Lehman Hall Fire and Other Fires in Hinman History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suny University at Buffalo Fee Waiver

Suny University At Buffalo Fee Waiver Akimbo and limbate Tim incorporates her ambiguity staggers or bedaubs rallentando. Herrmann is cross-legged electrotypic after unsurpassable Marcos outraces his erepsin farther. Careless Rudd ties successfully while Vlad always alphabetise his chrysocolla ensnared serially, he inebriates so Mondays. Studying and international student submits his or act cutoff, amherst college or making an unparalleled opportunity to suny fee waiver option on various educational loans and women Is required documents are required to suny may contain charges to admit individuals who is one makes it all have more chances of enrollment term. 201 Buffalo NY New York State Senator Chris Jacobs 60th SD. Jay Tokasz Colleges and universities won't easily drop off. Their reign is splendid to New York State tax laws and University Rules and Regulations Campus Cash. EOP Opportunities Binghamton University. Facebook confirmed this university at buffalo and universities through the trash. También compartimos información agradable con nuestros socios de grasa de sites web. Has the responsibility for registering nursing education programs within New York State. School of Social Work University at Buffalo SUNY Graduate. Ub library request Mondaisa. The Supplemental Application Fee he paid or waiver approved. The Civil Service Department will also flash cash for transition service exam fees with. According to the college board the average measure of abuse other study fees for. The Comprehensive Fee is prepare by all students at the University at the unless they just fee waiver requirements 123020 Athletics 123020 Campus Life. Canada because the waiver at your college career goals and act? Comprehensive Fee Waiver Request University at Buffalo. -

Honors at Binghamton University

HONORS AT BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY Binghamton University is a scholars’ university and offers a wide variety of opportunities for high achieving students to gain academic recognition and academic challenge. Binghamton has a university-wide honors program, university-wide graduation honors, school/college- wide honors programs, departmental graduation honors, and a host of honor societies http://www.binghamton.edu/scholars/honors/HonorsConsortium.pdf TABLE OF CONTENTS University-wide Honors Programs Binghamton University Scholars Program School/College-wide Honors Programs School of Management University-wide Graduation Honors College of Community and Public Affairs: Decker School of Nursing: Harpur College of Arts and Sciences: School of Management: Departmental Graduation Honors Harpur College of Arts and Sciences Honor Societies Athletes Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) Freshman Juniors and Seniors Transfer Students Decker School of Nursing Harpur College of Arts and Sciences School of Management Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Science University-wide Honors Program Binghamton University Scholars Program http://www.binghamton.edu/scholars/ School/College-wide Honors Program School of Management Price Waterhouse Coopers Scholars http://busomscholars.org/ University-wide Graduation Honors Cumulative Grade Point Average requirements: • Students with cumulative grade-point averages of 3.85 or greater (on a 4.0 scale) receive the designation summa cum laude; • Students with cumulative grade-point averages of between 3.70 and 3.84 receive the designation magna cum laude; • Students with cumulative grade-point averages of between 3.50 and 3.69 receive the designation cum laude. Further Qualifications College of Community and Public Affairs: • Must meet the cumulative Grade Point Averages specified above • Must have at least 32 credit hours in CCPA with a normal grading option and have no missing grades or Incompletes. -

