"Blockbuster Sermons" and Authorship Issues in Evangelicalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Harmony of the Life of Paul

A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul A Chronological Study Harmonizing The Book Of Acts With Paul’s Epistles This material is from ExecutableOutlines.com, a web site containing sermon outlines and Bible studies by Mark A. Copeland. Visit the web site to browse or download additional material for church or personal use. The outlines were developed in the course of my ministry as a preacher of the gospel. Feel free to use them as they are, or adapt them to suit your own personal style. To God Be The Glory! Executable Outlines, Copyright © Mark A. Copeland, 2007 Mark A. Copeland A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul Table Of Contents Paul's Life Prior To Conversion 3 The Conversion Of Paul (36 A.D.) 6 Paul’s Early Years Of Service (36-45 A.D.) 10 First Missionary Journey, And Residence In Antioch (45-49 A.D.) 13 Conference In Jerusalem, And Return To Antioch (50 A.D.) 17 Second Missionary Journey (51-54 A.D.) 20 Third Missionary Journey (54-58 A.D.) 25 Arrest In Jerusalem (58 A.D.) 30 Imprisonment In Caesarea (58-60 A.D.) 33 The Voyage To Rome (60-61 A.D.) 37 First Roman Captivity (61-63 A.D.) 41 Between The First And Second Roman Captivity (63-67 A.D.) 45 The Second Roman Captivity (68 A.D.) 48 A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul 2 Mark A. Copeland A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul Paul's Life Prior To Conversion INTRODUCTION 1. One cannot deny the powerful impact the apostle Paul had on the growth and development of the early church.. -

Preparation for Water Baptism Pastor E

Preparation for Water Baptism Pastor E. Keith Hassell 1. The Purpose Water baptism is the first step in obedience to Christ. In the New Testament, there were no “altar calls” as we know them today. The message was clear: “If you want to give your life to Jesus and follow Him, come to the water and be baptized!” There is no biblical pattern for salvation apart from baptism. Water baptism finds it’s meaning in spiritual symbolism. Water baptism by immersion is the first step of obedience to Christ but is also a public witness of our faith through identification with the death, burial, and resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ. When we enter the baptismal waters, we enter in response to our need to be cleansed and saved from sin. It is in baptism that we make public confession of Jesus Christ as our personal Lord and Savior and acknowledge our belief in the death, burial and resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ (Romans 10:9-10). When we are immersed under the baptismal waters, we identify with the death and burial of the Lord Jesus Christ. In doing so, we also symbolize and submit to our own death and departure from our old life of sin. When we rise from the water, we identify with the resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ and demonstrate our commitment to walk in a newness of life in Christ apart from sin. ROMANS 6:4,5 (NKJV) Therefore we were buried with Him through baptism into death, that just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life, For if we have been united together in the likeness of His death, certainly we also shall be in the likeness of His resurrection. -

How Was the Sermon? Mystery Is That the Spirit Blows Where It Wills and with Peculiar Results

C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL S FORUMEMINARY The Sermon 1. BIBLICAL • The sermon content was derived from Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon helped you understand the text better: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon revealed how God is at work in the text: 1 2 3 4 5 How Was the• The sermonSermon? displayed the grace of God in Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 1=Excellent 2=Very Good 3=Good 4=Average 5=Poor W INTER 2008 C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL SEMINARY from the president FORUM Cornelius Plantinga, Jr. Providing Theological Leadership for the Church Volume 15, Number 1 Winter 2008 Dear Brothers and Sisters, REFLECTIONS ON Every Sunday they do it again: thousands of ministers stand before listeners PREACHING AND EVALUATION and preach a sermon to them. If the sermon works—if it “takes”—a primary cause will be the secret ministry of the Holy Spirit, moving mysteriously through 3 a congregation and inspiring Scripture all over again as it’s preached. Part of the How Was the Sermon? mystery is that the Spirit blows where it wills and with peculiar results. As every by Scott Hoezee preacher knows, a nicely crafted sermon sometimes falls flat. People listen to it 6 with mild interest, and then they go home. On other Sundays a preacher will Good Preaching Takes Good Elders! walk to the pulpit with a sermon that has been only roughly framed up in his by Howard Vanderwell (or her) mind. The preacher has been busy all week with weddings, funerals, and youth retreats, and on Sunday morning he isn’t ready to preach. -

