Jarlath Killeen.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 20, Tuam Author

Digital content from: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), no. 20, Tuam Author: J.A. Claffey Editors: Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie, Jacinta Prunty Consultant editor: J.H. Andrews Cartographic editor: Sarah Gearty Editorial assistants: Angela Murphy, Angela Byrne, Jennnifer Moore Printed and published in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2 Maps prepared in association with the Ordnance Survey Ireland and Land and Property Services Northern Ireland The contents of this digital edition of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 20, Tuam, is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Referencing the digital edition Please ensure that you acknowledge this resource, crediting this pdf following this example: Topographical information. In J.A. Claffey, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 20, Tuam. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2009 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 4 February 2016), text, pp 1–20. Acknowledgements (digital edition) Digitisation: Eneclann Ltd Digital editor: Anne Rosenbusch Original copyright: Royal Irish Academy Irish Historic Towns Atlas Digital Working Group: Sarah Gearty, Keith Lilley, Jennifer Moore, Rachel Murphy, Paul Walsh, Jacinta Prunty Digital Repository of Ireland: Rebecca Grant Royal Irish Academy IT Department: Wayne Aherne, Derek Cosgrave For further information, please visit www.ihta.ie TUAM View of R.C. cathedral, looking west, 1843 (Hall, iii, p. 413) TUAM Tuam is situated on the carboniferous limestone plain of north Galway, a the turbulent Viking Age8 and lends credence to the local tradition that ‘the westward extension of the central plain. It takes its name from a Bronze Age Danes’ plundered Tuam.9 Although the well has disappeared, the site is partly burial mound originally known as Tuaim dá Gualann. -

Creating, Transmitting and Maintaining Handed-Down Memories of the Emergency in Ireland

Études irlandaises 46-1 | 2021 Passer au crible les traces du passé : modèles, cadres et métaphores The War That Never Came: Creating, Transmitting and Maintaining Handed-Down Memories of the Emergency in Ireland. Acknowledging Family Recollections of WWII Patrick Gormally Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/10759 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.10759 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Caen Printed version Date of publication: 8 July 2021 Number of pages: 143-167 ISBN: 978-2-38185-030-6 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Patrick Gormally, “The War That Never Came: Creating, Transmitting and Maintaining Handed-Down Memories of the Emergency in Ireland. Acknowledging Family Recollections of WWII”, Études irlandaises [Online], 46-1 | 2021, Online since 08 July 2021, connection on 10 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/10759 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesirlandaises. 10759 Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. The War That Never Came: Creating, Transmitting and Maintaining Handed- Down Memories of the Emergency in Ireland. Acknowledging Family Recollections of WWII 1 Abstract: Within the context of WWII, this essay explores the notion of national and personal conflict within individuals and communities in Ireland, part of which had undergone the severing of imperial connections and the attainment of national independence less than a full generation before. In Ireland, the conflict of war on a wider stage impinged upon an inner conflict closer to the heart. To go or not to go… to war. -

Cycling Ireland Rider Standings A4 15/07/2021 First Name Last Name

Cycling Ireland Rider Standings A4 15/07/2021 First Name Last Name Club Competition Category Total Points Jason O Toole South-East Road Club A4 12 Thomas Warke Ballymoney CC A4 12 Mark Pinfield Blarney Cycling Club A4 12 Alan Killian St Tiernans Cycling Club A4 12 Kieran Meehan Clogher Valley Wheelers A4 12 Luke Higgins Ballycastle CC A4 12 Patrick Sweeney Newcastle West Cycling Club A4 12 Shane Flynn Tralee Manor West BC A4 12 Vincent Doherty Bottecchia Racing Club A4 12 Piotr Zietala Roe Valley CC A4 12 Matthew Kinkaid Newry Wheelers CC A4 12 Ryan Annett Yeats Country Cycling Club A4 11 Michael O Dwyer Slievenamon Cycling Club A4 11 Declan Rafferty Cuchulainn CC A4 11 Andy Grehan Lucan Cycling Road Club A4 11 Ronan Burke Galway Bay CC A4 11 Justin Bloomer Harps CC A4 11 Alan Allman Redmond Orwell Wheelers Cycling Club A4 11 Jonathan Compston Shelbourne/Orchard CC A4 11 Padraic O’Flynn Orwell Wheelers Cycling Club A4 11 Chris Kelly Lakeland A4 11 David Robinson Kings Moss CC A4 10 Peter Elliott Velo Club Iveagh A4 10 Richard Gamble Velo Club Iveagh A4 10 Jonathan Hayes Portadown Cycling Club A4 10 Louis Freiter Fingal Road Racing Club A4 10 David Hayes TEAM BIKEWORX Celbridge A4 10 Pat Breen Tipp Wheelers A4 10 John McCarthy Islandeady Cycling Club A4 10 James Delaney Lucan Cycling Road Club A4 10 John White Un-Attached Leinster A4 10 Ronan O Grady CKR Cycling Club A4 10 Page 1 of 30 Cycling Ireland Rider Standings A4 15/07/2021 First Name Last Name Club Competition Category Total Points Brendan Brosnan Abbeyfeale Cycling Club A4 10 Chris -

