Monthly Observer's Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 13 2016 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting President’s Message Saturday, August 13th 2016 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho. Public Star Party Follows at the Colleagues, Centennial Observatory Club Officers It's that time of year: The City of Rocks Star Party. Set for Friday, Aug. 5th, and Saturday, Aug. 6th, the event is the gem of the MVAS year. As we've done every Robert Mayer, President year, we will hold solar viewing at the Smoky Mountain Campground, followed by a [email protected] potluck there at the campground. Again, MVAS will provide the main course and 208-312-1203 beverages. Paul McClain, Vice President After the potluck, the party moves over to the corral by the bunkhouse over at [email protected] Castle Rocks, with deep sky viewing beginning sometime after 9 p.m. This is a chance to dig into some of the darkest skies in the west. Gary Leavitt, Secretary [email protected] Some members have already reserved campsites, but for those who are thinking of 208-731-7476 dropping by at the last minute, we have room for you at the bunkhouse, and would love to have to come by. Jim Tubbs, Treasurer / ALCOR [email protected] The following Saturday will be the regular MVAS meeting. Please check E-mail or 208-404-2999 Facebook for updates on our guest speaker that day. David Olsen, Newsletter Editor Until then, clear views, [email protected] Robert Mayer Rick Widmer, Webmaster [email protected] Magic Valley Astronomical Society is a member of the Astronomical League M-51 imaged by Rick Widmer & Ken Thomason Herrett Telescope Shotwell Camera https://herrett.csi.edu/astronomy/observatory/City_of_Rocks_Star_Party_2016.asp Calendars for August Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 New Moon City Rocks City Rocks Lunation 1158 Castle Rocks Castle Rocks Star Party Star Party Almo, ID Almo, ID 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 MVAS General Mtg. -

Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects

Juliana Crestani Ribeiro de Souza Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects Porto Alegre 2017 Juliana Crestani Ribeiro de Souza Spatial Distribution of Galactic Globular Clusters: Distance Uncertainties and Dynamical Effects Dissertação elaborada sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Eduardo Luis Damiani Bica, co- orientação do Prof. Dr. Charles José Bon- ato e apresentada ao Instituto de Física da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul em preenchimento do requisito par- cial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Física. Porto Alegre 2017 Acknowledgements To my parents, who supported me and made this possible, in a time and place where being in a university was just a distant dream. To my dearest friends Elisabeth, Robert, Augusto, and Natália - who so many times helped me go from "I give up" to "I’ll try once more". To my cats Kira, Fen, and Demi - who lazily join me in bed at the end of the day, and make everything worthwhile. "But, first of all, it will be necessary to explain what is our idea of a cluster of stars, and by what means we have obtained it. For an instance, I shall take the phenomenon which presents itself in many clusters: It is that of a number of lucid spots, of equal lustre, scattered over a circular space, in such a manner as to appear gradually more compressed towards the middle; and which compression, in the clusters to which I allude, is generally carried so far, as, by imperceptible degrees, to end in a luminous center, of a resolvable blaze of light." William Herschel, 1789 Abstract We provide a sample of 170 Galactic Globular Clusters (GCs) and analyse its spatial distribution properties. -

Galactic Astronomy with AO: Nearby Star Clusters and Moving Groups

Galactic astronomy with AO: Nearby star clusters and moving groups T. J. Davidgea aDominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, BC Canada ABSTRACT Observations of Galactic star clusters and objects in nearby moving groups recorded with Adaptive Optics (AO) systems on Gemini South are discussed. These include observations of open and globular clusters with the GeMS system, and high Strehl L observations of the moving group member Sirius obtained with NICI. The latter data 2 fail to reveal a brown dwarf companion with a mass ≥ 0.02M in an 18 × 18 arcsec area around Sirius A. Potential future directions for AO studies of nearby star clusters and groups with systems on large telescopes are also presented. Keywords: Adaptive optics, Open clusters: individual (Haffner 16, NGC 3105), Globular Clusters: individual (NGC 1851), stars: individual (Sirius) 1. STAR CLUSTERS AND THE GALAXY Deep surveys of star-forming regions have revealed that stars do not form in isolation, but instead form in clusters or loose groups (e.g. Ref. 25). This is a somewhat surprising result given that most stars in the Galaxy and nearby galaxies are not seen to be in obvious clusters (e.g. Ref. 31). This apparent contradiction can be reconciled if clusters tend to be short-lived. In fact, the pace of cluster destruction has been measured to be roughly an order of magnitude per decade in age (Ref. 17), indicating that the vast majority of clusters have lifespans that are only a modest fraction of the dynamical crossing-time of the Galactic disk. Clusters likely disperse in response to sudden changes in mass driven by supernovae and stellar winds (e.g. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Effemeridi Astronomiche Di Milano Per L'anno

