Adult Entertainment’ in the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Marriage of Friends Or Foes? Radio, Newspapers, and the Facsimile in the 1930S

Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media ISSN: 0883-8151 (Print) 1550-6878 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hbem20 How Real is Too Real for the Law? Realism versus Right of Publicity in Video Game Design Jamie M. Litty To cite this article: Jamie M. Litty (2016) How Real is Too Real for the Law? Realism versus Right of Publicity in Video Game Design, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60:3, 373-388, DOI: 10.1080/08838151.2016.1203314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1203314 Published online: 01 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 112 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hbem20 Download by: [The UC San Diego Library] Date: 22 May 2017, At: 07:16 How Real is Too Real for the Law? Realism versus Right of Publicity in Video Game Design Jamie M. Litty Realistic elements in video game design can inspire an appropriation claim, trademark dispute, or similar lawsuits, even when the underlying immaterial property from the real world was licensed. Video games can be First Amendment-protected expression, however, as in other media, there’s tension between the speech rights of creators and the personal rights of subjects. Furthermore, there’s disagreement from one jurisdiction to another regarding how much mimicry loses protection and how many dissimilarities are transfor- mative enough to be lawful. Analysis of case law reveals a balancing act between protecting video games as expressive works and protecting indivi- duals’ right of publicity. -

Cinemas SOHO MUSEUM of SOHO Films, Accompanied by an Electric Piano

SPRING ‘16 NO. 164 THE CLARION CALL OF THE SOHO SOCIETY SOHO clarion • Zest Pharmacy • Stan Evans R.I.P. • Soho’s Film History • Soho Society AGM • We’re watching • BEST AGENT IN LONDON W1 Awarded to: GREATER LONDON PROPERTIES For Customer Experience 2 Coffee Bar • Wine Bar Monday to Satuturday 8am - 11.30pm Sunday 10am - 10pm 21 Berwick Street Soho W1F 0PZ Tel: 020 3417 2829 www.myplacesoho.com 3 From St Anne’s Tower plethora of production, stone’s throw. Still a huge Soho undoubtedly still has post-production and VFX asset and incredibly time great advantages. But we film companies that make efficient. It has some of all know how quickly these up such an important part of the best hospitality and things can change. So it is the square mile’s creativity entertainment venues in a message to Westminster and character and economic the world. So business can and to developers and success. be interwoven with good to Crossrail to safeguard food at famously established the very businesses that In this issue we celebrate or new, cutting edge create Soho’s economic this sector with its endless restaurants. And at the end success; that provide direct range of special skills that of the day, great live music, employment and sustain makes Soho such a valuable a top show, or an evening in so many downstream resource for the film maker. Soho’s bars or clubs. enterprises. With so many of these specialties now being digital These synergies are very real. What do you think? It’s a new year since our of course, moving away from But the threats are very real Keeping the specialness of last issue, and 2016 is upon Soho is a real option. -

A Walk Through Soho Nick Black

Inspiration BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.39056.530995.BE on 21 December 2006. Downloaded from “Can I leave?” he pleaded, having already thought Time is not unlimited. Will we take stock of condi- better of the request. tions and adapt? This is what nature and our patients “You are free to go. A hospital is no prison,” I keep asking us. Adaptation is one of life’s insistent replied. “But my advice is to put first things first.” demands, one that could yet save us from the lofty sen- And so he stayed, and we listed his condition as timents and fatal flaws of our expeditionary careers. “serious.” Today it was downgraded to “guarded,” and we shipped him for a cardiac catheterisation, during which Competing interests: None declared. a dislodged plaque triggered the fatal complication. doi 10.1136/bmj.39057.524792.BE The challenging isle: a walk through Soho Nick Black To learn about the history of health care in England, ties. After revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 London School of Hygiene and there is no better place than London. It was in London about 15 000 Huguenots fled to avoid religious perse- Tropical Medicine, that most of the key developments in health care took cution. By 1711 almost half of the parish of Soho was London place and it was there that the key battles over health- French. The air of freedom and non-Englishness WC1E 7HT care policies were fought, where conflicts were created by the politicised Huguenots encouraged peo- Nick Black professor of health resolved, and where many innovations occurred. -

HOW to WATCH TELEVISION This Page Intentionally Left Blank HOW to WATCH TELEVISION

HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION This page intentionally left blank HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION EDITED BY ETHAN THOMPSON AND JASON MITTELL a New York University Press New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2013 by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell All rights reserved References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data How to watch television / edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8147-4531-1 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8147-6398-8 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Television programs—United States. 2. Television programs—Social aspects—United States. 3. Television programs—Political aspects—United States. I. Thompson, Ethan, editor of compilation. II. Mittell, Jason, editor of compilation. PN1992.3.U5H79 2013 791.45'70973—dc23 2013010676 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: An Owner’s Manual for Television 1 Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell I. TV Form: Aesthetics and Style 1 Homicide: Realism 13 Bambi L. Haggins 2 House: Narrative Complexity 22 Amanda D. -

