The Woman Behind It All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nyhetsbrev För Kommunbygderådets Tre Projekt, Landsbygds-TV

Gemensamt nyhetsbrev för kommunbygderådets tre projekt, Landsbygds-TV RonnebySlingor, Arbetsmarknadsprojektet Attraktiv Ronneby Landsbygd RonnebySlingor vid halvtid med Sven Strandberg, Hallabro och Blomstrande Bygden. Dessutom är ordföranden vid Ronneby Inget är som vanligt. Men projektet RonnebySlingor fortgår enligt plan och vi har nu kommunbygderåd, Helena Carlberg Andersson, ofta avverkat första halvleken och har just kickat igång adjungerad. den andra Till projektet är det också knutet ett arbetslag, där arbetskostnaderna finansieras via ett Den här våren svepte en pandemi in över oss och projektet. Med den följde svårigheter att jobba som vi Arbetsmarknadsprojekt i samverkan mellan Ronneby kommun och Bygd i Samverkan medan gjort förut. Pandemin orsakade stora konsekvenser för människors hälsa och ekonomi världen över. Projektet materialkostnaden fås via RonnebySlingors egna RonnebySlingor är inte förskonat. budget. Men vi har inte suttit och deppat utan jobbat på och Ny landsbygdsutvecklare letat nya lösningar för att komma framåt. Ebon Kajsajuntti slutade som landsbygdsutvecklare Projektet RonnebySlingor har fått än större betydelse 2020-06-30. för framtiden i dessa tider inte minst när vi talar ”hemster” som ett nytt begrepp. Ny landsbygdsutvecklare är Daniel Granello. Han jobbade tidigare som landsbygdsutvecklare i Region Vi vill därför berätta var vi står med projektet efter en Kalmar, bor i Karlskrona och började sitt arbete i halvlek och vad som är på gång i andra halvleken. Ronneby den 21september. Projektet finansieras av Ronneby Kommun och Sydost Leader Projektet är tvåårigt och statades oktober 2019. Det genomförs i samverkan mellan Ronneby kommun och Ronneby kommunbygderåd. Fram tills nu har projektet leds av Ronneby kommun med Ebon Kaisajuntti*som landsbygdsutvecklare och projektansvarig samt med Ola Johansson som operativ projektledare. -

Ronneby Kommun

Ronneby 2018 Tätortsbeteckning 1. Backaryd 2. Bräkne-Hoby 3. Eringsboda 4. Hallabro 5. Johannishus 6. Kallinge 7. Kuggeboda 8. Listerby 9. Ronneby 10. Ronnebyhamn 11. Saxemara 12. Utanför tätort • Tätort, minst 200 inv. Källa: Registret över totalbefolkningen (RTB), SCB Folkmängd och landareal Tätort Folkmängd Areal, km2 Täthet Avstånd 2015 till 2017 2010 Förändring 2015 inv/km2 centrum Backaryd 400 365 35 0,71 545 17,2 Bräkne-Hoby 1 718 1 713 5 2,41 709 10,3 Eringsboda 293 304 -11 0,78 354 26,3 Hallabro 274 258 16 0,61 426 23,1 Johannishus 768 748 20 1,00 768 8,6 Kallinge 4 871 4 587 284 5,54 842 4,6 Kuggeboda 451 472 -21 2,41 186 8,6 Listerby 987 971 16 2,10 461 7,1 Ronneby 13 076 12 077 999 8,21 1 537 Ronnebyhamn 751 725 26 1,97 381 3,3 Saxemara 432 418 14 2,10 204 5,9 Utanför tätort 5 547 5 616 -69 Not: Alla uppgifter i tabeller/diagram redovisas enligt SCB:s tätortsavgränsning 2015. Avgränsningen 2015 är framtagen enligt en ny modell vilket innebär att jämförelser inte kan göras med tidigare år. Se vidare under Tätort i definitionerna för Baspaketet. I tabellen ovan är 2010 års befolkningsuppgifter framtagna enligt tätortsavgränsningen 2015. Källa: Registret över totalbefolkningen (RTB), SCB SCB 2018 Ronneby Folkmängd efter tätort och år 400 Backaryd 365 1 718 Bräkne-Hoby 1 713 293 Eringsboda 304 274 Hallabro 258 768 Johannishus 748 4 871 Kallinge 4 587 451 Kuggeboda 472 987 Listerby 971 13 076 Ronneby 12 077 751 Ronnebyhamn 725 432 Saxemara 418 5 547 Utanför tätort 5 616 År 2017 2010 Befolkningen efter kön och ålder 2017 Tätort -

