Elsie Walker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

Cinematic Hamlet Arose from Two Convictions

INTRODUCTION Cinematic Hamlet arose from two convictions. The first was a belief, confirmed by the responses of hundreds of university students with whom I have studied the films, that theHamlet s of Lau- rence Olivier, Franco Zeffirelli, Kenneth Branagh, and Michael Almereyda are remarkably success- ful films.1 Numerous filmHamlet s have been made using Shakespeare’s language, but only the four included in this book represent for me out- standing successes. One might admire the fine acting of Nicol Williamson in Tony Richard- son’s 1969 production, or the creative use of ex- treme close-ups of Ian McKellen in Peter Wood’s Hallmark Hall of Fame television production of 1 Introduction 1971, but only four English-language films have thoroughly transformed Shakespeare’s theatrical text into truly effective moving pictures. All four succeed as popularizing treatments accessible to what Olivier’s collabora- tor Alan Dent called “un-Shakespeare-minded audiences.”2 They succeed as highly intelligent and original interpretations of the play capable of delight- ing any audience. Most of all, they are innovative and eloquent translations from the Elizabethan dramatic to the modern cinematic medium. It is clear that these directors have approached adapting Hamlet much as actors have long approached playing the title role, as the ultimate challenge that allows, as Almereyda observes, one’s “reflexes as a film-maker” to be “tested, battered and bettered.”3 An essential factor in the success of the films after Olivier’s is the chal- lenge of tradition. The three films that followed the groundbreaking 1948 version are what a scholar of film remakes labels “true remakes”: works that pay respectful tribute to their predecessors while laboring to surpass them.4 As each has acknowledged explicitly and as my analyses demonstrate, the three later filmmakers self-consciously defined their places in a vigorously evolving tradition of Hamlet films. -

December 2020 Download

December 2020 Program Updates from VP and Program Director Doron Weber FILM Son of Monarchs Awarded 2021 Sloan Feature Film Prize at Sundance Son of Monarchs has been chosen as the Sloan Feature Film Prize winner at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, to be awarded in January at this year’s virtual festival. The feature film, directed and written by filmmaker and scientist Alexis Gambis, follows a Mexican biologist who studies butterflies at a NYC lab as he returns home to the Monarch forests of Michoacán. The film was cited by the jury “for its poetic, multilayered portrait of a scientist’s growth and self-discovery as he migrates between Mexico and NYC working on transforming nature and uncovering the fluid boundaries that unite past and present and all living things.” This year’s Sloan jury included MIT researcher and protagonist of the new Sloan documentary Coded Bias Joy Buolamwini, Associate Professor in Chemistry at CUNY Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center Mandë Holford, and Sloan-supported filmmakers Aneesh Chaganty (Searching), Lydia Dean Pilcher (Radium Girls), and Lena Vurma (Adventures of a Mathematician). Son of Monarchs will be included in the 2021 Sundance Film Festival program and will be recognized at the closing night award ceremony as the Sloan winner. The Sloan Feature Film Prize, one of only six juried prizes at Sundance, is supported by a 2019 grant to the Sundance Institute. Ammonite Wins Sloan Science in Cinema Award at SFFILM This year’s SFFILM Sloan Science in Cinema Prize, which recognizes the compelling depiction of science in a narrative feature film, was awarded to Ammonite. -

