The Import of the Versions for the History of the Greek Text: Some Observations from the ECM of Acts1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soulsabbath.Pdf

SOUL SABBATH SYNOPSIS Even as a child, Mieszko’s parents knew there was something not quite right about the boy, and when they saw him drawing a picture of a woman with wolf-like characteristics, they were convinced he was “unsound” and handed him over to the local Benedictine monastery, abandoning him forever. Mieszko would spend the rest of his life in that monastery until one day he simply vanished without a trace. Though he took his vows very seriously, he could no longer maintain his silence when an epiphany came to him that certain scriptures were not gospel at all – an offense that exposed him as a heretic. Mieszko’s revelation concerned the redemption of mankind, and such heresy shook the monastery to its very foundation. Though this was a crime punishable by death, Mieszko was able to bargain for his life, but it could be argued that the punishment delivered was, in fact, worse than death. The bricks were gathered, the mortar poured, and Mieszko was confined in the tiny scriptorium and assigned the task of scribing the greatest book of his time – The Codex Gigas. Even as Mieszko dropped to his knees to enter the tomb, he could not repent of the truth he had been shown, and he began the monumental chore, not to find forgiveness, but to pay homage to his convictions. Although he was writing possessed, Mieszko knew in his heart that he could never complete this impossible task alone – not in his current form. Still, he labored, and with each stroke of the quill, he became more a part of the book, until he was absorbed into the very book itself. -

Codex Bezae (D05) in Light of P.Oxy. 4968 (127): a Reassessment of “Anti-Judaic Tendencies” in Acts 10–17

「성경원문연구」 41 (2017. 10.), 280-303 ISSN 1226-5926 (print), ISSN 2586-2480 (online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2017.10.41.280 http://ibtr.bskorea.or.kr Codex Bezae (D05) in Light of P.Oxy. 4968 (127): A Reassessment of “Anti-Judaic Tendencies” in Acts 10–17 Hannah S. An* 1. Introduction Eldon Jay Epp’s classic monograph, The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in the Acts, marked a watershed moment in contemporary text-critical scholarship. Epp attempted to chart a coherent picture of the theological tendencies in Codex Bezae (D05) through a systematic treatment of the D-variants.1) He argues that underpinning the distinctive variants of the D-text (or the “Western” text)2) are the scribal tendencies of a Gentile Christian perspective that portray the Jews, and their leaders, as responsible for the death of Jesus, and hostile toward His apostles. Epp’s study has generated both positive and negative reactions in the field of New Testament textual criticism.3) * Ph.D. in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary, USA. Assistant Professor of Old Testament at Torch Trinity Graduate University, Seoul. [email protected]. 1) E. J. Epp, The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in Acts, SNTS 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966); “The ‘Ignorance Motif’ in Acts and Anti-Judaic Tendencies in Codex Bezae”, HTR 55 (1962), 51-62. Also see Epp’s recent reassessment of his own thesis in E. J. Epp, “Anti-Judaic Tendencies in the D-text of Acts: Forty Years of Conversation”, E. J. Epp, ed., Perspectives on New Testament Textual Criticism: Collected Essays, 1962-2004, SNT 116 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 699-739. -

The Order of the Gospels in the Parent of Codex Bezae. 339

J. Chapman, The order of the Gospels in the parent of Codex Bezae. 339 The order of the Gospels in the parent of Codex Bezae. By Dom J. Chapman, O. S. B. Erdington Abbey, Birmingham. Certain phenomena in Codex Bezae show that the Gospels are not given in the order of its archetype. They may be exhibited in the form of five arguments. It is to be remembered that the Gospels appear in the MS in the usual old Latin order: Mt Jo Lc MC. i. The punctuation of the MS consists "chiefly of a blank space between the words, or of a middle, sonietimes of an upper, very seldom of a lower single point, usually placed in the middle of a verse or crixoc, and found (äs in most other copies) much more thickly in some parts than in others: such a point is often set in the middle of a line, in passages whefe it is hard to see its use." So far Scrivener, p. xviii. Dr. Rendel Harris, on the other hand, has shown that the points, and perhaps the spaces, are traces of the original colometry of the arche- type, thus marked by the scribe, when he did not preserve the lines of his copy. Dr. Harris has pointed out their similarity to the points in the Curetonian Syriac and in the old Latin MS k (Study of Cod. Bezae, eh. xxiii; but contrast Burkitt, Evang. Da-Mepk. ii, p. 14). An examination of the points shows that they are very numerous in Matthew and in the early part of John. -

