Disneyland, 1955: the Place That Was Also a TV Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

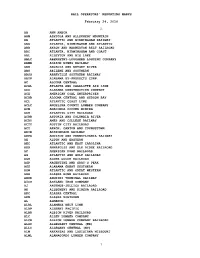

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Main Street, U.S.A. • Fantasyland• Frontierland• Adventureland• Tomorrowland• Liberty Square Fantasyland• Continued

L Guest Amenities Restrooms Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Tomorrowland® Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS AED ATTRACTIONS First Aid NEW! Presented by Florida Hospital 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad U 37 Tomorrowland Speedway 26 Enchanted Tales with Belle T AED Guest Relations Information and Lost & Found. AED 27 36 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® Be magically transported from Maurice’s cottage to E Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. ATMs 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ Beast’s library for a delightful storytelling experience. Fantasyland 26 Presented by CHASE AED 28 Package Pickup. Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. AED 27 Under the Sea~Journey of The Little Mermaid AED 34 38 Space Mountain® AAutomatedED External 35 Defibrillators ® Relive the tale of how one Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 23 S Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite ARunawayED train coaster. lucky little mermaid found true love—and legs! Designated smoking area 39 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s PhilharMagic. 21 32 Baby Care Center 33 40 Tomorrowland Transit Authority AED 28 Ariel’s Grotto Venture into a seaside grotto, Locker rentals 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island 16 PeopleMover Roll through Come explore the Island. where you’ll find Ariel amongst some of her treasures. -

HOTELS of the DISNEYLAND RESORT 165

HOLLY WIENCEK PHOTOGRAPHY by BILL SFERRAZZA and ERIC WEBER INTRODUCTION 8 DISNEYLAND PARK 10 HOTELS of the DISNEYLAND RESORT 165 DOWNTOWN DISNEY DISTRICT 171 DISNEY CALIFORNIA ADVENTURE PARK 204 DISNEYLAND RESORT IS A WORLD OF MAGIC, a place where train station and into Town Square, I was overcome with emotion. stories, fantasy and enchantment unfold. It is a playground for It was familiar, yet brand new, and possessed a vibe I could hardly the child who lives within all of us, a manifestation of one man’s explain. The Disneyland Band was playing familiar tunes, and I dream. “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, stopped in front of the fire station — Walt’s home away from home tomorrow and fantasy.” Disneyland Resort is a place where today — taking in the lamp in the window that glows as a reminder of disappears and fantasies spring to life, an imaginative story told his presence. It was surreal, as if I had just stepped into a dream, by Walt Disney that inspires all who follow in his footsteps. but I was about to walk in the same footsteps as one of the most It is no secret that I am a lifelong Disney enthusiast. It has creative minds to grace our world. been a part of my life since I was a toddler. Walt Disney World As I rounded the Emporium for my first glance of Sleeping Resort is a place where I escape my everyday world and immerse Beauty Castle, I was taken aback at how small it was. -

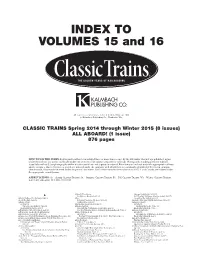

Classic Trains' 2014-2015 Index

INDEX TO VOLUMES 15 and 16 All contents of publications indexed © 2013, 2014, and 2015 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Waukesha, Wis. CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2014 through Winter 2015 (8 issues) ALL ABOARD! (1 issue) 876 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are commonly identified; if there is no common identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country name. ABBREVIATIONS: Sp = Spring Classic Trains, Su = Summer Classic Trains, Fa = Fall Classic Trains, Wi = Winter Classic Trains; AA! = All Aboard!; 14 = 2014, 15 = 2015. Albany & Northern: Strange Bedfellows, Wi14 32 A Bridgeboro Boogie, Fa15 60 21st Century Pullman, Classics Today, Su15 76 Abbey, Wallace W., obituary, Su14 9 Alco: Variety in the Valley, Sp14 68 About the BL2, Fa15 35 Catching the Sales Pitchers, Wi15 38 Amtrak’s GG1 That Might Have Been, Su15 28 Adams, Stuart: Finding FAs, Sp14 20 Anderson, Barry: Article by: Alexandria Steam Show, Fa14 36 Article by: Once Upon a Railway, Sp14 32 Algoma Central: Herding the Goats, Wi15 72 Biographical sketch, Sp14 6 Through the Wilderness on an RDC, AA! 50 Biographical sketch, Wi15 6 Adventures With SP Train 51, AA! 98 Tracks of the Black Bear, Fallen Flags Remembered, Wi14 16 Anderson, Richard J. -

