Museum Ireland 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Monthly Council Meeting, 08/01

To the Lord Mayor and Report No. 01/2018 Members of Dublin City Council FÓGRA FREASTAIL DO CHRUINNIÚ MÍOSÚIL NA COMHAIRLE I SEOMRA NA COMHAIRLE, HALLA NA CATHRACH, CNOC CHORCAÍ, DÉ LUAIN, AR 8 EANÁIR 2018 AG 6.15 I.N. NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY COUNCIL MEETING TO BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, CITY HALL, DAME STREET, DUBLIN 2., ON MONDAY 8 JANUARY 2018 AT 6.15 PM Do Gach Ball den Chomhairle. A Chara, Iarrtar ort a bheith I láthair ag an Cruinniú Míosúil de Chomhairle Cathrach Bhaile Átha Cliath a thionólfar i Seomra na Comhairle, Halla na Cathrach, Cnoc Chorcaí, ar 8 Eanáir 2018 ag 6.15 i.n. chun an ghnó seo leanas a phlé agus gach is gá i dtaca leis a dhéanamh, nó a chur a dhéanamh, nó a ordú a dhéanamh:- Silent Prayer/Reflection PAGE PART I - INTRODUCTORY 1 Lord Mayor's Business 2 Ceisteanna fé Bhuan Ordú Úimhir 16 5 - 16 3 LETTERS (a) Letter dated 14th December 2017 from Clare County Council - Calling on the 17 - 18 Minister for Agriculture to put a plan in place to help Clare farmers through an imminent fodder crisis next year (b) Letter dated 12th December 2017 from Galway City Council - Calling on the 19 - 20 Department of the Environment re request for the preparation of legislation for the disposal of paint under the Producer Responsibility Initiative PART II - GOVERNANCE ISSUES 4 To confirm the minutes of the Monthly Council Meeting 4th December and the 21 - 88 13th December 2017 5 Report No. 6/2018 of the Head of Finance (K. -

(Shakey) Bridge History

A History of Daly’s Bridge & Surrounds, Cork DR KIERAN MCCARTHY WWW.CORKHERITAGE.IE Entering Cork History Cork has experienced every phase of Irish urban development Each phase informing the next phase Challenge of engineering a city upon a swamp –reclamation issues Challenge of the city’s suburban topography and the hills and geology Some eras are busier in development than other eras ➢ Some sites are more pivotal than others for the city’s development ➢ Some sites have become more famous than others in the city’s development ➢ Mardyke area and site of Daly’s Bridge were and are very important (three centuries in the making) Both the latter looked at first in the early eighteenth century …pre 1700… to 1750 Corke c.1601 (Hardiman Collection TCD) Early 1700s Expansion Spread Source: Charles Smith, 1750 (Source: Cork City Library) Joseph O’Connor, 1774 (source: Cork City Library) Joseph O’Connor, 1774 (source: Cork City Library) Beauford 1801 (Source: Cork City Library) John Carr, Cork from the Mardyke Walk, 1806 (source: Crawford Art Gallery) Beauford, 1801 (source: Cork City Library) The Ferry Site: Ferry rights across the River Lee to the market were passed down from the Weber family to the Carlton family and then came to the Dooley family. In August 1824, it is recorded in the Cork Constitution newspaper that John Dooley of the Ferry Walk Sunday’s Well claimed compensation in consequence of the new Wellington Bridge to be built near the western end of the Mardyke. Mr Dooley claimed that his ferry rights would be injured. He had held the ferry for many years, but on cross-examination he admitted that he had no exclusive rights. -

