Behind Closed Doors: Obstacles and Opportunities for Public Access to Myanmar's Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Conglomerates in the Context of Myanmar's Economic

Chapter 6 Business Conglomerates in the Context of Myanmar’s Economic Reform Aung Min and Toshihiro Kudo Abstract The purpose of this paper is to identify the role of conglomerates in the context of Myanmar’s economic reform process. The paper addresses the research question of the role of business conglomerates and the Myanmar economy, such as are they growth engines or just political cronies? We select some of the top conglomerates in Myanmar and assess their profile, performance, and strategies and examine the sources of growth and limitations for future growth and prospects. The top groups chosen for this paper are Htoo, Kanbawza, Max, Asia World, IGE, Shwe Taung, Serge Pun Associates (SPA)/First Myanmar Investment Group of Companies (FMI), Loi Hein, IBTC, Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), and Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEHL). There are other local conglomerates that this paper does not address and they include Shwe Than Lwin Group, Eden Group, Capital and Dagon International etc., which are suggested for further research about Myanmar’s conglomerates in the future. Sources of growth and key success factors of the top business groups are their connection with government, contact with foreign partners, and their competency in the past and present. In the context of the economic reform, previously favored business people appear to recognize that the risks of challenging economic reform could outweigh the likely benefits. In addition, some of the founders and top management of the conglomerates are still subject to US sanctions. Market openness, media monitoring, competition by local and foreign players, sanctions, and the changing trends of policy and the economy limit the growth of conglomerates. -

A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon

A Strategic A Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) UrbanDevelopment Plan of Greater The Republic of the Union of Myanmar A Strategic Urban Development Plan of Greater Yangon The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Yangon FINAL REPORT I Part-I: The Current Conditions FINAL REPORT I FINAL Part - I:The Current Conditions April 2013 Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. NJS Consultants Co., Ltd. YACHIYO Engineering Co., Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Inc. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. 2013 April ALMEC Corporation JICA EI JR 13-132 N 0 300km 0 20km INDIA CHINA Yangon Region BANGLADESH MYANMAR LAOS Taikkyi T.S. Yangon Region Greater Yangon THAILAND Hmawbi T.S. Hlegu T.S. Htantabin T.S. Yangon City Kayan T.S. 20km 30km Twantay T.S. Thanlyin T.S. Thongwa T.S. Thilawa Port & SEZ Planning調査対象地域 Area Kyauktan T.S. Kawhmu T.S. Kungyangon T.S. 調査対象地域Greater Yangon (Yangon City and Periphery 6 Townships) ヤンゴン地域Yangon Region Planning調査対象位置図 Area ヤンゴン市Yangon City The Project for the Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I The Project for The Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon Final Report I < Part-I: The Current Conditions > The Final Report I consists of three parts as shown below, and this is Part-I. 1. Part-I: The Current Conditions 2. Part-II: The Master Plan 3. Part-III: Appendix TABLE OF CONTENTS Page < Part-I: The Current Conditions > CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Study Period ............................................................................................................. -

FOR PARTICIPANTS ONLY 23 August 2013

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC FOR PARTICIPANTS ONLY 23 August 2013 Training of Trainer Programme on WTO and Trade Related Issues 19-23 August 2013 Yangon, Myanmar LIST OF PARTICIPANTS MYANMAR Ms. Thi Thi Oo, Assistant Director, Research Dpt. Union Supreme Court, Building 54, The Supreme Court of the Union, Supreme Court, Naypyidaw, Phone- 09 5066649 , Office-067 430335, Email: [email protected] Mr. Tint Swe, Manager, Myanmar Fishery Products, Processors and Exporters Association, Corner of Bayint Nawng Rd., Seikhmi Saywar (BPD) St., Insein T/S, Phone-644031/32, Email: [email protected] Mr. Tin Hla, Assistant Manager, Myanamr Fishery Product Processors & Exporter Association, Corner of Bayint Nawng Rd., Seikhmi Saywar (BPD) St., Insein T/S, Phone- 0973224693, Email: [email protected] Mr. Min Min Htet, Staff Officer, Union Attorney Generals Office, Building No. 25, Union Attorney Generals Office, Naypyidaw, Phone- 067 404171, Email: [email protected] Ms. Htay Htay Than, Deputy Director, Directorate of Industry, Ministry of Industry Buidling No. 37 Naypyidaw, Phone- 09420722306/067408129, Email: [email protected] Mr. Khin Maung Htwe, Assistant Director, Directorate Industrial Planning, Ministry of Industry, Ministry of industry, Bldg. 30 Naypyidaw, Phone- 067 405336, 09420702037, Email: [email protected] Ms. San San Lwin, Assistant Engineer, Telecommunication and Postal Training Centre, Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications; Ministry of Communication and Information Technology Telecommunication and Postal Training Centre, Lower Pazundaung Road, Yangon, Phone- 095002992, Email: [email protected] Mr. U Chan Maung Maung, Assistant Manager, Ministry of Transport, No. 10 Pansodan Street, Yangon, Phone- 095068979, Email: [email protected] Ms. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 210/Monday, October 31, 2016/Notices TREASURY—NBES FEE SCHEDULE—EFFECTIVE JANUARY 3, 2017

