Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Iranian Nomads in Western Central Asia

ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5 ANCIENT IRANIAN NOMADS IN. 1 ANCIENT IRANIAN NOMADS IN WESTERN CENTRAL ASIA* A. Abetekov and H. Yusupov Contents Literary sources on the ancient Iranian nomads of Central Asia ............ 25 Society and economy of the Iranian nomads of Central Asia .............. 26 Culture of the Iranian nomads of Central Asia ..................... 29 The territory of Central Asia, which consists of vast expanses of steppe-land, desert and semi-desert with fine seasonal pastures, was destined by nature for the development of nomadic cattle-breeding. Between the seventh and third centuries b.c. it was inhabited by a large number of tribes, called Scythians by the Greeks, and Sakas by the Persians. The history of the Central Asian nomads is inseparable from that of the nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppe zone. Their political and economic life was closely linked, and their material culture had much in common. It should also be noted that, despite their distinctive qualities, the nomadic tribes were closely connected with the agricultural population of Central Asia. In fact, the history and movements of these nomadic tribes and the settled population cannot be considered in isolation; each had its impact on the other, and this interdependence must be properly understood. * See Map 1. 24 ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5 Literary sources on the ancient Iranian. Literary sources on the ancient Iranian nomads of Central Asia The term ‘Tura’¯ 1 is the name by which the Central Asian nomadic tribes were in one of the earliest parts of the Avesta. The Turas¯ are portrayed as enemies of the sedentary Iranians and described, in Yašt XVII (prayer to the goddess Aši), 55–6, as possessing fleet-footed horses.2 As early as 641 or 640 b.c. -

Invented Herbal Tradition.Pdf

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 247 (2020) 112254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Inventing a herbal tradition: The complex roots of the current popularity of T Epilobium angustifolium in Eastern Europe Renata Sõukanda, Giulia Mattaliaa, Valeria Kolosovaa,b, Nataliya Stryametsa, Julia Prakofjewaa, Olga Belichenkoa, Natalia Kuznetsovaa,b, Sabrina Minuzzia, Liisi Keedusc, Baiba Prūsed, ∗ Andra Simanovad, Aleksandra Ippolitovae, Raivo Kallef,g, a Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172, Mestre, Venice, Italy b Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004, St Petersburg, Russia c Tallinn University, Narva rd 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia d Institute for Environmental Solutions, "Lidlauks”, Priekuļu parish, LV-4126, Priekuļu county, Latvia e A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 25a Povarskaya st, 121069, Moscow, Russia f Kuldvillane OÜ, Umbusi village, Põltsamaa parish, Jõgeva county, 48026, Estonia g University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, 12042, Pollenzo, Bra, Cn, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Currently various scientific and popular sources provide a wide spectrum of Epilobium angustifolium ethnopharmacological information on many plants, yet the sources of that information, as well as the in- Ancient herbals formation itself, are often not clear, potentially resulting in the erroneous use of plants among lay people or even Eastern Europe in official medicine. Our field studies in seven countries on the Eastern edge of Europe have revealed anunusual source interpretation increase in the medicinal use of Epilobium angustifolium L., especially in Estonia, where the majority of uses were Ethnopharmacology specifically related to “men's problems”. -

On Program and Abstracts

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO, CZECH REPUBLIC TENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY TIME AND MYTH: THE TEMPORAL AND THE ETERNAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 26-28, 2016 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic Conference Venue: Filozofická Fakulta Masarykovy University Arne Nováka 1, 60200 Brno PROGRAM THURSDAY, MAY 26 08:30 – 09:00 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING ADDRESSES VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA; IACM THURSDAY MORNING SESSION: MYTHOLOGY OF TIME AND CALENDAR CHAIR: VÁCLAV BLAŽEK 09:30 –10:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography & European University, St. Petersburg, Russia OLD WOMAN OF THE WINTER AND OTHER STORIES: NEOLITHIC SURVIVALS? 10:00 – 10:30 WIM VAN BINSBERGEN African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands 'FORTUNATELY HE HAD STEPPED ASIDE JUST IN TIME' 10:30 – 11:00 LOUISE MILNE University of Edinburgh, UK THE TIME OF THE DREAM IN MYTHIC THOUGHT AND CULTURE 11:00 – 11:30 Coffee Break 11:30 – 12:00 GÖSTA GABRIEL Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany THE RHYTHM OF HISTORY – APPROACHING THE TEMPORAL CONCEPT OF THE MYTHO-HISTORIOGRAPHIC SUMERIAN KING LIST 2 12:00 – 12:30 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia CULTIC CALENDAR AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME: ELEMENTS OF COMMON SEMANTICS IN EXPLANATORY AND ASTROLOGICAL TEXTS OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 12:30 – 13:00 ATTILA MÁTÉFFY Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey & Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, -

Manchu Grammar (Gorelova).Pdf

HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 1 MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 2 HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION EIGHT CENTRAL ASIA edited by LILIYA M. GORELOVA VOLUME SEVEN MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 3 MANCHU GRAMMAR EDITED BY LILIYA M. GORELOVA BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2002 HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 4 This book is printed on acid-free paper Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Gorelova, Liliya M.: Manchu Grammar / ed. by Liliya M. Gorelova. – Leiden ; Boston ; Köln : Brill, 2002 (Handbook of oriental studies : Sect.. 8, Central Asia ; 7) ISBN 90–04–12307–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gorelova, Liliya M. Manchu grammar / Liliya M. Gorelova p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section eight. Central Asia ; vol.7) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004123075 (alk. paper) 1. Manchu language—Grammar. I. Gorelova, Liliya M. II. Handbuch der Orientalis tik. Achte Abteilung, Handbook of Uralic studies ; vol.7 PL473 .M36 2002 494’.1—dc21 2001022205 ISSN 0169-8524 ISBN 90 04 12307 5 © Copyright 2002 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by E.J. Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

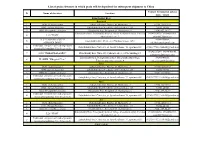

List of Grain Elevators in Which Grain Will Be Deposited for Subsequent Shipment to China

List of grain elevators in which grain will be deposited for subsequent shipment to China Contact Infromation (phone № Name of elevators Location num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky district, village Starotsuruhaytuy, Pertizan 89145160238, 89644638969, 4 LLS "PION" Shestakovich str., 3 [email protected] LLC "ZABAYKALSKYI 89144350888, 5 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 149/1 AGROHOLDING" [email protected] Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 6 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich 89242727249, 89144700140, 7 OOO "ZABAYKALAGRO" Zabaykalsky krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 147A, building 15 [email protected] Zabaykalsky krai, Priargunsky district, Staroturukhaitui village, 89245040356, 8 IP GKFH "Mungalov V.A." Tehnicheskaia street, house 4 [email protected] Corn 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 4 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich Rice 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. -

Gypsies in the Russian Empire (During the 18Th and First Half of the 19Th Century)

Population Processes, 2017, 2(1) Copyright © 2017 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Population Processes Has been issued since 2016. E-ISSN: 2500-1051 2017, 2(1): 20-34 DOI: 10.13187/popul.2017.2.20 www.ejournal44.com Gypsies in the Russian Empire (during the 18th and first half of the 19th century) Vladimir N. Shaidurov a , b , * a Saint-Petersburg Mining University (Mining University), Russian Federation b East European Historical Society, Russian Federation Abstract In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, historians continued to focus much attention on the history of minor ethnic groups, but the state of this body of knowledge is quite varied. Russian historical gypsiology is in its early stages of development. Progress is being slowed by limits of known written archives. So, one of the key objectives is to identify archival documents that will make it possible to set and address research goals. In this paper, we will introduce the options that were put forward for acting on and reacting to the situation of the Gypsies during the Russian Empire, both theorized on as well as put into practice between the 1780s and the 1850s. The situation of the Gypsies here refers to the relations between the Russian Empire, represented by the emperor and his bureaucratic organization, and the Gypsies who found themselves in its territory. The solution for the issues from the Gypsies’ point of view involved their rejection of traditional lifestyles and of integration into economic and social institutions during a particular historical period. -

