Opuscula Philolichenum, 6: 1-XXXX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleopsidiumdiscurrens, Comb. Nova, Newly Discovered in Southern Tibet

Ann. Bot. Fennici 33: 231–236 ISSN 0003-3847 Helsinki 30 October 1996 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 1996 Pleopsidium discurrens, comb. nova, newly discovered in southern Tibet (Lichenological results of the Sino-German Joint Expedition to southeastern and eastern Tibet 1994. II.) Walter Obermayer Obermayer, W., Institut für Botanik, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Holteigasse 6, A-8010 Graz, Austria Reveived 30 April 1996, accepted 10 June 1996 Pleopsidium discurrens (Zahlbr.) Obermayer comb. nova, hitherto known only from the type and paratype localities in NW Yunnan and SW Sichuan, has been discovered in SE Tibet. Morphological characters which separate it from other taxa of Pleopsidium Koerber emend. Hafellner, TLC data and ecological notes are provided. A lectotype of Acarospora discurrens Zahlbr. is selected. Key words: Acarospora discurrens, flora of Tibet, lichenized Ascomycotina, Pleopsidium, taxonomy, TLC data INTRODUCTION the genus Acarospora A. Massal. has only cited the taxon in an enumeration of previously described In 1930, the famous Viennese lichenologist Alex- species (Magnusson 1933: 47) and in a key, treating ander Zahlbruckner published a thorough study of taxa described after 1929 (Magnusson 1956: 4). lichens collected mainly by Heinrich Handel-Maz- During a three month expedition to southeast- zetti during an expedition of the Akademie der Wissen- ern and eastern Tibet in the summer of 1994, the schaften in Wien to southwestern China (Zahlbruckner author had the opportunity to make a further collec- 1930). From 850 lichen specimens, Zahlbruckner tion of the mentioned species with its very conspicu- described 256 new taxa, including 219 species and ous growth form (see Figs. -

DISSERTAÇÃO Lidiane Alves Dos Santos.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE MICOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA DE FUNGOS LIDIANE ALVES DOS SANTOS RELAÇÕES FILOGENÉTICAS DOS GÊNEROS LECANORA ACH. E NEOPROTOPARMELIA GARIMA SINGH, LUMBSCH & I. SCHIMITT (LECANORALES, ASCOMYCOTA LIQUENIZADOS) Recife 2019 LIDIANE ALVES DOS SANTOS RELAÇÕES FILOGENÉTICAS DOS GÊNEROS LECANORA ACH. E NEOPROTOPARMELIA GARIMA SINGH, LUMBSCH & I. SCHIMITT (LECANORALES, ASCOMYCOTA LIQUENIZADOS) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biologia de Fungos do Departamento de Micologia do Centro de Biociências da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia de Fungos. Área de Concentração: Micologia Básica Orientadora: Profª. Dra. Marcela Eugenia da Silva Caceres. Coorientador: Dr. Robert Lücking. Recife 2019 Catalogação na fonte Elaine C Barroso (CRB4/1728) Santos, Lidiane Alves dos Relações filogenéticas dos gêneros Lecanora Ach. e Neoprotoparmelia Garima Singh, Lumbsch & I. Schimitt (Lecanorales, Ascomycota Liquenizados) / Lidiane Alves dos Santos- 2019. 52 folhas: il., fig., tab. Orientadora: Marcela Eugênia da Silva Cáceres Coorientador: Robert Lücking Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Centro de Biociências. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia de Fungos. Recife, 2019. Inclui referências 1. Fungos liquenizados 2. Filogenia 3. Metabólitos secundários I. Cáceres, Marcela Eugênia da Silva (orient.) II. Lücking, Robert (coorient.) III. Título 579.5 CDD (22.ed.) UFPE/CB-2019-312 LIDIANE ALVES DOS SANTOS RELAÇÕES FILOGENÉTICAS DOS GÊNEROS LECANORA ACH. E NEOPROTOPARMELIA GARIMA SINGH, LUMBSCH & I. SCHIMITT (LECANORALES, ASCOMYCOTA LIQUENIZADOS) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biologia de Fungos do Departamento de Micologia do Centro de Biociências da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia de Fungos. -

