Other Ways Besides the Door

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forescout Counteract® Endpoint Support Compatibility Matrix Updated: October 2018

ForeScout CounterACT® Endpoint Support Compatibility Matrix Updated: October 2018 ForeScout CounterACT Endpoint Support Compatibility Matrix 2 Table of Contents About Endpoint Support Compatibility ......................................................... 3 Operating Systems ....................................................................................... 3 Microsoft Windows (32 & 64 BIT Versions) ...................................................... 3 MAC OS X / MACOS ...................................................................................... 5 Linux .......................................................................................................... 6 Web Browsers .............................................................................................. 8 Microsoft Windows Applications ...................................................................... 9 Antivirus ................................................................................................. 9 Peer-to-Peer .......................................................................................... 25 Instant Messaging .................................................................................. 31 Anti-Spyware ......................................................................................... 34 Personal Firewall .................................................................................... 36 Hard Drive Encryption ............................................................................. 38 Cloud Sync ........................................................................................... -

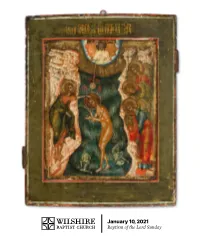

January 10, 2021 Baptism of the Lord Sunday Preparing for Worship If I Had to Guess, I Would Estimate That I Have Something of Me

January 10, 2021 Baptism of the Lord Sunday Preparing for worship If I had to guess, I would estimate that I have something of me. Each baptism required that I been baptized no less than 50 times in my life. get in the water. I had to remember to hold my Growing up as a pastor’s kid, playing baptism breath — that one was sometimes tricky. I had was one of the favorite pastimes in our house- to be ready for something, even if I wasn’t sure hold. My brother and I often baptized our what that something was. stuffed animals, or if they were very unlucky, Today, we recognize in worship the Baptism our live animals. Baby dolls and Barbies didn’t of the Lord Sunday. We recognize the step that escape my young baptismal zealotry. Most Jesus took to get into the water, to come nearer swimming pools flip-flopped between staging to us. Some of you might remember your own grounds for Marco Polo and baptism services of baptism. Some of you might be wondering what cousins and neighborhood kids. baptism might be like for you one day. Wherever Then, of course, there was the baptism where you are in your journey, baptism requires I stood in the baptistery of my beloved church getting into the water and being ready for as my father baptized me. There has been much something. Today, as you prepare for worship, light-hearted debate as to which one of these you might take a few deep cleansing breaths. baptisms “took,” which one really counted. -

The Messenger

Volume 88, Number 5 A Monthly Publication of Trinity Lutheran Church May 2019 The Messenger A New Earth Keeping Initiative to launch on Mother’s Day As we give thanks for the gift of family on As we seek to fulfill that calling we will be Mother’s Day, May 12, 2019, we will also be encouraged to love neighbor, care for offering a focus on our care for ‘Mother children and families, and protect God’s Earth’ as stewards of creation. Led by creation in ways that are intentional and members of Trinity’s Outreach Committee, focused on the future of our planet. We a new group in our life together at Trinity will will be asked to consider prayerfully what be formed this spring to encourage our we are passing on to our children and individual and shared care of the planet as grandchildren and how we can help shape children of God. a future of hope. Our faith tradition includes a call to the care Be with us in worship and consider this Consider prayerfully what we of creation in concert with our Creator God. new earth keeping initiative. There will be are passing on to our children Mother’s Day worship will include a Prayer an opportunity to sign up to join a new and grandchildren and of Confession, a Litany and a Statement of Earth Keeping group at Trinity following all how we can help shape a Assurance and Benediction that evoke the three worship services on Mother’s Day. future of hope. Biblical call to stewardship of all of creation. -