Gaelic Football in Cleveland—A Timeline

Gaelic Football in Cleveland—A Timeline Notice of a The Shamrock Club match at an formed in the mid- Irish picnic in 1920_ 1920s. Managed by 1920 is among _1927 Frank Gallagher, they early references played Gaelic football to the sport in on an exhibition basis local papers in and competed nationally the 1920s. Phil in an amateur soccer McGovern was league. The soccer team a prime mover included players of behind Gaelic various nationalities. football in the Their home field was at 1920s. 1934_ W. 60th and Herman Henry Cavanagh sought like-minded compatriots and began to promote the organization of a GAA football _1941 team soon after his arrival in Cleveland in 1930. By 1934 the Cleveland “all–star” team was playing a full slate of games against clubs from other Midwest cities. However, play was put on hold in 1936, due to the Depression—along with immigration restrictions. The Cleveland Shamrocks played Gaelic football and soccer into the 1940s. The 1941 team, which made it to the Western amateur soccer finals, is pictured here. Back row, standing, L to R: Tom Worsley, John McKenny, Art Pilken, Julius Balough, Bill Wodowitz, James Cooney, Frank Gallagher, Martin Cooney, Pete McLaughlin, Blacky Gardner, Frank Newell, John Reiner, ?, Front row, kneeling, L to R: Jack Gallagher, Mike McLaughlin, Jim Steel, Marty McLaughlin, John Wodowitz, ?, Hugh Gallagher, Tony McGinty. The Cooney and McLaughlin brothers and Jim Steel were among those who also played on GAA teams. 1948_ _1950s New Irish-born players arrived on the scene throughout the 1950s, as newspaper accounts of the day record. -

University and College Officers

University and College Officers Chancellor of the University Mary Terese Winifred Robinson, M.A., LL.B., LL.M. (HARV.), D.C.L. (by diploma OXON.), LL.D. (h.c. BASLE, BELF., BROWN, CANTAB., COL., COVENTRY, DUBL., FORDHAM, HARV., KYUNG HEE (SEOUL), LEUVEN, LIV., LOND., MELB., MONTPELLIER, N.U.I., N.U. MONGOLIA, POZNAN, ST AND., TOR., UPPSALA, WALES, YALE), D.P.S. (h.c. NORTHEASTERN), DOCTORAT EN SCIENCES HUMAINES (h.c. RENNES, ALBERT SCHWEITZER (GENEVA)), D.PHIL. (h.c. D.C.U., D.I.T.), D.UNIV. (h.c. COSTA RICA, EDIN., ESSEX), HON. FIEI, F.R.C.P.I. (HON.), HON. F.R.C.S.I., HON. F.R.C.PSYCH., HON. F.R.C.O.G., F.R.S.A., M.R.I.A., M.A.P.S. Pro-Chancellors of the University Sir Anthony O’Reilly, B.C.L. (N.U.I.), PH.D. (BRAD.), LL.D. (h.c. ALLEGHENY COLLEGE, CARNEGIE MELLON, DE PAUL, DUBL., LEIC., WHEELING COLLEGE), D.C.L. (h.c. INDIANA STATE), D.ECON.SC. (h.c. N.U.I.), D.SC. (ECON.) (h.c. BELF.), D.UNIV. (h.c. BRAD., OPEN), D.B.A. (h.c. BOSTON COLLEGE, WESTMINSTER COLLEGE), D.BUS.ST. (h.c. ROLLINS COLLEGE), HON. F.I.M.I. The Hon. Mrs Justice Susan Jane Gageby Denham, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. (COL.), LL.D. (h.c. BELF.) Eda Sagarra, M.A. (DUBL., N.U.I.), DR.PHIL. (VIENNA), LITT.D., M.R.I.A. Patrick James Anthony Molloy, B.B.S., P.M.D. (HARV.), LL.D. -