Untangling Quantitative Lichen Diversity in and Around Badrinath Holy Pilgrimage of Western Himalaya, India

Journal of Graphic Era University Vol. 6, Issue 1, 36-46, 2018 ISSN: 0975-1416 (Print), 2456-4281 (Online) Untangling Quantitative Lichen Diversity in and Around Badrinath Holy Pilgrimage of Western Himalaya, India Sugam Gupta1, Omesh Bajpai2*, Himanshu Rai3,4, Dalip Kumar Upreti3, Pradeep Kumar Sharma1, Rajan Kumar Gupta4 1Department of Environmental Science Graphic Era (Deemed to be University), Dehradun, India 2Division of Plant Sciences Plant and Environmental Research Institute (PERI), Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India 3Lichenology laboratory, Plant Diversity, Systematics and Herbarium Division, CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India 4Department of Botany Pt. Lalit Mohan, Government P.G. College, Rishikesh, Dehradun, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Received August 16, 2017; Accepted, December 6, 2017) Abstract The present study was conducted in the Badrinath holy pilgrimage in Western Himalaya. Lichen collected from seven localities (Badrinath, enroute Bhimpul to Vasudhara, Mana, enroute Vasudhara to Mana, Bhimpul, Vasudhara Glacier and enroute Vasudhara to Bhagirathi Glacier). The highest overall IVI (6.64) was recorded for Rhizoplaca chrysoleuca. The maximum number of lichens have been documented in Badrinath locality (139 spp.) while minimum (6) in enroute Vasudhara to Bhagirathi Glacier. The Badrinath has also express maximum 71 site specific species, while the Vasudhara Glacier has only 2 species. The dominance has been computed maximum (0.17) for enroute Vasudhara to Bhagirathi Glacier while, minimum for the Badrinath (0.01). The lowest Simpson Index value (0.83) has been recorded in enroute Vasudhara to Bhagirathi Glacier while the highest (0.99) in Badrinath. The lowest value of Berger-Parker diversity index (0.03), as well as the highest values of Brillouin, Shannon, Menhinick, Margalef and Fisher alpha diversity indices (7.20, 4.78, 8.03, 24.2 and 100.6 respectively) from the Badrinath locality, designates it as a site of highest species diversity. -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

<I> Lecanoromycetes</I> of Lichenicolous Fungi Associated With

Persoonia 39, 2017: 91–117 ISSN (Online) 1878-9080 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.05 Phylogenetic placement within Lecanoromycetes of lichenicolous fungi associated with Cladonia and some other genera R. Pino-Bodas1,2, M.P. Zhurbenko3, S. Stenroos1 Key words Abstract Though most of the lichenicolous fungi belong to the Ascomycetes, their phylogenetic placement based on molecular data is lacking for numerous species. In this study the phylogenetic placement of 19 species of cladoniicolous species lichenicolous fungi was determined using four loci (LSU rDNA, SSU rDNA, ITS rDNA and mtSSU). The phylogenetic Pilocarpaceae analyses revealed that the studied lichenicolous fungi are widespread across the phylogeny of Lecanoromycetes. Protothelenellaceae One species is placed in Acarosporales, Sarcogyne sphaerospora; five species in Dactylosporaceae, Dactylo Scutula cladoniicola spora ahtii, D. deminuta, D. glaucoides, D. parasitica and Dactylospora sp.; four species belong to Lecanorales, Stictidaceae Lichenosticta alcicorniaria, Epicladonia simplex, E. stenospora and Scutula epiblastematica. The genus Epicladonia Stictis cladoniae is polyphyletic and the type E. sandstedei belongs to Leotiomycetes. Phaeopyxis punctum and Bachmanniomyces uncialicola form a well supported clade in the Ostropomycetidae. Epigloea soleiformis is related to Arthrorhaphis and Anzina. Four species are placed in Ostropales, Corticifraga peltigerae, Cryptodiscus epicladonia, C. galaninae and C. cladoniicola -