The Pastor: Forming a Shared Vocational Vision

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Christian Ministry 3-2014 The aP stor: Forming a Shared Vocational Vision Skip Bell Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/christian-ministry-pubs Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Skip, "The asP tor: Forming a Shared Vocational Vision" (2014). Faculty Publications. Paper 34. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/christian-ministry-pubs/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christian Ministry at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SKIP BELL Skip Bell, DMin, is professor of Christian leadership and director of the Doctor of Ministry program, Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, United States. The pastor: Forming a shared vocational vision ho defines the voca- do it if they are to be effective in their biblical dimensions of discipleship tional vision for ministry or leadership. often retreat to the background. pastoral ministry? Is it How does a pastor arrive at the right Church organizational leaders and Wthe employing denomi- mental image regarding a biblical vision seminary professors share the same nation? Is it the congregation the pastor for ministry? The answer is complicated. responsibility, to reflect on a biblical serves? Is it the church board? Is it the To be sure, a pastor has prayed over vision for pastoral ministry. Church demand of the moment—preaching, a sense of calling and struggled with organizations form internships, field evangelism, mission, church planting? his or her vocational decision. -

Lesson Outline I the Scriptural Church Officers A. Pastor B

ABCs of Mature Christianity Lesson 17 – Qualifications for Officers 6-5-2016 Lesson Outline P. He Must Be of GOOD I The Scriptural Church Officers REPORT: A. Pastor Q. He Must NOT Be Self-willed: B. Deacon R. He Must a LOVER of Good Men: S. He Must Be JUST: II The Qualifications of a Pastor T. He Must Be HOLY: A. He Must Be BLAMELESS: U. He Must Be TEMPERATE: B. He Must Be HUSBAND OF ONE V. He Must Be SOUND IN WIFE: DOCTRINE: C. He Must Be VIGILANT: D. He Must Be SOBER: III The Qualifications of a Deacon E. He Must Be OF GOOD A. Qualifications in Common BEHAVIOR: with a Bishop: F. He Must Be GIVEN TO B. Other Qualifications: HOSPITALITY: C. The Qualifications of the G. He Must Be APT TO TEACH: Wife of a Deacon H. He Must Be NOT BE GIVEN TO WINE: IV Disqualification from Office I. He Must NOT Be A STRIKER: A. High Standards Must Be J. He Must NOT Be GIVEN TO Set: FILTY LUCRE: K. He Must Be PATIENT: B. Great Care Must Be L. He Must NOT Be a Brawler: Exercised: M. He Must NOT Be Covetous: C. With Responsibility Comes N. He Must Be: One that ruleth Accountability well his own house. O. He Must Not Be a NOVICE: WBC Robert J. Sargent Page 1 of 53 ABCs of Mature Christianity Lesson 17 – Qualifications for Officers 6-5-2016 Qualifications of Officers This study considers the qualifications set forth in scriptures and required of a man who serves as an officer in a church. -

The Healing Ministry of Jesus As Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-2006 The eH aling Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels Alvin Lloyd Maragh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Medical Humanities Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Maragh, Alvin Lloyd, "The eH aling Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels" (2006). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 457. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/457 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LOMA LINDA, CALIFORNIA LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Faculty of Religion in conjunction with the Faculty of Graduate Studies The Healing Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels by Alvin Lloyd Maragh A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Clinical Ministry June 2006 CO 2006 Alvin Lloyd Maragh All Rights Reserved Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in his opinion is adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree Master of Arts. Chairperson Siroj Sorajjakool, Ph.D7,-PrOfessor of Religion Johnny Ramirez-Johnson, Ed.D., Professor of Religion David Taylor, D.Min., Profetr of Religion 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank God for giving me the strength to complete this thesis. -