Informazioni su questo libro Si tratta della copia digitale di un libro che per generazioni è stato conservata negli scaffali di una biblioteca prima di essere digitalizzato da Google nell’ambito del progetto volto a rendere disponibili online i libri di tutto il mondo. Ha sopravvissuto abbastanza per non essere più protetto dai diritti di copyright e diventare di pubblico dominio. Un libro di pubblico dominio è un libro che non è mai stato protetto dal copyright o i cui termini legali di copyright sono scaduti. La classificazione di un libro come di pubblico dominio può variare da paese a paese. I libri di pubblico dominio sono l’anello di congiunzione con il passato, rappresentano un patrimonio storico, culturale e di conoscenza spesso difficile da scoprire. Commenti, note e altre annotazioni a margine presenti nel volume originale compariranno in questo file, come testimonianza del lungo viaggio percorso dal libro, dall’editore originale alla biblioteca, per giungere fino a te. Linee guide per l’utilizzo Google è orgoglioso di essere il partner delle biblioteche per digitalizzare i materiali di pubblico dominio e renderli universalmente disponibili. I libri di pubblico dominio appartengono al pubblico e noi ne siamo solamente i custodi. Tuttavia questo lavoro è oneroso, pertanto, per poter continuare ad offrire questo servizio abbiamo preso alcune iniziative per impedire l’utilizzo illecito da parte di soggetti commerciali, compresa l’imposizione di restrizioni sull’invio di query automatizzate. Inoltre ti chiediamo di: + Non fare un uso commerciale di questi file Abbiamo concepito Google Ricerca Libri per l’uso da parte dei singoli utenti privati e ti chiediamo di utilizzare questi file per uso personale e non a fini commerciali. -

Virgo the Virgin

Virgo the Virgin Virgo is one of the constellations of the zodiac, the group tion Virgo itself. There is also the connection here with of 12 constellations that lies on the ecliptic plane defined “The Scales of Justice” and the sign Libra which lies next by the planets orbital orientation around the Sun. Virgo is to Virgo in the Zodiac. The study of astronomy had a one of the original 48 constellations charted by Ptolemy. practical “time keeping” aspect in the cultures of ancient It is the largest constellation of the Zodiac and the sec- history and as the stars of Virgo appeared before sunrise ond - largest constellation after Hydra. Virgo is bordered by late in the northern summer, many cultures linked this the constellations of Bootes, Coma Berenices, Leo, Crater, asterism with crops, harvest and fecundity. Corvus, Hydra, Libra and Serpens Caput. The constella- tion of Virgo is highly populated with galaxies and there Virgo is usually depicted with angel - like wings, with an are several galaxy clusters located within its boundaries, ear of wheat in her left hand, marked by the bright star each of which is home to hundreds or even thousands of Spica, which is Latin for “ear of grain”, and a tall blade of galaxies. The accepted abbreviation when enumerating grass, or a palm frond, in her right hand. Spica will be objects within the constellation is Vir, the genitive form is important for us in navigating Virgo in the modern night Virginis and meteor showers that appear to originate from sky. Spica was most likely the star that helped the Greek Virgo are called Virginids. -

![Arxiv:2012.05245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 May 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2914/arxiv-2012-05245v2-astro-ph-ga-5-may-2021-642914.webp)

