Appellants' Joint Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Ballot Democratic Primary Jefferson County, Alabama June 5, 2018

SAMPLE BALLOT DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA JUNE 5, 2018 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER FOR CIRCUIT COURT JUDGE, FOR JUDGE OF PROBATE TO VOTE YOU MUST BLACKEN 10TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, JEFFERSON COUNTY, THE OVAL ( ) COMPLETELY! PLACE NO. 27 PLACE NO. 2 (VOTE FOR ONE) (VOTE FOR ONE) DO NOT MAKE AN X. IF YOU SPOIL YOUR BALLOT, AMBER LADNER WILLIE "REDTAPE" FLORENCE SR. DO NOT ERASE, BUT ASK FOR A NEW BALLOT. ALARIC MAY SHERRI COLEMAN FRIDAY FOR GOVERNOR FOR DISTRICT ATTORNEY, JAMERIA MOORE (VOTE FOR ONE) 10TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT (VOTE FOR ONE) FOR JEFFERSON COUNTY SHERIFF (VOTE FOR ONE) SUE BELL COBB DANNY CARR CHRISTOPHER A. COUNTRYMAN RAYMOND L. JOHNSON, JR. WALLACE ANGER JR. JAMES C. FIELDS, JR. FOR DISTRICT COURT JUDGE, HEATH BOACKLE 10TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, WALT MADDOX PLACE NO. 3 WILSON HALE (VOTE FOR ONE) DOUG "NEW BLUE" SMITH FREDERIC BOLLING MARK L. PETTWAY ANTHONY WHITE CLOTELE HARDY "C.H." BRANTLEY FOR MEMBER, JEFFERSON COUNTY COMMISSION FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL PAMELA WILSON COUSINS DISTRICT NO. 1 (VOTE FOR ONE) (VOTE FOR ONE) STEPHANIE A. HUNTER GEORGE F. BOWMAN SR. CHRIS CHRISTIE LASHUNTA "SHUN" WHITE-BOLER ERIC MAJOR JOSEPH SIEGELMAN FOR DISTRICT COURT JUDGE, GARY RICHARDSON 10TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, PLACE NO. 9 LASHUNDA SCALES FOR STATE REPRESENTATIVE, (VOTE FOR ONE) DISTRICT NO. 54 (VOTE FOR ONE) KECHIA DAVIS JEROME DEES GLENDA FREEMAN JACQUELINE GRAY MILLER SHEILA WEIL NEIL RAFFERTY DEBRA WESTON-PICKENS FOR SECRETARY OF STATE LOU WILLIE FOR STATE DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE (VOTE FOR ONE) COMMITTEE FEMALE DISTRICT NO. 54 FOR CIRCUIT CLERK, (VOTE FOR ONE) JEFFERSON COUNTY (VOTE FOR ONE) LULA ALBERT "SGM RET" BRIT BLALOCK HEATHER MILAM JACKIE ANDERSON-SMITH PATRICIA TODD FOR CIRCUIT COURT JUDGE, SARAH E. -

2018 Corporate Political Contributions to State Candidates and Committees

Corporate Political Contributions¹ to State Candidates and Committees Alabama 2018 Candidate or Committee Name Party-District Total Amount STATE SENATE Tim Melson R-01 $1,000 Greg Reed R-05 $1,000 Steve Livingston R-08 $1,000 Del Marsh R-12 $1,000 Jabo Waggoner R-16 $1,000 Greg Albritton R-22 $1,000 Bobby Singleton D-24 $1,000 Chris Elliott R-32 $1,000 Vivian Davis Figures D-33 $1,000 Jack Williams R-34 $1,000 David Sessions R-35 $1,000 STATE HOUSE Lynn Greer R-02 $500 Kyle South R-16 $500 Laura Hall D-19 $500 Nathaniel Ledbetter R-24 $500 David Standridge R-34 $500 Jim Carns R-48 $500 Harry Shiver R-64 $500 Elaine Beech D-65 $500 Pebblin Warren D-82 $500 Paul Lee R-86 $500 Chris Sells R-90 $500 Mike Jones R-92 $1,000 Steve Clouse R-93 $500 Joe Faust R-94 $500 Steve McMillian R-95 $500 Matt Simpson R-96 $500 Aldine Clarke D-97 $500 Napoleon Bracy D-98 $500 Sam Jones D-99 $500 Victor Gaston R-100 $500 Chris Pringle R-101 $500 Shane Stringer R-102 $500 Barbara Drummond D-103 $500 Margie Wilcox R-104 $500 Corporate Political Contributions¹ to State Candidates and Committees Alabama 2018 Candidate or Committee Name Party-District Total Amount STATE HOUSE cont’d. Chip Brown R-105 $500 OTHER Will Ainsworth R-Lt. Governor $1,000 Kay Ivey R-Governor $5,000 California 2018 Candidate or Committee Name Party-District Total Amount STATE SENATE Susan Rubio D-22 $1,000 Patricia Bates R-36 $2,500 Ben Hueso D-40 $2,500 STATE ASSEMBLY Brian Dahle R-01 $2,500 Jim Cooper D-09 $2,000 Jim Frazier D-11 $2,000 Tim Grayson D-14 $2,000 Catharine Baker R-16 $1,000 -

