Gagosian Gallery, the Former Director of the Tate Analyses His Career

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ivon Hitchens & His Lasting Influence

Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence 29 June - 27 July 2019 An exhibition of works by Ivon Hitchens (1893-1979) and some of those he influenced 12 Northgate, Chichester West Susssex PO19 1BA +44 (0)1243 528401 / 07794 416569 [email protected] www.candidastevens.com Open Wed - Sat 10-5pm & By appointment “But see Hitchens at full pitch and his vision is like the weather, like all the damp vegetable colours of the English countryside and its sedgy places brushed mysteriously together and then realised. It is abstract painting of unmistakable accuracy.” – Unquiet Landscape (p.145 Christopher Neve) The work of British painter Ivon Hitchens (1893 – 1979) is much-loved for his highly distinctive style in which great swathes of colour sweep across the long panoramic canvases that were to define his career. He sought to express the inner harmony and rhythm of landscape, the experience, not of how things look but rather how they feel. A true pioneer of the abstracted vision of landscape, his portrayal of the English countryside surrounding his home in West Sussex would go on to form one of the key ideas of British Mod- ernism in the 20thCentury. A founding member of the Seven & Five Society, the influential group of painters and sculptors that was responsible for bringing the ideas of the European avant-garde to London in the 30s, Hitchens was progres- sive long before the evolution of his more abstracted style post-war. Early on he felt a compulsion to move away from the traditional pictorial language of art school and towards the development of a personal language. -

New Self-Portrait by Howard Hodgkin Takes Centre Stage in National Portrait Gallery Exhibition

News Release Wednesday 22 March 2017 NEW SELF-PORTRAIT BY HOWARD HODGKIN TAKES CENTRE STAGE IN NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY EXHIBITION Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, 23 March – 18 June 2017 National Portrait Gallery, London Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music by Howard Hodgkin, 2011-2016, Courtesy Gagosian © Howard Hodgkin; Portrait of the artist by Miriam Perez. Courtesy Gagosian. A recently completed self-portrait by the late Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017) will go on public display for the first time in a major new exhibition, Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, at the National Portrait Gallery, London. Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music was completed by Hodgkin in late 2016 with the National Portrait Gallery exhibition in mind. The large oil on wood painting, (1860mm x 2630mm) is Hodgkin’s last major painting, and evokes a deeply personal situation in which the act of remembering is memorialised in paint. While Hodgkin worked on it, recordings of two pieces of music were played continuously: ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ composed by Jerome Kern and published in 1940, and the zither music from the 1949 film The Third Man, composed and performed by Anton Karas. Both pieces were favourites of the artist and closely linked with earlier times in his life that the experience of listening recalled. Kern’s song is itself a meditation on looking back and reliving the past. Also exhibited for the first time are early drawings from Hodgkin’s private collection, made while he was studying at Bath Academy of Art, Corsham in the 1950s. While very few works survive from this formative period in Hodgkin’s career, the drawings of a fellow student, Blondie, his landlady Miss Spackman and Two Women at a Table, exemplify key characteristics of Hodgkin’s approach which continued throughout his career. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge 09:15-09:40 Registration and coffee 09:45 Welcome 10:00-11:20 Session 1 – Chaired by Dr Alyce Mahon (Trinity College, Cambridge) Crossing the Border and Closing the Gap: Abstraction and Pop Prof Martin Hammer (University of Kent) Fellow Persians: Bridget Riley and Ad Reinhardt Moran Sheleg (University College London) Tailspin: Smith’s Specific Objects Dr Jo Applin (University of York) 11:20-11:40 Coffee 11:40-13:00 Session 2 – Chaired by Dr Jennifer Powell (Kettle’s Yard) Abstraction between America and the Borders: William Johnstone’s Landscape Painting Dr Beth Williamson (Independent) The Valid Image: Frank Avray Wilson and the Biennial Salon of Commonwealth Abstract Art Dr Simon Pierse (Aberystwyth University) “Unity in Diversity”: New Vision Centre and the Commonwealth Maryam Ohadi-Hamadani (University of Texas at Austin) 13:00-14:00 Lunch and poster session 14:00-15:20 Session 3 – Chaired by Dr James Fox (Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge) In the Thick of It: Auerbach, Kossoff and the Landscape of Postwar Painting Lee Hallman (The Graduate Center, CUNY) Sculpture into Painting: John Hoyland and New Shape Sculpture in the Early 1960s Sam Cornish (The John Hoyland Estate) Painting as a Citational Practice in the 1960s and After Dr Catherine Spencer (University of St Andrews) 15:20-15:50 Tea break 15:50-17:00 Keynote paper and discussion Two Cultures? Patrick Heron, Lawrence Alloway and a Contested -