Heart of Anglicanism Week #1

THE HEART OF ANGLICANISM #1 What Exactly Is an Anglican? Rev. Carl B. Smith II, Ph.D. WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE ANGLICAN? ANGLICANISM IS… HISTORICAL IN ORIGIN • First Century Origin: Christ and Apostles (Apostolic) • Claims to Apostolicity (1st Century): RCC & Orthodox • Protestants → through RCC (end up being anti-RCC) • Church of England – Anglican Uniqueness • Tradition – Joseph of Arimathea; Roman Soldiers; Celtic Church; Augustine of Canterbury; Synod of Whitby (664), Separated from Rome by Henry VIII (1534; Reformation) • A Fourth Branch of Christianity? BRANCHES OF CHRISTIAN CHURCH GENERALLY UNIFIED UNTIL SCHISM OF 1054 Eastern Church: Orthodox Western Church: Catholic Patriarch of Constantinople Reformation Divisions (1517) • Greek Orthodox 1. Roman Catholic Church • Russian Orthodox 2. Protestant Churches • Coptic Church 3. Church of England/ • American Orthodox Anglican Communion (Vatican II Document) NAME CHANGES THROUGH TIME • Roman Catholic until Reformation (1534) • Church of England until Revolutionary War (1785) • In America: The (Protestant) Episcopal Church • Break 2009: Anglican Church in North America • Founded as province of global Anglican Communion • Recognized by Primates of Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans (African, Asian, So. American) TWO PRIMARY SOURCES OF ACNA A NEW SENSE OF VIA MEDIA ACNA ANGLICANISM IS… DENOMINATIONAL IN DISTINCTIVES Certain features set Anglicanism apart from other branches of Christianity and denominations (e.g., currency): • Book of Common Prayer • 39 Articles of Religion (Elizabethan Settlement; Via Media) • GAFCON Jerusalem Declaration of 2008 (vs. TEC) • Provincial archbishops – w/ A. of Canterbury (first…) • Episcopal oversight – support and accountability ANGLICANISM IS… EPISCOPAL IN GOVERNANCE • Spiritual Authority – Regional & Pastoral • Provides Support & Accountability • Apostolic Succession? Continuity through history • NT 2-fold order: bishop/elder/pastor & deacons • Ignatius of Antioch (d. -

A Portrait of a Successful Pastor: Reanimating the Pastor As Shepherd in a Success Oriented Culture Steve Bontrager [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2018 A Portrait of a Successful Pastor: Reanimating the Pastor as Shepherd in a Success Oriented Culture Steve Bontrager [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Bontrager, Steve, "A Portrait of a Successful Pastor: Reanimating the Pastor as Shepherd in a Success Oriented Culture" (2018). Doctor of Ministry. 279. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/279 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY A PORTRAIT OF A SUCCESSFUL PASTOR: REANIMATING THE PASTOR AS SHEPHERD IN A SUCCESS ORIENTED CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY STEVE BONTRAGER PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2018 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Steve Bontrager has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 13, 2018 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Spiritual Formation. Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Deborah Loyd, DMin Secondary Advisor: Aaron Friesen, PhD Lead Mentor: MaryKate Morse, PhD Copyright © 2018 by Steve Bontrager All rights reserved. All Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version unless otherwise noted. -

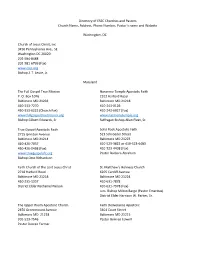

Directory of ESSC Churches and Pastors Church Name, Address, Phone Number, Pastor’S Name and Website

Directory of ESSC Churches and Pastors Church Name, Address, Phone Number, Pastor’s name and Website Washington, DC Church of Jesus Christ, Inc. 3456 Pennsylvania Ave., SE Washington DC 20020 202-584-8488 202-581-6799 (Fax) www.cojc.org Bishop J. T. Leslie, Jr. Maryland The Full Gospel True Mission Nazarene Temple Apostolic Faith P. O. Box 1076 2312 Harford Road Baltimore MD 21203 Baltimore MD 21218 410-233-7270 410-243-0126 410-333-6223 (Church Fax) 410-243-6027 (Fax) www.fullgospeltruemission.org www.nazarenetemple.org Bishop Gilbert Edwards, Sr. Suffragan Bishop Allan Fleet, Sr. True Gospel Apostolic Faith Solid Rock Apostolic Faith 2715 Grindon Avenue 523 Schroeder Street Baltimore MD 21214 Baltimore MD 21223 410-426-7037 410-523-3822 or 410-523-6483 410-426-0498 (Fax) 410-523-4408 (Fax) www.truegospelafc.org Pastor Barbara Abraham Bishop Otto Richardson Faith Church of the Lord Jesus Christ St. Matthew’s Holiness Church 2718 Harford Road 6205 Cardiff Avenue Baltimore MD 21218 Baltimore MD 21224 410-235-1957 410-631-7878 District Elder Nathaniel Nelson 410-631-7978 (Fax) Jurs. Bishop Milton Barge (Pastor Emeritus) District Elder Harrison W. Parker, Sr. The Upper Room Apostolic Church Faith Deliverance Apostolic 2450 Greenmount Avenue 3401 Court Street Baltimore MD 21218 Baltimore MD 21215 301-523-7546 Pastor Bernice Edwell Pastor Darren Farmer Restoration Through Christ Ministries Victory Deliverance Temple 3817 Janbrook Road 4401 Brinkley Road Randallstown MD 21133 Temple Hills MD 20748 443-272-6905 Suffragan Bishop Samford C. Brown Pastor James Jenkins Emmanuel Temple Church Bread of Life Ministries 10005 Old Columbia Road 4202 Seidel Avenue Columbia M.D. -