I N S I D E Voteothers Travel Alabama Retail Choices for Alabama to D.C

WWW.ALABAMARETAIL.ORG VOLUME 14, NUMBER 2 B ENEFIT FROM THE VALUE. Alabama T H I S I S S U E Retail officers, I N S I D E VOTEothers travel Alabama Retail choices for Alabama to D.C. to Association retailers in the July 15 urge e-fairness — In the June 3 primary, primary runoffs. Don’t 93 percent of the can- recommends these candidates as the best run off on the runoff. ive Alabama Retail didates Alabama Retail Association members endorsed were elected, PRIMARY RUNOFF BALLOT met in mid-June with nominated or won a runoff JULY 15, 2014 F Alabama’s congressional position. Plan to go to the polls again July members and staff to 15 and consider voting for the candidates THESE OFFICES WILL APPEAR ON ALL REPUBLICAN PRIMARY BALLOTS present their case on the backed by Alabama Retail. need for passage of federal e-fairness legislation this FOR — Clothiers, a jeweler, year. SECRETARY FOR PSC, a furniture store owner “Congress can send a OF STATE Place No. 2 and a grocery representa- powerful message that they (Vote for ...) (Vote for ...) tive traveled to Washing- support small business by ton, D.C., on behalf of all ending policies that pick Alabama retailers to advocate for the pas- JOHN MERRILL CHIP BEEKER winners sage of the Marketplace Fairness Act this and losers year. They told Congress to quit picking THESE OFFICES WILL APPEAR ON REPUBLICAN PRIMARY in the free BALLOTS IN THESE DISTRICTS winners and losers when it comes to who market,” collects sales taxes. FOR UNITED STATES FOR said George REPRESENTATIVE, STATE SENATOR, Wilder, — Alabama Retail’s 6th District No. -

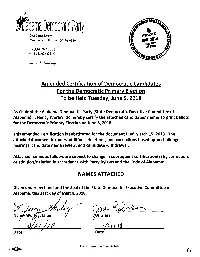

Certification of Candidates

taoama Democrn!lc Par!~ Post Office Box 950 Montgomery, Alabama 36101-0950 p - 334.262.2221 f- 334.262.6474 www.aladems.org Amended Certification of Democratic Candidates For the Democratic Primary Election To be Held Tuesday, June 5, 2018 As Chair of the Alabama Democratic Party (State Democratic Executive Committee of Alabama), I, Nancy Worley, do hereby certify the attached candidates' names to print ballots for the Democratic Primary Election on June 5, 2018. This amended Certification is substituted for the document filed March 15, 2018. The attached document includes additions, deletions, and corrections based upon challenge hearings, candidate name review, and candidate withdrawal. Attached names as follows are subject to change in subsequent certification(s) by correction, or addition/deletion in accordance with Party Bylaws and the Code of Alabama: NAMES ATTACHED Given under my hand and the Seal of the State Democratic Executive Committee of Alabama, this 21st day of March, 2018 . .3/~1 );R Date Date Paid for by the Alabama Democratic Party Official list of Democratic Candidates for 2018 Congressional Candidates US House District 1- Robert Kennedy, Jr. US House District 1- Lizzetta Hill McConnell US House District 2- Tabitha Isner US House District 2- Audri Scott Williams US House District 3- Mallory Hagan US House District 3- Adia McClellan Winfrey US House District 4- Lee Auman US House District 4- Rick Neighbors US House District 5- Peter Joffrion US House District 6- Danner Kline US House District 7- Terri A. Sewell Statewide Candidates Governor- Sue Bell Cobb Governor- Christopher A. Countryman Governor- James C. -