Studies in the History of the Greek Text of the Apocalypse: the Ancient

STUDIE S IN THE HISTORY OF THE GREEK TEXT OF THE APOCALYPSE: THE ANCIENT STEMS Press SBL T EXT-CRITICAL STUDIES M ichael W. Holmes, General Editor Number 11 Press SBL STUDIE S IN THE HISTORY OF THE GREEK TEXT OF THE APOCALYPSE: THE ANCIENT STEMS Josef Schmid Translated and Edited by Juan Hernández Jr., Garrick V. Allen, and Darius Müller Press SBL Atlanta C opyright © 2018 by Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, LSB Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schmid, Josef, 1893–1975, author. |Hernández, Juan, Jr., 1968–, translator. Title: Studies in the history of the Greek text of the Apocalypse : the ancient stems / by Josef Schmid ; translated and edited by Juan Hernández Jr., Garrick V. Allen, and Darius Müller. Other titles: Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Apokalypse-Textes. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, 2018. | Series: Text-critical studies ; Number 11 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2018005081 (print) | LCCN 2018024401 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142812 (ebk.) | ISBN 9781628372045 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780884142829 (hbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Revelation. Greek—Criticism, Textual—History. Classification: LCC BS2825.52 (ebook) | LCC BS2825.52 .S35813 2018 (print) | DDC 228/.0486—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018005081 Press Printed on acid-free paper. -

A Historyof Research on Codex Bezae

Tyndale Bulletin 47.1 (May, 1996) 185-187. A HISTORY OF RESEARCH ON CODEX BEZÆ1 Kenneth E. Panten Introduction Considering the amount of material written on Codex Bezæ down through the centuries, a detailed history of research into the codex has long been overdue. Such a history is important not only to give future researchers an understanding of what has gone on before, but also to facilitate an understanding of the development of ideas and their outcome. As Codex Bezæ is the principal witness of the so-called Western text, much of what has been written focuses on its text. From the end of the last century, however, there has been a growing awareness among scholars of the need to give the other details contained within the codex far more attention than hitherto. Inasmuch as the D text is the main rival to the Alexandrian text as the best representative of the original exemplar, it is of no surprise that Codex Bezæ and its text have been of interest to the textual critics. Over the last century and a half there have always been those advocating the supremacy of the D text, and such claims have attracted much attention. For this reason, Codex Bezæ has never been far from the focus of scholarly debate. This debate would be greatly helped if Codex Bezæ could be accurately located historically, for this is the nub of the problem—where and when was it written? Any avenue of inquiry ever pursued, any investigation ever embarked upon, has the answer to this question as its prime objective. -

TEXT-TYPES? Characteristics / Readings, Unique to Their Location, Resulting in Localized Text-Types Or Textual Families

As individual New Testament books were received and circulated in the early Christian church, various copies were made and deployed NEW TESTAMENT throughout the ancient world. As manuscripts were circulated within particular geographical regions they began to take on particular TEXT-TYPES? characteristics / readings, unique to their location, resulting in localized text-types or textual families. The Alexandrian text-type is the form of The Western text-type is the form of the New Testament text witness in ALEXANDRIAN Greek New Testament that predominates WESTERN the Old Latin and Peshitta translations from the Greek, and also in in the earliest surviving documents, as well quotations from the 2nd and 3rd century Christian writers, including as the text-type used in Egyptian Coptic Cyprian, Tertullian, and Irenaeus. Alexandrian Codex Sinaiticus manuscripts. manuscripts are is considered to characteristic by be Western in its majuscule or the first eight uncial texts. Above chapters of is John 1:1 in Codex John’s Gospel Only one Greek uncial manuscript is considered to transmit a Western text The two oldest Sinaiticus in its for the four Gospels and the Book of Acts, the fifth century Codex Bezae; the and closest to EARLIER upper case sixth century Codex Clarmontanus is considered to transmit a western text complete copies majuscule texts for Paul’s letters and is followed by two ninth century uncials: F and G. of the New א Codex Sinaiticus - 01 330-360 AD Other early manuscripts of note Testament, are P66 and P75. Codex Sinaiticus Many, if not most, textual critics today believe that and Codex there were two major early text-types that can be Vaticanus,* are ascertained, the Alexandrian and Western. -

