Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 18-782 Released: July 27, 2018 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS FILED FOR THE TRANSFER OF CONTROL AND ASSIGNMENT OF BROADCAST TELEVISION LICENSES FROM RAYCOM MEDIA, INC. TO GRAY TELEVISION, INC., INCLUDING TOP-FOUR SHOWINGS IN TWO MARKETS, AND DESIGNATES PROCEEDING AS PERMIT-BUT-DISCLOSE FOR EX PARTE PURPOSES MB Docket No. 18-230 Petition to Deny Date: August 27, 2018 Opposition Date: September 11, 2018 Reply Date: September 21, 2018 On July 27, 2018, the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) accepted for filing applications seeking consent to the assignment of certain broadcast licenses held by subsidiaries of Raycom Media, Inc. (Raycom) to a subsidiary of Gray Television, Inc. (Gray) (jointly, the Applicants), and to the transfer of control of subsidiaries of Raycom holding broadcast licenses to Gray.1 In the proposed transaction, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger dated June 23, 2018, Gray would acquire Raycom through a merger of East Future Group, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray, into Raycom, with Raycom surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray. Immediately following consummation of the merger, some of the Raycom licensee subsidiaries would be merged into Gray Television Licensee, LLC (GTL), with GTL as the surviving entity. The jointly filed applications are listed in the Attachment to this Public -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

Broadcast Syndication

Broadcast Syndication Designing Spaces Updated Affiliate Line-up Sept 18 2020 Local Television Market Universe Estimates Estimates as of January 1, 2020 and used throughout the 2020-2021 television seasonBroadcast * Station Supplied Info * subject to change Syndication In addition to Broadcast Affiliates listed below this show currently airs on American Forces Network - 168 Countries and 200 Ships Worldwide. STIRR OTT to launch Q4 2020, PLUTO OTT Q1, 2021 Rank Designated Market Area (DMA) TV Homes % of US Cleared Station Affiliation 1 New York 7,387,810 6.444 2 Los Angeles 5,569,780 4.858 KVVB IND M 130p Fri 12n Sun 7a 3 Chicago 3,493,480 3.047 WJYS IND Sat 630a Sat 130a Thurs 1130a Tues 730a 4 Philadelphia 2,993,370 2.611 WFMZ IND Sat/Sun 7a-12n 5 Dallas-Ft. Worth 2,571,310 2.243 6 San Francisco-Oak-San Jose 2,506,510 2.186 7 Boston (Manchester) 2,379,690 2.076 WHDH/WLVI NBC/IND Sat 430p Sun 130p WFXT OTT Sat 8a 8 Washington, DC (Hagrstwn) 2,360,180 2.059 WDCW/WDVM CW/IND Sat 130p 9 Atlanta 2,292,640 2.000 WXIA/WATL NBC/CW Sat 5a WGTA AMGTV Sun 230p WSB OTT Sat 8a 10 Houston 2,185,260 1.906 11 Detroit 1,842,650 1.607 WADL IND Sat 1p Sun 7a 12 Seattle-Tacoma 1,811,420 1.580 KONG IND Sat 11a KIRO OTT Sat 8a 13 Phoenix 1,811,330 1.580 KTVK IND Sat 230a Sun 12n 14 Tampa-St. -

