Armstrong Racial Origins Aug 18 2016 Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Lassiter Cv March 2020 Copy

Curriculum Vitae Matthew D. Lassiter Department of History (734) 546-0799 1029 Tisch Hall [email protected] University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Education __________________________________________________ Ph.D., Department of History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville VA, May 1999. Dissertation: “The Rise of the Suburban South: The ‘Silent Majority’ and the Politics of Education, 1945-1975.” M.A., Department of History, University of Virginia, Jan. 1994. Thesis: “Biblical Fundamentalism and Racial Beliefs at Bob Jones University.” B.A., History, summa cum laude, Furman University, Greenville SC, May 1992. Employment/Teaching ________________________________________ Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2017- Arthur F. Thurnau Professor (since 2015) Associate Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2006-2017 Assistant Professor of History, University of Michigan, 2000-2006 Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Michigan, 2017- Associate Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, 2006-2017 Director of Policing and Social Justice Lab, University of Michigan, 2018- Director of Undergraduate Studies, History Department, 2012-2014 Director of Graduate Studies, History Department, 2006-2008 History 202: “Doing History” (undergraduate methods seminar). History 261: “U.S. History Since 1865” (lecture). History 329: “Crime and Drugs in Modern America” (lecture/‘flipped’ class format). History 364: “History of American Suburbia” (lecture). History 467: “U.S. History Since 1945” (lecture). History/American Culture 374: “Politics and Culture of the Sixties” (lecture). History 196: “Political Culture of Cold War America” (undergraduate seminar). History 399: “Environmental Activism in Michigan” (undergraduate seminar). History 399: “Cold Cases: Police Violence, Crime, and Social Justice in Michigan” (undergraduate HistoryLab seminar) History 497: “War on Crime/War on Drugs” (undergraduate seminar). -

Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History

Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History Heather Ann Thompson As the twentieth century came to a close and the twenty-first began, something occurred in the United States that was without international parallel or historical precedent. Be- tween 1970 and 2010 more people were incarcerated in the United States than were imprisoned in any other country, and at no other point in its past had the nation’s eco- nomic, social, and political institutions become so bound up with the practice of punish- ment. By 2006 more than 7.3 million Americans had become entangled in the criminal justice system. The American prison population had by that year increased more rapidly than had the resident population as a whole, and one in every thirty-one U.S. residents was under some form of correctional supervision, such as in prison or jail, or on proba- tion or parole. As importantly, the incarcerated and supervised population of the United States was, overwhelmingly, a population of color. African American men experienced the highest imprisonment rate of all racial groups, male or female. It was 6.5 times the rate of white males and 2.5 times that of Hispanic males. By the middle of 2006 one in fifteen black men over the age of eighteen were behind bars as were one in nine black men aged twenty to thirty-four. The imprisonment rate of African American women looked little better. It was almost double that of Hispanic women and three times the rate of white women.1 Despite the fact that ten times more Americans were imprisoned in the last decade of the twentieth century than were killed during the Vietnam War (591,298 versus 58,228), and even though a greater number of African Americans had ended up in penal institu- tions than in institutions of higher learning by the new millennium (188,500 more), his- torians have largely ignored the mass incarceration of the late twentieth century and have not yet begun to sort out its impact on the social, economic, and political evolution of the postwar period. -

Mandy Diss Post-Defense Word

Silencing the Cell Block: The Making of Modern Prison Policy in North Carolina and the Nation by Amanda Bell Hughett Department of History Duke University Date: July 7, 2017 Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Laura F. Edwards ___________________________ Edward Balleisen ___________________________ Christopher W. Schmidt ___________________________ Heather Ann Thompson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 ABSTRACT Silencing the Cell Block: The Making of Modern Prison Policy in North Carolina and the Nation by Amanda Bell Hughett Department of History Duke University Date: July 7, 2017 Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Laura F. Edwards ___________________________ Edward Balleisen ___________________________ Christopher W. Schmidt ___________________________ Heather Ann Thompson An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Amanda Bell Hughett 2017 Abstract “Silencing the Cell Block” examines the relationship between imprisoned activists and civil liberties lawyers from the 1960s to the present in order to solve a puzzle central to the United States’ peculiar criminal justice system: Why do American prisons, despite affording -