Arxiv:2012.05245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 May 2021

Draft version May 6, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 Charting the Galactic acceleration field I. A search for stellar streams with Gaia DR2 and EDR3 with follow-up from ESPaDOnS and UVES Rodrigo Ibata 1 | Khyati Malhan 2 | Nicolas Martin 1, 3 | Dominique Aubert1 | Benoit Famaey 1 | Paolo Bianchini 1 | Giacomo Monari 1 | Arnaud Siebert 1 | Guillaume F. Thomas 4, 5 | Michele Bellazzini 6 | Piercarlo Bonifacio7 | Elisabetta Caffau7 | Florent Renaud 8 | arXiv:2012.05245v2 [astro-ph.GA] 5 May 2021 1Universit´ede Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550, F-67000 Strasbourg, France 2The Oskar Klein Centre, Department of Physics, Stockholm University, AlbaNova, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden 3Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstronomie, K¨onigstuhl17, D-69117, Heidelberg, Germany 4Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, E-38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 5Universidad de La Laguna, Dpto. Astrof´ısica, E-38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 6INAF - Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, via Gobetti 93/3, I-40129 Bologna, Italy 7GEPI, Observatoire de Paris, Universit´ePSL, CNRS, 5 Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France 8Department of Astronomy and Theoretical Physics, Lund Observatory, Box 43, 221 00 Lund, Sweden Corresponding author: Rodrigo Ibata [email protected] 2 Ibata et al. Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT We present maps of the stellar streams detected in the Gaia Data Release 2 (DR2) and Early Data Release 3 (EDR3) catalogs using the STREAMFINDER algorithm. We also report the spectroscopic follow-up of the brighter DR2 stream members obtained with the high-resolution CFHT/ESPaDOnS and VLT/UVES spectrographs as well as with the medium-resolution NTT/EFOSC2 spectrograph. -

Desert Skies

Desert Skies Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association Volume LII, Number 7 July, 2006 Dark globule in the emission nebula IC 1396 contains never-before-seen young stars ♦ Learn about the Spitzer Infrared ♦ Websites: Gimme Shelter Part 4 Telescope ♦ Object of the Month ♦ Star parties and Meetings ♦ Constellation of the month Desert Skies: July, 2006 2 Volume LII, Number 7 Cover Photo: The Spitzer image of this globule is in spectacular contrast to the view seen in visible light. Spitzer's infra- red detectors unveiled the brilliant hidden interior of this opaque cloud of gas and dust for the first time, exposing never- before-seen young stars. Image: http://sscws1.ipac.caltech.edu/Imagegallery/image.php?image_name=ssc2003-06b TAAA Web Page: http://www.tucsonastronomy.org TAAA Phone Number: (520) 792-6414 Office/Position Name Phone E-mail Address President Bill Lofquist 297-6653 [email protected] Vice President Ken Shaver 762-5094 [email protected] Secretary Steve Marten 307-5237 [email protected] Treasurer Terri Lappin 977-1290 [email protected] Member-at-Large George Barber 822-2392 [email protected] Member-at-Large JD Metzger 760-8248 [email protected] Member-at-Large Teresa Plymate 883-9113 [email protected] Chief Observer Wayne Johnson 586-2244 [email protected] AL Correspondent (ALCor) Nick de Mesa 797-6614 [email protected] Astro-Imaging SIG Steve Peterson 762-8211 [email protected] Computers in Astronomy SIG Roger Tanner -

ESO Annual Report 2004 ESO Annual Report 2004 Presented to the Council by the Director General Dr

ESO Annual Report 2004 ESO Annual Report 2004 presented to the Council by the Director General Dr. Catherine Cesarsky View of La Silla from the 3.6-m telescope. ESO is the foremost intergovernmental European Science and Technology organi- sation in the field of ground-based as- trophysics. It is supported by eleven coun- tries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Created in 1962, ESO provides state-of- the-art research facilities to European astronomers and astrophysicists. In pur- suit of this task, ESO’s activities cover a wide spectrum including the design and construction of world-class ground-based observational facilities for the member- state scientists, large telescope projects, design of innovative scientific instruments, developing new and advanced techno- logies, furthering European co-operation and carrying out European educational programmes. ESO operates at three sites in the Ataca- ma desert region of Chile. The first site The VLT is a most unusual telescope, is at La Silla, a mountain 600 km north of based on the latest technology. It is not Santiago de Chile, at 2 400 m altitude. just one, but an array of 4 telescopes, It is equipped with several optical tele- each with a main mirror of 8.2-m diame- scopes with mirror diameters of up to ter. With one such telescope, images 3.6-metres. The 3.5-m New Technology of celestial objects as faint as magnitude Telescope (NTT) was the first in the 30 have been obtained in a one-hour ex- world to have a computer-controlled main posure. -