A Multigene Phylogenetic Synthesis for the Class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 Fungi Representing 1139 Infrageneric Taxa, 317 Genera and 66 Families

A multigene phylogenetic synthesis for the class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 fungi representing 1139 infrageneric taxa, 317 genera and 66 families Miadlikowska, J., Kauff, F., Högnabba, F., Oliver, J. C., Molnár, K., Fraker, E., ... & Stenroos, S. (2014). A multigene phylogenetic synthesis for the class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 fungi representing 1139 infrageneric taxa, 317 genera and 66 families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 79, 132-168. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.003 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.003 Elsevier Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 79 (2014) 132–168 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multigene phylogenetic synthesis for the class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 fungi representing 1139 infrageneric taxa, 317 genera and 66 families ⇑ Jolanta Miadlikowska a, , Frank Kauff b,1, Filip Högnabba c, Jeffrey C. Oliver d,2, Katalin Molnár a,3, Emily Fraker a,4, Ester Gaya a,5, Josef Hafellner e, Valérie Hofstetter a,6, Cécile Gueidan a,7, Mónica A.G. Otálora a,8, Brendan Hodkinson a,9, Martin Kukwa f, Robert Lücking g, Curtis Björk h, Harrie J.M. Sipman i, Ana Rosa Burgaz j, Arne Thell k, Alfredo Passo l, Leena Myllys c, Trevor Goward h, Samantha Fernández-Brime m, Geir Hestmark n, James Lendemer o, H. Thorsten Lumbsch g, Michaela Schmull p, Conrad L. Schoch q, Emmanuël Sérusiaux r, David R. Maddison s, A. Elizabeth Arnold t, François Lutzoni a,10, -

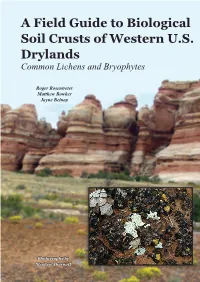

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes Roger Rosentreter Matthew Bowker Jayne Belnap Photographs by Stephen Sharnoff Roger Rosentreter, Ph.D. Bureau of Land Management Idaho State Office 1387 S. Vinnell Way Boise, ID 83709 Matthew Bowker, Ph.D. Center for Environmental Science and Education Northern Arizona University Box 5694 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 Jayne Belnap, Ph.D. U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center Canyonlands Research Station 2290 S. West Resource Blvd. Moab, UT 84532 Design and layout by Tina M. Kister, U.S. Geological Survey, Canyonlands Research Station, 2290 S. West Resource Blvd., Moab, UT 84532 All photos, unless otherwise indicated, copyright © 2007 Stephen Sharnoff, Ste- phen Sharnoff Photography, 2709 10th St., Unit E, Berkeley, CA 94710-2608, www.sharnoffphotos.com/. Rosentreter, R., M. Bowker, and J. Belnap. 2007. A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands. U.S. Government Printing Office, Denver, Colorado. Cover photos: Biological soil crust in Canyonlands National Park, Utah, cour- tesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 4 How to use this guide .................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 Crust composition .................................................................................. -

Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Lichen Genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea

Fungal Diversity Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of the lichen genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea Sérusiaux, E.1*, Goffinet, B.2, Miadlikowska, J.3 and Vitikainen, O.4 1Plant Taxonomy and Conservation Biology Unit, University of Liège, Sart Tilman B22, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 North Eagleville Road, Storrs CT 06269-3043 USA 3Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338, USA 4Botanical Museum (Mycology), P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Sérusiaux, E., Goffinet, B., Miadlikowska, J. and Vitikainen, O. (2009). Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of the the lichen genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea. Fungal Diversity 38: 185-224. The lichen genus Peltigera is represented in Papua New Guinea by 15 species, including 6 described as new for science: P. cichoracea, P. didactyla, P. dolichorhiza, P. erioderma, P. extenuata, P. fimbriata sp. nov., P. granulosa sp. nov., P. koponenii sp. nov., P. montis-wilhelmii sp. nov., P. nana, P. oceanica, P. papuana sp. nov., P. sumatrana, P. ulcerata, and P. weberi sp. nov. Peltigera macra and P. tereziana var. philippinensis are reduced to synonymy with P. nana, whereas P. melanocoma is maintained as a species distinct from P. nana pending further studies. The status of several putative taxa referred to P. dolichorhiza s. lat. in the Sect. Polydactylon remains to be studied on a wider geographical scale and in the context of P. dolichorhiza and P. neopolydactyla. The phylogenetic affinities of all but one regional species (P. extenuata) are studied based on inferences from ITS (nrDNA) sequence data, in the context of a broad taxonomic sampling within the genus. -

Lišejníky Chráněných Území Na Babě a Vraní Skála Na Křivoklátsku

Bryonora 53 (2014) 1 LIŠEJNÍKY CHRÁNĚNÝCH ÚZEMÍ NA BABĚ A VRANÍ SKÁLA NA KŘIVOKLÁTSKU Lichens of protected areas Na Babě and Vraní skála in the Křivoklát region (Central Bohemia) Jiří M a l í č e k 1 & Jana K o c o u r k o v á 2 1Přírodovědecká fakulta Univerzity Karlovy, Katedra botaniky, Benátská 2, CZ-128 01 Praha 2, e-mail: [email protected]; 2Fakulta životního prostředí České zemědělské univerzity v Praze, Kamýcká 129, CZ-165 21 Praha 6 – Suchdol, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Two small-sized protected areas involving open rocky sites and surrounding woodlands were surveyed in the Křivoklát region. One-hundred seventy-five lichens, lichenicolous fungi and lichen allied fungi are reported from the protected area Na Babě. The reserve is characterized by xerothermic vegetation (oak forests, grasslands, rocks) and a rather diverse bedrock. The area is rich in saxicolous and poor in epiphytic lichen species. The most valuable communities are on ±shady slate and greywacke rocks (with e.g. Bacidia arceutina, Diplotomma canescens, Endocarpon psorodeum, Hyperphyscia adglutinata, Phaeophyscia chloantha). From this locality, we publish two new species for the Czech Republic, a lichenicolous lichen Miriquidica instrata and a lichenicolous fungus Abrothallus tulasnei. Eighty-one taxa are reported from the protected area Vraní skála (chert rock). Aspicilia gibbosa, Cladonia glauca, Dimelaena oreina, and Pleopsidium chlorophanum represent the most interesting records. According to comparison with historical literature, the saxicolous flora on Vraní skála persists nearly without any change. Key words: Abrothallus tulasnei, Miriquiridica instrata, chert rock, lichen diversity Úvod Křivoklátsko patří v rámci středních Čech k přírodovědně nejcennějším oblastem. -

Some Notes on Acarosporaceae in South America

Opuscula Philolichenum, 11: 31-35. 2012. *pdf available online 3January2012 via (http://sweetgum.nybg.org/philolichenum/) Some Notes on Acarosporaceae in South America 1 KERRY KNUDSEN ABSTRACT. – Three species and one genus are reported new for South America (all are from Ecuador): Acarospora americana, Caeruleum heppii, and Polysporina simplex. Acarospora catamarcae and A. thelomma are verified as distinct species occurring in Argentina. Acarospora punae is placed in synonymy with A. thelomma and lectotypes are designated for both names. Acarospora sparsiuscula is also verified as a distinct species, originally described from Argentina and here reported from the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador. A total of twenty-seven species of Acarosporaceae are recognized as occurring in South America in this ongoing taxonomic series. KEYWORDS. – Biodiversity, taxonomy. INTRODUCTION This paper is a new installment of a continuing series of studies Acarosporaceae in South America (Knudsen 2007a; Knudsen & Flakus 2009; Knudsen et al. 2008, 2010, 2011, in press.). In this paper I examine two species described by Magnusson (1947) from South America, Acarospora catamarcae H. Magn. and A. sparsiuscula H. Magn., and two species described by Lamb (1947) from South America, A. thelomma I.M. Lamb and A. punae I.M. Lamb. During the period of this study I also examined specimens collected by Zdenek Palice in Ecuador (PRA) and by Andre Aptroot on the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador (CDS) as well as specimens from Graz (GZU). A current checklist with literature references is also included. Species are only included in the checklist if they have been verified by myself as part of this continuing study. -