AHA Colloquium

Cover.indd 1 13/10/20 12:51 AM Thank you to our generous sponsors: Platinum Gold Bronze Cover2.indd 1 19/10/20 9:42 PM 2021 Annual Meeting Program Program Editorial Staff Debbie Ann Doyle, Editor and Meetings Manager With assistance from Victor Medina Del Toro, Liz Townsend, and Laura Ansley Program Book 2021_FM.indd 1 26/10/20 8:59 PM 400 A Street SE Washington, DC 20003-3889 202-544-2422 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.historians.org Perspectives: historians.org/perspectives Facebook: facebook.com/AHAhistorians Twitter: @AHAHistorians 2020 Elected Officers President: Mary Lindemann, University of Miami Past President: John R. McNeill, Georgetown University President-elect: Jacqueline Jones, University of Texas at Austin Vice President, Professional Division: Rita Chin, University of Michigan (2023) Vice President, Research Division: Sophia Rosenfeld, University of Pennsylvania (2021) Vice President, Teaching Division: Laura McEnaney, Whittier College (2022) 2020 Elected Councilors Research Division: Melissa Bokovoy, University of New Mexico (2021) Christopher R. Boyer, Northern Arizona University (2022) Sara Georgini, Massachusetts Historical Society (2023) Teaching Division: Craig Perrier, Fairfax County Public Schools Mary Lindemann (2021) Professor of History Alexandra Hui, Mississippi State University (2022) University of Miami Shannon Bontrager, Georgia Highlands College (2023) President of the American Historical Association Professional Division: Mary Elliott, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (2021) Nerina Rustomji, St. John’s University (2022) Reginald K. Ellis, Florida A&M University (2023) At Large: Sarah Mellors, Missouri State University (2021) 2020 Appointed Officers Executive Director: James Grossman AHR Editor: Alex Lichtenstein, Indiana University, Bloomington Treasurer: William F. -

0727 Cyrus Obrien Dissertation FINAL

Redeeming Imprisonment: Religion and the Development of Mass Incarceration in Florida by Cyrus J. O’Brien A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Matthew Lassiter, Chair Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Stuart Kirsch Professor Heather Ann Thompson Cyrus J. O’Brien [email protected] [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0620-0938 © Cyrus J. O’Brien 2018 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements are the first thing I read when I pick up a book or browse through a dissertation, and they always put me in a good mood. I love the ways they speak to networks of camaraderie, convey thanks to amazing mentors, pay homage to intellectual genealogies, acknowledge long-lasting relationships to people and places, situate the author institutionally, and celebrate friendships and other joys of life. Like many dissertation writers, I have many relationships to celebrate and much to be grateful for. What follows is a woefully inadequate message of thanks. First and foremost, I thank the people who helped with this research whom I am unable to name. Scores of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people helped me figure out what was happening in Florida prisons, and I am indebted to each of them. I also want to thank the many volunteers and prison staff who generously talked with me, answered my questions, and helped me understand their work and lives. I particularly want to thank the handful of men at Wakulla who transcended the roles of “research participants” to become my friends and collaborators. -

Journal 23,4 Layout 1

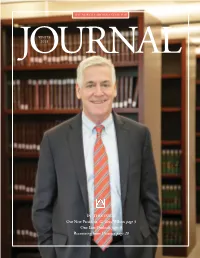

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR WINTER JOURNAL2018 IN THIS ISSUE Our New President, G. Gray Wilson page 5 One Last Outlook page 8 Recovering from Disaster page 20 THE NORTH CAROLINA STATE BAR JOURNAL FEATURES Winter 2018 Volume 23, Number 4 5 An Interview with the State Bar’s New Editor President, G. Gray Wilson Jennifer R. Duncan 8 One Last Outlook—An Interview with Retiring Executive Director L. Thomas Lunsford II © Copyright 2018 by the North Carolina State Bar. All rights reserved. Periodicals 12 Summer Session: The Morganton postage paid at Raleigh, NC, and additional Decisions, 1847-1861 offices. Opinions expressed by contributors By Thomas P. Davis are not necessarily those of the North Carolina State Bar. POSTMASTER: Send 18 Counselor address changes to the North Carolina State By Ryan Stowe Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. The North Carolina Bar Journal invites the 20 Recovering from Disaster: “Helpers” submission of unsolicited, original articles, in the Legal Community Respond essays, and book reviews. Submissions may By Mary Irvine be made by mail or email (jduncan@ ncbar.gov) to the editor. Publishing and edi- 22 Running Man torial decisions are based on the Publications By G. Gray Wilson Committee’s and the editor’s judgment of the quality of the writing, the timeliness of the article, and the potential interest to the readers of the Journal. The Journal reserves the right to edit all manuscripts. The North Carolina State Bar Journal (ISSN 10928626) is published four times per year in March, June, September, and December under the direction and supervision of the council of the North Carolina State Bar, PO Box 25908, Raleigh, NC 27611. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Elizabeth Kai Hinton

CURRICULUM VITAE Elizabeth Kai Hinton Department of History Department of African and African American Studies Harvard University Robinson Hall, Room 213 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT July 2014 - Assistant Professor Department of History Department of African and African American Studies Harvard University September 2012- July 2014 Assistant Professor Department of Afroamerican and African Studies University of Michigan Postdoctoral Scholar University of Michigan Society of Fellows EDUCATION Ph.D. with distinction, 2013 United States History Columbia University, New York, NY Dissertation Title: “From Social Welfare to Social Control: Federal War in American Cities, 1968-1988” Advisor: Eric Foner Committee: Ira Katznelson (Second Reader), Alan Brinkley, Mae Ngai, Heather Ann Thompson (Outside Reader) M.Phil May 2008 United States History; Politics, Culture and the African Diaspora Columbia University, New York, NY M.A. May 2007 United States History Columbia University, New York, NY Thesis: “The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement: Black Power and Labor, 1963-1968” Advisor: Manning Marable B.A. May 2005 American Studies Minor: Caribbean Studies Gallatin School of Individualized Study New York University, New York, NY Magna Cum Laude Full CV Available Upon Request 2 PUBLICATIONS Books in Contract From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: Race and Federal Policy in American Cities (with Harvard University Press). Books Editor, with Manning Marable. The New Black History: Revisiting the Second Reconstruction. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan Critical Black Studies Book Series, 2011). Book Chapters “The Black Bolsheviks: Detroit Revolutionary Union Movements and Shop Floor Organizing,” in The New Black History: Revisiting the Second Reconstruction (New York: Palgrave Macmillan Critical Black Studies Book Series, 2011). -