Howard Hodgkin (1932 - 2017)

Cristea Roberts Gallery Artist Biography 43 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5JG +44 (0)20 7439 1866 [email protected] www.cristearoberts.com Howard Hodgkin (1932 - 2017) Howard Hodgkin was born in London in 1932. He studied at the 2013 Howard Hodgkin, Fondation Bemberg, Tolouse, France Camberwell School of Art and the Bath Academy of Art in the early Bengal Art Lounge and British Council Bangladesh 1950s. He first visited India in 1964, returning every year for many presents Howard Hodgkin, Gulshan, Bengal, India years. Hodgkin spent a period teaching until 1972. He was Trustee Tenth Anniversary Acquisitions, The Modern Art of the Tate Gallery, London from 1970-76 and of the National Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, USA Gallery, London from 1978-85. In 1984 he represented Britain at Howard Hodgkin: New Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, the XLI Venice Biennale with 24 paintings and was awarded the Rome, Italy second Turner Prize in 1985. He was knighted in 1992 and made a 2012 Acquainted with the Night, Alan Cristea Gallery, London, Companion of Honour in 2002. UK Howard Hodgkin, Tate Britain, London, UK His work has been the subject of numerous major retrospectives 2011 Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA around the world, most notably at the Metropolitan Museum, New Small Prints: Abstractions in Colour, Meyer Fine Art, York, in 1995, at Tate Britain, London, in 2006, and at the National San Diego, USA Portrait Gallery, London, in 2017. His paintings and prints are 2010 Time and Place: Paintings 2001-2010, De Pont Museum held in major museums and collections worldwide. -

Press Release September 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Cristea Roberts Gallery Press Release September 2019 43 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5JG Press Contact: +44 (0)20 7439 1866 Gemma Colgan [email protected] [email protected] www.cristearoberts.com +44 (0)20 7439 1866 Howard Hodgkin: Strictly Personal Part I 31 October - 23 November 2019 Part II 28 November - 21 December 2019 increased with hand-painting giving richness to the printed surface. This was the beginning of the hybrid labour intensive process which Hodgkin was to employ for the rest of his career. During this time Hodgkin began to work with some of the best printers in America and Europe, including Petersburg Press in New York and Aldo Crommelyck in Paris, who was responsible for so many of the most accomplished graphic works by Braque, Picasso and Matisse. Examples from this period include Bed, 1978, Breakfast, 1978 and Storm, 1977. In 1986 Hodgkin made the acquaintance of master printer Jack Shireff who introduced him to carborundum printing, a method which allowed the artist to increase the emotional intensity of his printed work by adding texture and depth to his work. By introduc- ing gritty silica compounds to the plate, Hodgkin was now able to apply colour directly with a brush, creating etchings with painterly Howard Hodgkin; Strictly Personal, 2000-2002 effects, such as Red Palm and Black Monsoon, both executed in 1987. Howard Hodgkin: Strictly Personal is a retrospective survey of prints by Sir Howard Hodgkin (1932 - 2017) on display at Cristea “Howard’s prints became bigger and more complex from the late Roberts Gallery from 31 October until 21 December 2019. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1980

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1980 Tate Gallery Millbank London SW1 01-821 5323 • -• The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held at Painter's Hall 9, Little Trinity Lane, EC4 on Wednesday, July 1st, 1981 at 8.45 p.m. 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended December 31, 1980, together with the auditor's report. 2. To reappoint Sayers Butterworth as auditors of the society in accordance with section 14 of the Companies Act, 1976, and to authorize the committee to determine their remuneration for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee the following who have been duly nominated: Mary Rose Beaumont, Ronnie Duncan, James Hoiioway, Edward Lucie-Smith, Jeremy Rees and Alan Roger. The retiring members are Lord Croft and Gabrielle Keiller. 4. Any other business By order of the Committee Pauline Vogelpoe! June 1 1981 Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in London No 255486 Charities Registration No 208178 Phoenix 480/540 1980 56 x 71 cm/22 x 28 in. From an edition of unique collaged images screenprinted by Megara and published in 1981 by iht Contemporary Art Society, Tats Gallery, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother At the Contemporary Art Society's iast annual general meeting a resolution was carried with unanimous enthusiasm respectfully congratulating our patron, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, on her 80th birthday. In reply her private secretary told us how touched she was by the society's very kind message and expressed her appreciation. -

