Biblis38 Text.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soulsabbath.Pdf

SOUL SABBATH SYNOPSIS Even as a child, Mieszko’s parents knew there was something not quite right about the boy, and when they saw him drawing a picture of a woman with wolf-like characteristics, they were convinced he was “unsound” and handed him over to the local Benedictine monastery, abandoning him forever. Mieszko would spend the rest of his life in that monastery until one day he simply vanished without a trace. Though he took his vows very seriously, he could no longer maintain his silence when an epiphany came to him that certain scriptures were not gospel at all – an offense that exposed him as a heretic. Mieszko’s revelation concerned the redemption of mankind, and such heresy shook the monastery to its very foundation. Though this was a crime punishable by death, Mieszko was able to bargain for his life, but it could be argued that the punishment delivered was, in fact, worse than death. The bricks were gathered, the mortar poured, and Mieszko was confined in the tiny scriptorium and assigned the task of scribing the greatest book of his time – The Codex Gigas. Even as Mieszko dropped to his knees to enter the tomb, he could not repent of the truth he had been shown, and he began the monumental chore, not to find forgiveness, but to pay homage to his convictions. Although he was writing possessed, Mieszko knew in his heart that he could never complete this impossible task alone – not in his current form. Still, he labored, and with each stroke of the quill, he became more a part of the book, until he was absorbed into the very book itself. -

Studies in the History of the Greek Text of the Apocalypse: the Ancient

STUDIE S IN THE HISTORY OF THE GREEK TEXT OF THE APOCALYPSE: THE ANCIENT STEMS Press SBL T EXT-CRITICAL STUDIES M ichael W. Holmes, General Editor Number 11 Press SBL STUDIE S IN THE HISTORY OF THE GREEK TEXT OF THE APOCALYPSE: THE ANCIENT STEMS Josef Schmid Translated and Edited by Juan Hernández Jr., Garrick V. Allen, and Darius Müller Press SBL Atlanta C opyright © 2018 by Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, LSB Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schmid, Josef, 1893–1975, author. |Hernández, Juan, Jr., 1968–, translator. Title: Studies in the history of the Greek text of the Apocalypse : the ancient stems / by Josef Schmid ; translated and edited by Juan Hernández Jr., Garrick V. Allen, and Darius Müller. Other titles: Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Apokalypse-Textes. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, 2018. | Series: Text-critical studies ; Number 11 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2018005081 (print) | LCCN 2018024401 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142812 (ebk.) | ISBN 9781628372045 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780884142829 (hbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Revelation. Greek—Criticism, Textual—History. Classification: LCC BS2825.52 (ebook) | LCC BS2825.52 .S35813 2018 (print) | DDC 228/.0486—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018005081 Press Printed on acid-free paper. -

What Scriptures Or Bible Nearest to Original Hebrew Scriptures? Anong Biblia Ang Pinaka-Malapit Sa Kasulatang Hebreo

WHAT BIBLE TO READ WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? ANONG BIBLIA ANG PINAKA-MALAPIT SA KASULATANG HEBREO KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL ni Isagani Datu-Aca Tabilog WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL Original King Iames Bible 1611 See the Sacred Name YAHWEH in modern Hebrew name on top of the Front Cover 1 HEXAPLA FIND THE DIFFERENCE OF DOUAI BIBLE VS. KING JAMES BIBLE Genesis 6:1-4 Genesis 17:9-14 Isaiah 53:8 Luke 4:17-19 AND MANY MORE VERSES The King James Version (KJV), commonly known as the Authorized Version (AV) or King James Bible (KJB), is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England begun in 1604 and completed in 1611. First printed by the King's Printer Robert Barker, this was the third translation into English to be approved by the English Church authorities. The first was the Great Bible commissioned in the reign of King Henry VIII, and the second was the Bishops' Bible of 1568. -

The Import of the Versions for the History of the Greek Text: Some Observations from the ECM of Acts1