Cork City Libraries Summer Reading Challenge 2019 | Join Red and His Friends for a Summer of Reading Fun | Register Now

corkcitylibraries.ie Events Edition July/August 2019 18 Photo Claire Keogh You hold in your hands a very special publication – the first Events of the New City. On 31 May many months of planning and preparation came to fruition when Ballincollig, Glanmire, and Blarney Libraries joined the City Libraries network. They join the other seven libraries – the City Library on Grand Parade, - Hollyhill, Blackpool and Mayfield libraries on the Northside, as well as Douglas, Tory Top and Bishopstown Libraries south of the river, making a much stronger library network. Cork City Council Libraries do not see the revision of the City Council boundary as the City Council Library Service expanding and, in the process, absorbing three new libraries and the surrounding catchment areas. Rather, we see it as an opportunity to create a new Library Service for a New City. We bring with us all that we as a service have learned in 127 years, our many strengths and achievements. We must be – and will be – open to other ideas and ways of doing things. We will be open to the experiences of the staff and patrons of our new libraries, in Ballincollig, Glanmire, and Blarney. Highlights this summer include Heritage Week, which runs from 17 to 25 August, ‘Branch Out and Read’, our summer reading challenge for kids as well as ‘The Summer School of Creative Writing’ which takes place in the City Library, Ballincollig and Glanmire Libraries. The new city will also see a host of exhibitions on display in all our libraries. Looking forward to seeing you, your family and friends in your local library during the first summer of our New City. -

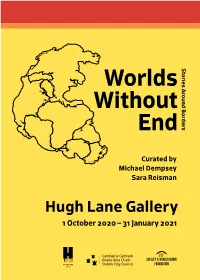

Curated by Michael Dempsey Sara Reisman Introduction

Curated by Michael Dempsey Sara Reisman Introduction SELECT AN ARTIST t Lieven De Boeck Elaine Byrne John Byrne Tony Cokes Chto Delat Dor Guez Lawrence Abu Hamdan Dragana Juriši´c Ari Marcopoulos Raqs Media Collective Dermot Seymour Mark Wallinger “In the year 2000 there was a total of fifteen fortified border walls and fences between sovereign nations. Today, physical barriers at sixty-three borders divide nations across four continents.” — Lawrence Abu Hamdan, 2018 Introduction Historically, borders tend to be the location of international trouble spots. Prior to the global lockdown, there was a utopian vision of open borders, alongside the reality of a populist push towards border fortification. This dichotomy has now been eclipsed by a pandemic that doesn’t respect borders. Politicisation of the pandemic, displacement of people, and contagion, as well as the drive towards an ever-increasing economic globalisation, have created further complex contradictions. The curatorial idea for the exhibition Worlds Without End (WWE) was first conceived a year ago as a research-based collaboration between Sara Reisman, Executive and Artistic Director of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, New York and Michael Dempsey, Head of Exhibitions, Hugh Lane Gallery, who are the co-curators of WWE. WWE is a visual dialogue on the impact of borders on individuals and communities. The twelve participating artists are drawn from different regional traditions and challenge our perceptions of national identities, envisioning utopian possibilities for understanding the place of borders, their proliferation and seeming obsolescence, in contemporary society. These artists reveal their deep interest in current geo-political positions and social conditions with works that interrogate power structures, positions of privilege and human rights issues. -

Homage to Fra Angelico (1928) Oil on Canvas, 183 X 152.5Cms (72 X 60’’)