000000560.Sbu.Pdf (493.3Kb)

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... R. B. Kitaj’s Paintings In Terms of Walter Benjamin’s Allegory Theory A Thesis Presented by Bo-Kyung Choi to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2009 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Bo-Kyung Choi We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Arts degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Donald Kuspit – Thesis Advisor Distinguished Professor of Art History department Andrew Uroskie – Chairperson of Defense Assistant Professor of Art History department This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis R. B. Kitaj’s Paintings In Terms of Walter Benjamin’s Allegory Theory by Bo-Kyung Choi Master of Arts in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2009 This thesis investigates R.B. Kitaj’s later paintings since the 1980s, focusing on his enthusiasm for fragments. While exploring diverse media from print to painting throughout his work, his main interest was the use of fragments, which in turn revealed his broader interests in the notion of historicity as fragments detached from its original context. Such notion based on Walter Benjamin’s theory of allegory allowed him to embrace a much more comprehensive theme of Jewishness as the subject of his painting. -

Howard Hodgkin the Complete Paintings: Catalogue Raisonnae Free

FREE HOWARD HODGKIN THE COMPLETE PAINTINGS: CATALOGUE RAISONNAE PDF Marla Price,John Elderfield | 420 pages | 01 Sep 2006 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500093290 | English | London, United Kingdom Howard Hodgkin prints : a catalogue raisonné / | University of Toronto Libraries Loers, Viet et al. Text in English and German. Ratcliff, Carter. Small folio, wraps. New York, Rizzoli, Varichon, Anne. Paris, Somogy, This important publication on French painter Albert Gleizes gathers nearly 2, works in all media, including oils, watercolors, drawings, and gouaches. Based on research by Gleizes scholar Hauptman, William. Princeton, Princeton University Press, Although recognized chiefly for his role as a Serra, Tomas Llorens. II - Folio, cloth. Text in English and Spanish. Elger, D. Large 4tos, boards. Stuttgart, Cantz, Published to accompany an exhibition at the Sprengel Museum and includes a compendium of texts on the artist's life and work. Text in Jordan, Jim and Robert Goldwater. Large 4to, cloth. Carmean, Jr. Cooper, Douglas. Folio, cloth, slight wear. Paris, Berggruen, One of an edition Howard Hodgkin the Complete Paintings: Catalogue Raisonnae copies. Freitag Semff, Michael. Munich, Sieveking, Dirie, Clement and Cara Jordan. Zurich, JRP Ringier, Stebbins, Theodore E. With the assistance of Janet L. Comey and Karen E. Quinn; pp. New Haven, Yale University Press, Drawing on his Evans, David. New York, Kent Fine Art, Hodin, J. Small folio, cloth. Boston, Boston Book and Art Shop, Bowness, Alan, ed. New York, Praeger, Barrette, Bill. New York, Timken Publishers, Scottish Arts Council. Price, Marla. Introduction by John Elderfield; pp. Heenk, Liesbeth. Introduction by Nan Rosenthal; pp. New York, Thames and Hudson, The first ever comprehensive survey and catalogue raisonne of Hodgkin's prints, more than works made since Villiger, Suzi ed. -