Sports and the Rhetorical Construction of the Citizen-Consumer

THE SPORTS MALL OF AMERICA: SPORTS AND THE RHETORICAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE CITIZEN-CONSUMER Cory Hillman A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Committee: Dr. Michael Butterworth, Advisor Dr. David Tobar Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Clayton Rosati Dr. Joshua Atkinson © 2010 Cory Hillman All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Michael Butterworth, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation was to investigate from a rhetorical perspective how contemporary sports both reflect and influence a preferred definition of democracy that has been narrowly conflated with consumption in the cultural imaginary. I argue that the relationship between fans and sports has become mediated by rituals of consumption in order to affirm a particular identity, similar to the ways that citizenship in America has become defined by one’s ability to consume under conditions of neoliberal capitalism. In this study, I examine how new sports stadiums are architecturally designed to attract upper income fans through the mobilization of spectacle and surveillance-based strategies such as Fan Code of Conducts. I also investigate the “sports gaming culture” that addresses advertising in sports video games and fantasy sports participation that both reinforce the burgeoning commercialism of sports while normalizing capitalism’s worldview. I also explore the area of licensed merchandise which is often used to seduce fans into consuming the sports brand by speaking the terms of consumer capitalism often naturalized in fan’s expectations in their engagement with sports. Finally, I address potential strategies of resistance that rely on a reassessment of the value of sports in American culture, predicated upon restoring citizens’ faith in public institutions that would simultaneously reclaim control of the sporting landscape from commercial entities exploiting them for profit. -

Dr. Heather Ann Thompson

DR. HEATHER ANN THOMPSON Associate Professor of History Department of African American Studies Department of History Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 email: [email protected] PERSONAL: • Date of birth: August 17, 1963 • Birthplace: Lawrence, Kansas EDUCATION: • Princeton University. American History, Ph.D., 1995 • The University of Michigan. History, M.A. (With Distinction), 1987 • The University of Michigan. History, B.A. (Highest Honors), 1987 PUBLICATIONS: Books: • Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy (Pantheon Books, to press 2011) • Thompson, ed. Speaking Out With Many Voices: Documenting American Activism and Protest in the 1960s and 1970s, ( July, 2009) • Thompson, Whose Detroit: Politics, Labor and Race in a Modern American City (Cornell University Press, 2001) Articles in Refereed Journals: • “Rethinking Working Class Struggle through the Lens of the Carceral State: Toward a Labor History of Inmates and Guards.” Labor: Studies in the Working Class History of the Americas (forthcoming: Fall, 2011) • “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline and Transformation in Postwar American History,” Journal of American History. (December, 2010) • “Making a Second Urban History." Essay collection commemorating the publication of Arnold Hirsch's, Making a Second Ghetto in the Journal of Urban History (May, 2003) • ”Another War at Home: Reexamining Working Class Politics in the 1960s,” MidAmerica. (September 2000) • "Rethinking the Politics of White Flight in the Postwar City: Detroit, 1945-1980," The Journal of Urban History. (January, 1999) 2 Chapters in Books: • “America's Second Prison Crisis: Locating the Origins of Today's Race to Incarcerate, and the Key to its End, in the Long 20th Century.” In The Problem of Punishment (forthcoming University of Virginia Press) • “Blinded by a “Barbaric” South: Prison Horrors, Inmate Abuse and the Ironic History of Penal Reform in the Postwar United States” in Lassiter and Crespino, ed. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

ANNUAL REPORT November 2013

PRISON POLICY INITIATIVE 2012-2013 ANNUAL REPORT November 2013 PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061 http://www.prisonpolicy.org 1 (413) 527-0845 Table of contents Executive Director's letter ......................................................................................................1 Who we are .............................................................................................................................5 Campaign updates Protecting our democracy from mass incarceration ..........................................................6 Bringing fairness to the prison and jail phone industry ....................................................8 Protecting letters from home in local jails ......................................................................10 Fighting against overreaching and ineffective geography-based penalties ....................11 Research Clearinghouse and Legal Resources for Incarcerated People ..........................13 Seizing timely opportunities to advance justice reform ...................................................14 Supporting our work ............................................................................................................16 Prison Policy Initiative budget report for 2012-2013 year .........................................17 1 Executive Director’s letter Dear friends and supporters, The non-profit, non-partisan I’m thrilled to share our first annual report that recaps our most recent Prison Policy Initiative produces accomplishments. In this report (see pages 6-15), we