The Import of the Versions for the History of the Greek Text: Some Observations from the ECM of Acts1 Georg Gäbel Akademie-Projekt “Novum Testamentum Graecum–Editio Critica Maior” Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung Evangelisch-theologische Fakultät, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster Abstract: In this article, I discuss the relevance of the versions for Greek textual history, taking as my starting point the forthcoming Editio Critica Maior of Acts. After a brief introduction to the citation of versional material in the ECM of Acts, three groups of examples are presented: (1) examples where each versional variant is correlated with one Greek variant, (2) examples of variants found in versional witnesses belonging to the D-trajectory and believed to have existed in now lost Greek witnesses, and (3) ex- amples for the mutual influence of Greek and versional texts. I conclude that (1) careful attention to the versions will benefit our understanding of Greek textual history, that (2) some variants of Greek origin not attested in the Greek manuscripts now known can be reconstructed on the basis of the versions, and that (3) in some cases, particularly in bilingual manuscripts, there is likely to have been versional influence on the Greek text. I. Introduction and Basics 1. Introduction Ut enim cuique primis fidei temporibus in manus venit codex graecus et aliquantulum facultatis sibi utriusque linguae habere videbatur, ausus est interpretari. (For as soon as, in the early times of the faith, a Greek codex came into the hands of anyone who also believed to possess even a little grasp of both languages, he dared to translate.) Augustine, Doctr. -

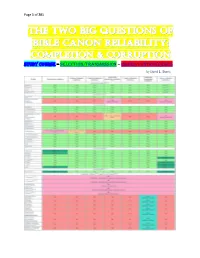

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

(Rev 12 : 15) – from Etymology to Theologoumenon

„Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny” 66 (2013) nr 2 REV. WIESŁAW ALICKI Ποταμοφόρητος (Rev 12 : 15) – from Etymology to Theologoumenon 1. Discrepancies in the translation of ποταμοφόρητος In the translation of Rev 12 : 15 in the New American Bible we can read the following words: “The serpent, however, spewed a torrent of water out of his mouth after the woman to sweep her away with the current.” The original Greek version is as follows: καὶ ἔβαλεν ὁ ὄφις ἐκ τοῦ στόματος αὐτοῦ ὀπίσω τῆς γυναικὸς ὕδωρ ὡς ποταμόν, ἵνα αὐτὴν ποταμοφόρητον ποιήσῃ.1 G. Schneider suggests the correction of the meaning of the word ποταμοφόρητος towards a considerable simplification: “in order to drown h e r.” 2 Since the comments concerning this fragment of the text are not de- tailed, the effort we are making in this paper to analyse it seems reasonable. 1 There are no significant differences shown by the critical apparatus, except for slight changes, e.g. ταυτην instead of αυτην or ποιησει instead of ποιηση; cf. Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio octava critica maior, rec. C. Tischendorf, vol. 2, Lipsiae 1872, ad loc. Regardless of the passage of time, Tischendorf’s edition is still the most detailed one. 2 “um sie vom Strom forttreiben zu lassen, d.h. sie zu ertränken;” G. Schneider, ποταμοφόρητος, [in:] Exegetisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, vol. 1–3, hrsg. H. Balz, G. Schneider, Stuttgart-Berlin-Köln 1992², vol. 3, p. 338. K. H. Rengstorf’s pro- posal is marked in italics, with no details of interpretation included; cf. K. H. Rengstorf, 128 Rev. -

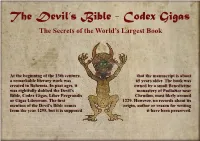

Codex Gigas the Secrets of the World’S Largest Book

The Devil’s Bible - Codex Gigas The Secrets of the World’s Largest Book At the beginning of the 13th century, that the manuscript is about a remarkable literary work was 65 years older. The book was created in Bohemia. In past ages, it owned by a small Benedictine was rightfully dubbed the Devil’s monastery of Podlažice near Bible, Codex Gigas, Liber Pergrandis Chrudim, most likely around or Gigas Librorum. The first 1229. However, no records about its mention of the Devil’s Bible comes origin, author or reason for writing from the year 1295, but it is supposed it have been preserved. The Largest Manuscript Book of the World The book is unusually large; it is thus no wonder that it was compared to the Seven Wonders of the World in the Middle Ages. It is about 900 mm tall, 505 mm wide and weighs an awesome 75 kilograms. It contains 312 parchment folios, hence 624 pages. It is reckoned that the skin of about 160 animals was necessary to acquire the writing material. What is fascinating is the unity of the book, concord of the writing and initial letters, harmony of the overall composition and individual details; all the texts are still legible even today. All the indications are that it was a life work of one person. Historians estimate that the scribe in question must have conceivably spent as many as twenty years on such a monumental work. A Work of the Devil The existence of the book is connected with a legend about the Devil, according to which it was also given its popular name – the Devil’s Bible, and the very depiction of the devil is its integral part. -