Argus Russian Coal

Argus Russian Coal Issue 17-36 | Monday 9 October 2017 MARKET COmmENTARY PRICES Turkey lifts coal imports from Russia Russian coal prices $/t Turkey increased receipts of Russian thermal coal by 9pc on Delivery basis NAR kcal/kg Delivery period 6 Oct ± 29 Sep the year in January-August, to 7.79mn t, according to data fob Baltic ports 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 86.97 -0.20 from statistics agency Tuik, amid higher demand from utili- fob Black Sea ports 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 90.63 -0.25 ties and households. Russian material replaced supplies from cif Marmara* 6,000 Nov 17 100.33 0.33 South Africa, which redirected part of shipments to more fob Vostochny 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 100.00 1.00 profitable markets in Asia-Pacific this year. fob Vostochny 5,500 Nov-Dec 17 87.0 0 1.75 *assessment of Russian and non-Russian coal In August Russian coal receipts rose to over 1.26mn t, up by 15pc on the year and by around 19pc on the month. Russian coal prices $/t This year demand for sized Russian coal is higher com- Delivery basis NAR kcal/kg Delivery period Low High pared with last year because of colder winter weather in 2016-2017, a Russian supplier says. Demand for coal fines fob Baltic ports 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 85.25 88.00 fob Black Sea ports 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 89.50 91.00 from utilities has also risen amid the launch of new coal- fob Vostochny 6,000 Nov-Dec 17 100.00 100.00 fired capacity, the source adds. -

The 200-Years Crisis in Relation Between Parhae and Silla

Vol. 2, No. 1 Asian Culture and History Ritual and Diplomacy: The 200-Years Crisis in Relation between Parhae and Silla Alexander A. Kim Faculty of history, Ussuriysk State Pedagogic institute 692000, Russian Federation, t. Ussuriysk, Nekrasova St. 35, Russia Tel: 7-4234-346787 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The state of Parhae (in Chinese reading- Bohai) existed in what is now Russian Maritime region, North Korea and Northeastern China from the late 7th to the early 10th centuries AD. Parhae played a major role at relations between Silla, Japan and Chinese empire Tang. Of course, Parhae was subjected to important cultural influence from other countries and in some cases followed their ritual and diplomatic tradition. Many specialists from Japan, Russia, China and both Korean states have done research of different aspects of Parhae history and culture. However, many scholars have not paid attention to influence of ritual system at international relation of Parhae. In opinion of author, Parhae and Silla had antagonistic relation during 200 years because they could not agree about their respective vis-à-vis status each other. For example, Silla did not want to recognize Parhae as a sovereign state, which by recognized and independence state from China, but Silla was vassal of empire Tang. This article critically analyzes relation between Parhae and Silla for of the origin of conflict of between countries using Russian and Korean materials (materials by South and North Korean works). Keywords: History, Parhae (Bohai), Silla, Korea, Khitan 1. Situation before establishment of Bohai state and earliest periods of Bohai and Silla relations Parhae (in Chinese and Russian readings – Bohai, in Japanese reading- Bokkai) can be seen as a first state which existed in what is now Russian Far East, and this alone makes Parhae historically important. -