Legally Blonde Jr Playbill

Legally Blonde, JR. CAST DELTA—July 9 and 11 Margot Avery Neyland Serena Sara Waldbauer Pilar Cianna Brewer Gaelen Grace Bethany Kate Lauren Tanaka Elle Woods Kate Rodenmeyer Saleswoman Addie Matthews Store Manager Xenia Minton Warner Alex Forbes Grandmaster Chad Darby Frost Winthrop Jackson Haber Lowell Harrison Speed Pforzheimer Jacob Jones Jet Blue Pilot Casey Stringer Emmett Justin Bell Aaron Oliver Long Padamadan Max Nelson Enid Nina Frost Vivienne Tonya Shenoy Callahan Matthew McMurtry Paulette Tykala Barnes Whitney Victoria Chough Dewey Elijah Mangum Brooke Wyndham Emani Sullivan Sabrina Yasmine Ware Prison Guard Aaliyah Newsome Kyle Riley Collins Kiki Shasa Cohran Cashier Camille Halverson Stylist Meredith Jones Bookish Client Jory Tanaka Chutney Baileigh Hughes Bailiff Kade Perruso Judge Megan Gautier Ensemble Wake Monroe, Matthew Jordan, Amber Robinson, Ariana Bridges, Emily Rutland, Isabella Ragazzi NU—July 10 and 12 Margot Claire Porter Serena Lamiorkor Lawson Pilar Anna Rose Myrick Gaelen Rachel Regan Kate Reese Overstreet Elle Woods Chesney Mitchell Saleswoman Bailey Graves Store Manager Katherine Kelly Warner Jabarrie Evans Grandmaster Chad Jeffrey Cornelius Winthrop Walker Palmerton Lowell Samuel Ball Pforzheimer Charlie Corkern Jet Blue Pilot Myla Toaster Emmett Ben Sanders Aaron Devin Ranftle Padamadan Parker Moak Enid Fikumni Idowu Vivienne Taylor Gray Callahan Michael Maloney Paulette Madeline Porter Whitney Mia Hammond Dewey Dale Shearer Brooke Wyndham Miles Taylor Leverette Sabrina Perry DeLoach Prison Guard Karis Irwin Kyle Alex Mangieri Kiki Udoka Robertson Cashier Hayley Palmerton Stylist Lily Garretson Bookish Client Lanae Williams Chutney Kacie McAuliffe Bailiff Robert Archer Judge Ivy Graham Ensemble: John Matthews, Aly Sebren, Chandler Ray, Verlecia Gavin, Lili Hobdy, Jessica Smith Please Note That photography, videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. -

Something Rotten DISCUSSION GUIDE

Something Rotten DISCUSSION GUIDE “One thing was for sure. Something was rotten in Denmark, Tennessee, and it wasn't just the stink from the paper plant..” - Horatio Wilkes About the Book Denmark,Tennessee stinks.Bad.The smell hits Olivia Mendelsohn is determined to clean up the Horatio Wilkes the moment he pulls into town to river-and the Prince family that's been polluting it for visit his best friend, Hamilton Prince.And it's not just decades. Hamilton's mom,Trudy Prince, just married the paper plant and the polluted Copenhagen River her husband's brother, Claude, and signed over half that's stinking up Denmark: Hamilton's father has of the plant and profits.And then there's Ford N. been poisoned and the killer is still at large. Branff,Trudy's old flame, who's waging a hostile takeover of Elsinore Paper. Why? Because nobody believes Rex Prince was murdered. Nobody except Horatio and Hamilton. Motive, means, opportunity--they all have them. But They need to find the killer before someone else who among them has committed murder most foul? dies, but it won't be easy. It seems like everyone's a If high school junior Horatio Wilkes can just get past suspect. Hamilton's hot, tree-hugging ex-girlfriend the smell, he might get to the bottom of all this. Pre-reading Questions for Discussion Activity Comprehension Why is Horatio the main character in Something Rotten, and not Pulp Shakespeare Hamilton? The character of Horatio Wilkes is inspired by noir Horatio is big on promises.Which promises does he keep, and detectives like Philip Marlowe which does he abandon? What are his reasons? and Sam Spade. -

By William Shakespeare | Directed by Annie Lareau

By William Shakespeare | Directed by Annie Lareau All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Touring acting companies already had a long history in Shakespeare’s time. Before 1576, there were no theaters in England, and so all actors would travel from town to town to perform their plays. Travel was difficult in Elizabethan England. Not only was the travel slow, but there were dangers of getting attacked by thieves or of catching the plague! Traveling troupes of actors were sponsored by the nobility, who enjoyed the entertainment they provided. They would need a license from a Bailiff to be able to travel around England performing, and these licenses were only granted to the aristocracy for them to maintain their acting troupes. The actors also needed support from their patrons to be able to wear clothing of the nobility! England’s Sumptuary Laws prohibited anyone from wearing clothing above their rank unless they were given to them and approved by their noble patron. Today, much has changed in how we tour our Shakespearean plays, but there are still many similarities between our tour and those early acting troupes. We travel from town to town across the state of Washington, battling long drives, traffic, and snow in the mountain passes to get there safely and perform for the enjoyment of our audiences. We also could not do this tour without the generous support of our own sponsors, who help underwrite our travel, support scholarships for schools in need, and help us pay for costume and set upgrades. Just like the Elizabethan acting troupes, we could not do it without support from our generous, Shakespeare-loving patrons! Thank you for booking a Seattle Shakespeare Company touring show at your school. -

Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama

"Revenge Should Have No Bounds": Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Woodring, Catherine. 2015. "Revenge Should Have No Bounds": Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463987 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “Revenge should have no bounds”: Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama A dissertation presented by Catherine L. Reedy Woodring to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Catherine L. Reedy Woodring All rights reserved. Professor Stephen Greenblatt Catherine L. Reedy Woodring “Revenge should have no bounds”: Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama Abstract The revenge- and poison- filled tragedies of seventeenth century England astound audiences with their language of contagion and disease. Understanding poison as the force behind epidemic disease, this dissertation considers the often-overlooked connections between stage revenge and poison. Poison was not only a material substance bought from a foreign market. It was the subject of countless revisions and debates in early modern England. Above all, writers argued about poison’s role in the most harrowing epidemic disease of the period, the pestilence, as both the cause and possible cure of this seemingly contagious disease. -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions. -

SHAKESPEARE Summer School in Verona, Italy, 1-5 July 2019

SHAKESPEARE Summer School in Verona, Italy, 1-5 July 2019 " in fair Verona, where we lay our scene” Programme Dates: 1-5 July 2019 Convenors Dr Victoria Bladen (University of Queensland, Australia) [email protected] Prof Chiara Battisti (University of Verona) [email protected] Prof Sidia Fiorato (University of Verona) [email protected] Venue Università di Verona, Polo Universitario S. Marta, Via Cantarane, 24, 37129 Verona VR , Room SMT10 www.univr.it/it; http://comunicazione.univr.it/santamarta/index.html Day 1 Monday 1 July 10.00 – 10.30: Welcome to Verona and the summer school: Prof. Alessandra Tomaselli, Head of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures – University of Verona; Prof. Matteo de Beni, Head of the Teaching Board of Foreign Languages and Literatures– Department of Foreign Languages – University of Verona. Dr. Victoria Bladen, Prof. Chiara Battisti, Prof. Sidia Fiorato 10.30 – 11.30: Introduction to Shakespeare – Prof. Chiara Battisti and Prof Sidia Fiorato 11.30 – 12.00: Will Power – why we study Shakespeare – Dr Victoria Bladen 12.00 – 12.30: Renaissance cities and Shakespeare - Maddison Kennedy (student, University of Queensland) 12.30 – 1.30: Lunch break 1.30 – 2.00: Introduction to Romeo and Juliet – Dr Victoria Bladen 2.00 – 3.15: Playreading: Romeo and Juliet 3.15 – 3.30: break 3.30 - 5.00: Playreading: Romeo and Juliet continued. Day 2 Tuesday 2 July Shakespeare and Popular Culture 10.00 – 10.30: Shakespeare and Comics– Prof Chiara Battisti 10.30 – 11.00: Shakespeare and Popular Culture – Prof Sidia Fiorato 11.00 – 12.30: Playreading: Romeo and Juliet 12.30 – 1.30: Lunch break Shakespeare and Gender 1.30 –2.00 Masculine Adornment: The Androgyne and Gender Unease in The Two Gentlemen of Verona and Romeo & Juliet – Matthew Huxley (Hons student, University of Queensland) Shakespeare and His Contemporaries 2.00 – 2.30: Shakespeare and Cervantes – Prof. -