Street, USA • Fantasyland• Continued Fantasyland• Frontierland

LEGE Guest Amenities Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Wishes Tomorrowland® Restrooms nighttime spectacular Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS First Aid ® See the skies of the Magic 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad 25 Mickey’s PhilharMagic 35 Tomorrowland Speedway Presented by Florida Hospital ® Kingdom light up with this Information and Lost & Found. 3D movie. Presented by Kodak . 34 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® nightly fireworks extravaganza Guest Relations Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ 26 Dream Along With Mickey that can be seen throughout ATMs Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. Presented by CHASE Package Pickup. Musical stage show. the entire Park! 32 36 Space Mountain® 23 33 Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. Automated External 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ® 27 Prince Charming Regal Carrousel See TIMES GUIDE. S Defibrillators Runaway train coaster. Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite 37 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Designated smoking area Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. 28 The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh 21 Fantasyland 30 31 Baby Care Center Roll, bounce and 38 Tomorrowland Transit Authority 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island float through indoor adventures (moments in 16 PeopleMover Roll through Locker rentals Come explore the Island. 6 Harmony Barber Shop the dark). FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s Liberty Square 24 27 Tomorrowland. -

Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom Opens Its Ticketing Gates About an Hour Before Official Park Open

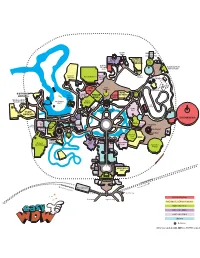

Gaston’s Tavern BARNSTORMER/ Dumbo FASTPASS Be JOURNEY OF Our Pete’s Guest QS/ TS THE LITTLE Silly MERMAID+ Sideshow Enchanted Tales with Walt Disney World Belle+ Railroad Station Ariel’s Haunted it’s a small world+ Pinocchio Mansion+ Village Grotto+ Haus BARNSTORMER+ Regal PETER Carrousel PAN+ DUMBO+ WINNIE Tea BIG THUNDER Columbia THE POOH+ MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Harbor House PRINCESS Party+ Square MAGIC+ MEET+ Walt Disney World Riverboat Railroad Station Tom Sawyer’s Hall of Pooh/ Island Presidents Mermaid FP Indy Sleepy Speedway+ Hollow Cinderella’s Cinderella Cosmic Royal Table Ray’s SPLASH Castle MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Diamond Tree SPACE MOUNTAIN+ H’Shoe Shooting Pecos Country Stitch Auntie Bill Arcade Astro Orbiter Golden Bears Gravity’s Oak Outpost Aloha Isle Tortuga Lunching Pad Tavern Tiki Room Swiss PeopleMover Aladdin’s Family Dessert Monsters Inc. Carpets+ Treehouse Party Laugh Floor+ BUZZ+ JUNGLE Crystal Casey’s Plaza Tomorrowland Pirates of CRUISE+ Palace Corner the Caribbean+ Rest. Terrace Carousel of Main St Progress Bakery SOTMK Tony’s Town Square City Hall MICKEY MOUSE MEET+ Railroad Station t ary Resor emopor Fr ont om Gr Monorail Station To C and Floridian Resor t Resort Bus Stop First Hour Attractions Boat Launch Ferryboat Landing First 2 Hours / Last 2 Hours of Operation Anytime Attractions Table Service Dining Quick Service Dining Shopping Restrooms Attractions labelled in ALL CAPS are FASTPASS enabled. Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom opens its ticketing gates about an hour before official Park open. Guests are held just inside the entrance in the courtyard in front of the train station. The opening show, which features Mickey and the gang arriving via steam train, begins 10 to 15 minutes prior to Park open and lasts about seven minutes. -

Street, Usa New Orleans Square

L MAIN STREET, U.S.A. FRONTIERLAND DISNEY DINING MICKEY’S TOONTOWN FANTASYLAND Restrooms 28 The Golden Horseshoe Companion Restroom ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS Chicken, fish, mozzarella strips, chili and ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS Automated External 1 Disneyland® Railroad 22 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 44 Chip ’n Dale Treehouse 53 Alice in Wonderland tasty ice cream specialties. Defibrillators 2 Main Street Cinema 29 Stage Door Café 45 Disneyland® Railroad 54 Bibbidi Bobbidi Boutique 55 Casey Jr. Circus Train E Information Center Main Street Vehicles* (minimum height 40"/102 cm) Chicken, fish and mozzarella strips. 46 Donald’s Boat Guest Relations presented by National Car Rental. 23 Pirate’s Lair on 30 Rancho del Zocalo Restaurante 47 Gadget’s Go Coaster 56 Dumbo the Flying Elephant (One-way transportation only) 57 Disney Princess Fantasy Faire Tom Sawyer Island* hosted by La Victoria. presented by Sparkle. First Aid (minimum height 35"/89 cm; 3 Fire Engine 24 Frontierland Shootin’ Exposition Mexican favorites and Costeña Grill specialties, 58 “it’s a small world” expectant mothers should not ride) ATM Locations 4 Horse-Drawn Streetcars 25 Mark Twain Riverboat* soft drinks and desserts. 50 52 presented by Sylvania. 49 48 Goofy’s Playhouse 5 Horseless Carriage 26 Sailing Ship Columbia* 31 River Belle Terrace 44 59 King Arthur Carrousel Pay Phones 49 Mickey’s House and Meet Mickey 60 Mad Tea Party 6 Omnibus (Operates weekends and select seasons only) Entrée salads and carved-to-order sandwiches. 48 51 47 50 Minnie’s House 61 Matterhorn Bobsleds Pay Phones with TTY 27 Big Thunder Ranch* 32 Big Thunder Ranch Barbecue 46 7 The Disney Gallery 51 Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin (minimum height 35"/89 cm) hosted by Brawny. -

Magic Kingdom

Mickey’s PhilharMagic Magic Kingdom 2 “it’s a small world” 8 ® 23 attractions ® 9 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic – 1 0 Dumbo the Flying Elephant® – 5 Join Donald on a musical 3-D Soar over Fantasyland. 4 6 7 movie adventure through Disney classics. Theater does 1 1 The Barnstormer® – become dark at times with Take to the sky with the occasional water spurts. Flying Goofini. 1 2 Buzz Lightyear’s Space 10 3 11 ® 2 “it’s a small world” – Sail off Ranger Spin – Zap aliens and fantasyland on a classic voyage around the save the galaxy. world. Inspired by Disney•Pixar’s “Toy Story 2.” 3 Peter Pan’s Flight – Take a 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic fl ight on a pirate ship. 1 3 Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor – An ever-changing, 4 Cinderella’s Golden interactive giggle fest starring BIG THUNDER Carrousel – Take a magical Mike Wazowski. Inspired by MOUNTAIN RAILROAD Dumbo ride on an enchanted horse. Disney·Pixar’s “Monsters, Inc.” the Flying 24 5 Dumbo the Flying Elephant – 14 Walt Disney World® Railroad Elephant Soar the skies with Dumbo. – Hop a steam train that makes stops at Frontierland, 6 The Many Adventures of Mickey’s Toontown TOMORROWLAND Fair and frontierland® Winnie the Pooh – Visit the Main Street, U.S.A. INDY SPEEDWAY Hundred Acre Wood. 1 5 The Magic Carpets of 16 7 Mad Tea Party Aladdin tomorrowland® – Go for – Fly high over 19 a spin in a giant teacup. the skies of Agrabah. 20 8 Pooh’s Playful Spot – 1 6 Country Bear Jamboree – 18 Dream-Along With 21 Outdoor play break area. -