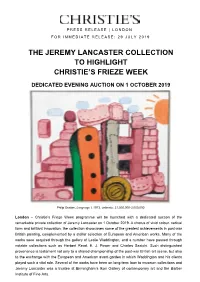

The Jeremy Lancaster Collection to Highlight Christie’S Frieze Week

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 29 JULY 2 0 1 9 THE JEREMY LANCASTER COLLECTION TO HIGHLIGHT CHRISTIE’S FRIEZE WEEK DEDICATED EVENING AUCTION ON 1 OCTOBER 2019 Philip Guston, Language I, 1973, estimate: £1,500,000-2,000,000 London – Christie’s Frieze Week programme will be launched with a dedicated auction of the remarkable private collection of Jeremy Lancaster on 1 October 2019. A chorus of vivid colour, radical form and brilliant innovation, the collection showcases some of the greatest achievements in post-war British painting, complemented by a stellar selection of European and American works. Many of the works were acquired through the gallery of Leslie Waddington, and a number have passed through notable collections such as Herbert Read, E. J. Power and Charles Saatchi. Such distinguished provenance is testament not only to a shared championship of the post-war British art scene, but also to the exchange with the European and American avant-gardes in which Waddington and his clients played such a vital role. Several of the works have been on long-term loan to museum collections and Jeremy Lancaster was a trustee at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery of contemporary art and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts. A frequent traveller with a keen appetite for art and knowledge, Jeremy Lancaster was in part influenced by the seminal exhibition ‘A New Spirit in Painting’. Undoubtedly a profound moment in the landscape of contemporary art it was staged by London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1981. The direction of his collecting taste follows a similar dedication to transatlantic discourse in paintings from Frank Auerbach and Howard Hodgkin to Philip Guston, Robert Ryman and Josef Albers. -

Richard Allen – an Important Retrospective at Offer Waterman & Co

RICHARD ALLEN – AN IMPORTANT RETROSPECTIVE AT OFFER WATERMAN & CO Untitled Op Art painting (1966), 91x91cms, PVA on board. Richard Allen was at the cutting edge of abstract art during a crucial phase in its development during the 1960’s and 1970’s, working alongside some of the best known names in British modernism such as Bridget Riley yet always remaining very much his own man. However his decision to move to the Channel Islands in 1977 took him away from the hub of the London art world and meant that subsequently he received less recognition than he deserved. Richard Allen: A Retrospective , to be held at Offer Waterman & Co in London from 16 April to 10 May 2008 , will be the first major exhibition of his work since his death in 1999 and aims to restore him to his rightful place in the history of late 20 th century art. None of the paintings and works on paper in the exhibition at Offer Waterman & Co at 11 Langton Street, London SW10 have been on the market before and all have come from his estate following a decision by his family to sell them. “I have a very clear reason for doing this,” said his daughter Rebecca, who lives in Sheffield. “I felt awful that these works were in storage. The work was painted to be sold. He painted for his own pleasure and passion but he always wanted to sell the work so that it would be on view. We want the paintings to be on walls in other people’s homes and public galleries.” Richard Allen: A Retrospective will include more than 40 works including Op art paintings, Pop art collages, charcoal paintings, colour studies and some of Allen’s ‘white paintings’ which he concentrated on in the mid-1990’s. -

Complete Price List

Patrick Caulfield CBE RA 1936-2005 . .. 1956-1960 Chelsea College of Art, London 1960-1963 Royal College of Art, London 1963-1971 Taught at Chelsea College of Art, London 1995 Awarded the Jerwood Painting Prize (jointly with Maggi Hambling) 1996 Awarded CBE SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1964 & 1967 Robert Fraser Gallery, London 1966 & 1968 Robert Elkon Gallery, New York 1969 Waddington Galleries, London (prints) 1971 Waddington Galleries, London; D.M.Gallery, London (prints) 1972 Sweeney Reed Galleries, Victoria, Australia 1973 Waddington Galleries, London (print retrospective) 1974 O.K. Harris Works of Art, New York 1975 Waddington Galleries, London; Scottish Arts Council Gallery, Edinburgh; Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool 1976 'Patrick Caulfield : Recent Paintings and Prints', Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol 1977 Tortue Gallery, Santa Monica, California (print retrospective) : touring to Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona 1978 'Tate Gallery', London (prints) 1979 Waddington Galleries, London 1980 Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, Australia; Welsh Arts Council Print Exhibition, Garner Centre for the Arts, University of Sussex, Brighton : touring to Midland Group, Nottingham; Oriel, Cardiff 1981 'Patrick Caulfield : Paintings 1963-81', Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool (retrospective, touring to Tate Gallery, London); Waddington Galleries, London 1982 Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo (retrospective) 1983 Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol (print retrospective) 1985 Waddington Galleries, London 1985-1987 National Museum of Fine Art, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (British Council print