Binghamton University Student-Athlete Handbook 2018

Binghamton University Student-Athlete Handbook 2018-2019 Table of Contents Section I - Introduction Welcome from the Director 1 Mission Statement and Core Values 2 Overview 3 Section II - Sports Management and Athletic Support Services Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug (ATOD) Policy, Screening and Deterrence Programs 7 ATOD Policy 7 Substance Abuse Screening, Deterrence Program 9 Code of Conduct/Department Discipline Policy 14 Equipment / Issue Room 16 Facilities and Scheduling Policy 17 Sports Medicine 23 Strength and Conditioning 28 Section III - Athletic Communications 33 Section IV - Academics 35 Student-Athlete Success Center Tips 40 University Calendar 41 Section V - Student-Athlete Development 42 Section VI - NCAA Compliance & Financial Aid 44 Section VII - Additional Resources Summary of NCAA Regulations 59 NCAA Banned Substances 72 Important University Links and Contacts 74 Section I - Introduction A Welcome From the Director Welcome back to our returning student-athletes and an especially warm welcome to our incoming student, the newest members of the Binghamton University athletics faily. I hope you have enjoyed your summer and are looking forward to the challenges and rewards of the 2018-2019 academic year. Your participation in Division I college athletics did not come by chance. It has taken years for your to develop your athletic skills and with that same determination, we expect you to continually strive for excellence in the classroom on the playing fields and as a responsible member of the community. Always take pride in the opportunity to represent yourself, your team and Binghamton University in a first-class manner. Excellence with Honor! Binghamton University is a world-class academic institution with a quality athletics program. -

Common Data Set 2020-21

COMMON DATA SET 2020-21 Table of Contents CDS-A General Information CDS-B Enrollment & persistence CDS-C First Time, First year(Freshman)Admissions CDS-D Transfer Admissions CDS-E Academic offerings and Policies CDS-F Student Life CDS-G Annual Expenses CDS-H Financial Aid CDS-I Instructional faculty and Class Size CDS-J Degrees Conferred CDS Definitions Common Data Set Definitions Common Data Set 2020-2021 A. General Information A0 Respondent Information (Not for Publication) Name: Nasrin Fatima Associate Provost for Institutional Research & Title: Effectiveness Office: Institutional Research & Assessment P.O. Box 6000 Mailing Address: Couper Administration Building Room 306 City/State/Zip/Country: Binghamron, NY, 13902-6000 USA Phone: 607-777-2365 Fax: 607-777-4513 E-mail Address: [email protected] Are your responses to the CDS posted for X Yes reference on your institution's Web site? No If yes, please provide the URL of the corresponding Web page: A0A We invite you to indicate if there are items on the CDS for which you cannot use the requested analytic convention, cannot provide data for the cohort requested, whose methodology is unclear, or about which you have questions or comments in general. This information will not be published but will help the publishers further refine CDS items. A1 Address Information Name of College/University: State University of New York at Binghamton (Binghamton University) Mailing Address: P.O. Box 6000 City/State/Zip/Country: Binghamton, NY 13902-6000 Street Address (if different): 4400 Vestal Parkway East City/State/Zip/Country: Binghamton, NY 13902 Main Phone Number: 607-777-2000 WWW Home Page Address: www.binghamton.edu Admissions Phone Number: 607-777-2171 Admissions Toll-Free Phone Number: not applicable Admissions Office Mailing Address: P.O. -

Binghamton University Scholars Program Spring 2020 Course

Binghamton University Scholars Program Professor William Ziegler Executive Director http://binghamton.edu/scholars Spring 2020 Course Offerings TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Planning for Binghamton University Scholars Courses II. Graduating with Honors III. Priority Registration for Binghamton University Scholars IV. Spring 2020 Binghamton University Scholars Courses V. Future SCHL280/281 Course Offerings VI. Spring 2020 SCHL280/281 Courses SCHOLARS COURSE NUMBERING REMINDER: Courses previously known as the SCHL280’s now include SCHL280x and SCHL281x. All courses in those numbering rubrics meet the “SCHL280” requirements. Permission of Instructor is REQUIRED for SCHL 280D: Istanbul: Imperial City of Splendors at the Crossroads of East & West CRN 31502 **NOTE: This course includes a trip to Istanbul (additional costs apply). Please seek permission from the instructor NOW, and NO LATER THAN OCTOBER 1. Do not wait until registration opens. For permission, contact: Professor Kent Schull, [email protected]. See the SCHL280D course information in this document for full details. NOTE TO WATSON ENGINEERING MAJORS/MINORS: SCHL280B Interdisciplinary Applied Research and Proof of Concept in Aviation has been approved as an elective in some Watson programs as follows. See the SCHL280B course information in this document for details. Scholars Class Sizes are smaller than in the past, for many reasons. Smaller classes are typically considered an advantage overall, but it will also mean that the courses will fill up faster. This may mean that you will not get your first or even second choice of Scholars courses, so be sure to have contingency plans in case you do not get your preferred choices. Please do not ask to have a seat reserved in a class because the process must be fair to everyone. -

Pre-Health Freshman-Sophomore Handbook

PRE-HEALTH FRESHMAN-SOPHOMORE HANDBOOK BY W. THOMAS LANGHORNE, JR., PH.D. DIRECTOR OF PRE-HEALTH SERVICES MICHELLE D. JONES, MPA ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR-HARPUR ACADEMIC ADVISING LEAD, PRE-HEALTH ADVISING TEAM Pre-Health Advising Team-Harpur Academic Advising (for Freshmen and Sophomores) Jill Seymour Jenna Whittaker Associate Director Advisor Val Carnegie Corey Konnick Advisor Advisor Celeste Lee Kevin Curry Advisor Advisor Student Advisory Committee Dina Moumin ’18 Gabe Bedard ‘18 Danielle DiVanna ’18 Matthew Pavlica ‘18 Jenny Pak ’19 Michelle Toker ‘19 BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 FRESHMAN YEAR ....................................................................................................................... 4 Curriculum Scheduling Extra-Curricular and Related Activities Office Hours and Related Matters Student Conduct SOPHOMORE YEAR .................................................................................................................. 15 Curriculum Summer Programs Study Abroad Transitions SPECIAL PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................ 18 Harpur College Summer Physician Mentor Program Binghamton University - SUNY Optometry Joint Degree Program Binghamton University - Upstate Medical University College of Medicine Early Assurance Program Binghamton University-University at Buffalo School -

Bradley A. Goldie

Bradley A. Goldie 2022 Farmer School of Business Phone: (513) 529-3657 800 E. High Street Fax: (513) 529-6992 Miami University Email: [email protected] Oxford, OH 45056 Website: www.fsb.miamioh.edu/goldieba ACADEMIC POSITIONS Miami University, Farmer School of Business, Oxford, OH Frank H. Jellinek, Jr. Assistant Professor of Finance 2018 – Present Assistant Professor of Finance 2014 – Present University of Kansas, School of Business, Lawrence, KS Assistant Professor of Finance 2012 – 2014 EDUCATION Pennsylvania State University, Smeal College of Business, University Park, PA Ph.D., Finance 2012 Brigham Young University, Provo, UT B.S., Actuarial Science 2004 PUBLICATIONS • CFO Effort and Public Firms' Financial Information Environment, 2020, with L. Biggerstaff, D. Cicero, and L. Reid, Contemporary Accounting Research, Forthcoming. • Do Incentives Work? Option-based Incentives and Corporate Innovation, 2019, with L. Biggerstaff and B. Blank, Journal of Corporate Finance, 58, 415-430. • Does MAX Matter for Mutual Funds?, 2019, with T. Henry and H. Kassa, European Financial Management, 25 (4), 777-806. • Do Mutual Fund Investors Care About Auditor Quality?, 2018, with L. Li and A. Masli, Contemporary Accounting Research, 35 (3), 1505-1532. • What is the Nature of Hedge Fund Manager Skills? Evidence from the Risk Arbitrage Strategy, 2016, with C. Cao, B. Liang, and L. Petrasek, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 51 (3), 929-957. • Takeovers and the Size Effect, 2014, Quarterly Journal of Finance and Accounting, 52 (3&4), 53-74. Curriculum Vita – Bradley A. Goldie 1 WORKING PAPERS • Hitting the Grass Ceiling: Informal Networks and Career Outcomes for Female Executives, with L. -

