Money Monster (Detailed Summary Not Enticing Review)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beach Theater Weekly Showtimes

Movies starting Friday, May 27 www.FMBTheater.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “X-Men: Apocalypse” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:30 Starring Jennifer Lawrence, James McAvoy and Michael Fassbender. Start 2:15 5:30 8:45 End 4:45 8:00 11:15 Rated PG-13 for sequences of violence, action and destruction, brief strong language and some suggestive material. “The Angry Birds Movie” Rated PG Run Time 1:35 Starring (voices) Bill Hader, Jason Sudeikis and Peter Dinklage Start 3:00 5:15 7:45 End 4:35 6:50 9:20 Rated PG for rude humor and action. “Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising” Rated R Run Time 1:35 Starring Seth Rogen, Zac Efron and Chloe Grace Moretz Start 2:30 4:45 7:00 9:15 End 4:05 6:20 8:35 10:50 Rated R for crude sexual content including brief graphic nudity, language throughout, drug use and teen partying. “Money Monster” Rated R Run Time 1:40 Starring Julia Roberts and George Clooney Start 3:30 6:00 8:30 End 5:10 7:40 10:10 Rated R for language throughout, some sexuality and brief violence. *** Prices *** Matinees* $9.50 (3D 12:50) Children under 12 $9.50 (3D $12.50) Seniors $9.50 (3D $12.50) ~ Adults $12.00 (3D $15.00) facebook.com/BeachTheater X-Men: Apocalypse (PG-13) • Jennifer Lawrence • James McAvoy • Michael Fassbender • Since the dawn of civilization, he was worshipped as a god. Apocalypse, the first and most powerful mutant from Marvel’s X-Men universe, amassed the powers of many other mutants, becoming immortal and invincible. -

Five Lessons the New George Clooney Movie Money Monster Teaches Us About Crisis Communications

Crisis comms to the extreme: Lee Gates' (George Clooney) life depends on what Diane Lester (Caitriona Balfe) says in this live cross Sep 09, 2016 09:16 +08 Five lessons the new George Clooney movie Money Monster teaches us about crisis communications There's a particularly tense scene in the new George Clooney movie "Money Monster", which should be of great interest to media spokespeople who are confronted with a crisis situation. Clooney, playing fictional financial TV host Lee Gates (here's lookin' at you, Jim Cramer) is threatened live on air by a gunman, who lost his life savings investing in troubled Ibis Clear Capital after it announced a big loss. Gates had recommended the algotrading company's stock on his show. Gates' down-the-line guest, Ibis' Chief Communications Officer Diane Lester (Caitriona Balfe), delivers rehearsed holding statements to the camera in a live cross. The gunman doesn't buy it, putting Gates' life perilously in danger. Gates' producer Patty Fenn (Julia Roberts), commenting in Gates' earpiece from the TV control room, doesn't buy it either. The dialogue goes something like this (spoiler alert!): Gates (to camera): We're going to talk to Diane Lester, she's the PR lady… Fenn (in his earpiece): She's the CCO. Gates: …the Chief Communications Officer at Ibis. Diane? Lester (to camera): First, let me start off by saying on behalf of everyone here at Ibis, we are prepared to do whatever we can to get you to put down that gun, Mr Budwell. Now, I understand that you have offered to compensate him for his losses personally, Lee? Well, we are absolutely willing to do the same if it helps to put an end to all this. -

ALEXANDRA CUERDO Filmmaker Working Locally in NY and LA UCLA Film 2011 | Cum Laude [email protected] | 714.746.1351 RESUME

ALEXANDRA CUERDO Filmmaker working locally in NY and LA UCLA Film 2011 | Cum laude [email protected] | 714.746.1351 RESUME Video Producer BUZZFEED | Sept 2017 - Present Produces, directs and edits viral video content for BuzzFeed. Produced the #1 most shared video on beauty brand Top Knot for September, October and November. Videos have achieved 100 million+ views and 1 million+ shares on Facebook. Director/Producer ULAM: MAIN DISH | Sept 2015 - Oct 2017 Creator of a feature-length documentary about Filipino food. Hosted by Jonathan Gold and the Los Angeles Times’ Food Bowl, the sold-out preview garnered articles in Vogue, TimeOut, Eater LA and the film is currently listed by MSN as one of the “Top 5 Food Documentaries to Watch” now. Producers’ Assistant ROUGH NIGHT | SONY PICTURES | Sept - Nov 2016 Assistant to executive producer Matt Hirsch and producer Matt Tolmach on Sony feature film in NY, starring Scarlett Johansson, Zoe Kravitz, Ilana Glazer and Kate McKinnon. Assistant Director THE PRICE | ORION PICTURES | Sept 2015, Jan - Feb 2016 Second assistant director on SXSW-premiering feature film, shot in LA and NY starring Sense8’s Aml Ameen. Production Manager THE IRON MAN EXPERIENCE | WALT DISNEY IMAGINEERING & MARVEL STUDIOS | June - Aug 2015 Managed all visual effects and live action shoots for the main Iron Man attraction in Disneyland Hong Kong. Producers’ Assistant CANNES FILM FESTIVAL | ROB HEYDON | May 2015 Assistant for the Cannes Film Festival in France. Cast Assistant - 1st MONEY MONSTER | SONY PICTURES | Feb - May 2015 Team Assistant to George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Jack O’Connell on Sony feature film in NY, dir. -