38 31 Mainie Jellett (1897-1944) Homage to Fra Angelico (1928) Oil on canvas, 183 x 152.5cms (72 x 60’’) Provenance: From the Collection of Dr. Eileen MacCarvill, Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin Exhibited: Mainie Jellett Exhibition, Dublin Painters Gallery 1928 Irish Exhibition of Living Art, 1944, Cat. No. 91 An Tostal-Irish Painting 1903-1953, The Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, Dublin 1953 Mainie Jellett Retrospective 1962, Hugh Lane Gallery Cat. No. 38 Irish Art 1900-1950, Cork ROSC 1975, The Crawford Gallery, Cork, 1975, Cat. No. 65 The Irish Renaissance, Pyms Gallery, London, 1986, Cat. No. 39 Mainie Jellett Retrospective 1991/92, Irish Museum of Modern Art Cat. No. 89 The National Gallery of Ireland, New Millennium Wing, Opening Exhibition of 20th Century Irish Paintings, January 2002-December 2003 The Collectors’ Eye, The Model Arts & Niland Gallery, Sligo, January-February 2004, Cat. No. 12; The Hunt Museum, Limerick, March-April 2004 A Celebration of Irish Art & Modernism, The Ava Gallery, Clandeboye, June- September 2011, Cat. No 21 Analysing Cubism Exhibition Irish Museum of Modern Art Feb/May 2013, The Crawford Gallery Cork June / August 2014 and The FE Mc William Museum September/November 2013 Irish Women Artists 1870 - 1970 Summer loan exhibition Adams Dublin July 2014 and The Ava Gallery , Clandeboye Estate August/September Cat. No. 70. Literature: The Irish Statesman, 16th June 1928 Stella Frost, A Tribute to Evie Hone & Mainie Jellett, Dublin 1957, pp19-20 Kenneth McConkey, A Free Spirit-Irish Art 1860-1960, 1990, fig 58 p75 Dr. S.B. Kennedy, Irish Art & Modernism, 1991, p37 Bruce Arnold, Mainie Jellett and the Modern Movement in Ireland, 1991, full page illustration p120 Mainie Jellett, IMMA Cat, No. -

Hugh Lane Gallery Update Report

Report to Arts, Culture, Leisure and Recreation SPC 29th June 2020 Item No. 8 HUGH LANE GALLERY Online Programmes and Social Media Engagement In response to the Covid 19 Pandemic and the restrictions that have been put in place, the Hugh Lane Gallery has created a series of new and highly dynamic online programmes which are updated weekly. The response has been excellent with our line audience growing exponentially. Our Twitter engagements reached 282k by the end of May. We aim to reach 10,000 followers on Instagram by mid-July and our Facebook followers are growing steadily. Our first online Sunday@Noon concert took place on the 31st March with over 3,000 people + listening through Facebook. All of the gallery’s programmes can be accessed through our website and on Hugh Lane Gallery YouTube channel and Hugh Lane Gallery Soundcloud. Our programmes are a mixture of talks, mini podcasts, sketching and drawing classes, Artists Takeover, Curators Choice, # museumfromhome and # Flashback Fridays (see www.hughlane.ie). The Gallery Newsletter goes out weekly via email and I hope every Councillor is receiving it. We currently have a subscription of over 3,600.and we have approximately 1200 active readers. According the Constant Contact’s statistics page, the 30% open rate is 18% higher than the Industry Average which is normally 12%. INSTAGRAM FOLLOWER GROWTH 10000 9000 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL MAY Currently at 9264, we project to hit 10,000 followers by mid-July FACEBOOK REACH 50000 45000 40000 35000 30000 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL Facebook Reach Facebook Reach is the number of unique people viewing our content through following, sharing or liking our content. -

Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross B

Kerlin Gallery Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross b. 1956, Cork, Ireland Like many of Dorothy Cross’ sculptures, Family (2005) and Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) sees the artist work with found objects, transforming them with characteristic wit and sophistication. Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) presents a pair of deflated footballs, no longer of use, their past buoyancy now anchored in bronze. Emerging from each is a cast of the artist’s hands, index finger extended upwards in a pointed gesture suggesting optimism or aspiration. In Family (2005) we see the artist’s undeniable craft and humour come together. Three spider crabs were found, dead for some time but still together. The intricacies of their form and the oddness of their sideways maneuvres forever cast in bronze. The ‘father’ adorned with an improbable appendage also pointing upwards and away. --- Working in sculpture, film and photography, Dorothy Cross examines the relationship between living beings and the natural world. Living in Connemara, a rural area on Ireland’s west coast, the artist sees the body and nature as sites of constant change, creation and destruction, new and old. This flux emerges as strange and unexpected encounters. Many of Cross’ works incorporate items found on the shore, including animals that die of natural causes. During the 1990s, the artist produced a series of works using cow udders, which drew on the animals' rich store of symbolic associations across cultures to investigate the construction of sexuality Dorothy Cross Right Ball and Left Ball 2007 cast bronze, unique 34 x 20 x 19 cm / 13.4 x 7.9 x 7.5 in 37 x 19 x 17 cm / 14.6 x 7.5 x 6.7 in DC20407A Dorothy Cross Family 2005 cast bronze edition of 2/4 dimensions variable element 1: 38 x 19 x 20 cm / 15 x 7.5 x 7.9 in element 2: 25 x 24 x 13 cm / 9.8 x 9.4 x 5.1 in element 3: 16 x 15 x 13 cm / 6.3 x 5.9 x 5.1 in DC17405-2/4 Dorothy Cross b. -