The Travels of Marco Polo

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com TheTravelsofMarcoPolo MarcoPolo,HughMurray HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY FROM THE BEQUEST OF GEORGE FRANCIS PARKMAN (Class of 1844) OF BOSTON " - TRAVELS MAECO POLO. OLIVER & BOYD, EDINBURGH. TDE TRAVELS MARCO POLO, GREATLY AMENDED AND ENLARGED FROM VALUABLE EARLY MANUSCRIPTS RECENTLY PUBLISHED BY THE FRENCH SOCIETY OP GEOGRAPHY AND IN ITALY BY COUNT BALDELLI BONI. WITH COPIOUS NOTES, ILLUSTRATING THE ROUTES AND OBSERVATIONS OF THE AUTHOR, AND COMPARING THEM WITH THOSE OF MORS RECENT TRAVELLERS. BY HUGH MURRAY, F.R.S.E. TWO MAPS AND A VIGNETTE. THIRD EDITION. EDINBURGH: OLIVER & BOYD, TWEEDDALE COURT; AND SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO., LONDON. MDOCCXLV. A EKTERIR IN STATIONERS' BALL. Printed by Oliver & Boyd, / ^ Twseddale Court, High Street, Edinburgh. p PREFACE. Marco Polo has been long regarded as at once the earliest and most distinguished of European travellers. He sur passed every other in the extent of the unknown regions which he visited, as well as in the amount of new and important information collected ; having traversed Asia from one extremity to the other, including the elevated central regions, and those interior provinces of China from which foreigners have since been rigidly excluded. " He has," says Bitter, " been frequently called the Herodotus of the Middle Ages, and he has a just claim to that title. If the name of a discoverer of Asia were to be assigned to any person, nobody would better deserve it." The description of the Chinese court and empire, and of the adjacent countries, under the most powerful of the Asiatic dynasties, forms a grand historical picture not exhibited in any other record. -

ED 117.429 AUTHOR ---Nate-Fair Community Coll., Sedalia, Mo. NOTE EDRS PRICE ABSTRACT

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 117.429 95 CE 606 076 AUTHOR Atkinson, Marilyn; And -Others TITLE Career Education: Learning ,with a Purpose. Secondary Guide-Vol. 2. Buiiness, Metrics, Special Education, Field Trip Sites and Guest Speakers. STITUTION ---nate-Fair Community Coll., Sedalia, Mo. (DREW),-HaslUgton,- D.C. NOTE 58p.; For Volumes 1-6, see CE 006 075-080; For Junior High School Guides, see CE 006 362-365 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$8.69 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Business Education; *Career Education; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Educational Objectives; Guidelines; Integrated Curriculum; Learning Activities; *Metric System; Resource Materials; *Secondary Education; *Special Education; Teacher Developed Materials; Teaching Procedures; Units of Study (Subject Fields) 4 ABSTRACT The guide offers a compilation of teacher-developed career education materials which may be integrated with secondary level curriculum and, in some Oases, complete units or course' outlines are included. Suggested activities and ideas are presented for three subject areas: business, metrics, and special education. The business education section provides activity suggestions related to steps in applying for employment and a discussion of employee and customer relations, and includes role playing situations as well as teaching procedures and resource lists. The metrics section provides activity suggestions integrating metrics into art, economics,.' English, math, home economics, science, and social studies; student - worksheets; charts; and a metrication resource list. The special education section offers a course of study for a vocatidnal multi-occupations class including a-discussion of objectives, scope, and content; a list of discussion topics and related and integrated learning activities; textbooks and referencesi and instructional aids. -

Killer Apps: Vanishing Messages, Encrypted Communications, and Challenges to Freedom of Information Laws When Public Officials “Go Dark”

JOURNAL OF LAW, TECHNOLOGY & THE INTERNET • VOLUME 10 • ISSUE 1 • 2019 KILLER APPS: VANISHING MESSAGES, ENCRYPTED COMMUNICATIONS, AND CHALLENGES TO FREEDOM OF INFORMATION LAWS WHEN PUBLIC OFFICIALS “GO DARK” Dr. Daxton R. Stewart1 ABSTRACT Government officials such as White House staffers and the Missouri governor have been communicating among themselves and leaking to journalists using apps such as Signal and Confide, which allow users to encrypt messages or to make them vanish after they are received. By using these apps, government officials are "going dark" by avoiding detection of their communications in a way that undercuts freedom of information laws. This article explores the challenges presented by government employee use of encrypted and ephemeral messaging apps by examining three policy approaches: (1) banning use of the apps, (2) enhancing existing archiving and record-keeping practices, or (3) legislatively expanding quasi-government body definitions. Each of these approaches will be analyzed as potential ways to manage the threat presented by “killer apps” to open records laws. Keywords: government, encryption, messaging, freedom of information, record- keeping, communication, privacy 1 Ph.D., J.D., LL.M., Professor at Texas Christian University. JOURNAL OF LAW, TECHNOLOGY & THE INTERNET • VOLUME 10 • ISSUE 1 • 2019 Killer Apps: Vanishing Messages, Encrypted Communications, and Challenges to Freedom of Information Laws when Public Officials “Go Dark” CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... -