75488 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 210 / Monday, October 31, 2016 / Notices Federal Reserve System also charges a reflective of costs associated with the The fees described in this notice funds movement fee for each of these processing of securities transfers. The apply only to the transfer of Treasury transactions for the funds settlement off-line surcharge, which is in addition book-entry securities held on NBES. component of a Treasury securities to the basic fee and the funds movement Information concerning fees for book- transfer.1 The surcharge for an off-line fee, reflects the additional processing entry transfers of Government Agency Treasury book-entry securities transfer costs associated with the manual securities, which are priced by the will increase from $50.00 to $70.00. Off- processing of off-line securities Federal Reserve, is set out in a separate line refers to the sending and receiving transfers. Federal Register notice published by of transfer messages to or from a Federal Treasury does not charge a fee for the Federal Reserve. Reserve Bank by means other than on- account maintenance, the stripping and line access, such as by written, reconstitution of Treasury securities, the The following is the Treasury fee facsimile, or telephone voice wires associated with original issues, or schedule that will take effect on January instruction. The basic transfer fee interest and redemption payments. 3, 2017, for book-entry transfers on assessed to both sends and receives is Treasury currently absorbs these costs. NBES: TREASURY—NBES FEE SCHEDULE—EFFECTIVE JANUARY 3, 2017 [In dollars] Off-line Transfer type Basic fee surcharge On-line transfer originated ...................................................................................................................................... -

FIL-79-2008 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation August 13, 2008 550 17Th Street NW, Washington, D.C

Financial Institution Letter FIL-79-2008 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation August 13, 2008 550 17th Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20429-9990 OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons Summary: The Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control has added new entries to its Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list. Distribution: Highlights: FDIC-Supervised Banks (Commercial and Savings) • On July 29, 2008, the Department of the Treasury’s Office Suggested Routing: of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added new entries to its Chief Executive Officer Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons BSA Compliance Officer (SDN) list. • OFAC added 10 Burmese [BURMA] entities to the SDN list. Related Topics: Office of Foreign Assets Control • A complete list of the entries is attached. • OFAC information also may be found on the Internet at Attachment: http://www.treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac. New Entries List • For further information about Executive Orders, the list of blocked accounts or the procedures to block accounts, please call OFAC’s Compliance Programs Contact: Division at 1-800-540-6322. Anti-Money Laundering Specialist Marie Edwards at [email protected] or (202) 898-3673 Note: FDIC Financial Institution Letters (FILs) may be accessed from the FDIC's Web site at http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2008/index. html. To receive FILs electronically, please visit http://www.fdic.gov/about/subscriptions/fil.html. Paper copies of FDIC FILs may be obtained through the FDIC's Public Information Center, 3501 N. Fairfax Drive, Room E 1002, Arlington, VA 22226 (1-877-275-3342 or 703-562-2200). -

Medical Facilities in Burma DISCLAIMER

Medical Facilities in Burma DISCLAIMER: The U.S. Embassy in Rangoon, Burma assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by, the medical professionals, medical facilities or air ambulance services whose names appear on the following lists. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Embassy. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information in the list on professional credentials and areas of expertise are provided directly by the medical professional, medical facility or air ambulance service; the Embassy is not in a position to vouch for such information. You may receive additional information about the individuals and facilities on the list by contacting local medical boards and associations (or its equivalent) or local licensing authorities. Rangoon Private Hospitals Asia Royal Hospital 14 Baho Road, Sanchaung Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 538055 / (+95) 1 2304999 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.asiaroyalhospital.com/ Bumrungrad Clinic 77 Pyidaungsu Yeiktha Road, Dagon Township, Rangoon (+95) 1 2302420, 21, 22, 23 Website: www.bumrungrad.com/yangon-1 Note: Not open 24 hours International SOS Clinic Dusit Inya Lake Resort, 37 Kaba Aye Pagoda Road, Rangoon (+95) 1 657922 / (+95) 1 667866 Website: www.internationalsos.com/en/about-our-clinics_myanmar_3333.htm Pun Hlaing Siloam Hospital Pun Hlain Golf Estate Avenue, Hlaing Tharyar -