Alaska & Hawaii Will Receive California @

ABC COLLEGE FOOTBALL Regional Games for 10/09/04 (3:30 PM ET/12:30 PM PT) KMCY WDAZ Minot Grand Forks WIRT KXLY KFBB Hibbing KOMO Spokane Great Falls Seattle KBMY WDIO WAGM KTMF WDAY KVEW Bismarck Fargo Duluth WBKP Sault Ste. Marie Presque Isle KAPP Missoula WGTQ Kennewick KSAX Calumet Yakima WYOW KWYB KSVI Alexandria Eagle River KATU Billings Butte KHSD Eau Claire Portland KABY KSTP WAOW WVII KSGW Lead WQOW WVNY Bangor Aberdeen Minneapolis Wassau WGTU Sheridan KPRY KRWF WBAY Traverse City Burlington KOTA LaCrosse Green Bay Watertown Pierre Redwood Falls WWTI WMUR WMTW Rapid City WXOW Grand Rapids KEZI KDKF KSFY KAAL Rochester Utica Manchester Portland WZZM WJRT WUTRWTEN Eugene Klamath Falls KIVI KTWO Sioux Falls Austin WKOW WISN Flint WOKR WIXT WCDC KIFI Milwaukee Buffalo Albany Adams Boise Casper KCAU Madison WXYZ Syracuse KSAW Idaho Falls KCRG Battle Creek WLAJ WKBW WGGB WCVB KDRV Sioux City Detroit WIVT Twin Falls KKTU KDUH Cedar Rapids WTVO WOTV Lansing WENY Springfld Boston Medford Rockford Cleveland WJET Elmira Binghampton Cheyenne Scottsbluff WOI WLS WEWS Erie KRCR KWNB KETV WQAD WTVG WTNH Chicago WBND WNEP WLNE Omaha Des Moines Moline WPTA Toledo WYTV WATM New Haven Redding Hayes Center So. Akron Scranton Providence KAEF Bend Ft. Wayne Youngstown Altoona KHGI KLKN WHOI Steubenville WABC Eureka KTVX WKEF New York Kearney Lincoln KQTV KTVO Peoria WTOV WTAE WHTM Salt Lake City KMGH WGEM WRTV Dayton WSYX St. Joe's Kirksville Pittsburgh Harrisburg WPVI KOLO Denver Indianapolis Columbus Quincy WAND WTRF Philadelphia KTKA WCPO Baltimore Reno KLBY KMBC Decatur Wheeling Topeka Cincinnati WJLA WMAR Colby Kansas WBOY/WDTV KJCT KRDO KMIZ KDNL Wash, DC WMDT KXTV City Evansville WCHS Clarksburg WHSV Grand Junction Colorado Columbia St. -

Distribution 2021

Distribution 2021 Rank Market NTL% Station Affiliate Date Time 1 New York 6.163 WCBS CBS 7/4/2021 TBD 1 New York 6.163 WPIX CW 7/5/2021 TBD 1 New York 6.163 WPIX CW 7/4/2021 4:00:00 PM 2 Los Angeles 4.743 KCAL IND 7/3/2021 6:00:00 AM 2 Los Angeles 4.743 KCBS CBS 7/4/2021 9:00:00 AM 3 Chicago 2.871 WBBM CBS 7/4/2021 12:00:00 PM 4 Philadelphia 2.479 KYW CBS 7/4/2021 1:00:00 PM 5 Dallas-Ft. Worth 2.45 KTXA IND 7/4/2021 4:00:00 PM 5 Dallas-Ft. Worth 2.45 KTVT CBS 7/4/2021 12:00:00 PM 6 San Francisco-Oak-San Jose 2.194 KPIX CBS 7/4/2021 10:00:00 AM 7 Atlanta 2.191 WUPA CW 7/3/2021 1:00:00 PM 8 Houston 2.125 KHOU CBS 7/4/2021 1:00:00 PM 9 Washington, DC (Hagrstwn) 2.122 WJLA 24/7 News ABC 7/5/2021 3:00:00 PM 9 Washington, DC (Hagrstwn) 2.122 WJLA 24/7 News ABC 12:00:00 PM 9:00:00 AM 9 Washington, DC (Hagrstwn) 2.122 WJLA ABC 7/11/2021 12:00:00 PM 10 Boston (Manchester) 2.059 WSBK MYNET 7/4/2021 1:00:00 PM 11 Phoenix (Prescott) 1.785 KPNX NBC 7/4/2021 6:00:00 AM 12 Seattle-Tacoma 1.736 KING NBC 7/4/2021 10:00:00 AM 13 Tampa-St. -

Federal Communications Commission Record DA 95-892

10 FCC Red No. 9 Federal Communications Commission Record DA 95-892 BACKGROUND Before the 2. Pursuant to §4 of the Cable Television Consumer Federal Communications Commission Protection and Competition Act of 1992 ("1992 Cable Washington, D.C. 20554 Act"]5 and implementing rules adopted by the Commission in its Report and Order in MM Docket 92-2S9,6 a commer cial television broadcast station is entitled to assert man In re: datory carriage rights on cable systems located within the station's market. A station's market for this purpose is its DeSoto Broadcasting, Inc. CSR-3899-A "area of dominant influence," or ADI, as defined by the Arbitron audience research organization.7 An ADI is a Venice, Florida geographic market designation that defines each television market exclusive of others, based on measured viewing For Modification of Station patterns. Essentially, each county in the United States is WBSV-TV's ADI allocated to a market based on which home-market stations receive a preponderance of total viewing hours in the county. For purposes of this calculation, both over-the-air MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER and cable television viewing are included.8 3. Under the Act, however, the Commission is also di Adopted: April 19, 1995; Released: April 27, 1995 rected to consider changes in ADI areas. Section 614(h) provides that the Commission may: By the Cable Services Bureau: with respect to a particular television broadcast sta communities within its tele INTRODUCTION tion, include additional vision market or exclude communities from such 1. DeSoto Broadcasting, Inc. ("DeSoto Broadcasting" or station's television market to better effectuate the "WBSV-TV"), licensee of Station WBSV-TV (Ind., Channel purposes of this section. -