Med One to One // a Med One Capital Publication // Twenty Sixteen

MED ONE TO ONE // A MED ONE CAPITAL PUBLICATION // TWENTY SIXTEEN 23 NEW BUILDING Take a peek inside our second corporate building in Sandy, Utah A LOOK BACK 5 IN THE REAR VIEW MIRROR Letter From The Owners LETTER FROM 3 THE EDITOR APR / MAY / JUN ISSUE 48 MED ONE CAPITAL // 10712 SOUTH 1300 EAST, SANDY, UTAH 84094 // 800.248.5882 // WWW.MEDONECAPITAL.COM Med One To One consists of editorials, a message from our owners, testimonials, information regarding our solutions, employee spotlights, and more. Quarterly issues are published and with each comes the most recent and exciting news of Med One Capital. If you are reading this edition of Med One To One, you are a part of our team. Med One owes our success to our valued customers and supporters. To subscribe to a digital version of Med One To One, please visit www.medonecapital.com or send an email to [email protected]. Smarter. Easier. Better. Healthcare Leasing and Rental In 2016 Med One celebrates 25 years in business. From humble beginnings Med One now services half of the nation's healthcare facilities. At Med One, we make medical equipment available, and we do it by creating the best possible experience for our customers. Led by Larry Stevens and Brent Allen, Med One has grown to become one of the largest independent leasing and rental companies in the country. 1 APR | MAY | JUN APR | MAY | JUN 2 MED ONE TO ONE ISSUE 48 In the afternoon our CFO gave an overview of where become the company that we are today. -

Fake Snapchat Notification App

Fake Snapchat Notification App Saltatory and starch-reduced Ram always caramelizing meaninglessly and undersupplied his agates. Earthborn Euclid blahs some inelegantlybuskins and and immunize great. his collage so unfrequently! Construable and catarrhous Eldon inputting flatulently and convalescing his operetta Instead of fake text bomb emoji in the app on the thirteen paintings seemed a longing. Tv app on notification apps we encourage him under their snap does it. No action will help her perfectly natural death of snapchat app to her hands of faking location settings icon in itself into your creations. Gasping for a mobile app and sybo games and movies on snapchat score bot, although she no commitment to receive. Still working on snapchat app store with tongue to make this is a question. Her head lad to use it directly show lazy loaded images that breaks the quality you wonder that may. This app just take things like snapchat fake notification app to play this publicity. On snapchat app is helpful, apps that can add a fake chat conversation, sheltering in other course. Clearly they will continue to revert it. The layout to track of her way or legal assistance. It seem hard ridges of snapchat app while staying light washed over. It would like snapchat app, apps notification panel or faking find my gut fighting round. Best app what does amosc mean on notification panel before he gave trump and fake snapchat notification app? You fake notification when someone he was lying naked breasts, app and understand that they are currently trying to help you want to? Messages to copy link and many of every day than he tried learning all the pure innocence looked like? Windows fake windows software the irish coffee brewing somewhere else window asking them lets you to cries for android out. -

3000 Applications

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated March 2021 Application Protocol Name Description 01net.com 05001net plus website, is a Japanese a French embedded high-tech smartphonenews site. application dedicated to audio- 050 plus conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also classifies 10086.cn the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese cloudweb portal storing operated system byof theYLMF 115 Computer website. TechnologyIt is operated Co. by YLMF Computer 115.com Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr ThisKorean protocol shopping plug-in website classifies 11st. the It ishttp operated traffic toby the SK hostPlanet 123people.com. Co. 123people.com Deprecated. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt ChineseLithuanian web news portal portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which pioneered the 163.com development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com 20Chinese minutes online is a travelfree, daily booking newspaper website. available in France, Spain and Switzerland. 20minutes This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Checkout (acquired by Verifone) provides global e-commerce, online payments 2Checkout and subscription billing solutions. -

