Gamma-Rays from the Pulsar Wind Nebulae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pos(BASH 2013)009 † ∗ [email protected] Speaker

The Progenitor Systems and Explosion Mechanisms of Supernovae PoS(BASH 2013)009 Dan Milisavljevic∗ † Harvard University E-mail: [email protected] Supernovae are among the most powerful explosions in the universe. They affect the energy balance, global structure, and chemical make-up of galaxies, they produce neutron stars, black holes, and some gamma-ray bursts, and they have been used as cosmological yardsticks to detect the accelerating expansion of the universe. Fundamental properties of these cosmic engines, however, remain uncertain. In this review we discuss the progress made over the last two decades in understanding supernova progenitor systems and explosion mechanisms. We also comment on anticipated future directions of research and highlight alternative methods of investigation using young supernova remnants. Frank N. Bash Symposium 2013: New Horizons in Astronomy October 6-8, 2013 Austin, Texas ∗Speaker. †Many thanks to R. Fesen, A. Soderberg, R. Margutti, J. Parrent, and L. Mason for helpful discussions and support during the preparation of this manuscript. c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. http://pos.sissa.it/ Supernova Progenitor Systems and Explosion Mechanisms Dan Milisavljevic PoS(BASH 2013)009 Figure 1: Left: Hubble Space Telescope image of the Crab Nebula as observed in the optical. This is the remnant of the original explosion of SN 1054. Credit: NASA/ESA/J.Hester/A.Loll. Right: Multi- wavelength composite image of Tycho’s supernova remnant. This is associated with the explosion of SN 1572. Credit NASA/CXC/SAO (X-ray); NASA/JPL-Caltech (Infrared); MPIA/Calar Alto/Krause et al. -

16Th HEAD Meeting Session Table of Contents

16th HEAD Meeting Sun Valley, Idaho – August, 2017 Meeting Abstracts Session Table of Contents 99 – Public Talk - Revealing the Hidden, High Energy Sun, 204 – Mid-Career Prize Talk - X-ray Winds from Black Rachel Osten Holes, Jon Miller 100 – Solar/Stellar Compact I 205 – ISM & Galaxies 101 – AGN in Dwarf Galaxies 206 – First Results from NICER: X-ray Astrophysics from 102 – High-Energy and Multiwavelength Polarimetry: the International Space Station Current Status and New Frontiers 300 – Black Holes Across the Mass Spectrum 103 – Missions & Instruments Poster Session 301 – The Future of Spectral-Timing of Compact Objects 104 – First Results from NICER: X-ray Astrophysics from 302 – Synergies with the Millihertz Gravitational Wave the International Space Station Poster Session Universe 105 – Galaxy Clusters and Cosmology Poster Session 303 – Dissertation Prize Talk - Stellar Death by Black 106 – AGN Poster Session Hole: How Tidal Disruption Events Unveil the High 107 – ISM & Galaxies Poster Session Energy Universe, Eric Coughlin 108 – Stellar Compact Poster Session 304 – Missions & Instruments 109 – Black Holes, Neutron Stars and ULX Sources Poster 305 – SNR/GRB/Gravitational Waves Session 306 – Cosmic Ray Feedback: From Supernova Remnants 110 – Supernovae and Particle Acceleration Poster Session to Galaxy Clusters 111 – Electromagnetic & Gravitational Transients Poster 307 – Diagnosing Astrophysics of Collisional Plasmas - A Session Joint HEAD/LAD Session 112 – Physics of Hot Plasmas Poster Session 400 – Solar/Stellar Compact II 113 -

Blasts from the Past Historic Supernovas

BLASTS from the PAST: Historic Supernovas 185 386 393 1006 1054 1181 1572 1604 1680 RCW 86 G11.2-0.3 G347.3-0.5 SN 1006 Crab Nebula 3C58 Tycho’s SNR Kepler’s SNR Cassiopeia A Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European? Arabic, European Arabic, Native American? Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Probable Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Distance Estimate: 8,200 light years Distance Estimate: 16,000 light years Distance Estimate: 3,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,500 light years Distance Estimate: 13,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,000 light years Distance Estimate: 6,000 light years Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Core collapse of massive star NASA’s ChANdrA X-rAy ObServAtOry historic supernovas chandra x-ray observatory Every 50 years or so, a star in our Since supernovas are relatively rare events in the Milky historic supernovas that occurred in our galaxy. Eight of the trine of the incorruptibility of the stars, and set the stage for observed around 1671 AD. -

