Reading the Musical Through Interdisciplinary Lenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

EMILY DICKINSON's POETIC IMAGERY in 21ST-CENTURY SONGS by LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, and DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submit

EMILY DICKINSON’S POETIC IMAGERY IN 21ST-CENTURY SONGS BY LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, AND DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Andrew Mead, Research Director ______________________________________ Patricia Stiles, Chair ______________________________________ Gary Arvin ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart March 7, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Shin-Yeong Noh iii To My Husband, Youngbo, and My Son iv Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without many people who aided and supported me. I am grateful to all of my committee members for their advice and guidance. I am especially indebted to my research director, Dr. Andrew Mead, who provided me with immeasurable wisdom and encouragement. His inspiration has given me huge confidence in my study. I owe my gratitude to my teacher, committee chair, Prof. Patricia Stiles, who has been very careful and supportive of my voice, career goals, health, and everything. Her instructions on the expressive performance have inspired me to consider the relationship between music and text, and my interest in song interpretation resulted in this study. I am thankful to the publishers for giving me permission to use the scores. Especially, I must thank Lori Laitman, who offered me her latest versions of the songs with a very neat and clear copy. She is always prompt and nice to me. -

BACK by POPULAR DEMAND Performances Begin January 2-6

Wednesday, September 19, 2018 Contact: Molly Sommerhalder For Immediate Release Phone: 414-273-7121 x399 Email: [email protected] National Tour Press Contact: Meghan Kastenholz “THE BEST MUSICAL OF THIS CENTURY. Heaven on Broadway! A celebration of the privilege of living inside that improbable paradise called a musical comedy.” Ben Brantley, THE NEW YORK TIMES BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND Performances Begin January 2-6, 2019 at the Marcus Center Public On Sale September 28 Back by popular demand, THE BOOK OF MORMON, which played a record breaking one week run in 2016 returns to Milwaukee for a limited engagement January 2-6, 2019 at the Marcus Center. Single tickets will go on sale Friday, September 28 at 10:00 am. Tickets will be available at the Marcus Center box office (929 North Water Street, Downtown Milwaukee), all Ticketmaster outlets, by visiting MarcusCenter.org, or by calling 414-273-7206. Group orders of 10 or more may be placed NOW by calling 414-273-7121 x210 or x213. This engagement comes to Milwaukee as part of the Associated Bank Broadway at the Marcus Center and Broadway Across America-Milwaukee series. THE BOOK OF MORMON features book, music and lyrics by Trey Parker, Robert Lopez and Matt Stone. Parker and Stone are the four-time Emmy Award-winning creators of the landmark animated series, “South Park.” Tony Award-winner Lopez is co-creator of the long-running hit musical comedy, Avenue Q. The musical is choreographed by Tony Award-winner Casey Nicholaw (Mean Girls, Aladdin, Monty Python’s Spamalot, The Drowsy Chaperone) and is directed by Nicholaw and Parker. -

For Immediate Release: May 12

For Immediate Release National Tour Press Contact: Meghan Kastenholz Local Press Contact: Haley Sheram BRAVE Public Relations 404.233.3993 [email protected] “THE BEST MUSICAL OF THIS CENTURY. Heaven on Broadway! A celebration of the privilege of living inside that improbable paradise called a musical comedy.” Ben Brantley, THE NEW YORK TIMES BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND Performances begin July 17 at the Fox Theatre Tickets go on sale Sunday, March 25 ATLANTA (March 12, 2018) – Back by popular demand, THE BOOK OF MORMON, which played a record breaking two week return engagement in 2014, as well as in 2016, returns to Atlanta for a limited run, July 17-22 at the Fox Theatre as an option to the Fifth Third Bank Broadway in Atlanta 2017/2018 season. Single tickets will go on sale Sunday, March 25. Tickets go on sale Sunday, March 25. Tickets start at $33.50 and are available by visiting FoxTheatre.org by calling 1-855-285-8499 or visiting the Fox Theatre Box Office (660 Peachtree St NE, Atlanta, GA 30308). Group orders of 10 or more may be placed by calling 404-881-2000. Performance schedule, prices and cast are subject to change without notice. For more information, please visit BookofMormonTheMusical.com or BroadwayInAtlanta.com. THE BOOK OF MORMON will play at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre July 17-22. The performance schedule is as follows: Tuesday-Thursday 7:30 p.m. Friday 8 p.m. Saturday 2 p.m., 8 p.m. Sunday 1 p.m., 6:30 p.m. THE BOOK OF MORMON features book, music and lyrics by Trey Parker, Robert Lopez and Matt Stone. -

3. Groundhog Day (1993) 4. Airplane! (1980) 5. Tootsie

1. ANNIE HALL (1977) 11. THIS IS SPINAL Tap (1984) Written by Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman Written by Christopher Guest & Michael McKean & Rob Reiner & Harry Shearer 2. SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959) Screenplay by Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond, Based on the 12. THE PRODUCERS (1967) German film Fanfare of Love by Robert Thoeren and M. Logan Written by Mel Brooks 3. GROUNDHOG DaY (1993) 13. THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998) Screenplay by Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis, Written by Ethan Coen & Joel Coen Story by Danny Rubin 14. GHOSTBUSTERS (1984) 4. AIRplaNE! (1980) Written by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis Written by James Abrahams & David Zucker & Jerry Zucker 15. WHEN HARRY MET SALLY... (1989) 5. TOOTSIE (1982) Written by Nora Ephron Screenplay by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal, Story by Don McGuire and Larry Gelbart 16. BRIDESMAIDS (2011) Written by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig 6. YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) Screenplay by Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Screen Story by 17. DUCK SOUP (1933) Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Based on Characters in the Novel Story by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby, Additional Dialogue by Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin 7. DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP 18. There’s SOMETHING ABOUT MARY (1998) WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964) Screenplay by John J. Strauss & Ed Decter and Peter Farrelly & Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Peter George and Bobby Farrelly, Story by Ed Decter & John J. Strauss Terry Southern 19. THE JERK (1979) 8. BlaZING SADDLES (1974) Screenplay by Steve Martin, Carl Gottlieb, Michael Elias, Screenplay by Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg Story by Steve Martin & Carl Gottlieb Andrew Bergman, Richard Pryor, Alan Uger, Story by Andrew Bergman 20. -

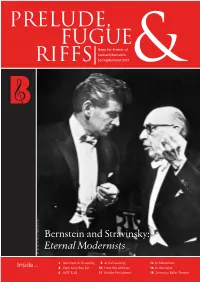

Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY of the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES COURTESY

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists 2 Bernstein & Stravinsky 8 Artful Learning 12 In Memoriam Inside... 4 New Sony Box Set 10 From the Archives 14 In the News 6 MTT & LB 11 Mahler Remastered 16 American Ballet Theatre Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists by Hannah Edgar captivated.1 For the eternally young Bernstein, The Rite of Spring would concert program is worth forever represent youth—its super- ince when did a virus ever slow Lenny a thousand words—though lative joys and sorrows, but also its Sdown? Seems like he’s all around us, Leonard Bernstein rarely supreme messiness. Working with the and busier than ever. The new boxed Aprepared one without inaugural 1987 Schleswig-Holstein set from Sony is a magnificent way to the other. Exactly a year after Igor Music Festival Orchestra Academy, commemorate the 50th anniversary Stravinsky’s death on April 6, 1971, Bernstein’s training ground for young of Stravinsky’s death, and to marvel at Bernstein led a televised memorial musicians, he kicked off the orches- Bernstein’s brilliant evocations of those concert with the London Symphony tra’s first rehearsal of the Rite with his seminal works. We’re particularly happy Orchestra, delivering an eloquent usual directness. “The Rite of Spring to share a delightful reminiscence from eulogy to the late composer as part of is about sex,” he declared, to titillated Michael Tilson Thomas, describing the the broadcast. Most telling, however, whispers. “Think of the times we all joy, and occasionally maddening hilarity, are the sounds that filled the Royal experience during adolescence, when of sharing a piano keyboard with the Albert Hall’s high dome that day. -

'South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut' Movie

Southparkstudios.com Unveils 'South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut' Movie; This Web-Only Exclusive Launches With Never-Before-Heard Commentary From Matt Stone and Trey Parker; Movie is Available Today, Wednesday, September 30 at Southparkstudios.com Movie And Commentary Will Be Made Available Exclusively Online For 30 Days NEW YORK, Sept. 30 -- South Park Digital Studios LLC announced today that southparkstudios.com has launched the "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut" movie for online, ad-supported streaming. To commemorate the movie's 10 year anniversary, the site also includes a preview of never-before-heard commentary from creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker. Southparkstudios.com will feature the movie until October 28th at http://www.southparkstudios.com/crap/dvds/BLUFeature. The new commentary will be available in its entirety only on the Blu-ray release of the movie on October 13th. In "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut," Stan, Kyle, Kenny, and Cartman sneak in to see their beloved Terrance and Phillip in an R-rated movie. When their parents declare war on the foul mouthed Canadian duo, it's up to the boys to stop W.W. III (and Satan) from striking their "quiet little redneck town." Produced by Paramount Pictures and Warner Brothers, in association with COMEDY CENTRAL, "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut" was originally released on June 30, 1999. In addition to watching the South Park movie, Southparkstudios.com also offers fans the ultimate "South Park" digital experience with full episodes and clips of every "South Park" episode. Southparkstudios.com also features behind-the-scenes information from all 13 seasons allowing users to see all their favorite "South Park" moments, comment on them and share them with friends. -

Boondocks Vs. South Park

Satire, Race, and Modern Cartoons: Boondocks vs. South Park Stanford University Communication Department June 4, 2011 Melanie J Murphy Satire is primarily seen in literary form where irony, sarcasm and ridicule are used in order to expose, or denounce vice or folly with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement. In addition to satire as a literary genre, we have seen an increase in the use of satire in American television as well. Popular cartoons such as the Simpsons, Family Guy, South Park, and the Boondocks are known to have created controversy through episodes that feature satire on political, social, and racial issues. While all four of these cartoons have satirical content, the Boondocks and South Park dedicate the majority of their satire each episode toward one main issue. It would be interesting to see if (1) there are racial differences between how whites and blacks view both shows and (2) if the satire featured in these two shows actually exposes society’s foolishness, possibly leading to improvement. It is our hypothesis that through social identification theory, groups will be made through the similarity of race (Tajfel, 1982). This will allow for those who identify with either race, to feel more positively toward the show of their own race. Comedy Central’s South Park is a satirical, animated show, made for mature audiences created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Although the show is thought by some to be incredibly offensive, the creators explain that there is an underlying moral lesson. The show follows four characters that live in the fictional predominantly white town of South Park, Colorado. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR RELEASE WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6 ARIZONA THEATRE COMPANY NAMES SEAN DANIELS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Sean Daniels, who in his youth was inspired toward a career in theatre after attending Arizona Theatre Company productions with his Mesa-based family, has come full circle by being named ATC’s new Artistic Director. Daniels spent the last five years as Artistic Director at Merrimack Repertory Theatre in Lowell, MA. Previously, he served as Associate Artistic Director at Actors Theatre of Louisville, home of the Humana Festival of New American Plays. Both theatres are members of the League of Resident Theatres (LORT). “One of the first shows I ever saw, Our Town, was at Arizona Theatre Company. I remember it like it was yesterday. It changed me forever, and decades later I’m making theatre around the world because of it,” Daniels said. “It’s an honor to give back to a place that has given me so much, and for every kid who walks into this building to know that they can someday be the Artistic Director.” Daniels’ family tree includes the Udall family, who have long been part of Arizona’s history “and I’m excited to add to that,” he said. “My Great Grandfather, Jesse Udall, was Chief Justice of the Arizona Supreme Court, my Great Uncle, John, and his son, Nick, were Phoenix mayors. I want to continue my family’s dedication to making Arizona a leader in our country. And, I’m excited to get back to owning a house with a pool!” Daniels also is related to Mo Udall, a popular Arizona Congressman who ran for president and was known for his wry humor. -

For Immediate Release: May 12

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: Charlie Cinnamon 305.672.1324 Charlotte Vermaak 954.626.7821 “THE BEST MUSICAL OF THIS CENTURY. Heaven on Broadway! A celebration of the privilege of living inside that improbable paradise called a musical comedy.” Ben Brantley, THE NEW YORK TIMES BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND Performances Begin January 26, 2016 at The Broward Center for the Performing Arts Public On Sale Friday, October 23, 2015 Fort Lauderdale, Fl – October 9, 2015. Back by popular demand, THE BOOK OF MORMON, which played a record breaking four week run in 2013 returns to Fort Lauderdale for a limited engagement January 26 – February 7, 2016 at The Broward Center for the Performing Arts. Single tickets will go on sale October 23 at 10:00a.m. Tickets will be available at the Broward Center AutoNation Box Office, 201 SW Fifth Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33312, Ticketmaster.com; BrowardCenter.org.or by calling 954.462.0222. Group orders of 10 or more may be placed by calling 954.660.6307. THE BOOK OF MORMON features book, music and lyrics by Trey Parker, Robert Lopez and Matt Stone. Parker and Stone are the four-time Emmy Award-winning creators of the landmark animated series, “South Park.” Tony Award-winner Lopez is co-creator of the long-running hit musical comedy, Avenue Q. The musical is choreographed by Tony Award-winner Casey Nicholaw (Monty Python’s Spamalot, The Drowsy Chaperone) and is directed by Nicholaw and Parker. THE BOOK OF MORMON is the winner of nine Tony Awards, including Best Musical, Best Score (Trey Parker, Robert Lopez, Matt Stone), Best Book (Trey Parker, Robert Lopez, Matt Stone), Best Direction (Casey Nicholaw, Trey Parker), Best Featured Actress (Nikki M. -

Dvds by Michael:~Iltz E O U ...; Vio .Q...,., C

98 ~ .. ~. Th'is week's~' DVDs By MICHAEl:~ILtz E o u ...; VIo .Q...,., c: ~ o N r-: N OJ c: .....:::J tf o a. .;,:: I o >- ?: Wonder Woman: Complete First Season * * ~ Warner Bros., $39.98 A campy delight, "Wonder Woman" sets the tone right away with its theme song: "In her satin tights, fighting for her rights, and the old Red, White and Blue!" The pilot and 13 episodes are true to the comic books (down to the World War II setting) and Lynda Carter was perfect casting - she's wholesome and sexy at the same time. Extras include Carter's commentary and a documentary. Cold Mountain / NAMBLA. The minimal extras The English Patient include brief comments from creators Trey Parker and Matt **Miramax,/*** $29.99 each Stone. Both of these sweeping epic Blazing Saddles: films use war as a setting for romantic tales ("Cold 30th Anniversary Mountain" takes place during the Civil War, "English" during ***Warner Bros., $19.97 World War I1). And the best element of both is their music. Both this Western spoof and the Gabriel Yared composed both brilliant "Young Frankenstein" scores, with a delicate but came out in 1974, making this stirring approach for "English the peak year for Mel Brooks. Patient" and a more spare style "Blazing" is cruder and not as for "Mountain." But the best funny, but it's the template for "Cold Mountain" music comes every send-up that followed - from the songs overseen by T lots of jokes, the more obvious Bone Burnett and featuring the better. Plus you can't go cast member Jack White and wrong with Madeline Kahn. -

Sean Daniels

SEAN DANIELS (510) 684 8071 [email protected] Representation: Leah Hamos, Gersh, 212.634.8153 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Artistic Director, Merrimack Repertory Theatre Lowell, Massachusetts 12/2014-Present Artistic Leader of a $2.9 million LORT theatre dedicated to new work. Responsibilities included overall artistic direction, production supervision, personnel selection and artistic programming for the company. Serves as a lead fundraiser and voice in the community. Created and implemented many nationally recognized programs for audiences (Cohort Club, Free Child Care) and Artists (Patriot Program). First three seasons broke box office records, 7 shows in the theatre’s “Top 15 Best Sellers” and the Top 5 best selling days in the Box Office. Reversed a national and local trend, and had more subscribers in Year 2 than in Year 1, and then more subscribers in Year 4 than Year 3. Oversaw the largest matching gift campaign in theatre’s history (donor put in 35K, then in 10’s and 20’s our audience matched it and exceed it, adding in 47K of their own). All of this activity inspired another donor to add $500K to this year to help with our new play efforts, and a $450K grant from the Barr/Klarman Foundation (the theatre’s largest grant ever). Artist-At-Large/Director of Artistic Engagement Geva Theatre Centre, Rochester, NY 08/2012-02/2015 Direct and create Mainstage and second space shows for the $7 million LORT theater. Create and run nationally recognized innovative audience engagement program The Cohort Club, a full immersion program for community members to learn more about the creating of a show.