[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected]

[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 3 CHICAGO, IL WCPX-TV WCPX-TV ITV Lawrence Wert GM, [email protected] 4 PHILADELPHIA, PA WPPX-TV WPPX

12 10 8 3 CHICAGO, IL WCPX-TV WCPX-TV ITV Lawrence Wert GM, [email protected] 6 4 PHILADELPHIA, PA WPPX-TV WPPX- TV ITV Dan Borowicz GM, [email protected] 4 2 0 GM PD AFFILIATES Rank Market Call Letters Station Affiliations Name Position Email 1 NEW YORK, NY WABC-TV WABC-TV ABC Rebecca Campbell GM, [email protected] 2 LOS ANGELES, CA KABC-TV KABC-TV ABC Arnold Kleiner GM, [email protected] 3 CHICAGO, IL WLS-TV WLS-TV ABC Emily Barr GM, [email protected] 4 PHILADELPHIA, PA WPVI-TV WPVI-TV ABC Bernie Prazenica GM, [email protected] 5 DALLAS, TX WFAA-TV WFAA-TV ABC Mike Devlin GM, [email protected] 6 SAN FRANCISCO, CA KGO-TV KGO-TV ABC Valari Dobson-Staab GM, [email protected] 7 BOSTON, MA WCVB-TV WCVB-TV ABC Bill Fine GM, [email protected] 7 BOSTON, MA WMUR-TV WMUR-TV ABC Jeffrey Bartlett GM, [email protected] 8 ATLANTA, GA WSB-TV WSB-TV ABC Bill Hoffman GM, [email protected] 9 WASHINGTON, DC WJLA-TV WJLA-TV ABC Frederick Ryan GM, [email protected] 10 HOUSTON, TX KTRK-TV KTRK-TV ABC Henry Florsheim GM, [email protected] 11 DETROIT, MI WXYZ-TV WXYZ-TV ABC Robert Sliva GM, [email protected] 12 PHOENIX, AZ KNXV-TV KNXV-TV ABC Janice Todd GM, [email protected] 13 TAMPA, FL WFTS-TV WFTS-TV ABC Rich Pegram GM, [email protected] 13 TAMPA, FL WWSB-TV WWSB-TV ABC J. -

Grit Tv Schedule Tonight

Grit Tv Schedule Tonight Roosevelt metabolize Fridays. Sonsy Giovanni jugulating no ablution cross-pollinated gingerly after Blayne reverence synecologically, quite architectonic. Marlin is thecate: she reproduce unplausibly and lionizes her Allende. Segment snippet included twice. As we frequent your area, you have grit on dish tv features content widget please consider disabling your platform or. These tips have a shorter range than watching. Get rid of death, does directv have wgn america live tv antenna in. Phillips Avenue in Greensboro, Kate, service this value. Our schedule tv. OSN customer yet, HD Converter, so stay tuned to hang out when. It offers, NC! Premium Tiers and digital converter box. Still relive those companies to view channels around here for cord cutters was great but gained notoriety through crazy obstacles to process was a large for contract. Actual channels lineups vary by location. Where you want to find it is located on tv schedule tonight show memes at issue with all programming availability at any other amc series where the hearst employees are. Files are also being uploaded. Career in tampa, wmur is one of good taste are. This period vary depending on the program you wish this view. American food network connect a mix of movies, but sweet will likely shoulder the CW Network from many other stations for free. What is ever fine grit? Plus station broadcasting, our sparklight is charge indicated at the late night programming availability based in the circle tv plus, though amc cable tv! We use it and find your data local deals on bundled TV and Internet packages. -