What Scriptures Or Bible Nearest to Original Hebrew Scriptures? Anong Biblia Ang Pinaka-Malapit Sa Kasulatang Hebreo

WHAT BIBLE TO READ WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? ANONG BIBLIA ANG PINAKA-MALAPIT SA KASULATANG HEBREO KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL ni Isagani Datu-Aca Tabilog WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL Original King Iames Bible 1611 See the Sacred Name YAHWEH in modern Hebrew name on top of the Front Cover 1 HEXAPLA FIND THE DIFFERENCE OF DOUAI BIBLE VS. KING JAMES BIBLE Genesis 6:1-4 Genesis 17:9-14 Isaiah 53:8 Luke 4:17-19 AND MANY MORE VERSES The King James Version (KJV), commonly known as the Authorized Version (AV) or King James Bible (KJB), is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England begun in 1604 and completed in 1611. First printed by the King's Printer Robert Barker, this was the third translation into English to be approved by the English Church authorities. The first was the Great Bible commissioned in the reign of King Henry VIII, and the second was the Bishops' Bible of 1568. -

Acts - Revelation the Aramaic Peshitta & Peshitto and Greek New Testament

MESSIANIC ALEPH TAV INTERLINEAR SCRIPTURES (MATIS) INTERLINEAR VOLUME FIVE ACTS - REVELATION THE ARAMAIC PESHITTA & PESHITTO AND GREEK NEW TESTAMENT With New Testament Aramaic Lexical Dictionary (Compiled by William H. Sanford Copyright © 2017) Printed by BRPrinters The Messianic Aleph Tav Interlinear Scriptures (MATIS) FIRST EDITION Acts - Revelation Volume Five ARAMAIC - GREEK Copyright 2017 All rights reserved William H. Sanford [email protected] COPYRIGHT NOTICE The Messianic Aleph Tav Interlinear Scriptures (MATIS), Acts - Revelation, Volume Five, is the Eastern Aramaic Peshitta translated to English in Interlinear and is compared to the Greek translated to English in Interlinear originating from the 1987 King James Bible (KJV) which are both Public Domain. This work is a "Study Bible" and unique because it is the first true interlinear New Testament to combine both the John W. Etheridge Eastern Aramaic Peshitta in both Aramaic and Hebrew font compared to the Greek, word by word, in true interlinear form and therefore comes under copyright protection. This is the first time that the John W. Etheridge Eastern Aramaic Peshitta has ever been put in interlinear form, word by word. The John W. Etheridge Eastern Aramaic Peshitta English translation was provided by Lars Lindgren and incorporates his personal notes and also, the Hebrew pronunciation of the Aramaic is unique and was created and provided by Lars Lindgren and used with his permission…all of which is under copyright protection. This publication may be quoted in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio), up to and inclusive of seventy (70) consecutive lines or verses, without express written permission of William H. -