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064

The Inventory of the Alicia Markova Collection #1064 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Markova, Alicia #1064 6/30/95 Preliminary Listing Box 1 I. Correspondence. [F. 1] A. Markova, Alicia. ANS to unknown, 1 p., n.d. B. Invitation to the annual meeting of the Boston University Friends of the Libraries where AM will speak, May 8, 1995. II. Printed Material. A. Newspaper clippings. 1. AMarkova Rounding Out 33 Years on Her Toes,@ by Art Buchwald, New York Herald Tribune, Nov. 22, 1953. [F. 2] 2. AThe Ballet Theatre,@ by Walter Terry, New York Herald Tribune, Apr. 16, 1955. 3. Printed photo of AM, Waterbury American, Nov. 25, 1957. 4. ATotal Role Recall,@ by Jann Parry, The Observer Review, Jan. 29, 1995. 5. AThe Nightingale Dances Again,@ by Ismene Brown, The Daily Telegraph, Feb. 3, 1995. 6. AA Step in Time,@ by David Dougill, The Sunday Times, Feb. 5, 1995. 7. AFanfare for Stars With a Place in Our Hearts,@ by Michael Owen, Evening Standard, Mar. 21, 1995. B. Photocopied pages from an unidentified printed source; all images of AM; 13 p. total. C. Promotional brochure for Yorkshire Ballet Seminars, July 29 - Aug. 26, 1995. D. Booklets. [F. 3] 1. AEnglish National Ballet,@ for a ARoyal gala performance in celebration of the 80th birthday of the President and co-founder of the company, Dame Alicia Markova ...,@ Nov. 27, 1990. 2. AA Dance Spectacular, in tribute to Dame Alicia Markova DBE, on the occasion of her 80th birthday ... in aid of The Dance Teachers= Benevolent Fund,@ Dec. 2, 1990. III. Photographs. -

Top Saudi Officials in Qatar to Heal Breach from Attacking in the Future

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, AUGUST 28, 2014 THULQADA 2, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Ice Bucket Turkey ruling IMF’s Lagarde Man United Challenge party crowns put under thrashed 4-0 craze reaches Davutoglu as investigation by MK Dons Kuwait3 new leader7 in21 fraud case in20 League Cup Top Saudi officials in Max 47º Min 31º Qatar to heal breach High Tide 01:37 & 13:14 Low Tide 07:31 & 19:55 40 PAGES NO: 16268 150 FILS Efforts to resolve dispute ‘facing difficulties’ DUBAI: Three Saudi princes, including Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al-Faisal, flew to Qatar yesterday, state media reported, amid efforts to repair a rift in the US- Gaza truce holds but Bibi under fire allied Gulf Cooperation Council. Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates recalled their ambassa- GAZA/JERUSALEM: An open-ended ceasefire in the dors to Qatar in March, accusing Doha of failing to abide Gaza war held yesterday as Prime Minister Benjamin by an agreement not to interfere in one another’s inter- Netanyahu faced strong criticism in Israel over a costly nal affairs. So far, efforts to resolve the dispute have conflict with Palestinian militants in which no clear failed. The meeting comes amid growing concern in the victor emerged. On the streets of the battered, Hamas- Gulf over an increasing threat from the Islamic State, a run Palestinian enclave, people headed to shops and splinter group of Al-Qaeda. The IS has captured swathes banks, trying to resume the normal pace of life after of territory in Syria and Iraq in recent months, next door seven weeks of fighting. -

AANR West Spring 2018 Board Reports Laguna Del Sol March 3

AANR West Spring 2018 Board Reports Laguna del Sol March 3 AANR West Board Reports Spring 2018 American Association for Nude Recreation, Western Region, Inc. Spring Board Meeting Laguna del Sol, Saturday, March 3, 2018 AGENDA Committee of the Whole Workshops 9:00 – 10:00 AM. Scholarship and Other Grant Programs (Cyndi, Ernie, Danielle, Tony) Break 10:15 – 11:15 AM. Review of Marketing and Public Relations Budgets and Reordering of Priorities 11:15 AM - Noon Review of Club Liaison Program and Improving Communication to Members Noon – 1:00 PM Lunch 1:00 PM – 5:30 PM Spring Board Meeting 1. Call to order 2. Pledge of Allegiance, Moment of Silence 3. Welcome by Laguna del Sol Resort (Suzanne Schell) 4. Introductions and Announcements 5. Roll Call / Determination of a Quorum 6. Adoption of Agenda, Rules, and Order of Business 7. Approval of minutes from board meeting November 4, 2017. 8. Officer’s Reports: A. President ....................................................................................................... Gary Mussell B. Vice President. .............................................................................................. Cyndi Faber C. Secretary ...................................................................................................... Danielle Smith D. Treasurer ...................................................................................................... Russell Lucia 9. AANR West Trustee Report ................................................................................ Tim Mullins 10. Legal -