FY13 High-Level Deliverables

National Optical Astronomy Observatory Fiscal Year Annual Report for FY 2013 (1 October 2012 – 30 September 2013) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Pursuant to Cooperative Support Agreement No. AST-0950945 13 December 2013 Revised 18 September 2014 Contents NOAO MISSION PROFILE .................................................................................................... 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 2 2 NOAO ACCOMPLISHMENTS ....................................................................................... 4 2.1 Achievements ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Status of Vision and Goals ................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Status of FY13 High-Level Deliverables ............................................ 5 2.2.2 FY13 Planned vs. Actual Spending and Revenues .............................. 8 2.3 Challenges and Their Impacts ............................................................................ 9 3 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS .............................................................. 11 3.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory ....................................................... 11 3.2 Kitt Peak National Observatory ....................................................................... 14 3.3 Gemini Observatory ........................................................................................ -

The Radio Spectral Index of the Vela Supernova Remnant

A&A 372, 636–643 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010509 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics The radio spectral index of the Vela supernova remnant H. Alvarez1, J. Aparici1,J.May1,andP.Reich2 1 Departamento de Astronom´ıa, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 36-D, Santiago, Chile 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany Received 25 October 2000 / Accepted 9 March 2001 Abstract. We have calculated the integrated flux densities of the different components of the Vela SNR between 30 and 8400 MHz. The calculations were done using the original brightness temperature maps found in the literature, a uniform criterion to select the background temperature, and a unique method to compute the integrated flux density. We have succeeded in obtaining separately, and for the first time, the spectrum of Vela Y and Vela Z. The index of the flux density spectrum of Vela X,VelaY and Vela Z are −0.39, −0.70 and −0.81, respectively. We also present a map of brightness temperature spectral index over the region, between 408 and 2417 MHz. This shows a circular structure in which the spectrum steepens from the centre (Vela X) towards the periphery (Vela Y and Vela Z). X-ray observations show also a circular structure. We compare our spectral indices with those previously published. Key words. ISM: supernova remnants – ISM: Vela X – radio continuum: ISM 1. Introduction between the indices of X and YZ(α ∼−0.35) so that the whole Vela SNR belongs to the shell type. Weiler et al., Radio continuum maps of the Vela SNR area show a com- on the other hand, sustain that YZ has a spectrum con- plex structure. -

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 Abell 35 (Sharpless 2-313) (planetary nebula), 10:70 Abell 85 (supernova remnant), 8:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 11:56 Abell 1689 (galaxy cluster), 3:23 Abell 2218 (galaxy cluster), 11:68 Abell 2744 (Pandora's Cluster) (galaxy cluster), 10:20 Abell catalog planetary nebulae, 6:50–53 Acheron Fossae (feature on Mars), 11:36 Adirondack Astronomy Retreat, 5:16 Adobe Photoshop software, 6:64 AKATSUKI orbiter, 4:19 AL (Astronomical League), 7:17, 8:50–51 albedo, 8:12 Alexhelios (moon of 216 Kleopatra), 6:18 Altair (star), 9:15 amateur astronomy change in construction of portable telescopes, 1:70–73 discovery of asteroids, 12:56–60 ten tips for, 1:68–69 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 American Astronomical Society decadal survey recommendations, 7:16 Lancelot M. Berkeley-New York Community Trust Prize for Meritorious Work in Astronomy, 3:19 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) image of, 11:26 stellar disks, 6:19 Antarctica, astronomical research in, 10:44–48 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 11:32, 56 antimatter, 8:24–29 Antu Telescope, 11:37 APM 08279+5255 (quasar), 11:18 arcminutes, 10:51 arcseconds, 10:51 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 6:19 Arp 188 (Tadpole Galaxy), 11:30 Arp 273 (galaxy pair), 11:65 Arp 299 (NGC 3690) (galaxy pair), 10:55–57 ARTEMIS spacecraft, 11:17 asteroid belt, origin of, 8:55 asteroids See also names of specific asteroids amateur discovery of, 12:62–63 -

Science Highlights

>>> SCIENCENOAO/NSO HIGHLIGHTS Echoes of Galactic Supernovae Armin Rest (Harvard University) & Chris Smith (NOAO) for the Echoes of Historical Supernovae (EHS) Team ight echoes from ancient supernova offer a unique and powerful oppor- tunity to study supernovae and their Lrelationships to supernova remnants (SNRs), as well as interstellar dust and Galactic structure. The use of this relatively simple phenomenon of light echoes in such studies is just now developing into an exciting new field of study. This is one of the very rare occasions in astronomy that the cause and effect of the same astronomical event can be observed, in that we can study the physics of the SNR as it appears now and also the physics of the explosion that produced it hundreds of years ago. We define a light echo as reflected light from a light source, not reprocessed light. Similar to the muffled echo of sound when someone shouts something toward a wall, the light echo still contains the initial signature of the original light, even if the precise signa- ture is somewhat modified by details of the reflecting surface. Since the reflected light traverses a longer path than the light that takes the direct path to the observer, it will be Figure 1 observed some time after the initial explosion is observed. to the SNR may be tens of times larger than if the Galactic plane than the supernovae in the the same SN and reflecting dust were located expectation that dust would be more highly Our group pioneered the optical discovery in the LMC. Thus the search annuli for light concentrated there. -