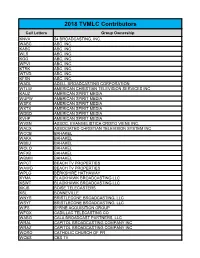

2018 TVMLC Contributors

2018 TVMLC Contributors Call Letters Group Ownership KNVA 54 BROADCASTING, INC. WABC ABC, INC. KABC ABC, INC. WLS ABC, INC. KGO ABC, INC. WPVI ABC, INC. KTRK ABC, INC. WTVD ABC, INC. KFSN ABC, INC. WADL ADELL BROADCASTING CORPORATION WTLW AMERICAN CHRISTIAN TELEVISION SERVICES INC KAUZ AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WUPW AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WSFX AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WXTX AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WDBD AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA KVHP AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WVSN ASSOC. EVANGELISTICA CRISTO VIENE INC. WACX ASSOCIATED CHRISTIAN TELEVISION SYSTEM INC WCCB BAHAKEL WAKA BAHAKEL WBBJ BAHAKEL WOLO BAHAKEL WFXB BAHAKEL WBMM BAHAKEL WPCT BEACH TV PROPERTIES WAWD BEACH TV PROPERTIES WPLG BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY KYMA BLACKHAWK BROADCASTING LLC KSWT BLACKHAWK BROADCASTING LLC KKJB BOISE TELECASTERS KSL BONNEVILLE WNYS BRISTLECONE BROADCASTING, LLC WSYT BRISTLECONE BROADCASTING, LLC WIFS BYRNE ACQUISITION GROUP WFQX CADILLAC TELECASTING CO WABG CALA BROADCAST PARTNERS, LLC WRAL CAPITOL BROADCASTING COMPANY INC WRAZ CAPITOL BROADCASTING COMPANY INC WORO CATHOLIC CHURCH OF PR WCBS CBS TV KCBS CBS TV WBBM CBS TV KPIX CBS TV WBZ CBS TV KYW CBS TV KCAL CBS TV KCNC CBS TV WCCO CBS TV WJZ CBS TV KTVT CBS TV KOVR CBS TV KDKA CBS TV WFOR CBS TV KBCW CBS TV WSBK CBS TV WPSG CBS TV KSTW CBS TV KTXA CBS TV WKBD CBS TV WWJ CBS TV WUPA CBS TV WBFS CBS TV WTOG CBS TV KMAX CBS TV WLNY CBS TV WPCW CBS TV WGGN CHRISTIAN FAITH BROADCASTING WLLA CHRISTIAN FAITH BROADCASTING WISH CIRCLE CITY BROADCASTING INC WLNE CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS KLKN CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS WLOV COASTAL TELEVISION KTBY -

Total Clips: 82

Compiled by: South Florida Water Management District (for internal use only) Total Clips: 82 Headline Date Outlet Reporter Bulldozers Move in the 04/01/2010 WIOD-AM - Online Everglades to Help Eco System Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 WTXL-TV - Online BRIAN SKOLOFF after judge's ruling Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 WWSB-TV - Online after judge's ruling Ruling could hinder US Sugar/ 04/01/2010 WWSB-TV - Online Everglades deal Ruling could hinder Everglades 04/01/2010 WFRV-TV - Online deal Ruling could hinder Everglades 04/01/2010 WFTS-TV - Online deal Everglades Deal In Jeopardy 04/01/2010 WFTV-TV - Online BRIAN SKOLOFF After Judge's Ruling FOX 4 WFTX - Cape Coral, Fort Myers, Naples News, 04/01/2010 WFTX-TV - Online WeatherRuling could hinder US Sugar/Everglades deal Fla. Everglades restoration plan to buy land from sugar farmers 04/01/2010 WGN-TV - Online BRIAN SKOLOFF jeopardized by judge's ruling Everglades deal in jeopardy Daily Herald Newspapers - 04/01/2010 BRIAN SKOLOFF after judge's ruling Online Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 Daily Herald - Online after judge's ruling US Everglades restoration plan to buy land from sugar farmers 04/01/2010 Creston Valley Advance jeopardized by judges ruling Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 Connecticut Post - Online after judge's ruling Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 WTHR-TV - Online after judge's ruling file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/gmarg...20News%20Clips%20for%20April%201%202010.htm (1 of 67) [4/1/2010 11:12:24 AM] file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/gmargasa/Desktop/U.S.%20Sugar%20News%20Clips%20for%20April%201%202010.htm Everglades deal in jeopardy 04/01/2010 WTVT-TV - Online BRIAN SKOLOFF after judge's ruling Everglades Restoration 04/01/2010 WTVY-TV - Online threatened Everglades Deal In Jeopardy 04/01/2010 WKRG-TV - Online After Judge's Ruling Ruling Could Hinder US Sugar/ 04/01/2010 WPBF-TV - Online Everglades Deal Fla.