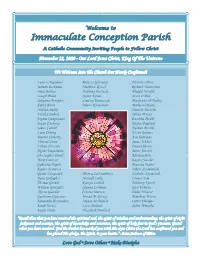

Immaculate Conception Parish

Welcome to Immaculate Conception Parish A Catholic Community Inviting People to Follow Christ November 22, 2020 - Our Lord Jesus Christ, King Of The Universe We Welcome Into The Church Our Newly Confirmed! Lauren Argamaso Rebecca Jalloway Nicholas Mroz Jarlath Beckman Matthew Kessel Richard Niemczura Nina Bednar Anthony Kostecki Abigail Nosalik Joseph Blaul Quinn Kovac Jason O'Dell Julianna Bonifazi Lindsey Krawczyk Mackenzie O'Malley Emily Breen Maeve Kristensen Madison Ozanic Nathan Burke Daniela Pacocha Frank Cambria Jillian Polena Sophia Campuzano Ewelina Predki Bryan Cardenas Haylee Pugliani James Carroll Nathan Reichle Liam Christy Alison Salinas Martin Cloherty Ava Santiago Vincent Curio James Schnier Lillian d'Escoto Daniel Sherry Skylar Daquilante James Shevlin Christopher Doud Adriana Solis Nora Emerson Kacper Sweder Gabriella Ergish Mariska Szabo Kaylee Fennessy Viktor Szumlanski Gavin Fitzgerald Theresa LaFramboise Nicholas Szymczak Ryan Gallagher Hannah Lally Emmet Tom Thomas Gentile Karsyn Liebich Anthony Tyrrell William Gonzalez Gianna Lohman Gael Urbieta Alyssa Guettler Colette Marzen Hailie Weaver Guillermo Guevara Sinead McGreevy Matthew Weisse Samantha Hernandez Maura McMahon Carter Wielgus Sarah Horist Luca Mellado Jaden Wierzba Kayla Hulne Elizabeth Miehlich “Recall then that you have received the spiritual seal, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of right judgment and courage, the spirit of knowledge and reverence, the spirit of holy fear in God’s presence. Guard what you have received. God the Father has marked you with His sign; Christ the Lord has confirmed you and has placed His pledge, the Spirit, in your hearts.”- Saint Ambrose of Milan Love God Serve Others Make Disciples Immaculate Conception Parish 2 Phase 2 Reopening Mass Schedule: Worship.. -

Bishop's Easter Message 2015

News from the Kilmore Diocesan Pastoral Centre Spring 2015 BISHOP’S EASTER MESSAGE 2015 According to the well-known rhyme, “Two men looked out from prison bars, one saw mud, the other stars”. It all depends on whether you look up or look down. The second reading of Mass on Easter Sunday urged us to look upwards: “Since you have been brought back to true life with Christ, you must look for the things that are in heaven, where Christ is, sitting at the right hand of God”. (Col.3:1) The reason we celebrate at Easter is not just because Christ rose from the dead in the distant past, but that we share in his resurrection. As Christians, we already share in the new life of Christ and we look forward Most Rev. Leo O’Reilly in hope to sharing the fullness of Christ's life in heaven. As risen people Bishop of Kilmore we look upwards; we have hope. We certainly need hope. In recent months world news has told us of wars and injustice, of unspeakable barbarities committed against people for no other reason than their Christian faith. Closer to home we are aware of families touched by the sudden death of a loved one and by other heart-breaking tragedies. We think of friends burdened by serious illness, of others still suffering the effects of crimes committed against them in the past. In a time of austerity many still struggle to make ends meet. For a lot of people it is hard to find reasons to hope. -