Alabama Certificate of Ascertainment 2020

STATE OF ALABAMA PROCLAMATION BY THE GOVERNOR CERTIFICATE OF ASCERTAINMENT I, Kay Ivey, Governor of the State of Alabama, do hereby certify that on November 23, 2020, the Governor, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of State of the State of Alabama canvassed the vote from the November 3, 2020 general election in the State of Alabama for President and Vice President of the United States, as provided by the laws of the State of Alabama, and ascertained that the vote for electors was as follows: ALABAMA DEMOCRATIC PARTY Electors pledged to Joseph R. Biden and Kamala D. Harris: Name Votes received Brooke Tanner Battle 849,624 Linda Coleman-Madison 849,624 Earl Hilliard, Jr. 849,624 Sigfredo Rubio 849,624 Lashunda Scales 849,624 James Box Spearman 849,624 Patricia Todd 849,624 Sheila Tyson 849,624 Ralph Marion Young, Jr. 849,624 ALABAMA REPUBLICAN PARTY Electors pledged to Donald J. Trump and Michael R. Pence: Name Votes received Dennis H. Beavers 1,441,170 John Wahl 1,441,170 Jacquelyn Gay 1,441,170 Jeana S. Boggs 1,441,170 Joseph R. Fuller 1,441,170 John H. Killian 1,441,170 J. Elbert Peters 1,441,170 Joan Reynolds 1,441,170 Rick Pate 1,441,170 INDEPENDENT CANDIDATES Electors pledged to Jo Jorgensen and Jeremy "Spike" Cohen: Name Votes received Pascal Bruijn 25,176 Lorelei Koory 25,176 Shane A. Taylor 25,176 Jason Matthew Shelby 25,176 Elijah J. Boyd 25,176 Dennis J. Knizley 25,176 Laura Chancey Lane 25,176 Anthony G. Peebles 25,176 Franklin R. -

2021 Legislative Update Week 6

2021 Legislative Update: Week 6 Overview For the first time since the session began on February 2, the Legislature met for two legislative days this week. As of this writing, representatives and senators have met for 14 legislative days out of a possible 30 and will return next week for two more legislative days before a planned one-week Spring Break. While the time spent in the House and Senate Chambers may have been less than usual, the week started with a surprise and included plenty of work in committee and on the floor. Gaming Bills As promised, Senate Bill 214, the comprehensive gaming bill introduced by Sen. Del Marsh of Anniston, made its return to the Senate floor on Tuesday. Behind the scenes, the legislation had been the subject of much discussion between proponents and politicos over the past few weeks, with much of the conversation focusing on where casinos would be located and how new tax revenues would be distributed. But after a lengthy debate on the Senate floor, which included the adoption of several amendments, including one that increased the number of casinos to 10, Marsh’s legislation fell two votes shy of what was needed for passage. The final vote was 19-13, but since the bill was a proposed constitutional amendment, a total of 21 votes were necessary. Importantly, two Senators, Sen. Priscilla Dunn of Bessemer and Sen. Malika Sanders-Fortier of Selma, were absent due to health reasons, and a vacancy exists in one Senate district, District 14, due to former Sen. Cam Ward’s appointment as Director of the Board of Pardons and Paroles. -

Supreme Court of the United States ------♦

No. 02-1580 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- RICHARD VIETH, et al., Appellants, v. ROBERT C. JUBELIRER, et al., Appellees. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Middle District Of Pennsylvania --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LEADERSHIP OF THE ALABAMA SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES: LOWELL BARRON, JEFF ENFINGER, VIVIAN DAVIS FIGURES, RODGER SMITHERMAN, SETH HAMMETT, DEMETRIUS NEWTON, AND KEN GUIN IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JAMES U. BLACKSHER Counsel of Record 710 Title Bldg., 300 North Richard Arrington, Jr., Blvd. Birmingham, Alabama 35203-3352 (205) 322-1100 ROBERT D. SEGALL COPELAND, FRANCO, SCREWS & GILL, P.A. 444 South Perry Street Post Office Box 347 Montgomery, Alabama 36101-0347 (334) 834-1180 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Interest of Amici Curiae ............................................. 1 Summary of Argument ............................................... 3 Argument.................................................................... 6 I. THE FACTS IN ALABAMA: THE LONG JOURNEY FROM SLAVERY AND JIM CROW TO AFRICAN AMERICANS’ EFFECTIVE -