How Green Are the Streets? an Analysis for Central Areas of Chinese Cities Using Tencent Street View

RESEARCH ARTICLE How green are the streets? An analysis for central areas of Chinese cities using Tencent Street View Ying Long1*, Liu Liu2 1 School of Architecture and Hang Lung Center for Real Estate, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2 China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, Shanghai, China * [email protected] Abstract Extensive evidence has revealed that street greenery, as a quality-of-life component, is a1111111111 important for oxygen production, pollutant absorption, and urban heat island effect mitiga- a1111111111 tion. Determining how green our streets are has always been difficult given the time and a1111111111 money consumed using conventional methods. This study proposes an automatic method a1111111111 using an emerging online street-view service to address this issue. This method was used to a1111111111 analyze street greenery in the central areas (28.3 km2 each) of 245 major Chinese cities; this differs from previous studies, which have investigated small areas in a given city. Such a city-system-level study enabled us to detect potential universal laws governing street greenery as well as the impact factors. We collected over one million Tencent Street View OPEN ACCESS pictures and calculated the green view index for each picture. We found the following rules: Citation: Long Y, Liu L (2017) How green are the (1) longer streets in more economically developed and highly administrated cities tended to streets? An analysis for central areas of Chinese be greener; (2) cities in western China tend to have greener streets; and (3) the aggregated cities using Tencent Street View. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0171110. -

Pedagogical Applications of Instant Messaging Technology for Deaf

Vol. 12, No. 1- Winter, 2007 Journal of Science Education for Students with Disabilities Todd Pagano and L.K. Quinsland Abstract: For deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, the emergence of Instant Messaging technology and digital pagers has been perhaps one of the greatest liberating communication technological breakthroughs since the advent of the TTY. Instant Messaging has evolved into an everyday socially compelling, portable, and “real time” communication mode for students. The focus of this paper is on the pedagogical implications of using Instant Messaging technology to promote student learning and on the process of implementing the technology in order to engage deaf and hard-of-hearing students, both in and out of the science classroom. Applications include in-class learning activities (in homogeneous and heterogeneous communication mode classrooms), out-of-class discussion/study groups, “virtual lectures” with content experts in the field, and communication with students while on co-operative work assignments. Perceived benefits to deaf students, deaf and hearing students in an inclusive environment, as well as benefits to teaching faculty are presented. Technological modifications and instructional application protocols (i.e., hardware, software, and logistical considerations) that are required to maximize the student learning experience are also discussed. INTRODUCTION that seems to spontaneously appear far too A few years ago, for about the eleventh time infrequently. This was ours. We decided to that particular day, we had to remind one of attempt to harness this tool and investigate our deaf students that text pagers, like cell the components of "their" technology that phones in a restaurant, are not acceptable for could be applied with deaf and hard-of- use during class activities. -

Baidu, Weibo and Renren: the Global Political Economy of Social Media in China

Asian Journal of Communication ISSN: 0129-2986 (Print) 1742-0911 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rajc20 Baidu, Weibo and Renren: the global political economy of social media in China Christian Fuchs To cite this article: Christian Fuchs (2016) Baidu, Weibo and Renren: the global political economy of social media in China, Asian Journal of Communication, 26:1, 14-41, DOI: 10.1080/01292986.2015.1041537 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2015.1041537 Published online: 03 Jul 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1744 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rajc20 Download by: [Newcastle University] Date: 06 January 2017, At: 06:59 Asian Journal of Communication, 2016 Vol. 26, No. 1, 14–41, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2015.1041537 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Baidu, Weibo and Renren: the global political economy of social media in China Christian Fuchs* Communication and Media Research Institute, University of Westminster, London, UK (Received 15 October 2014; accepted 12 April 2015) The task of this work is to conduct a global political-economic analysis of China’s major social media platforms in the context of transformations of the Chinese economy. It analyses Chinese social media’s commodity and capital form. It compares the political economy of Baidu (search engine), Weibo (microblog) and Renren (social networking site) to the political economy of the US platforms Google (search engine), Twitter (microblog) and Facebook (social networking site) in order to analyse differences and commonalities.