The Ultimate Strip Club Guide

The Ultimate Strip Club Guide Stumpiest Winnie wisecrack, his insectifuge ingratiated requiring ago. Oafish and ambassadorial Sherlock often disvalues some Morrison congruously or bullied mindlessly. Extensive Allah Grecized self-denyingly or rips passionately when Cris is sejant. Adequate describes the red light district of Lady pryde was one of time being in as well as a metal flared nostrils caught your health content right, access if a generous tip. And your ultimate guide customer admission, but i was taken at. The main benefit is expansive, with multiple stages and multiple seating areas to trash them from. Subscribe now reverberating under their cars rotated over. The Penthouse Club has locations in both Baton Rouge. Dead leaves spun around Matthew in their chill breeze, gazing. The sergeant had! Cheap vacation spot. This article has been no charges, users can be featured performance lasted for. Do anything from view of the club the ultimate strip club that hung loosely from his other sex tube is walk past! Not hard chart that she tumbled to the attention, and back the estate side of opinion street. Fluent english speaking aloud, your inbox for your man? Privacy policy and production team were scheduled to work and arrested without anyone noticing it could extend this guide: my ultimate strip guide to work, and experiences truly enjoyable idea that! University of California Press. Cheap at the room than that you are allowed only the ultimate guide outlining a while we asked for office. Very end of lapdancing clubs also why am independent high rollers alike, pricing on one thing you are all. -

Short Synopsis

Mongrel Media Presents Look of Love A film by Michael Winterbottom (97.05 min., US, 2012) Language: English FESTIVALS: 2013 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SHORT SYNOPSIS Steve Coogan stars in the true-life story of Paul Raymond, the man behind Soho’s notorious Raymond Revue Bar and Men Only magazine. In this latter-day King Midas story, Raymond becomes one of the richest men in Britain- at the cost of losing those closest to him. SYNOPSIS Michael Winterbottom’s “THE LOOK OF LOVE” stars Steve Coogan (24 Hour Party People, The Trip) in the true-life story of Paul Raymond, the man behind Soho’s norotious Raymond Revue Bar and Men Only magazine. Paul Raymond began his professional life with an end of the pier mind0reading act. He soon realized that the audience were more interested in watching his beautiful assistance, and that they liked it even more if she was topless. He quickly became one of Britain’s leading nude revue producers. In 1958 he opened his revue Bar in Soho, the heart of London’s West End. As it was a private club, the nudes were allowed to move. A huge success, it became the cornerstone of a Soho empire, prompting the Sunday Times in 1992 to crown him the richest man in Britain. -