O'brien Cahirmoyle LIST 64

Leabharlann Naisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 64 PAPERS OF THE FAMILY OF O’BRIEN OF CAHIRMOYLE, CO. LIMERICK (MSS 34,271-34,277; 34,295-34,299; 36,694-36,906) (Accession No. 5614) Papers of the descendents of William Smith O’Brien, including papers of the painter Dermod O’Brien and his wife Mabel Compiled by Peter Kenny, 2002-2003 Contents Introduction 7 The family 7 The papers 7 Bibliography 8 I. Land tenure 9 I.1. Altamira, Co. Cork 9 I.2 Ballybeggane 9 I.3. Bawnmore 9 I.4. Cahirmoyle 9 I.5. Clanwilliam (Barony) 11 I.6. Clorane 11 I.7. The Commons, Connello Upper 11 I.8. Connello (Barony) 11 I.9. Coolaleen 11 I.10. Cork City, Co. Cork 11 I.11. Dromloghan 12 I.12. Garrynderk 12 I.13. Glanduff 12 I.14. Graigue 12 I.15. Killagholehane 13 I.16. Kilcoonra 12 I.17. Killonahan 13 I.18. Killoughteen 13 I.19. Kilmurry (Archer) 14 I.20. Kilscannell 15 I.21. Knockroedermot 16 I.22. Ligadoon 16 I.23. Liscarroll, Co. Cork 18 I.24. Liskillen 18 I.25. Loghill 18 I.26. Mount Plummer 19 I.27. Moyge Upper, Co. Cork 19 I.28. Rathgonan 20 2 I.29. Rathnaseer 21 I.30. Rathreagh 22 I.31. Reens 22 I.32 Correspondence etc. relating to property, finance and legal matters 23 II. Family Correspondence 25 II.1. Edward William O’Brien to his sister, Charlotte Grace O’Brien 25 II.2. Edward William O’Brien to his sister, Lucy Josephine Gwynn (d. -

Cork City Attractions (Pdf)

12 Shandon Tower & Bells, 8 Crawford Art Gallery 9 Elizabeth Fort 10 The English Market 11 Nano Nagle Place St Anne’s Church 13 The Butter Museum 14 St Fin Barre’s Cathedral 15 St Peter’s Cork 16 Triskel Christchurch TOP ATTRACTIONS IN CORK C TY Crawford Art Gallery is a National Cultural Institution, housed in one of the most Cork City’s 17th century star-shaped fort, built in the aftermath of the Battle Trading as a market since 1788, it pre-dates most other markets of it’s kind. Nano Nagle Place is an historic oasis in the centre of bustling Cork city. The The red and white stone tower of St Anne’s Church Shandon, with its golden Located in the historic Shandon area, Cork’s unique museum explores the St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is situated in the centre of Cork City. Designed by St Peter’s Cork situated in the heart of the Medieval town is the city’s oldest Explore and enjoy Cork’s Premier Arts and Culture Venue with its unique historic buildings in Cork City. Originally built in 1724, the building was transformed of Kinsale (1601) Elizabeth Fort served to reinforce English dominance and Indeed Barcelona’s famous Boqueria market did not start until 80 years after lovingly restored 18th century walled convent and contemplative gardens are salmon perched on top, is one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. One of the history and development of: William Burges and consecrated in 1870, the Cathedral lies on a site where church with parts of the building dating back to 12th century. -