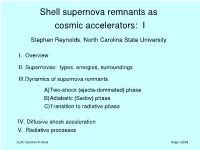

Shell Supernova Remnants As Cosmic Accelerators: I Stephen Reynolds, North Carolina State University

Shell supernova remnants as cosmic accelerators: I Stephen Reynolds, North Carolina State University I. Overview II. Supernovae: types, energies, surroundings III.Dynamics of supernova remnants A)Two-shock (ejecta-dominated) phase B)Adiabatic (Sedov) phase C)Transition to radiative phase IV. Diffusive shock acceleration V. Radiative processes SLAC Summer Institute August 2008 Supernova remnants for non-astronomers Here: ªSNRº means gaseous shell supernova remnant. Exploding stars can also leave ªcompact remnants:º -- neutron stars (which may or may not be pulsars) -- black holes We exclude pulsar-powered phenomena (ªpulsar-wind nebulae,º ªCrablike supernova remnantsº after the Crab Nebula) SN ejects 1 ± 10 solar masses (M⊙) at high speed into surrounding material, heating to X-ray emitting temperatures (> 107 K). Expansion slows over ~105 yr. Young (ªadiabatic phaseº) SNRs: t < tcool ~ 10,000 yr. Observable primarily through radio (synchrotron), X-rays (if not absorbed by intervening ISM) Older (ªradiative phaseº): shocks are slow, highly compressive; bright optical emission. (Still radio emitters, maybe faint soft X-rays). SLAC Summer Institute August 2008 SNRs: background II Supernovae: visible across Universe for weeks ~ months SNRs: detectable only in nearest galaxies, but observable for 104 ± 105 yr So: almost disjoint sets. Important exception: Historical supernovae. Chinese, European records document ªnew starsº visible with naked eye for months. In last two millenia: 185 CE, 386, 393, 1006, 1054 (Crab Nebula), 1181 (?), 1572 (Tycho©s SN), 1604 (Kepler©s SN) ªQuasi-historical:º deduced to be < 2000 yr old, but not seen due to obscuration: Cas A (~ 1680), G1.9+0.3 (~ 1900). Unique testbed: SN 1987A (Large Magellanic Cloud) SLAC Summer Institute August 2008 A supernova-remnant gallery 1. -

Supernova Remnants: the X-Ray Perspective

Astron Astrophys Rev (2012) 20:49 DOI 10.1007/s00159-011-0049-1 Supernova remnants: the X-ray perspective Jacco Vink Published online: 8 December 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Supernova remnants are beautiful astronomical objects that are also of high scientific interest, because they provide insights into supernova explosion mecha- nisms, and because they are the likely sources of Galactic cosmic rays. X-ray obser- vations are an important means to study these objects. And in particular the advances made in X-ray imaging spectroscopy over the last two decades has greatly increased our knowledge about supernova remnants. It has made it possible to map the prod- ucts of fresh nucleosynthesis, and resulted in the identification of regions near shock fronts that emit X-ray synchrotron radiation. Since X-ray synchrotron radiation re- quires 10–100 TeV electrons, which lose their energies rapidly, the study of X-ray synchrotron radiation has revealed those regions where active and rapid particle ac- celeration is taking place. In this text all the relevant aspects of X-ray emission from supernova remnants are reviewed and put into the context of supernova explosion properties and the physics and evolution of supernova remnants. The first half of this review has a more tutorial style and discusses the basics of supernova remnant physics and X-ray spectroscopy of the hot plasmas they contain. This includes hydrodynamics, shock heating, thermal conduction, radiation processes, non-equilibrium ionization, He-like ion triplet lines, and cosmic ray acceleration. The second half offers a review of the advances made in field of X-ray spectroscopy of supernova remnants during the last 15 year. -