An Analysis of Readings in D

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Repetitive prophetical and interpretative formulations in Luke's Gospel of Codex Bezae : an analysis of readings in D Welch Jr, Bobby Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 BANGOR UNIVERSITY REPETITIVE PROPHETICAL AND INTERPRETATIVE FORMULATIONS IN LUKE'S GOSPEL OF CODEX BEZAE: AN ANALYSIS OF READINGS IN D A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION BY BOB WELCH BANGOR, WALES, UK SEPTEMBER 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Author All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation is an analysis of a pattern of redactional doublets within the early 5th CE Greek-Latin bilingual New Testament manuscript of Codex Bezae (D), specifically in the Gospel of Luke. Seven doublets are examined in comparison with Codex Vaticanus (B). -

Codex Gigas Ita Pdf

Codex gigas ita pdf Continue Codex Gigas: The Devil's Bible: The Gigas Codex, otherwise known as the Devil's Bible, is probably the largest and strangest manuscript in the world. It measures about 1 meter in length and is so large that it requires at least the efforts of two people to lift it. The history of the Gigas Code According to legend, the medieval manuscript is the result of a pact with the devil, so it is sometimes called the Bible of the Devil. The origin of Codex Gigas is unknown. A note written on the margins of the manuscript indicates that in 1295 its owners, the monks of Podladice, were engaged in the Sedlets monastery. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Bshevnov Monastery, near Prague. All these monasteries were in the Czech Republic, the present Czech Republic, and he is sure that the Codex Gigas was built somewhere in this region, but not necessarily in Podlacec, a small and unimportant monastery. In 1594, Rudolf II brought codex Gigas to his Prague castle, where he remained there until the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War, stolen along with many other treasures of the Swedish army. After the robbery, it entered the collection of the Swedish queen Cristina and placed in the royal library of Stockholm Castle. He remained there until 1877, when he joined the National Library of Sweden, also in Stockholm. Legend As reported by the website of the National Library of Sweden, there is a legend about the creation of the Gigas Code, according to which it will be the work of a monk, an onerous task attributed to him to atone for his sins. -

Bible 1 the Bible (From Koine Greek Τὰ Βιβλία, Tà Biblía, "The Books") Is A

Bible 1 Bible The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, "the books") is a canonical collection of texts considered sacred in Judaism or Christianity. Different religious groups include different books within their canons, in different orders, and sometimes divide or combine books, or incorporate additional material into canonical books. Christian Bibles range from the sixty-six books of the Protestant canon to the eighty-one books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church canon. The Gutenberg Bible, the first printed Bible The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, contains twenty-four books divided into three parts; the five books of the Torah ("teaching" or "law"), the Nevi'im ("prophets"), and the Ketuvim ("writings"). The first part of Christian Bibles is the Old Testament, which contains, at minimum, the twenty-four books of the Hebrew Bible divided into thirty-nine books and ordered differently than the Hebrew Bible. The Catholic Church and Eastern Christian churches also hold certain deuterocanonical books and passages to be part of the Old Testament canon. The second part is the New Testament, containing twenty-seven books; the four Canonical gospels, Acts of the Apostles, twenty-one Epistles or letters and the Book of Revelation. By the 2nd century BCE Jewish groups had called the Bible books "holy," and Christians now commonly call the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Bible "The Holy Bible" (τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια, tà biblía tà ágia) or "Holy Scriptures" (Αγία Γραφή, Agía Graphḗ). Many Christians consider the whole canonical text of the Bible to be divinely inspired. The oldest surviving complete Christian Bibles are Greek manuscripts from the 4th century.