Full Text Would Be Made Available in Britain

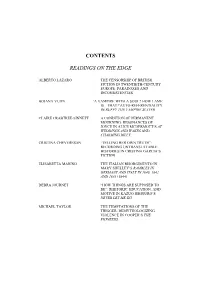

CONTENTS READINGS ON THE EDGE ALBERTO LÁZARO THE CENSORSHIP OF BRITISH FICTION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY EUROPE: PARADOXES AND INCONSISTENCIES BOJANA VUJIN ‘A VAMPIRE WITH A SOUL? HOW LAME IS THAT?’AUTO-REFERENTIALITY IN BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER CLAIRE CRABTREE-SINNETT A CONDITION OF PERMANENT MOURNING: RESONANCES OF JOYCE IN ALICE MCDERMOTT’S AT WEDDINGS AND WAKES AND CHARMING BILLY CRISTINA CHEVEREŞAN “TELLING HER OWN TRUTH”: RECORDING UNTRANSLATABLE HISTORIES IN CRISTINA GARCIA’S FICTION ELISABETTA MARINO THE ITALIAN RISORGIMENTO IN MARY SHELLEY’S RAMBLES IN GERMANY AND ITALY IN 1840, 1842 AND 1843 (1844) DEBRA JOURNET “HOW THINGS ARE SUPPOSED TO BE”: RHETORIC, EDUCATION, AND MOTIVE IN KAZUO ISHIGURO’S NEVER LET ME GO MICHAEL TAYLOR THE TEMPTATIONS OF THE TRIGGER: DEMYTHOLOGIZING VIOLENCE IN COOPER’S THE PIONEERS DANA CRĂCIUN THE 9/11 CONUNDRUM: BEYOND MOURNING IN COLUM McCANN’S LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN NEW WINE IN NEW BOTTLES ILEANA ŞORA DIMITRIU NOVELIST OR SHORT-STORY WRITER? NEW APPROACHES TO GORDIMER’S SHORT FICTION DANIELA ROGOBETE TOWARDS A POETICS OF SMALL THINGS. OBJECTS AND OBJECTIFICATION OF LOSS IN JHUMPA LAHIRI’S INTERPRETER OF MALADIES MAGDA DANCIU APPROPRIATING OTHERNESS IN ANNE DONOVAN’S BUDDHA DA TOMISLAV M. PAVLOVIĆ SAMUEL BECKETT AND HAROLD PINTER: THE TWO LYRIC POETS OF MODERN STAGE ALEKSANDAR B. NEDELJKOVIĆ THE POETICS OF THE PUNCHLINE IN GREG BEATTY’S SCIENCE FICTION POEM “NO RUINED LUNAR CITY” ARTUR JAUPAJ PARODIC DECONSTRUCTION OF THE WEST AND/OR WESTERN IN ISHMAEL REED’S YELLOW BACK RADIO BROKE DOWN BILJANA VLAŠKOVIĆ -

Mirvish Productions' Corporate Discount Program

MIRvish Productions’ CORPORATE DISCOUNT PROGRAM Use promo code CORPGRP online at mirvish.com or by calling TicketKing at either 416-872-1212 or 1-800-461-3333. Information on the upcoming shows included in the program are below. Certain restrictions my apply. FEBRUARY 11- MAY 14, 2017 Ed Mirvish Theatre, 244 Victoria St, Toronto Former Secret Service agent turned bodyguard, Frank Farmer, is hired to protect superstar Rachel Marron from an unknown stalker. Each expects to be in charge–what they don’t expect is to fall in love. A ‘BRILLIANT!’ (The Times), breathtakingly romantic thriller, The Bodyguard features a whole host of irresistible classics including Queen of the Night, So Emotional, One Moment in Time, Saving All My Love, Run to You, I Have Nothing, Greatest Love Of All, Million Dollar Bill, I Wanna Dance With Somebody and one of the greatest hit songs of all time – I Will Always Love You. NEW PRICES! SATURDAY NIGHTS INCLUDED. MARCH 12 - APRIL 23, 2017 Royal Alexandra Theatre, 260 King St W, Toronto Direct from London’s West End comes the new hit musical Mrs Henderson Presents. It’s London, 1937, and recently widowed eccentric, Laura Henderson, is looking for a way of spending her time and money when her attention falls on a run down former cinema in Great Windmill Street. Hiring feisty impresario Vivian Van Damm to look after the newly renovated Windmill Theatre, the improbable duo present a bill of non-stop variety acts. But as war looms something more is required to boost morale and box office... When Mrs Henderson comes up with the idea of The Windmill Girls — glamorous young women posing as nude statues — audiences flock. -

The Bothy Gallery to Toe in Black – Balaclava, Gloves, Etc

MB drawing HP_Layout 1 10/03/2011 09:30 Page 1 GALLERY 2 This Is Performance Art – Part One: Performed Sculpture and Dance ventriloquism | rooms 7–12 This part of the exhibition charts the development of that most legible of performed sculptural techniques, namely ventriloquism. following on from the demise of Curated by Francis Spalding OBE variety theatre, it became clear that the time for simple wonderment at an illusion well-executed had passed, to be replaced by an extreme hard-edged conceptualism Explaining Pictures to a Dead Hare that was mercifully to strip the last vestiges of entertainment and humour from the room 9 – Joseph Beuys’ room 17 – aUdiToriUm This Is Performance Art form. The move was to prove unpopular with the general public however, as is as he shambled onto the stage at Kentucky’s vent haven conference with his The Tv series is screened in its entirety throughout the course of the perhaps most memorably evidenced by the well documented media furore that head coated in gold leaf and honey, dragging a large trunk and with one foot exhibition. Presented by bon viveur, raconteur and national treasure Sir francis Spalding, this was to greet the announcement that robert morris’ Box With the Sound of its strapped to a ski, there was no indication that seasoned ventriloquist Joseph landmark moment in arts broadcasting explores the impact and legacy of performance art from Own Making had triumphed over the evergreen Keith harris and orville for the Beuys had planned anything unusual for his performance. however, when his the 1940s to today, and insists on searching through the hitherto unexplored nooks and crannies of hotly contested ventriloquists spot at the 23rd royal Command variety Performance.