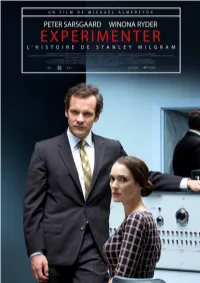

Experimenter Dp 2

!2 w w w . s e p t i e m e f a c t o r y . c o m Présente EXPERIMENTER réalisé par MICHAEL ALMEREYDA Avec PETER SARSGAARD WINONA RYDER USA - 2015 Durée : 1H30 – Format : 1:85 – Son : DOLBY 5.1 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 18 NOVEMBRE 2015 DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE SEPTIEME FACTORY BOSSA NOVA 20, rue du Neuhof Michel Burstein 67100 Strasbourg 32, Bld Saint Germain [email protected] 75005 Paris [email protected] Tel : 01 43 26 26 26 [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info !3 !4 Synopsis Yale Université, 1961, Stanley Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard) conduit une expérience de psychologie - encore majeure aujourd’hui - dans laquelle des volontaires croient qu’ils administrent des décharges électriques douloureuses à un parfait inconnu (Jim Gaffigan) attaché à une chaise, dans une autre pièce. Malgré les demandes de la victime d’arrêter, la majorité des volontaires continuent l’expérience, infligeant ce qu’elles croient être des décharges presque mortelles, simplement parce qu’un scientifique leur a demandé de le faire. A l'époque où le procès du Nazi Eichmann est diffusé à la télévision jusque dans les foyers de millions d'américains, la théorie développée par le scientifique Milgram, qui explore la tendance des individus à se soumettre à une autorité, provoque une vive émotion dans l'opinion publique et la communauté scientifique. Célébré par nombre de ses confrères il est vilipendé par d'autres. Stanley Milgram est alors accusé de tromperie et de manipulation. Son épouse Sasha (Winona Ryder) le soutient dans cette période de trouble. -

Introduction: the Shakespeare Test

C H A P T E R O N E ᨰ Introduction: The Shakespeare Test That’s what I like about Shakespeare; it’s the pictures. —Al Pacino, Looking for Richard The making of Shakespeare films dates nearly from the start of commer- cial presentations of the cinematic medium. In the earliest screen adapta- tions from Shakespeare, there were palpable tensions at work, not only between aesthetic and financial objectives, but also between developing notions of what film is and does. One filmic impulse is to document, but with Shakespeare there are any number of subjects worth documenting: the playtext, a particular theatrical realization of that playtext, or the his- torical conditions reflected or represented in either playtext or stage ver- sion. Another filmic impulse is, of course, to tell a story: here, too, Shake- speare’s playtexts offer an embarassment of rich possibilities. Further complicating matters are the uneasy, inescapable relations that the genres of nonfictional and fictional film bear with one another. The problem of distinguishing between modes of representation and ways of manipulat- ing materials (Plantinga 9–12) is as old as narrative filmmaking itself, and Shakespeare very quickly became part of the developing dilemma. It was in the 1890s that Georges Méliès pioneered the practice of storytelling through the exciting new medium; he also pioneered the 1 2 SHAKESPEARE IN THE CINEMA practice of borrowing from familiar materials, such as the Faust legend in The Cabinet of Mephistopheles (1897) or Charles Perrault’s account of Cin- derella (1899). Méliès would later borrow from Shakespeare—an abridged Hamlet and a film, starring himself, about the composition of Julius Caesar, both in 1907—but his were not the first Shakespeare films. -

Hamlet As Shakespearean Tragedy: a Critical Study

SHAKESPEAREAN TRAGEDY HAMLET AS SHAKESPEAREAN TRAGEDY: A CRITICAL STUDY Rameshsingh M.Chauhan ISSN 2277-7733 Assistant Professor, Volume 8 Issue 1, Sardar Vallabhbhai Vanijya Mahavidyalaya,Ahmedabad June 2019 Abstract Hamlet is often called an "Elizabethan revenge play", the theme of revenge against an evil usurper driving the plot forward as in earlier stage works by Shakespeare's contemporaries, Kyd and Marlowe, as well as by the .As in those works avenging a moral injustice, an affront to both man and God. In this case, regicide (killing a king) is a particularly monstrous crime, and there is no doubt as to whose side our sympathies are disposed. The paper presents the criticism of Hamlet as Shakespearean tragedy. Keywords: Hamlet, Tragedy, Shakespeare, Shakespearean Tragedy As in many revenge plays, and, in fact, several of Shakespeare's other tragedies (and histories), a corrupt act, the killing of a king, undermines order throughout the realm that resonates to high heaven. We learn that there is something "rotten" in Denmark after old Hamlet's death in the very first scene, as Horatio compares the natural and civil disorders that occurred in Rome at the time of Julius Caesar's assassination to the disease that afflicts Denmark. These themes and their figurative expression are common to the Elizabethan revenge play genre in which good must triumph over evil.Throughout Hamlet we encounter a great deal of word play, Shakespeare using a vast number of multivalent terms ranging from gross puns to highly-nuanced words that evoke a host of diverse associations and images. While Hamlet can tell this difference between a "hawk and a handsaw," the play challenges the assumption that language itself can convey human experience or hold stable meaning.