Crain's New York Business

CRAINS 20160523-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 5/20/2016 8:42 PM Page 1 CRAINS ® MAY 23-29, 2016 | PRICE $3.00 NEW YORK BUSINESS VOL. XXXII, NO. 21 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM 0 71486 01068 5 21 NEWSPAPER WE’RE IN. CBRE is honored to take home a historic 34th win ingenious. in the Real Estate Board of New York’s Most Ingenious Deal of the Year Awards. Lauren Crowley Corrinet, Gregory Tosko and Sacha innovative. Zarba received the 2015 Robert T. Lawrence Memorial Award for helping our client, LinkedIn, expand at The Empire State Building— inspiring. inspiring an icon to innovate for one of tech’s most innovative companies. We’re proud of our creative partnership with LinkedIn— and the advantage we bring to the tech sector in its growth across New York City. 20160523-NEWS--0003-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 5/20/2016 8:33 PM Page 1 MAYCRAINS 23-29, 2016 FROM THE NEWSROOM | JEREMY SMERD Interesting conflicts IN THIS ISSUE 4 AGENDA THE MOST RECENT DUSTUP 5 IN CASE YOU MISSED IT between Gov. Andrew Cuomo and No good subway Mayor Bill de Blasio, this time over the development of two 6 ASKED & ANSWERED improvement goes unpunished residential buildings at Pier 6 in Brooklyn Bridge Park, says 7 TRANSPORTATION a lot about their attitudes toward the incestuous way 8 WHO OWNS THE BLOCK politics and business commingle in New York. 9 INFRASTRUCTURE The mayor wants to push his agenda in the face of 10 questions about quid pro quos for campaign donors, while VIEWPOINTS the governor, facing similar questions, is more than happy to shine a spotlight on the FEATURES mayor as several probes by U.S. -

For Your Consideration – Crystal Ball Edition

Issue 118 May 2015 A NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY For Your Consideration – Crystal Ball Edition Ji m K e l l e r The early part of the Oscar race is a moving how they affected his family life and pos- my most anticipated films of the year. Eg- target. There are a few awards stops along sibly his health. Michael Fassbender plays gers won the Directing Award in the U.S. the way: Sundance, SXSW, and Cannes, Jobs and could figure prominently in the Dramatic category at this year’s Sundance to name a few, but by and large spitballing Best Actor race. Film Festival. what may come down the slippery slope of Why I’ve got my eye on it: Like Hoop- the Oscar pike is tricky. For one, a lot of the er, Boyle is permanently on the Academy Macbeth (director: Justin Kurzel): films do not have distributors yet or have watch list ever since his go for broke Slum- Why you might like it: Michael Fass- soft release dates. This makes it easy for dog Millionaire swept the 2009 Oscars and bender stars in this drama, based on Wil- films to be pushed to the following year. won eight awards including Best Picture liam Shakespeare’s play of the same name, Second, the films discussed here haven’t and Best Director. Here he is paired with as the ill-fated duke of Scotland who re- screened, so it’s really impossible to know Aaron Sorkin, an Oscar perennial since his ceives a prophecy from three witches that what kind of film they are—all we have to 2011 Best Adapted Screenplay win for The he will become King. -