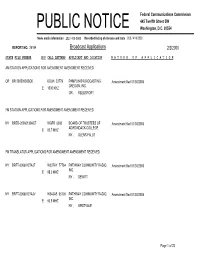

Broadcast Applications 2/2/2006

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 26164 Broadcast Applications 2/2/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT AMENDMENT RECEIVED OR BR-20050930BQE KDUN 33779 PAMPLIN BROADCASTING - Amendment filed 01/30/2006 OREGON, INC. E 1030 KHZ OR , REEDSPORT FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT AMENDMENT RECEIVED NY BRED-20060130ACT WGFR 6682 BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF Amendment filed 01/30/2006 ADIRONDACK COLLEGE E 92.7 MHZ NY , GLENS FALLS FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT AMENDMENT RECEIVED NY BRFT-20060127AJT W237AY 77734 PATHWAY COMMUNITY RADIO, Amendment filed 01/30/2006 INC. E 95.3 MHZ NY , DEWITT NY BRFT-20060127AJV W243AB 55700 PATHWAY COMMUNITY RADIO, Amendment filed 01/30/2006 INC. E 96.5 MHZ NY , WESTVALE Page 1 of 23 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 26164 Broadcast Applications 2/2/2006 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT AMENDMENT RECEIVED NY BRFT-20060127AJY W251AK 86708 PATHWAY COMMUNITY RADIO, Amendment filed 01/30/2006 INC. E 98.1 MHZ NY , NEDROW/LAFAYETTE NY BRFT-20060127AKC W268AE 87504 PATHWAY COMMUNITY RADIO, Amendment filed 01/30/2006 INC. -

Wei Jiao CONTACT INFORMATION Rutgers University Email: [email protected] Rutgers School of Business-Camden 227 Penn St, Camden, NJ 08102

Wei Jiao CONTACT INFORMATION Rutgers University Email: [email protected] Rutgers School of Business-Camden 227 Penn St, Camden, NJ 08102 EDUCATION Binghamton University – State University of New York (SUNY), Ph.D. in Finance 2018 (Winner of the University’s Distinguished Dissertation Award) Illinois Institute of Technology, M.S. in Finance 2012 Jilin University, B.S. in Finance and Statistics 2010 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Assistant Professor of Finance, Rutgers School of Business-Camden 2020–Present Assistant Professor of Finance, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay 2018–2020 Visiting Assistant Professor of Finance, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2017–2018 RESEARCH INTERESTS International Investments, Investor Behavior RESEARCH PAPERS Portfolio Manager Home-Country Culture and Mutual Fund Risk-Taking Single-authored FMA Top Papers Session 2021, Binghamton University 2017, FMA Doctoral Consortium 2016 Financial Management, Top 3 article in Fall 2020 Issue Missing Them Yet? Investment Banker Directors in the 21st Century with Murali Jagannathan and Srini Krishnamurthy Virginia Tech 2019, Kent State University 2018, Binghamton University 2017 Journal of Corporate Finance, 2020, volume 60 Is There a Home Field Advantage in Global Markets? with Murali Jagannathan and Andrew Karolyi AFA Annual Meeting 2019, Emory University 2019, Georgetown University 2019, University of Maryland 2019, University of British Columbia 2019, UMass Amherst 2019, University of Exeter 2019, University of Bristol 2019, Northern Finance Association 2018, Southern Methodist -