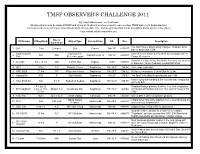

The 2011 Observers Challenge List

TMSP OBSERVER'S CHALLENGE 2011 By Kreig McBride and Tom Masterson All observations must be made at TMSP and 25 out of 30 objects must be viewed to earn a unique TMSP Observer's Award lapel pin. You must create a record of your observations which include date, time, instruments used and a brief description and/or sketch of the object. Your records will be returned to you. Size or ID Number V Magnitude Object Type Constellation RA Dec Description Separation The Sun! View 2 days noting changes. H-alpha, white 1 Sol -28m ½ degree Star Cancer 08h 39' +27d 07' light or projection is OK North Galactic Astronomical Catch this one before it sets. Next to the double star 31 2 N/A N/A Coma Berenices 12h 51' +27d 07' Pole Reference point Comae Berenices Omicron-2 a wide 4.9m, 9m double lies close by as does 3 U Cygni 5.9 – 12.1m N/A Carbon Star Cygnus 19.6h +47d 54' 6” diameter, 12.6m Planetary nebula NGC6884 4 M22 5.1m 7.8' Globular Cluster Sagittarius 18h 36.4' -23d 54' Rich, large and bright 5 NGC 6629 11.3m 15” Planetary Nebula Sagittarius 18h 25.7' -23d 12' Stellar at low powers. Central Star is 12.8m 6 Barnard 86 N/A 5' Dark Nebula Sagittarius 18h 03' -27d 53' “Ink Spot” Imbedded in spectacular star field Faint 1' glow surrounding 9.5m star w/a faint companion 7 NGC 6589-90 N/A 5' x 3' Reflection Nebula Sagittarius 18h 16.9'' -19d 47' 25” to its SW A 3.2m, B Reddish/Orange primary, B white, C is 10m companion 8 ETA Sagittarii 3.6m, C 10m, AB pair 3.6” Quadruple Star Sagittarius 18h 17.6' -36d 46' 93” distant at PA303d and D is 13m star 33” -

Spiral Galaxies Like the Milky Way and Andromeda Edge on and Face On

Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda Edge on and face on L of Milky Way ~ few x 10 10 Lsun SDSS image by D. Hogg The Sombrero galaxy 12 kpc 40,000 light years Cartoon of the edge‐on Milky Way galaxy Palomar 5 M5 M13 M15 Images of globular clusters (GCs) (Sloan Digital Sky Survey) Leo I Dwarf Galaxy A galaxy that has 1/10 or fewer the number of stars in a Milky Way sized galaxy Dwarf galaxies Halo of dark maer 250 kpc 800,000 LY Large Magellanic cloud Wei‐Hao Wan, UH image credit (Giant) ellipcal galaxies This type of galaxy is oen found at the centers of galaxy clusters Ellipcal galaxies have relavely less gas, dust, and star formaon than spiral galaxies. They look redder because the ages of their stars are on average older than the stars in a spiral galaxy It is believed that a 2 billion solar mass black hole lives at the center of M87. Electrons accelerang along the strong magnec field near the black hole produce this jet of light and charged parcles. Irregular galaxies forming lots of stars and/or interacng with other galaxies Large Magellanic Cloud – luminosity ~ 1/10 luminosity of the Milky Way The Mice Galaxies Many galaxies live in clusters or groups Hickson Group 87 Image taken at Gemini South Abell Cluster S0740 Image was obtained with the Hubble Space Telescope Map of the Local Group Of Galaxies A dozens of dwarf galaxies and 2 giant spirals (the Milky Way and Andromeda) NGC 205 image credit: www.noao.edu ~ 1/40 Milky Way luminosity Image credit: David W. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study.