Register of Dentists As of 27 March 2020

Register of Dentists as of 27 March 2020 Registered Date Year Primary Registerable Surname First Name Number Registered Qualified Qualification Abbas Meriem 19317 28-Sep-17 2015 BDS NUIrel Abdalla Eyman 3915 02-Apr-15 2014 Dental Council Exam Abdel-Gadir Sali 5407 14-May-07 2004 BDS UWales Abdelhamid Ahmed 14516 21-Oct-16 2016 Dental Council Exam Abdelrahim Rawa 16916 01-Dec-16 2016 Dental Council Exam Abdelsalam Elsamani 6304 19-Jul-04 2004 Dental Council Exam Abdulrahim Mohammed 10807 09-Jul-07 2007 Dental Council Exam Abraham Shirley 5296 20-Sep-96 2002 Dental Council Exam Abu Farha Rami 18418 04-Oct-18 2017 Dentist Greece Abu Rabia Omar 616 18-Jan-16 2013 Dentist Romania Acornicesei Mihaela-Gabriela 12119 25-Jul-19 2008 Dentist Romania Adel Seyed Amir Reza 19118 19-Oct-18 2018 DMD UBudapest Adeyemi John 7004 23-Jul-04 2004 Dental Council Exam Adye-Curran John 7195 16-Oct-95 1981 BDentSc UDubl Afrasiabi Ali-Reza 15606 18-Dec-06 2006 BDentSc UDubl Aghasizadeh Sherbaf Reza 7317 01-Jun-17 2014 Dentist Hungary Agkhre Shkre 18318 18-Sep-17 2018 Dental Council Exam Agnew Hannah 13416 07-Oct-16 2015 BDS UDund Ahern Aidan 8018 19-Jun-18 2018 BDS NUIrel Ahern Catherine 4112 26-Jun-12 2012 BDS NUIrel Ahern David 4498 03-Jul-98 1998 BDentSc UDubl Ahern John 7310 14-Jul-10 2010 BDentSc UDubl Ahern John 5798 13-Jul-98 1998 BDentSc UDubl Aherne Christopher 2878 22-May-78 1974 BDS NUIrel Aherne John 4100 09-Jun-00 1996 BDS NUIrel Aherne Stuart 15101 17-Dec-01 2001 BDS UWales Ahmad Mustafa 2017 24-Feb-17 2014 Dentist Romania Ahmad Tanzeel 12317 23-Jun-17 -

Download CIEE Newsletter

Window to the Best CIEE Study Center in St. Petersburg, Russia December 2012 Newsletter #2 Greetings from snowy St. Petersburg! The holiday Student Involvement: Ruxi Zhang Chairs Model UN cheer is in the chilly Arctic air here in Russia’s Conference Northern Capital as our students take their exams and Ruxi Zhang (Macalester College) formed the first Model shop for last-minute souvenirs. The semester has UN Club at the Department of Political Science, SPbGU. been a joyful one: here are some highlights! “Kofi Annan, former Field Trip: Kiev + Moscow Secretary General of the UN and an alumnus of For the second year in a row, we explored the capitals my home university, has of Kiev and Moscow. For this field trip, we held an inspired me to pursue an essay contest, sponsored by our travel agent partners interest in international Tari Tour, for the two best descriptions of the five-day affairs. Since he withdrew from the Syria adventure. We received twelve submissions with mission, I have been some really wonderful quotes: wondering about possible solutions to the “Though I expected the Kiev-Moscow trip to be current impasse in the appealing for such unremarkable reasons as ceasefire negotiation. interesting history and architecture, I quickly came Chairing this committee to appreciate it for the aid it lent my imagination. I allowed me to learn can learn in many ways, but experiences are the several interesting and most useful. Going on the tours helped me not just thoughtful ideas for a to learn, but to care about what I was learning. -

Donnelly Vauxhall Tyrone Senior Football Championship

DONNELLY VAUXHALL TYRONE SENIOR FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP FINAL REPLAY 2016 SUNDAY 16TH OCTOBER 1.30 & 3.30pm Cluiche Ceannais Sinsear Contae Tír Eoghain COILL AN CHLOCHAIR v OILEÁN A’GHUAIL Tyrone Minor Hurling Championship Final PROUD SPONSORS OF THE EOGHAN RUADH v ÉIRE ÓG TYRONE CLUB CHAMPIONSHIPS £3/€3 Proud Sponsors of Tyrone GAA T: +44 (0) 28 8676 3741 W: mcaleer-rushe.co.uk WELCOME A CHAIRDE, MAR CHATHAOIRLEACH CHUMANN LUTHCHLEAS GAEL DE CHOISTE CHONTAE THÍR EOGHAIN, TÁ ÁTHAS AN DOMHAIN ORM FÁILTE A CHUR ROMHAIBH UILIG CHUIG PÁIRC UÍ HÉILÍ. Also today we have the Minor Club and our County sponsors as Hurlers of Éire Og and Eoghan often as you can. Ruadh doing battle in their Championship Final. Many of this The mini-games are played by particular crop of Minor Hurlers the children selected from the have made their own piece of competing clubs Coalisland, history for the County after Killyclogher, Eoghan Ruadh claiming a Minor C All Ireland title and Eire Og. Please show your in 2015 and competing in the ‘A’ appreciation to the children, our section of the Ulster League this stars of the future. year with the traditional big guns of Ulster Hurling. Like all Eoghan Match programmes have been part Ruadh v Éire Og County Finals, you of all our Championship matches RoisínCiarán Ní Mac Shiúrtáin Lochlainn, should expect a high intensity and and Underage Finals this year. Cathaoirleach, Tír Eoghain high quality battle. Congratulations to Eunan and our Tyrone County Chairman Communications committee on last It gives me great pleasure to It would be remiss of me not to week’s bumper programme and welcome you to Healy Park for wish our Junior Champions Rock another fine effort here today. -