Production Information Four-Time Oscar®-Winning Filmmakers

Production Information Four-time Oscar®-winning filmmakers JOEL COEN & ETHAN COEN (No Country for Old Men, True Grit, Fargo) write and direct Hail, Caesar!, an all-star comedy fueled by a brilliant cast led by JOSH BROLIN (No Country for Old Men), Oscar® winner GEORGE CLOONEY (Gravity), ALDEN EHRENREICH (Blue Jasmine), RALPH FIENNES (The Grand Budapest Hotel), JONAH HILL (The Wolf of Wall Street), SCARLETT JOHANSSON (Lucy), Oscar® winner FRANCES ® MCDORMAND (HBO’s Olive Kitteridge), Oscar winner TILDA SWINTON (Michael Clayton) and CHANNING TATUM (Magic Mike). When the world’s biggest star vanishes and his captors demand an enormous ransom for his safe return, it will take the power of Hollywood’s biggest names to solve the mystery of his disappearance. Bringing the audience along for a comic whodunit that pulls back the curtain and showcases the unexpected humor and industry drama found behind the scenes, Hail, Caesar! marks the Coens at their most inventive. Eddie Mannix’s (Brolin) job as a studio fixer begins before dawn, as he arrives just ahead of the police to keep one of Capitol Pictures’ prized starlets from being arrested on a morals charge. His work is never dull, and it is around the clock. Each film on the studio’s slate comes complete with its own headache, and Mannix is tasked with finding a solution to every one of them. He is the point man when it comes to procuring sign-off from religious leaders on an upcoming Biblical epic…as well as when disgruntled director Laurence Laurentz (Fiennes) shirks at having cowboy star Hobie Doyle (Ehrenreich) thrust upon him to appear in Capitol’s latest sophisticated drama. -

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

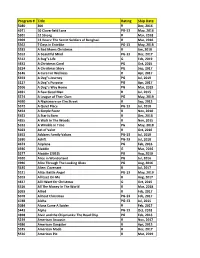

Program # Title Rating Ship Date

Program # Title Rating Ship Date 5080 300 R Dec, 2016 4971 10 Cloverfield Lane PG-13 May, 2016 5301 12 Strong R Mar, 2018 4909 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi R Mar, 2016 5362 7 Days in Entebbe PG-13 May, 2018 5283 A Bad Moms Christmas R Jan, 2018 5263 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 Dec, 2017 5512 A Bug''s Life G Feb, 2019 4832 A Christmas Carol PG Oct, 2015 5224 A Christmas Story PG Sep, 2017 5146 A Cure For Wellness R Apr, 2017 5593 A Dog''s Journey PG Jul, 2019 5127 A Dog''s Purpose PG Apr, 2017 5506 A Dog''s Way Home PG Mar, 2019 4691 A Few Good Men R Jul, 2015 5574 A League of Their Own PG May, 2019 4690 A Nightmare on Elm Street R Sep, 2015 5372 A Quiet Place PG-13 Jul, 2018 5454 A Simple Favor R Nov, 2018 5453 A Star Is Born R Dec, 2018 4855 A Walk In The Woods R Nov, 2015 5332 A Wrinkle In Time PG May, 2018 5023 Act of Valor R Oct, 2016 5392 Addams Family Values PG-13 Jul, 2018 5380 Adrift PG-13 Jul, 2018 4673 Airplane PG Feb, 2016 4936 Aladdin G Mar, 2016 5577 Aladdin (2019) PG Aug, 2019 4920 Alice in Wonderland PG Jul, 2016 4996 Alice Through The Looking Glass PG Aug, 2016 5185 Alien: Covenant R Jul, 2017 5521 Alita: Battle Angel PG-13 May, 2019 5203 All Eyez On Me R Aug, 2017 4837 All I Want for Christmas G Oct, 2015 5316 All The Money In The World R Mar, 2018 5093 Allied R Feb, 2017 5078 Almost Christmas PG-13 Feb, 2017 4788 Aloha PG-13 Jul, 2015 5084 Along Came A Spider R Feb, 2017 5443 Alpha PG-13 Oct, 2018 4898 Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip PG Feb, 2016 5239 American Assassin R Nov, 2017 4686 American Gangster -

DVD Spring 2017 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2017

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2017 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2017. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0428 is a DVD entitled “Me Before You”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not Pre-Ratings be suitable for children. -

Dr. Ed's Movie Reviews 2016

Dr. Ed’s Movie Reviews 2016 Yardeni Research, Inc. Dr. Edward Yardeni 516-972-7683 [email protected] Please visit our sites at www.yardeni.com blog.yardeni.com thinking outside the box The Accountant (+) stars Ben Affleck as a wiz accountant whose autism gives him an extraordinary ability to remember reams of numbers. So he has a great knack for forensic accounting. He also has a compulsive need to finish the complex accounting puzzles he faces, and occasionally does so with lethal force. He is the good guy. The bad guys are aiming to take their company public. Hollywood loves to take out crooked business people. How about a movie about the crooks in Washington? Arrival (+) is a sci-fi flick starring Amy Adams. She plays a language expert recruited by the army to try to communicate with tall octopus-like aliens that have mysteriously landed their spaceships in 12 countries on Earth. It’s a slow-paced movie, but raises interesting philosophical questions about our relationship to the future. It is also timely since there are many people in America and around the world who view Donald Trump’s arrival in the White House as similar to an alien invasion. The movie suggests that we should give him a chance. He might be coming in peace and make the world a better place. Anthropoid (+ + +) is an excellent movie based on the true story of “Operation Anthropoid.” That was the code name for the mission impossible that two Czech soldiers were assigned by their government-in-exile in London. -

Masterclass Scene 1 1 Int

1 INT. MASTERCLASS SCENE 1 JODIE FOSTER CHAPTER 01 MASTERCLASS Introduction1 JODIE FOSTER CHAPTER 01 Jodie Foster Biography odie Foster’s stunning performances as a rape survivor in The Accused (1988) and as Special JAgent Clarice Starling (1991) in the hit thriller The Silence of the Lambs earned her two Academy Awards for Best Actress and a reputation as one of the most critically acclaimed actresses of her generation. Jodie made her acting debut at age three, appearing as The Coppertone Girl in the sunscreen brand’s television commercials. She became a regular on several television series, including Mayberry R.F.D., The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, My Three Sons, and Paper Moon before landing her first feature film role in Napoleon and Samantha (1972)—when she was only eight years old. Following a notable role in Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1975), Jodie worked with the director again in 1976’s Taxi Driver. She won In addition to her acting, Jodie has always had a widespread critical praise, international attention, and keen interest in the art of filmmaking. She made her first Oscar nomination for her breakthrough per- her motion picture directorial debut in 1991 with the formance as a streetwise teenager in the award-win- highly-acclaimed Little Man Tate. Jodie founded her ning psychological thriller. Other select motion picture production company, Egg Pictures, in 1992; with credits include Woody Allen’s stylized black and white the company, she produced, directed, and acted in comedy Shadows and Fog (1991); Roman Polanski’s several award-winning films, including Nell (1994), comedy Carnage (2011), Neil Jordan’s The Brave for which she received an Academy Award nomina- One (2007), Spike Lee’s blockbuster bank heist tion. -

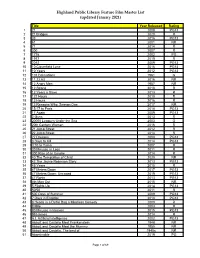

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (Updated January 2021)

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (updated January 2021) Title Year Released Rating 1 21 2008 PG13 2 21 Bridges 2020 R 3 33 2016 PG13 4 61 2001 NR 5 71 2014 R 6 300 2007 R 7 1776 2002 PG 8 1917 2019 R 9 2012 2009 PG13 10 10 Cloverfield Lane 2016 PG13 11 10 Years 2012 PG13 12 101 Dalmatians 1961 G 13 11.22.63 2016 NR 14 12 Angry Men 1957 NR 15 12 Strong 2018 R 16 12 Years a Slave 2013 R 17 127 Hours 2010 R 18 13 Hours 2016 R 19 13 Reasons Why: Season One 2017 NR 20 15:17 to Paris 2018 PG13 21 17 Again 2009 PG13 22 2 Guns 2013 R 23 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 2003 G 24 20th Century Women 2016 R 25 21 Jump Street 2012 R 26 22 Jump Street 2014 R 27 27 Dresses 2008 PG13 28 3 Days to Kill 2014 PG13 29 3:10 to Yuma 2007 R 30 30 Minutes or Less 2011 R 31 300 Rise of an Empire 2014 R 32 40 The Temptation of Christ 2020 NR 33 42 The Jackie Robinson Story 2013 PG13 34 45 Years 2015 R 35 47 Meters Down 2017 PG13 36 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 2019 PG13 37 47 Ronin 2013 PG13 38 4th Man Out 2015 NR 39 5 Flights Up 2014 PG13 40 50/50 2011 R 41 500 Days of Summer 2009 PG13 42 7 Days in Entebbe 2018 PG13 43 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag a Mindless Comedy 2000 R 44 8 Mile 2003 R 45 90 Minutes in Heaven 2015 PG13 46 99 Homes 2014 R 47 A.I.