Neutron Star

Explosive end of a star (masses M > 8 M⊙ ) Death of massive stars M > 8 M⊙ nuclear reactions stop at Fe ⟹ contraction continues to T = 1010 K (e− degenerate gas cannot support the star for core mass Mcore > 1.4 M⊙ ) ⟹ Fe photo-disintegration (production of α particles, neutrons, protons) ⟹ energy absorbed, contraction goes faster, density grows to point when: e− + p → n + νe ⟹ e− are removed support of e− degenerate gas drops ⟹ collapse continues 12 17 3 T = 10 K, core density 3×10 kg / m ⟹ neutron degeneracy pressure ⟹ collapse suddenly stops ⟹ matter falling inward at high high speed matter bounces when core reached ⟹ shock front outwards ⟹ STAR EXPLODES (SUPERNOVA) ⟹ STAR EXPLODES (SUPERNOVA) Not clear what happens, some or all of the following processes: • Shock wave blows apart outer layer, mainly light elements • Shock wave heats gas to T = 1010 K ⟹ explosive nuclear reactions ⟹ fusion produce Fe-peak elements ⟹ outer layer blown apart • Enormous amount of neutrinos formed. Most escape without interaction, some lift off mass in outer layer External envelope falling inwards at speed up to v ~ 70,000 km/s Bounce backward when core reached → Shock front outward Star destroyed by explosion Stellar explosion = supernova (computer simulation) Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xVk48Nyd4zY Final result of core collapse: neutron star Supernova remnant: Crab Nebula Distance: 6500 light years Explosion seen in 1054 Size of the bubble: ~ 10 pc Final result of core collapse: neutron star Supernova remnant: Crab Nebula Distance: 6500 light -

Pulsar Wind Nebulae in Evolved Supernova Remnants John M

THE ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL, 563:806È815, 2001 December 20 V ( 2001. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. PULSAR WIND NEBULAE IN EVOLVED SUPERNOVA REMNANTS JOHN M. BLONDIN Department of Physics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 ROGER A. CHEVALIER Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, P.O. Box 3818, Charlottesville, VA 22903 AND DARGAN M. FRIERSON Department of Mathematics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Received 2001 July 4; accepted 2001 August 27 ABSTRACT For pulsars similar to the one in the Crab Nebula, most of the energy input to the surrounding wind nebula occurs on a timescale[103 yr; during this time, the nebula expands into freely expanding super- nova ejecta. On a timescale D104 yr, the interaction of the supernova with the surrounding medium drives a reverse shock front toward the center of the remnant, where it crushes the pulsar wind nebula (PWN). We have carried out one- and two-dimensional, two-Ñuid simulations of the crushing and reex- pansion phases of a PWN. We show that (1) these phases are subject to Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities that result in the mixing of thermal and nonthermal Ñuids, and (2) asymmetries in the surrounding inter- stellar medium give rise to asymmetries in the position of the PWN relative to the pulsar and explosion site. These e†ects are expected to be observable in the radio emission from evolved PWN because of the long lifetimes of radio-emitting electrons. The scenario can explain the chaotic and asymmetric appear- ance of the Vela X PWN relative to the Vela pulsar without recourse to a directed Ñow from the vicinity of the pulsar. -

Nature's Biggest Explosions: Past, Present, and Future

Nature’s Biggest Explosions: Past, Present, and Future Edo Berger Harvard University Why Study Cosmic Explosions? Why Study Cosmic Explosions? Why Study Cosmic Explosions? Why Study Cosmic Explosions? Why Study Cosmic Explosions? The Past About 10 “guest stars” have been mentioned in historical records, spanning from 185 to 1604 AD. All were observed with the naked eye (first telescope was built in 1608 AD). “Throughout all past time, according to the records handed down from generation to generation, nothing is observed to have changed either in the whole of the outermost heaven or in any of its proper parts.” Aristotle, De caelo (On the Heavens), 350 BC SN 185 In 185 AD Chinese records mark the appearance of a “guest star” which remained visible for 8 months and did not move like a planet or a comet. This is the oldest record of a supernova. “In the 2nd year of the epoch Zhongping, the 10th month, on the day Kwei Hae, a strange star appeared in the middle of Nan Mun … In the 6th month of the succeeding year it disappeared.” SN 1006 On April 1006 records from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia mark the appearance of the brightest “guest star” ever seen: bright as a quarter moon and visible during the day. It remained visible for almost 2 years. “…spectacle was a large circular body, 2½ to 3 times as large as Venus. The sky was shining because of its light. The intensity of its light was a little more than the light of the Moon when one-quarter illuminated" SN 1054 On July 4, 1054 AD records from the Middle East and Asia (and potentially North America) mark the appearance of a bright “guest star”; as bright as a 1/16 moon and remained visible for 2 years.