456323 HAL Id: hal-01456323 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01456323 Submitted on 4 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Biol. Rev. (2016), 91, pp. 673–711. 673 doi: 10.1111/brv.12189 Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm Andrew N. Ostrovsky1,2,∗, Scott Lidgard3, Dennis P. Gordon4, Thomas Schwaha5, Grigory Genikhovich6 and Alexander V. Ereskovsky7,8 1Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Universitetskaja nab. 7/9, 199034, Saint Petersburg, Russia 2Department of Palaeontology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy, Geozentrum,