The 50Th Magical Milestones Penny Machine Locations

Magical Milestones Penny Press Locations Magical Milestones Penny Press Locations This set has been retired and taken off-stage This set has been retired and taken off-stage Magical Milestones Pressed Penny Machine Locations List Magical Milestones Pressed Penny Machine Locations List Disneyland's 50th Anniversary Penny Set Disneyland's 50th Anniversary Penny Set Courtesy of ParkPennies.com ©2006 Courtesy of ParkPennies.com ©2006 Updated 10/2/06 Sorted by Magical Milestones Year Sorted by Machine Location YEAR Magical Milestones Theme 50th Penny Machine Location 1962 Swiss Family Tree House opens (1962) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1955 Opening Day of Disneyland ® park (July 17, 1955) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 2 1994 "The Lion King Celebration Parade" debuts (1994) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1956 Tom Sawyer Island opens (1956) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1999 Tarzan's Treehouse™ opens (1999) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1957 House of the Future opens (1957) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 5 1956 Tom Sawyer Island opens (1956) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1958 Alice In Wonderland opens (1958) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 6 1963 Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room opens (1963) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1959 Disneyland® Monorail opens (1959) Disneyland Hotel - Fantasia Gift 1995 Indiana Jones Adventure™ - Temple of the Forbidden Eye open (1995) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1960 Parade of Toys debuts (1960) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 4 1965 Tencennial Celebration (1965) Disneyland Hotel - Fantasia Gift Shop The Disneyland® Hotel is purchased by The Walt Disney Co. -

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(S): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed Work(S): Source: American Art, Vol

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(s): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed work(s): Source: American Art, Vol. 5, No. 1/2 (Winter - Spring, 1991), pp. 168-207 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109036 . Accessed: 06/12/2011 16:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Art. http://www.jstor.org Disneyland,1955 Just Takethe SantaAna Freewayto theAmerican Dream KaralAnn Marling The opening-or openings-of the new of the outsideworld. Some of the extra amusementpark in SouthernCalifornia "invitees"flashed counterfeit passes. did not go well. On 13 July, a Wednes- Othershad simplyclimbed the fence, day, the day of a privatethirtieth anniver- slippinginto the parkin behind-the-scene saryparty for Walt and Lil, Mrs. Disney spotswhere dense vegetation formed the herselfwas discoveredsweeping the deck backgroundfor a boat ride througha of the steamboatMark Twainas the first make-believeAmazon jungle. guestsarrived for a twilightshakedown Afterwards,they calledit "Black cruise.On Thursdayand Friday,during Sunday."Anything that could go wrong galapreopening tributes to Disney film did. -

1949 Chicago Railroad Fair Official Guide Book Wheels A-Rolling

2nd GREAT YEAR The Chicago Railroad Fair IS PRESENTED BY The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway System Illinois Central Railroad The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company Lake Superior & Ishpeming Railroad Company The Boston and Maine Railroad Maine Central Railroad Company Durlington Lines Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company The Monongahela Railway Company Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad New York Central System Chicago Great Western Railway Nickel Plate Road- The New York, Chicago and St. Louis Chicago & Illinois 1idland Railway Company Railroad Company Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway Company- Norfolk Southern Railway Company Monon Northern Pacific Railway Company Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad Pennsylvania Railroad Company The Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railway Company Chicago And Nnrth Western Railway System The Pullman Company The Colorado & Wyoming Railway Company Rock Island Lines- Ch icago, Rock Island and Pacific Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad Railroad Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railway Company Soo Line-Minneapolis, St. Paul & Saulte Ste. Marie Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway Company Railroad Erie Railroad Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway Company Grand Trunk Railway ystem The Texas-Mexican Railway Company Great Northern Railway Company Union Pacific Railroad Green Bay & Western Lines Wabash Railroad Company Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad- The Alton Route Western Pacific Railroad Company OFFICERS President LENOX R. LOHR President, Museum of Science and Industry Vice-President Treasurer Secretary R. L. WILL IAMS WAYNE A_ JOH STON G. M. CAMPBELL President, Chicago And President, Illinois Vice-Pres. and Exec. Rep. North Western Railway System Central Railroad The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company DIRECTORS ARTHUR K.