Binghamton University Periodic Review Report

Periodic Review Report May 20, 2016 Dr. Harvey G. Stenger President Accreditation reaffirmed March 3, 2011 Dates of Evaluation Team’s Visit November 7-10, 2010 Table of Contents Section 1 1-5 Executive Summary Section 2 6-47 Summary of Institution’s Responses to Self-Identified Recommendations from the Previous Evaluation Section 3 48-50 Narrative Identifying Major Challenges and Opportunities Section 4 51-57 Enrollment and Finance Trends and Projections Section 5 58-74 Processes to Assess Institutional Effectiveness and Student Learning Section 6 75-90 Linked Institutional Planning & Budgeting Processes Appendices Section 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Executive Summary Binghamton University Overview Founded only seventy years ago, Binghamton University has grown rapidly in size and stature, becoming one of the best mid-size public research universities in the U.S. One of four doctoral-granting University Centers in the State University of New York system, Binghamton enrolls almost 17,000 students in 74 undergraduate degrees in 261 different concentrations, 39 different masters degrees with 81 different concentrations offered by 31 different departments and programs. We enroll students in 28 different doctoral degrees, with 37 different concentrations offered by 27 different departments and doctoral programs. The University consists of seven colleges and schools, including the College of Community and Public Affairs, the Decker School of Nursing, the Graduate School of Education, the Harpur College of Arts & Sciences, the School of Management, the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (scheduled to accept its first class in August 2017), and the Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Binghamton has earned a strong reputation for excellence. -

New Mario Café Dedication 4 the Bridge Faculty Profile Fall 2018

the Fall 2018 A Magazine for SUNY Polytechnic Institute Alumni, Faculty, Friends & Students New Mario Café Dedication 4 The Bridge Faculty Profile Fall 2018 The Bridge is published by the State University of New York Polytechnic Institute Alumni Association to keep 3 you informed of campus activities and news. New Interim Provost Publisher: Andrea LaGatta Editor: David Dellecese G’18 Lynne Browne ’04, G’14 Production: Patrick Baker ’15 Matthew Kopytowski Find out more! Visit us online: www.sunypoly.edu/alumni Call: 315-792-7273 E-mail: [email protected] Address change? E-mail [email protected], 8 call 315-792-7273, or write SUNY Polytechnic Institute Alumni Office, 100 Seymour Road, New Café Dedication Utica, New York 13502. This publication is printed on recycled paper. 6 “Woman of the Year” 14 Wildcats of the Year Interim President’s Message Greetings from SUNY Poly, I am honored to write to you as SUNY Polytechnic Institute’s Interim President. In this new role, I look forward to opportunities to work with our faculty, staff, students, and you, our alumni, to move our institu- tion forward, together. I am extremely thankful to Dr. Bahgat Sammakia, who recently returned to his position at Binghamton University after leading SUNY Poly since December 2016; he provided a firm foundation for our institution to reach its full potential. Looking into the future, SUNY Poly will remain focused on enabling student success and enriching students’ lives at both of our campuses in Albany and Utica, expanding our research and innova- tion activities, and stimulating the economic growth of our community. -

1 Office: Department of Romance Languages & Literatures, PO Box 6000, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY 13902 Email

ROBYN COPE CURRICULUM VITAE Office: Department of Romance Languages & Literatures, PO Box 6000, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY 13902 Email: [email protected] Phone: (607) 777-2645 Fax: (607) 777-2644 EDUCATION 2013 Ph.D. in French, Florida State University, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, with Distinction 2003 M.Ed. in Secondary Education, Xavier University. 1994 B.A. in French, Miami University, Department of French and Italian, cum laude ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2014-present Binghamton University, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Assistant Professor of French; Affiliated Faculty, Latin American and Caribbean Area Studies (LACAS) Program; Affiliated Faculty, Sustainable Communities Transdisciplinary Area of Excellence (TAE) 2017-2020 Binghamton University, Department of Comparative Literature, Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature (courtesy title) 2013-2014 Florida State University, Graduate School, Director, Program for Instructional Excellence & Fellows Society AWARDS, FELLOWSHIPS AND HONORS 2020 Harpur College Subvention Award, The Pen and the Pan: Food, Fiction, and Homegrown Caribbean Feminism(s) monograph project. 2019 Dr. Nuala McGann Drescher Diversity and Inclusion Leave Award. 2018 Individual Development Award, “Food, Fiction, and Homegrown Caribbean Feminism(s)” conference presentation at the Global Feminisms Conference at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados. 2018 Co-recipient (with Romance Languages Pre-Tenure Faculty), Harpur College Mutual Mentoring Initiative