Culture-Night-Cork-City-2016

CULTURE NIGHT FRI SEP 16 REVOLVES AROUND YOU CORK CITY 2016 Over 100 venues and 200 events all FREE until late. There are new experiences waiting, so join us to explore Cork’s Culture after dark... #culturenightcork2016 #LOVECulture For more information: For updates see: Please note that all information Information Desk is correct at time of going to Cork City Hall www.culturenightcork.ie press. Additional Venues may be Anglesea Street, Cork added to the programme after going to print. t: 021 492 4042 twitter.com/corkcityarts e: [email protected] facebook.com/corkcityarts Check the website for updates. Culture Night Cork City is brought to you by the Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs in partnership with Cork City Council. 1 CONTENTS General Info .................................................................... 1 Secret Gig ........................................................................ 3 Perceptions 2016 ............................................................. 4 On the Trail of the Poets .................................................. 6 1916 Trail ......................................................................... 7 The Lee Sessions .............................................................. 8 A-Z of venues/events ..................................................... 10 Culture Night Buses ....................................................... 51 Index ............................................................................. 52 SHHHHHH… Map .............................................................................. -

Download Our 2021 Catalogue

Contents Customer Service Information 2 Medieval Studies 3–11 Trinity Medieval Ireland Series 6–7 Dublin City Council Series 12 Early Modern Studies 12, 14 Local History 15 Modern Studies 13–23 Irish Legal History Society Series 8, 14, 20 20th-Century Studies 24–31 Media Studies 28 Science 29 The Making of Dublin City Series 31 Music 32 Folklore 33 National University of Ireland Publications 33 Select Backlist 34–5 Order Form 36 2 7 Malpas Street Dublin 8, D08 YD81 Four Courts Press Four Courts Ireland Tel.: International + 353-1-4534668 Web: www.fourcourtspress.ie Four Courts Press Email: [email protected] Well our 50th anniversary year (2020) didn’t go exactly to plan . and for a myriad of covid reasons our schedule of publications fell somewhat behind. So as we head out into a new year, with a little more hope now perhaps, some of our ‘friends’ from last year are to be found among an exciting new list of books for 2021. We embark on our journey this year in the company of Adomnán and Columba, and meet along the way William Marshal, Prior John de Pembridge and the swashbuckling Captain Cuéllar. After a sojourn along the streets of medieval Dublin we visit the Elizabethan Quadrangle at Trinity College, before surveying the final stand of the rebels on Vinegar Hill. We chart the rise and fall of the Orange Order during the Great Famine, examine the lavish contents of country houses, and chronicle the remarkable career of Teresa Ball, founder of the Loreto schools. Along the way we review the changing fortunes of Henrietta Street in Dublin, the politics and political culture of the long eighteenth century in Ireland, a new history of the city and county of Limerick, and we hear harp music from around the world. -

HOW to ORGANISE a Lifelong Learning Festival

HOW TO ORGANISE A Lifelong learning festival op tips and advice T English Version Tina Neylon Lifelong Learning Festival Co-ordinator, United Nations International Conference Cork, Ireland Educational, Scientific and on Learning Cities Cultural Organization Cork - 2017 Spanish Version Organización International Conference de las Naciones Unidas on Learning Cities para la Educación, Cork - 2017 la Ciencia y la Cultura French Version Organisation International Conference des Nations Unies on Learning Cities pour l’éducation, Cork - 2017 la science et la culture Over the years I have been contacted by people from around Ireland TOP and the world, asking for information about how the Cork Lifelong Learning Festival started and advice on how to make such an event a success. TIPS Some have since started their own – the first was Limerick seven years ago, which has Start small and build up been a great success. Others Individuals and organisations may have unrealistic expectations – they offer to run a series of events but find include Wyndham, a suburb attendances are low. It is much better to organise one event of Melbourne, and Burnaby in the first time they get involved and gradually build on its British Columbia, Canada. success, learning on the way how to attract the public. This guide tries to answer any questions anyone may have All participation voluntary and, by charting how the There should be no compulsion to get involved - even if an Cork festival has developed, organisation is in receipt of State funding. All participation offer some advice to anyone in the Cork festival is on a voluntary basis and that contributes to the positive and welcoming atmosphere considering following in our at events.