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society http://journals.cambridge.org/PPR Additional services for Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here New AMS Dating of Bone and Antler Weapons from the Shigir Collections Housed in the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum, Urals, Russia Svetlana Savchenko, Malcolm C. Lillie, Mikhail G. Zhilin and Chelsea E. Budd Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 81 / December 2015, pp 265 - 281 DOI: 10.1017/ppr.2015.16, Published online: 12 October 2015 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0079497X1500016X How to cite this article: Svetlana Savchenko, Malcolm C. Lillie, Mikhail G. Zhilin and Chelsea E. Budd (2015). New AMS Dating of Bone and Antler Weapons from the Shigir Collections Housed in the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum, Urals, Russia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 81, pp 265-281 doi:10.1017/ppr.2015.16 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/PPR, IP address: 150.237.205.20 on 27 Nov 2015 Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 81, 2015, pp. 265–281 © The Prehistoric Society doi:10.1017/ppr.2015.16 First published online 12 October 2015 New AMS Dating of Bone and Antler Weapons from the Shigir Collections Housed in the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum, Urals, Russia By SVETLANA SAVCHENKO1, MALCOLM C. LILLIE2, MIKHAIL G. ZHILIN3, and CHELSEA E. BUDD4 This paper presents new AMS dating of organic finds from the Shigir (Shigirsky) peat bog, located in the Sverdlovsk Province, Kirovgrad District of the Urals. The bog is located immediately south of the river Severnaya Shuraly, with the Urals to the west. -

Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY INSTITUTION OF SCIENCE VOLOGDA RESEARCH CENTER OF THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGES: FACTS, TRENDS, FORECAST Volume 11, Issue 5, 2018 The journal was founded in 2008 Publication frequency: six times a year According to the Decision of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, the journal Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast is on the List of peer-reviewed scientific journals and editions that are authorized to publish principal research findings of doctoral (candidate’s) dissertations in scientific specialties: 08.00.00 – economic sciences; 22.00.00 – sociological sciences. The journal is included in the following abstract and full text databases: Web of Science (ESCI), ProQuest, EBSCOhost, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), RePEc, Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, VINITI RAS, Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI). The journal’s issues are sent to the U.S. Library of Congress and to the German National Library of Economics. All research articles submitted to the journal are subject to mandatory peer-review. Opinions presented in the articles can differ from those of the editor. Authors of the articles are responsible for the material selected and stated. ISSN 2307-0331 (Print) ISSN 2312-9824 (Online) © VolRC RAS, 2018 Internet address: http://esc.vscc.ac.ru ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGES: FACTS, TRENDS, FORECAST A peer-reviewed scientific journal that covers issues of analysis and forecast of changes in the economy and social spheres in various countries, regions, and local territories. The main purpose of the journal is to provide the scientific community and practitioners with an opportunity to publish socio-economic research findings, review different viewpoints on the topical issues of economic and social development, and participate in the discussion of these issues. -

Reflection of Space-Time in Ancient Cultural Heritage of Urals*

Open Access Library Journal Reflection of Space-Time in Ancient * Cultural Heritage of Urals Alina Paranina Herzen State Pedagogical University, St. Petersburg, Russia Received 9 July 2016; accepted 1 August 2016; published 4 August 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Based on the example of Shigir idols, the article reviews the possibility of using the ancient sacred objects as tools for orientation in space-time (according to dating of C-14, the age of the Grand Shi- gir Idol is 11,000 years). Author’s reconstructions of solar navigation technology are justified by: paleo-astronomic and metrological calculations; reflection of curve of shadow of the gnomon dur- ing the year in the proportions of the body and face of anthropomorphic figures; comparison of geometric basics of “faces” of Shigir idols, masks of Okunev stelae in Khakassia and vertical sundi- al on the milestones of the eighteenth century in St. Petersburg. The results show a rational as- signment of objects of ancient culture. Keywords Ancient Cultural Heritage, Shigir Idols, Okunev Stelae, Sundial and Calendars, Orientation in Space-Time Subject Areas: Archaeology 1. Introduction Big Shigir Idol is the most ancient wooden sculpture in the world, made of larch in the Mesolithic (radiocarbon age of 11,000 years). It is stored in the Sverdlovsk regional museum in Yekaterinburg (Russia). Unique arc- haeological object was discovered in 1890 by workmen of Kurinskiy gold mine, at depth of 4 meters of peat deposits of drained part of the lake, on the eastern slope of the Middle Urals. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country.