Pos. First Name Surname Bib No. Category Club Time 1 Jarlath

Pos. First Name Surname Bib Category Club Time No. 1 Jarlath Falls 104 Male Open Ballymena and 33:26 Antrim 2 Desi Foley 120 Male Open 34:48 3 Matt Wray 83 Male 40-50 Ballymena and 35:50 Antrim 4 Aidan Hagan 143 Male Open Acorns 36:48 ACMagherafelt 5 Bliadhan Glass 115 Male Open Acorns 36:58 6 Bryan Edgar 32 Male 50-60 Springwell 37:00 Running Club 7 Darrell McKee 196 Male Open Acorn AC 37:08 8 Diarmuid O'Kane 159 Male Open ACORN AC 37:32 9 Jonathan Dempsey 192 Male 40-50 Acorns AC 37:37 10 Aaron Meharg 63 Male Open Acorns AC 37:40 11 Heather Foley 169 Female Open 38:30 12 Conor Toman 98 Male Open Team X 38:59 13 Patricia OHagan 180 Female Open St Peters Lurgan 39:09 14 Jonny Wilson 78 Male Open Tri Limits 39:22 15 Anne Paul 146 Female Open City of Derry 39:28 16 Thomas Doherty 55 Male 40-50 Termoneeny 39:53 17 John Hughes 128 Male 50-60 Termoneeny 40:21 18 Pauline McGurren 153 Female Open Sperrin Harriers 40:22 19 Gary O'Doherty 45 Male Open 40:57 20 Paddy McCormick 40 Male 40-50 Termoneeny 41:05 21 Eric Montgomery 53 Male 50-60 Lagan Valley 41:24 22 Frankie Devlin 41 Male 40-50 City of Lisburn 41:27 23 Brian Geddis 38 Male 50-60 Springwell 41:51 Running Club 24 Francis Stewart 134 Male 40-50 Magherafelt 42:02 Harriers 25 Adrian McCrystal 127 Male 40-50 42:14 26 Jason McShane 76 Male Open 42:20 27 Colin Hull 99 Male 40-50 42:24 28 Geraldine Quigley 152 Female Open Larne AC 42:45 29 Eamonn O'Kane 65 Male Open 42:47 30 Don Mulholland 173 Male 40-50 Termoneeny 42:54 31 Paul Mulgrew 82 Male 50-60 43:04 32 Richard Smith 93 Male Open Acorns -

Contextualising Immram Curaig Ua Corra

1 The Devil’s Warriors and the Light of the Sun: Contextualising Immram Curaig Ua Corra Master’s thesis in Celtic Studies K. Eivor Bekkhus 2013 Jan Erik Rekdal, professor in Irish Studies at the Institute for Linguistic and Nordic Studies, University of Oslo, was the supervisor for this thesis. 2 Contents 1. Preludes to a Voyage 1.1 The frame story of Immram Curaig Ua Corra 1.2 Heathen ways 1.3 The Devil’s warriors 1.4 Women 1.5 Judgement 1.6 Mixed agendas 1.7 The flaithbrugaid of Connacht 1.8 From bruiden to church 2. Saints and Villains 2.1 Lochán and Énna 2.2 Silvester 2.3 Énna of Aran 2.4 Findén 2.5 Moderated saints 2.6 Sea pilgrimages 3. The Uí Chorra and the Uí Fhiachrach Aidne 3.1 Hospitality and belligerence 3.2 The will of God 3.3 Jesters 3.4 Home of the Uí Chorra? 3.5 Comán 3.6 Attacks on Tuaim 3.7 Uí Fhiachrach Aidne in the 12th century 3.8 A hypothetical parable 3.9 The moral legacy of Guaire 4. Influences in Church and Society prior to the 12th Century 4.1 The Irish Church and learning 4.2 Céli Dé 3 4.3 Rome 4.4 Vikings 4.5 Canterbury 4.6 The Normans and William the Conqueror 4.7 Secularisation? 5. Immram Curaig Ua Corra and the 12th Century 5.1 Internal enemies 5.2 Kingship and church politics 5.3 Reformers 5.4 Succession at Armagh 5.5 Erenaghs and marriage 5.6 Violent crime 5.7 Archbishoprics and dioceses 5.8 Barbarious Connacht? 5.9 Locations in Immram Curaig Ua Corra 5.9.1 Tuaim 5.9.2 Clochar 5.9.3 Clonmacnoise and Clonard 5.9.4 Emly 5.9.5 Armagh 5.10 Restructuring Ireland 6.