Theological Interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount

Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. 6.45 Theological Interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount The Early Church In the early church, the Sermon on the Mount was used apologetically to combat Marcionism and, polemically, to promote the superiority of Christianity over Judaism. The notion of Jesus fulfilling the law and the prophets (Matt. 5:17) seemed to split the difference between two extremes that the church wanted to avoid: an utter rejection of the Jewish matrix for Christianity, on the one hand, and a wholesale embrace of what was regarded as Jewish legalism, on the other hand. In a similar vein, orthodox interpretation of the sermon served to refute teachings of the Manichaeans, who used the sermon to support ideas the church would deem heretical. In all of these venues, however, the sermon was consistently read as an ethical document: Augustine and others assumed that its teaching was applicable to all Christians and that it provided believers with normative expectations for Christian behavior. It was not until the medieval period and, especially, the time of the Protestant Reformation that reading the sermon in this manner came to be regarded as problematic. Theological Difficulties Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. The primary difficulties that arise from considering the Sermon on the Mount as a compendium of Christian ethics are twofold. The first and foremost is found in the relentlessly challenging character of the sermon’s demands. Its commandments have struck many interpreters as impractical or, indeed, impossible, particularly in light of what the New Testament says elsewhere about human weakness and the inevitability of sin (including Matt. -

Pastor's Reference

PASTOR’S REFERENCE Parents: Please complete the portion below and submit this form to your pastor or the church leader who is most familiar with your family. Applicant should provide the person filing the reference with a stamped envelope addressed to the Director of Admissions. Applicant’s Family Name (Parent/Guardian) Last First Spouse Address Street City State ZIP Code Child(ren) Applying to Westminster (Names and Grades) Pastor/Leader: Please complete this form and return it within one week to Director of Admissions, Westminster Christian School, 2700 W. Highland Avenue, Elgin, IL 60124, fax to 847.695.0135, or email to [email protected]. The family named above is applying for admission to Westminster Christian School. Westminster honors Jesus Christ by providing an excellent education for the children of Christian parents. Westminster requires that at least one parent of each student be a professing Christian. We function best when our efforts can be combined with the Christian influence of the student’s home and church to provide a unified worldview. Since we feel that church attendance and active participation in the local church are essential for a child’s total education, we request that this form be completed by the family pastor as part of the admissions process. Please complete this form to the best of your knowledge. Your prompt attention is appreciated. Church Name Address Phone Street City State ZIP Code Denominational Affiliation Name of person completing this form Relationship with the family Pastor -

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS . Canon Law . Episcopal Directives . Diocesan Statutes and Norms •Diocesan statutes actually carry more legal weight than policy directives from . the Episcopal Conference . Parochial Norms and Rules CANON LAW . Applies to the worldwide Catholic church . Promulgated by the Holy See . Most recent major revision: 1983 . Large body of supporting information EPISCOPAL CONFERENCE NORMS . Norms are promulgated by Episcopal Conference and apply only in the Episcopal Conference area (the U.S.) . The Holy See reviews the norms to assure that they are not in conflict with Catholic doctrine and universal legislation . These norms may be a clarification or refinement of Canon law, but may not supercede Canon law . Diocesan Bishops have to follow norms only if they are considered “binding decrees” • Norms become binding when two-thirds of the Episcopal Conference vote for them and the norms are reviewed positively by the Holy See . Each Diocesan Bishop implements the norms in his own diocese; however, there is DIOCESAN STATUTES AND NORMS . Apply within the Diocese only . Promulgated and modified by the Bishop . Typically a further specification of Canon Law . May be different from one diocese to another PAROCHIAL NORMS AND RULES . Apply in the Parish . Issued by the Pastor . Pastoral Parish Council may be consulted, but approval is not required Note: On the parish level there is no ecclesiastical legislative authority (a Pastor cannot make church law) EXAMPLE: CANON LAW 522 . Canon Law 522 states that to promote stability, Pastors are to be appointed for an indefinite period of time unless the Episcopal Council decrees that the Bishop may appoint a pastor for a specified time .