Political Prisoner Profile

Political Prisoner Profile AAPP CASE: Htin Kyaw NAME OF POLITICAL Htin Kyaw PRISONER: GENDER: Male Ethnicity: Burman DATE OF BIRTH: 1963 Age: 50 RELIGION: Buddhist PARENTS NAME: U Hlaing EDUCATION: ETEC (Mech) Leader of the Movement for Democracy Current Force OCCUPATION: (MDCF), Leader of the Myanmar Development Committee (MDC) LAST ADDRESS: Rangoon 2014: May 5 2013: May 23 August 2 PHOTO ARREST DATE: December 11 June 4 2014 DATE: 2007: August 25 April 22 March22 March 8 2014: May 5: Section 505(b) of the Penal Code (statements conducive to mischief) and Section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act (all charges stemming from this arrest are under these sections of law) 2013 August 2: Section 505(b) of the Penal Code and Section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act (all charges stemming from this arrest are under these sections of law) SECTION OF LAW: December 11: Detained under Section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act 2012 December 17: Indicted under Section 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act 2008 November 17: Section 505(b), 124 (misprision of treason), and 143 (participation in an unlawful assembly) of the Penal Code 2014 June 4: 3 months, Section 18, Kyautada District Court June 23: 6 months, Section 505(b), South Okkalapa Township Court July 9: 3 months, Section 18, Bahan Township Court July 21: 1 year, Section 505(b), East Dagon Myo Thit Township Court; 1 year, Section 505(b), North Dagon Myo Thit Township Court August 1: 1 year, Section 505(b), Southern -

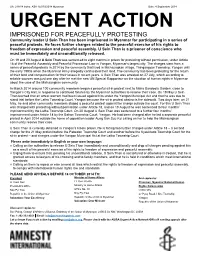

URGENT ACTION IMPRISONED for PEACEFULLY PROTESTING Community Leader U Sein Than Has Been Imprisoned in Myanmar for Participating in a Series of Peaceful Protests

UA: 218/14 Index: ASA 16/019/2014 Myanmar Date: 4 September 2014 URGENT ACTION IMPRISONED FOR PEACEFULLY PROTESTING Community leader U Sein Than has been imprisoned in Myanmar for participating in a series of peaceful protests. He faces further charges related to the peaceful exercise of his rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. U Sein Than is a prisoner of conscience who must be immediately and unconditionally released. On 19 and 20 August U Sein Than was sentenced to eight months in prison for protesting without permission, under Article 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city. The charges stem from a series of peaceful protests in 2014 by the community that lived in Michaungkan village, Thingangyun Township, Yangon until the early 1990s when the Myanmar Army allegedly confiscated their land. The community has been protesting for the return of their land and compensation for their losses in recent years. U Sein Than was arrested on 27 July, which according to reliable sources was just one day after he met the new UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar about the case of the Michaungkan community. In March 2014 around 100 community members began a peaceful sit-in protest next to Maha Bandoola Garden, close to Yangon’s City Hall, in response to continued failures by the Myanmar authorities to resolve their case. On 19 May U Sein Than learned that an arrest warrant had been issued against him under the Yangon Municipal Act and that he was due to stand trial before the Latha Township Court, Yangon because the sit-in protest obstructs the sidewalk. -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 Amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP Renewing Restrictive Measures Against Burma/Myanmar

L 210/38 EN Official Journal of the European Union 14.8.2009 III (Acts adopted under the EU Treaty) ACTS ADOPTED UNDER TITLE V OF THE EU TREATY COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (5) Moreover, the Council considers it necessary to amend the lists of persons and entities subject to the restrictive Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in measures in order to extend the assets freeze to enter particular Article 15 thereof, prises that are owned or controlled by members of the regime in Burma/Myanmar or by persons or entities associated with them, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (1) On 27 April 2006, the Council adopted Common Article 1 Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar ( 1). Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP shall be replaced by the texts of Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (2) Council Common Position 2009/351/CFSP ( 2) of 27 April 2009 extended until 30 April 2010 the Article 2 restrictive measures imposed by Common Position 2006/318/CFSP. This Common Position shall take effect on the date of its adoption. (3) On 11 August 2009, the European Union condemned Article 3 the verdict against Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and This Common Position shall be published in the Official Journal announced that it will respond with additional targeted of the European Union. restrictive measures. -

Assessment of Cultural Heritages in Yangon City Ohnmar Moe1, Ni Ni Khaing2, May Htar Lwin3 Abstract

52 Dagon University Research Journal 2020, Vol. 11 Assessment of Cultural Heritages in Yangon City Ohnmar Moe1, Ni Ni Khaing2, May Htar Lwin3 Abstract Cultural Heritage is one of Heritages and it is attractive for visitors. The aim is to understand the value of cultural heritage and assess the importance for socio-economic development of our country. Yangon is the attractive city of Myanmar and the center of economics, religion, politics and culture. According to Yangon City Heritage List of Yangon City Development Committee, it consists of 171 structures and is largely made up of mostly religious structures, and British colonial era buildings. The study is presented by the spatial distribution pattern of heritages within Yangon City, which is analysed into eight groups from the geographic point of view. The total number of heritage in city is 171, and 89 or 52 percent of them are cultural heritages. Most of the heritages are found in Kyauktada township with 39 or 23 percent. This research intends to safeguard the cultural heritage of our country to learn and to promote the cultural heritage sectors, and to help the economic growth in the area. Keywords: Cultural Heritage, religious, tourists’ attraction and economic Introduction Nowadays, many countries are trying to promote their heritage sector for their economics and raise the income of their countries by doing systematically. Yangon is Myanmar’s most popular and most important commercial center. It is located between and orth atitudes and and East ongitudes. shown in figure It is nown for the highest number of colonial period buildings in Southeast Asia.