Piedmont Lichen Inventory

PIEDMONT LICHEN INVENTORY: BUILDING A LICHEN BIODIVERSITY BASELINE FOR THE PIEDMONT ECOREGION OF NORTH CAROLINA, USA By Gary B. Perlmutter B.S. Zoology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 1991 A Thesis Submitted to the Staff of The North Carolina Botanical Garden University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Advisor: Dr. Johnny Randall As Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Certificate in Native Plant Studies 15 May 2009 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 2 This Final Project, whose results are reported herein with sections also published in the scientific literature, is dedicated to Daniel G. Perlmutter, who urged that I return to academia. And to Theresa, Nichole and Dakota, for putting up with my passion in lichenology, which brought them from southern California to the Traingle of North Carolina. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter I: The North Carolina Lichen Checklist…………………………………………………7 Chapter II: Herbarium Surveys and Initiation of a New Lichen Collection in the University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU)………………………………………………………..9 Chapter III: Preparatory Field Surveys I: Battle Park and Rock Cliff Farm……………………13 Chapter IV: Preparatory Field Surveys II: State Park Forays…………………………………..17 Chapter V: Lichen Biota of Mason Farm Biological Reserve………………………………….19 Chapter VI: Additional Piedmont Lichen Surveys: Uwharrie Mountains…………………...…22 Chapter VII: A Revised Lichen Inventory of North Carolina Piedmont …..…………………...23 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..72 Appendices………………………………………………………………………………….…..73 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 4 INTRODUCTION Lichens are composite organisms, consisting of a fungus (the mycobiont) and a photosynthesising alga and/or cyanobacterium (the photobiont), which together make a life form that is distinct from either partner in isolation (Brodo et al. -

Contrasting Patterns in Lichen Diversity in the Continental and Maritime Antarctic

Accepted Manuscript Contrasting patterns in lichen diversity in the continental and maritime Antarctic Shiv Mohan Singh, Maria Olech, Nicoletta Cannone, Peter Convey PII: S1873-9652(15)30004-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.polar.2015.07.001 Reference: POLAR 246 To appear in: Polar Science Received Date: 3 January 2015 Revised Date: 13 April 2015 Accepted Date: 22 July 2015 Please cite this article as: Singh, S.M., Olech, M., Cannone, N., Convey, P., Contrasting patterns in lichen diversity in the continental and maritime Antarctic, Polar Science (2015), doi: 10.1016/ j.polar.2015.07.001. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 1 Contrasting patterns in lichen diversity in the continental and maritime Antarctic 2 3 Shiv Mohan Singh a* , Maria Olech b, Nicoletta Cannone c, Peter Convey d 4 5 aNational Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research, Ministry of Earth Sciences, 6 Vasco-Da-Gama, Goa 403804, India 7 8 bInstitute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kopernica 27, 31-501Cracow, Poland 9 10 cDepartment of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, Insubria University, via Valleggio, 11 11 – 22100 – Como (CO) -Italy 12 13 dBritish Antarctic Survey, Madingley Road, High Cross Cambridge CB3 0ET United 14 Kingdom 15 16 17 *For correspondence: [email protected] 18 19 20 Abstract 21 Systematic surveys of the lichen floras of MANUSCRIPTSchirmacher Oasis (Queen Maud Land, 22 continental Antarctic), Victoria Land (Ross Sector, continental Antarctic) and 23 Admiralty Bay (South Shetland Islands, maritime Antarctic) were compared to help 24 infer the major factors influencing patterns of diversity and biogeography in the three 25 areas.