Luke 3:22-38 in Codex Bezae: the Messianic King George E

Andrews University Semimy Studies, Autumn 1979, Vol. XVII, No. 2, 203-208 Copyright @ 1979 by Andrews University Press. BRIEF NOTE LUKE 3:22-38 IN CODEX BEZAE: THE MESSIANIC KING GEORGE E. RICE Andrews University The work of the textual critic has long centered in the task of col- lating manuscripts, counting variants, and computing the results for the purpose of placing manuscripts in their proper text -types. This process is essential for building a critical text. However, as important as this , work may be, dealing statistically with variant readings can result in a neglect of the contribution the variants make to the meaning of the text. The contribution of a variant reading can be fully appreciated only when the degree of difference it brings to the text is evaluated. As K. W. Clark says: Counting words is a meaningless measure of textual variation, and all such estimates fail to convey the theological significance of variable readings. Rather it is required to evaluate the thought rather than to compute the ver- biage. How shall we measure the theological clarification derived from textual emendation where a single word altered affects the major concept in a passage? . By calculating words it is impossible to appreciate the spiritual insights that depend upon the words.' It is only when one realizes that many variant readings resulted from theological biases that textual criticism becomes exciting. The textual critic then finds himself discontented with collating three or four scattered chapters of a book for purposes of placing a manuscript in its proper text-type. Three or four chapters of one of the gospels, e.g., are not sufficient to isolate a pattern of theological biases that may lie behind variant readings. -

Biblis38 Text.Indd

fig. 1. christina svensson, bookbinder, national library of sweden 6 Excerpt from the periodical Biblis no 38 michael gullick The Codex Gigas A revised version of the George Svensson lecture delivered at The National Library of Sweden, Stockholm, November 2006 he medieval manuscript known as the Codex Gigas in the Na- tional Library of Sweden (its call number is A 148) is famous for two features. First, it is very large with a page size that was originally about 900 × 460 mm, although it is now a little T smaller due to retrimming when rebound in the early nineteenth cen- tury (fig. 1). Secondly, it contains a full-page portrait of the Devil that has led to the name ‘Devil’s Bible’ as an alternative to Codex Gigas. (Gigas means literally gigantic or enormous.) These two features have long been known, and the manuscript is one of the largest, if not the largest, European medieval manuscript to have survived into modern times. There are three fundamental questions that need to be asked of any medieval manuscript: When was it made, where was it made and who made it? These questions have been asked again recently as the entire manuscript is to be put onto the world wide web, and the following observations are based upon a re-examination and re-evaluation of the manuscript by myself and others that will be incorporated into the web site as an introduction and commentary. Despite the name ‘Devil’s Bible’, the manuscript contains a number of texts in addition to a complete Bible. -

THE EARLIEST NEW TESTAMENT. WE Have Been Assisted in the Restoration of Codex Bezae (EXPOSITOR, July, Pp

119 THE EARLIEST NEW TESTAMENT. WE have been assisted in the restoration of Codex Bezae (EXPOSITOR, July, pp. 46-53) by the consideration that those of the Fathers who used a "Western" text of the New Testament did not know all the Catholic Epistles, at least so far as we can tell. The only Greek manuscript which contains a text wholly Western in foundation (however much spoiled by correctors), is necessarily typical. Its ascertained contents may now be compared with the New Testament books known to the Fathers who used a " Western " text. A few of these Fathers have bequeathed to us such abundant writings that we can tell with some certainty what books they knew or did not know. The following list tabulates this comparison. I have added the " Cheltenham catalogue," called in Ger many the'' Mommsen'sche Verzeichniss." As one of the codices which contains it is at St. Gall, while the other is no longer at Cheltenham, I prefer to call it "Mommsen's list." I do not include the Muratorian canon, as it is de fective ~ eclectic. I I 1 2 3 4 5 I 6 7 Cod. Canon Iren- Tertul- Clem. Cyprian (Papias) Bezae Mom ms. aeus Al. lian --- Mt. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Mc. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Le. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Jo. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes i Yes Acts Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes I ? xiii Paul [Cod. Yes Yes Yes Yes I Yes ? Clar.) I Hehr. I [Yes) [Yes] James 1 Pet. -

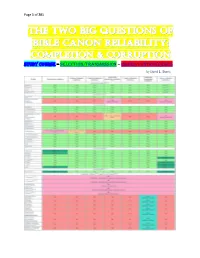

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration.