Spring/Summer 2001 First Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healing Through Song

Innovation In Action Healing Through Song Music Therapy After-Care for Sexual Violence Survivors Panzi Foundation USA What s really important about this project is the innovative element; music therapy’ is still not often used and to pilot this kind of work especially in Congo is “ground breaking. The project goes beyond traditional techniques to treat the participants not as patients but as artists which is really empowering for the women. It highlights their dignity and reconnects them in a way that traditional talk therapy and perhaps other forms of group therapy don t achieve. Naama Haviv, Panzi Foundation USA ’ ” In the wake of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and the ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the extent of sexual violence is well documented. In May 2011, the american journal Public Health noted that over 1100 women and girls are raped every day in DRC. Increasingly, children under the age of five are subject to sexual violence and being brought into the local hospital in Panzi with horrific injuries. Using music therapy, this project is a crucial and innovative way to try to rehabilitate the survivors of this abuse, to reintegrate them back into society and to prevent ongoing abuse from taking place in the future. The messages delivered through this music can raise awareness that leads to the change necessary for future prevention. The programme will also serve as a beacon to bring more women to the hospital to receive treatment. After the first rape, my husband left me. He said I must be contaminated. -

Asthma: the Soap Opera

Asthma: The Soap Opera Angela: I'm sorry… my love. I can't. My father said no. Mario: Think of yourself. Think of us. Our love. Angela: I will think of you always. I love you. But our love can never be. Mario: Please don't do this to me. First, my wife died in a car crash. Then, our baby son got sick. And now, losing you. It's too much for me. Angela: I have no choice. I want to stay, but I cannot. Mario: When you leave, you are taking my heart. How can I live without you? Angela: I will love you always. Never forget me! (Angela leaves. Mario is crying. The doorbell rings.) Director: Cut! Cut! Cut! Mario: What? Director: The doorbell was ringing. You have to answer it. Mario: How can I answer the door? My life will never be the same. Director: Exactly. So the doorbell rings, and you answer it. Why are you over here crying by the baby? Mario: Because… The baby has asthma. He can't breathe! Director: Didn't you read the script? The story is about you and your lost love. Not the baby. Forget about the baby. Mario: Didn't I read the script? Didn't you read the script? The script says, the baby has asthma. How can I forget about my baby son? My little boy needs my help. He needs me. Director: It's just asthma. It's no big deal. ©2018 The New York City Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs 1 Mario: What do you mean no big deal? I don't think you know enough about asthma. -

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. As performed in principal recordings (or demos) by or with Gram Parsons or, in the case of Gram Parsons compositions, performed by others. Gram often varied, adapted or altered the lyrics to non-Parsons compositions; those listed here are as sung by him. Gram’s birth name was Ingram Cecil Connor III. However, ‘Gram Parsons’ is used throughout this document. Following his father’s suicide, Gram’s mother Avis subsequently married Robert Parsons, whose surname Gram adopted. Born Ingram Cecil Connor III, 5th November 1946 - 19th September 1973 and credited as being the founder of modern ‘country-rock’, Gram Parsons was hugely influenced by The Everly Brothers and included a number of their songs in his live and recorded repertoire – most famously ‘Love Hurts’, a truly wonderful rendition with a young Emmylou Harris. He also recorded ‘Brand New Heartache’ and ‘Sleepless Nights’ – also the title of a posthumous album – and very early, in 1967, ‘When Will I Be Loved’. Many would attest that ‘country-rock’ kicked off with The Everly Brothers, and in the late sixties the album Roots was a key and acknowledged influence, but that is not to deny Parsons huge role in developing it. Gram Parsons is best known for his work within the country genre but he also mixed blues, folk, and rock to create what he called “Cosmic American Music”. While he was alive, Gram Parsons was a cult figure that never sold many records but influenced countless fellow musicians, from the Rolling Stones to The Byrds. -

Ani Kolangian

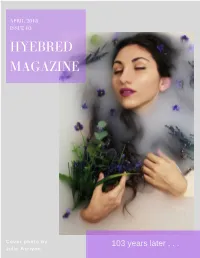

APRIL 2018 ISSUE 03 HYEBRED MAGAZINE Cover photo by 103 years later . Julie Asriyan Forget-Me-Not Issue 03 Prose Music Anaïs Chagankerian . 6 Brenna Sahatjian . 13 Lizzie Vartanian Collier . 20 Ani Kalayjian . 34 Armen Bacon . .38 Mary Kouyoumdjian . 36 Poetry Art & Photography Ani Chivchyan . 3 Julie Asriyan . 10 Ronald Dzerigian . 14 Ani Iskandaryan . 18 Nora Boghossian . .16 Susan Kricorian . 28 Rita Tanya . .31 Ani Kolangian . .32 John Danho . .49 Nicole Burmeister . .52 A NOTE OF GRATITUDE Dear Faithful Reader, This issue is dedicated to our Armenian ancestors. May their stories never cease to be told or forgotten. As April is Genocide Awareness Month, the theme for this issue is fittingly 'Forget-Me-Not.' It has been 103 years since the Armenian Genocide, a time in Armenian history that still hurts and haunts. HyeBred Magazine represents the vitality and success of the Armenian people; it showcases how far we have come. Thank you to our wonderfully talented contributors. Your enthusiastic collaboration enhances each successive publication. Thank you, faithful reader, as your support is what keeps this magazine alive and well. Շնորհակալություն. The HyeBred Team Ani Chi vchyan Self Love don't let yourself get in the way of yourself the same way you can harm yourself, adding salt to those wounds and grow only in sorrow and grief only to become tired of yourself you have the power to heal and love admire celebrate your existence in this world water those roots and make something beautiful out of you H Y E B R E D I S S U E 0 3 | 3 By -

GRASS IS GROWING in the EAST for the Taiwanese Poet Yu Hsi

GRASS IS GROWING IN THE EAST for the Taiwanese poet Yu Hsi Grass, growing in the east in yellow waves, and kneeling and bowing for so long to the exalted east. I place my aching head upon its warm breast. It strokes my brow with its yellowing fingers, my tears falling thicker and thicker, covering the silksoft lichen. An inner suffering rides upon waves into the east, marking my warm body, and grasshoppers flock into the silent aeons, dispersing the light at the final moment of rest… And for some time yet to come, its face unchanging in golden waves, there will be grass, growing in the east. Bankok BEAUTY, DOZING To touch the silvern collar of the beauty, dozing, was my eternal desire, and my own silver verses lit the way like a candle. My own dear love herself had fashioned the portentous evening moon, and, moved by the moment, I offered a joyful candle, an ancient prayer, to the Buddha, while silence filled the spaces between joyful leaves. But still more desires pain the shameless vagrant… I touch the silvern neck of the beauty, dozing, but my eternal desire stays unfulfilled. I touch her lips… THE SKYBLUE OCEAN (from The Book of India) How can I forget your skyblue ocean? How can I forget the silent and beauteous Buddha? How can I forget the eyes of melancholy stones? How can I forget the unshod Tamils? How can I forget a temple with a golden roof? How can I forget the love of small children, holding out their hands? How can I forget the girls with their callouses and shining eyes? How can I forget sneaking a look at their naked breasts? -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

The Imitation of Christ

The Catholic Primer’s Reference Series: THE IMITATION OF CHRIST THOMAS À KEMPIS Caution regarding printing: This document is over 117 pages in length, depending upon individual printer settings. PLEASE NOTE: The original source of this document is in the public domain. The Catholic Primer Copyright Notice The contents The Imitation of Christ by Thomas A Kempis is in the public domain. However, this electronic version is copyrighted. © The Catholic Primer, 2004. All Rights Reserved. This electronic version may be distributed free of charge provided that the contents are not altered and this copyright notice is included with the distributed copy, provided that the following conditions are adhered to. This electronic document may not be offered in connection with any other document, product, promotion or other item that is sold, exchange for compensation of any type or manner, or used as a gift for contributions, including charitable contributions without the express consent of The Catholic Primer. Notwithstanding the preceding, if this product is transferred on CD-ROM, DVD, or other similar storage media, the transferor may charge for the cost of the media, reasonable shipping expenses, and may request, but not demand, an additional donation not to exceed US$15. Questions concerning this limited license should be directed to [email protected] . This document may not be distributed in print form without the prior consent of The Catholic Primer. Adobe®, Acrobat®, and Acrobat® Reader® are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. The Catholic Primer: www.catholicprimer.org THE IMITATION OF CHRIST BY THOMAS À KEMPIS TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN INTO MODERN ENGLISH FOREWORD IN PREPARING this edition of The Imitation of Christ, the aim was to achieve a simple, readable text which would ring true to those who are already lovers of this incomparable book and would attract others to it. -

Angela Mario Director Senior Young Maria Nurse Doctor Young Man Boy Woman

Angela Mario Director Senior Young Maria Nurse Doctor Young Man Boy Woman English Arabic أﻧﺠﻴﻼ ANGELA أﻧﺎ ﺁﺳﻔﺔ، ﻳﺎ ﺣﺒﻴﺒﻲ. ﻻ أﺳﺘﻄﻴﻊ. .I’m sorry, my love. I can't ﻓﻘﺪ رﻓﺾ أﺑﻲ هﺬا اﻟﺰواج. .My father said no ﻣﺎرﻳﻮ MARIO ﻓﻜّﺮي ﻓﻲ ﻧﻔﺴﻚ. .Think of yourself ﻓﻜّﺮي ﻓﻴﻨﺎ. .Think of us ﺣﺒﻨﺎ. .Our love أﻧﺠﻴﻼ ANGELA ﺳﻮف أﻓﻜﺮ ﻓﻴﻚ د ا ﺋ ﻤ ﺎً. .I will think of you always أﺣﺒﻚ. .I love you وﻟﻜﻦ ﺣﺒﻨﺎ ... ﻻ ﻳﻤﻜﻦ أن ﻳﺴﺘﻤﺮ. .But our love can … never be ﻣﺎرﻳﻮ MARIO [ﺗﻨﻬﺪات] [sobs] أ ر ﺟ ﻮ كِ ﻻ ﺗﻔﻌﻠﻲ هﺬا ﺑﻲ. .Please don't do this to me ﻓﻲ اﻟﺒﺪاﻳﺔ ﻣﺎﺗﺖ زوﺟﺘﻲ ﻓﻲ ﺣﺎدث ﺳﻴﺎرة. .First, my wife died in a car crash ﺛﻢ ﻣَﺮِض اﺑﻨﻨﺎ اﻟﺼﻐﻴﺮ. .Then, our baby son got sick واﻵن ... أﻓﻘﺪك. آﻞ ذﻟﻚ ﻓﻮق اﺣﺘﻤﺎﻟﻲ. .And now ... losing you. It's too much for me أﻧﺠﻴﻼ ANGELA ﻟﻴﺲ ﻟ ﺪ يّ اﺧﺘﻴﺎر. .I have no choice أ و دّ أن أﺑﻘﻰ وﻟﻜﻨﻨﻲ ﻻ أﺳﺘﻄﻴﻊ. .I want to stay, but I cannot ﻣﺎرﻳﻮ MARIO ﻋﻨﺪﻣﺎ ﺗﺘﺮآﻴﻨﻲ، ﻓﺈﻧﻚ ﺗﺄﺧﺬﻳﻦ ﻗﻠﺒﻲ ﻣﻌﻚ. .When you leave, you are taking my heart آﻴﻒ أﺳﺘﻄﻴﻊ أن أﻋﻴﺶ ﺑﺪوﻧﻚ؟ ?How can I live without you أﻧﺠﻴﻼ ANGELA ﺳﺄﺣﺒﻚ د ا ﺋ ﻤ ﺎً. .I will love you always ﻻ ﺗﻨﺴﺎﻧﻲ أ ﺑ ﺪ اً! !Never forget me ﻣﺎرﻳﻮ MARIO [ﺑﻜﺎء، ﺗﻨﻬﺪات] [cries, sobs] اﻟﻄﻔﻞ BABY [ﺑﻜﺎء] [crying] اﻟﻤﺨﺮج DIRECTOR ﺗﻮﻗﻒ! !Cut ﺗﻮﻗﻒ! !Cut ﺗﻮﻗﻒ! !Cut We Are New York: Asthma: The Soap Opera 1 Mario Director ﻣﺎرﻳﻮ MARIO ﻣﺎذا؟ ?What اﻟﻤﺨﺮج DIRECTOR ﺟﺮس اﻟﺒﺎب آﺎن ﻳ ﺮ نّ. -

Little Bird Little Bird I Want to Sing a Song For

Little bird Little bird I want to sing a song for you ‘cause you were a witness of a love so new You were sitting there singing your happy tune We were sitting there looking at you Let me ask you something , oh my little one Did you notice how he made me blush? If you did then tell me could he be the one Even though it started with a crush Little bird, i can’t speak to you But I wonder if you’d only knew That I’m still lying in his arms each night And sometimes we think of you Maybe it didn’t mean a lot to you We were just two people in the night Even though we noticed a little bird like you You were sitting ,waiting for the first sunlight Little bird I want to sing a song for you ‘Cause you were a witness of a love so true You were sitting there singing your happy tune We were sitting there looking at you Anything for you Thinking of you all the time Loving you is on my mind And I think that you’re my guy ‘cause when you’re touching me I sigh When you look at me and smile I’m warming up and in a while Loving you is all I want to do I don’t know what it is, I have no clue But if you want me to ,I would do Anything for you, I would do anything for you Ooh I would do Anything for you, I would do anything for you Your funny ways your tenderness Without all that, sure I’m a mess You make me wanna sing out loud My heart is happy and wants to keep you proud But if you want me to ,I would do Anything for you, I would do anything for you Ooh I would do Anything for you, I would do anything for you Good old sunday blues Dancing, swinging, having -

Marvin Gaye Volume Two 1966 - 1970 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marvin Gaye Volume Two 1966 - 1970 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Volume Two 1966 - 1970 Country: UK & Europe Released: 2016 Style: Soul, Vocal, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1234 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1627 mb WMA version RAR size: 1642 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 321 Other Formats: RA MP2 AHX VOC AA MPC AUD Tracklist Moods Of Marvin Gaye 1-1 –Marvin Gaye I'll Be Doggone 1-2 –Marvin Gaye Little Darling (I Need You) 1-3 –Marvin Gaye Take This Heart Of Mine 1-4 –Marvin Gaye Hey Diddle Diddle 1-5 –Marvin Gaye One More Heartache 1-6 –Marvin Gaye Ain't That Peculiar 1-7 –Marvin Gaye Night Life 1-8 –Marvin Gaye You've Been A Long Time Coming 1-9 –Marvin Gaye Your Unchanging Love 1-10 –Marvin Gaye You're The One For Me 1-11 –Marvin Gaye I Worry 'Bout You 1-12 –Marvin Gaye One For My Baby (And One More For The Road) Take Two 2-1 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston It Takes Two 2-2 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston I Love You, Yes I Do 2-3 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Baby I Need Your Loving 2-4 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston It's Got To Be A Miracle (This Thing Called Love) 2-5 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Baby Say Yes 2-6 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston What Good Am I Without You 2-7 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Till There Was You 2-8 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Love Fell On Me 2-9 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Secret Love 2-10 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston I Want You 'Round 2-11 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston Heaven Sent You I Know 2-12 –Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston When We're Together United 3-1 –Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3-2 -

Veritas 102 V2 ENG Copy.Jpg

From Our Pastor’s Desk by Fr. Roberto Corral, O.P. Lenten Preaching Series: Unbound – Freedom in Christ I am offering a preaching series entitled “Unbound – Freedom In Christ” during the first five weekends of Lent. It is based on a worldwide ministry headed by a Catholic couple named Neal and Janet Lozano for over thirty years, and its purpose is to help us Christians attain the freedom God gives us in Jesus: freedom from the lies, darkness and snares the devil wishes to use to keep us bound. Many of us can be burdened and bound by sin, guilt, shame, past abuse or hurts caused by others, addictions, anger, bitterness, lack of forgiveness, etc. This is what traditional Catholic theology calls spiritual bondage. One of the goals of our life of faith, and the focus of the Unbound Model of ministry is to free us from this spiritual bondage. As Neal Lozano says in one of his books: “Picture a locked door. Opening that door represents liberation from spiritual bondage. This door has five locks, each requiring a key. As a believer in Christ, you have all the keys you need to be free from the influence of evil spirits. If one key has not been used the bolt remains in place and the door will not move. It may be nice knowing that you have used four keys, but it will not get you through the door to liberation” (Unbound: A Practical Guide to Deliverance, p. 56, Chosen Books, Grand Rapids, MI). The Unbound ministry, and my preaching series, will focus on what the Lozanos call the Five Keys referred to in the quote above: 1. -

Roptc L\Tbtrit~

~roptc l\tbtrit~ BY UN A 1\1. MARSON. I• ~ ~ ~ ..._.,~.~.. ~_. ... General Register Office, Spanish Town, amaica, .. cQblt~. T' .1930,. Delivered to the Registrar-G era} nder the provision~ of Section 3 of Law 2 0 1887, entitled "A Law to provide for the preservation of copies of Books printed in Jamaica, and f~ Registra tion of such Books." PREFACE, PRESENT this little.... book of poemB to thole of the public who care to read it, without apology. Some of the poelIl8 included have al ready been published in the local "Cosmopolitan" Magazine, and others in the local newBpapers, Of their worth it is not for me to apeak, except to say that they are the 'heart-throba' of one who from earliest childhood has worshipped at the 8brine of the muses and dwelt among the open spaces and the silent hills where the CAldenceti of Nature's voice tempt ODe to answering Bong, I have been encouraged to present these poems in book-form by many who have read snatches of my writings, and if in so doing I givp. pleasure to them I shall be amply rewarded. v. PREFACE To thoRp. who refill thrm for thp. first tim!', I tl'lIRt thrir' Rincerity will nppral in AllCh a "':1y :1S til ('OmpplIRatfl for :1l1,V of thoRr fllultR which :1 rr fHl I'r:1'1 i I." t () I1fl clptpctrd in IIH' workR of a np.w :1lld hlllllbll' :1RJlir':1nt to a pl:1cP :1rnoll~ thp Singe.rs "WhIlR!' sOllgR ~lIRhrd from their hrartR", UNA M.