Call to Action

Friday, February 29, 2008 CALL TO ACTION Turn Up Heat on Lawmakers; Tell Them and Us Why We Say ‘NO!’ SB 8 Workers’ Comp Rew rite Blatant Attack on Business SB 15 SB 70 Y our Alabama Retail Association along with more than 20 SB 139 business groups, this week fired back at those advancing SB 221 the most blatant attack on business in the history of SB 229 Alabama. In last week’s Capitol Retail Report , we told you SB 237 about the introduction of five bills that rewrite Alabama’s SB 341 SB 375 Workers’ Compensation Act. This trial-lawyer inspired SB 389 package would single-handily destroy the economic SB 399 progress we’ve worked hard for in our state, encourage an SB 403 avalanche of litigation against Alabama businesses and SB 405 push workers’ comp premiums out of reach for many SB 414 SB 463 businesses. Businesses big and small would feel the pain. HB 67 HB 73 Unlike workers’ compensation reform in other states, this HB 274 package does nothing to cut workers’ compensation costs HB 286 and piles expenses on employers. The big beneficiaries? HB 335 You guessed it – money-hungry trial lawyers. HB 375 HB 472 “This is the worst legislation HB 502 introduced in my almost 20 HB 503 HB 576 years of legislative HB 577 experience,” said ARA President Rick Brown. The issue has united the business community in a way that rivals the collective push for tort reform in Alabama. Bill to ban public We must STOP this legislation. This week, leaders of indoor smoking takes step in state business groups met with legislative leaders to tell them Senate why we cannot go back to the days of workers’ comp abuse, Lawmaker pitches off-the-chart premium increases and out-of-control litigation. -

What Will It Take to Make Alabama's

TABLE OF CONTENTS BCA Information Building The Best Business Climate 02 A Letter to Alabama Businesses 18 BCA's ProgressPac: Elect, Defend, Defeat, and Recruit 04 2017 Legislative Action Summary 20 Education: A Better Workforce Starts in the Classroom 05 Why Invest in BCA? 22 Infrastructure: Alabama's Arteries of Commerce 06 National Partnerships 24 Manufacturing: Building the State's Economy 07 State Partnerships 26 Labor and Employment: Alabama's Vibrant and Productive 08 BCA 2018 Board of Directors Workforce is No Accident 10 BCA Professional Team 28 Judicial and Legal Reform: Fairness and Efficiency 11 BCA Leadership for all Alabamians 12 Alabama Legislators 29 Environment and Energy: A Healthy Environment is 14 Federal Affairs Good for Business 16 BCA 2018 Events Calendar 30 Health Care: Alabama can Lead the Nation We represent more than 1 million 31 Tax and Fiscal Policy: Fairness and Consistency are Keys to Growth 32 Small Business: The Economic Engine of Alabama working Alabamians and their ability to provide for themselves, their families, and their communities. 1 PERSPECTIVE'18 education and works to serve students and parents. We work to ensure that students receive the appropriate education and skill-training and we look forward to working with the Legislature to accomplish a fair and equitable business environment that includes sound education policies. By working together, Alabama's business community and health care community, including physicians, nurses, hospitals, nursing homes, insurance carriers, and other health care providers and professionals, can inform each other and policy makers about how best to solve the problems facing those who access the health care system and marketplace. -

Norfolk Southern Corporation Contributions to Candidates and Political Committees January 1 ‐ December 31, 2017*

NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2017* STATE RECIPIENT OF CORPORATE POLITICAL FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE LA John Bel Edwards$ 4,000 2/6/2017 Primary 2019 Governor DE DE Dem Party (State Acct)$ 1,000 3/1/2017 Election Cycle 2018 State Party Cmte DE DE Rep Party (State Acct)$ 1,000 3/1/2017 Election Cycle 2018 State Party Cmte US Democratic Governors Association (DGA)$ 10,000 3/1/2017 N/A 2017 Association DE Earl Jaques$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House DE Edward Osienski$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House SC Henry McMaster$ 1,000 3/1/2017 Primary 2018 Governor DE James Johnson$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House DE John Kowalko$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House DE John Viola$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House DE Margaret Rose Henry$ 300 3/1/2017 Primary 2018 State Senate DE Mike Mulrooney$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House DE Nicole Poore$ 300 3/1/2017 Primary 2020 State Senate US Republican Governors Association (RGA)$ 10,000 3/1/2017 N/A 2017 Association SC SC Rep House Caucus/Cmte$ 3,500 3/1/2017 N/A 2017 State Party Cmte SC SC Rep Senate Caucus$ 3,500 3/1/2017 N/A 2017 State Party Cmte DE SENR PAC$ 300 3/1/2017 N/A 2017 State PAC DE Stephanie Hansen$ 300 3/1/2017 Primary 2018 State Senate DE Valerie Longhurst$ 300 3/1/2017 General 2018 State House AL AL Rep House Caucus$ 1,500 3/24/2017 N/A 2017 State Party Cmte MS Percy Bland$ 250 4/26/2017 General 2017 Mayor SC SC Dem House Caucus/Cmte$ 1,000 4/26/2017 N/A 2017 -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama Northern Division

Case 2:12-cv-00691-WKW-MHT-WHP Document 203 Filed 12/20/13 Page 1 of 173 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA NORTHERN DIVISION ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE ) BLACK CAUCUS, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) CASE NO. 2:12-CV-691 v. ) (Three-Judge Court) ) THE STATE OF ALABAMA, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________ ) ) ALABAMA DEMOCRATIC ) CONFERENCE, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) CASE NO. 2:12-CV-1081 v. ) (Three-Judge Court) ) THE STATE OF ALABAMA, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Before PRYOR, Circuit Judge, WATKINS, Chief District Judge, and THOMPSON, District Judge. PRYOR, Circuit Judge: “There’s no perfect reapportionment plan. A reapportionment plan depends on what the drafter wants to get, and he can draw them many, many, many ways.” Dr. Joe Reed, Chairman, Alabama Democratic Conference. (Trial Tr. vol. 2, 155, Aug. 9, 2013). Case 2:12-cv-00691-WKW-MHT-WHP Document 203 Filed 12/20/13 Page 2 of 173 The Constitution of Alabama of 1901 requires the Alabama Legislature to redistrict itself following each decennial census of the United States, Ala. Const. Art. IX, §§ 199–200, but for a half century—from 1911 to 1961—the Legislature failed to fulfill that duty. Then the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that this abdication could be tolerated no longer, and it affirmed the judgment of this Court that the Alabama Legislature had to be apportioned after each census based on the principle of one person, one vote. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 568, 586, 84 S. Ct. 1362, 1385, 1394 (1964). -

Legislative Roster Legislative Roster

66064 ARA roster_ARA Legislative Roster 0211 1/13/14 9:49 AM Page 1 SENATE Officers & Committees HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Officers & Committees Kay Ivey . Lt. Governor and President of the Senate Craig Ford . Minority Leader Del Marsh . President Pro Tem Mike Hubbard. Speaker of the House Jabo Waggoner . Majority Leader Victor Gaston. Speaker Pro Tem Alvin Holmes . Dean of the House Vivian Figures. Minority Leader Micky Hammon . Majority Leader Clerks and their phone #s listed with committees. Unless otherwise noted, phone numbers begin with (334) 242- Clerks and their phone #s listed with committees. All phone numbers begin with (334) 242- RULES Maggie Harmon, 7673 INSURANCE TRANSPORTATION, UTILITIES EDUCATION POLICY Karen Cheeks, 7621 2014 RULES FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY & ACCOUNTABILITY 2014 qMcCutcheon, Chairperson Tracey Arnold, (334) 353-0995 & INFRASTRUCTURE qMcClurkin, Chair qP. Williams, Vice Chair qWaggoner, Chairperson Sue Spears, 7853 qWilliams, Chairperson Sabrina Gaston, 7848 qR. Johnson, Vice Chairperson qHill, Chairperson Tracey Arnold, (334) 353-0995 qBlack, Ranking Minority Member qHolley, Vice Chairperson qBussman qColeman qGlover qKeahey qBuskey, Ranking Minority Member qWren, Vice Chairperson qGreer, Chairperson qBeech qButtram qCollins qHenry qBeasonqBedford qBussman qDial qMarsh qScofield qTaylor qBoyd qFord qGaston qGreer qHarper qMcAdory, Ranking Minority Member qGaston, Vice Chair person qJackson qMitchell qRich qVance qDunn qFigures qGlover qIrons LegislativeLegislative JOB CREATION & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT qJones qLaird