Besöksguide 2018

Besöksguide 2018 Officiell Turistguide Official Tourist Guide Offizieller Touristenguide Oficjalny przewodnik turystyczny Lars Winnerbäck 8 juli 30 juni Nostalgia Festival 29 juni - 8 juli Ronneby Brunnspark Schack-SM BCC, Ronneby Brunn 5 juli Familjefesten 6 - 8 juli Musik, Brunnsparken Tosia Bonnada’n Marknad, centrum 20 - 26 augusti SM i Brukshund 5 - 9 september Ronneby Brunnspark VM i Casting Ronneby Brunnspark SILLARODDEN CRUISING SOMMARTEATER RUNNEBY 16 juni 29 juni 13 juni - 4 augusti 1 september Se fler evenemang på visitronneby.se 4 Sommarens GUIDADE TURER Onsdagar Dagligen Söndagar 27 juni - 8 augusti 22 juni - 12 augusti 8 - 29 juli Stadsvandringar Guidad skärgårdstur Spökvandring Ronneby stadskärna Ronnebyån, skärgården Karön Under sommaren väcks I sommar finns det Känn pulsen öka på historiska karaktärer till möjlighet att lyssna på sommarens läskiga liv under dramatiserade en guidning om platserna spökvandringar ute på vandringar. skärgårdsbåten åker förbi. semesterpärlan Karön. Ronnebys guidningsapp Ladda ner appen Nyfiken på Ronnebys sevärdheter? Nu kan du gå guidade turer i vackra Ronneby Brunnspark och i kulturkvarteren Bergslagen. Google Play och App Store Mer information www.visitronneby.se 3 Äta och bo SID 22 Stanna till och njut SID 8 Ronneby Brunnspark SID 16 Ett pärlband av kulturSID 28 5 Luffa runt bland öarna 25 Tosia Bonnada'n Island hopping in Ronneby/ Inselhüpfen in Ronneby / W rejs z Ronneby 28 Ett pärlband av kultur 8 Cultural delights/ Kulturelle Höhepunkte/ Stanna till och njut Kultura na wyciągnięcie -

FÖRSKÖNING Medel Till Förskönande Genom Nya Objekt, Förbättringar Och Underhåll På Landsbygden I Ronneby Kommun

FÖRSKÖNING Medel till förskönande genom nya objekt, förbättringar och underhåll på landsbygden i Ronneby kommun Så här har försköningspengarna använts hittills INNEHÅLL Del 1. Försköningspengarna - Allmän del 6. Historiken FÖRSKÖNINGSPENGARNA 7. Hur har det blivit? 8. Några exempel på större, mer samlade satsningar 14. Målbilder - grundläggande principer och typer av objekt 23. Om bygdekänslan, platserna, de sammanhängande stråken Allmän del 30. I verkstan, om tillverkningen och uppväxlingen 37. Några sammanfattande kommentarer 38. Delar som bör kunna förbättras framöver Del 2. Försköningspengarna - Exempelsamling från samhälle till samhälle 44. Backaryd 46. Belganet 48. Blekingepärlor 50. Bräknebygden Bräkne-Hoby med omland 52. Bräknebygden Järnaviksskärgården 54. Eringsboda 56. Hallabro 58. Johannishus 60. Kuggebodalandet 62. Listerby 64. Möljeryd - Karlsnäs 66. Saxemara 68. Tjurkhult 70. Öljehult Skriften FÖRSKÖNING är utgiven av Försköningsrådet i Ronneby kommun och Ronneby Kommunbygderåd. Ansvarig för innehållet i den Allmänna delen och för flera delar även gällande Exempelsamlingen är Roland Gustavsson. Layout och originalproduktion Ingegerd Linden. Tryck Copy Graf, Bräkne-Hoby. Många har bidragit med foton. För andra delen ombads samhällsföreningar mm att komma in med bilder som sammanfattade arbetet med försköningsmedlen för deras by. För att understryka det viktiga tillverkandet så ville vi få exempel på själva arbetet som del. Vi ville även få bilder över hela året då vi vill stimulera att användandet inte bara sker över en kort sommarperiod utan mest möjligt över hela året! Utanför dessa så har det största antalet foton, mer än åttio, ta- gits av Roland Gustavsson. Andra som bidragit är Bo Svensson, Saxemara, Ola Johansson, Eringsboda, Sven Strandberg, Hallabro, Stefan Rehberg, Bräkne- Hoby, Maria Dehlsen, Belganet samt Ingegerd Linden, Bräkne-Hoby. -

SCB Statistik Kommunfakta 2019

Ronneby 2019 Tätortsbeteckning 1. Backaryd 2. Bräkne-Hoby 3. Eringsboda 4. Hallabro 5. Johannishus 6. Kallinge 7. Kuggeboda 8. Listerby 9. Ronneby 10. Ronnebyhamn 11. Saxemara 12. Utanför tätort • Tätort, minst 200 inv. Källa: Registret över totalbefolkningen (RTB), SCB Folkmängd och landareal Tätort Folkmängd Areal, km2 Täthet Avstånd 2015 till 2018 2010 Förändring 2015 inv/km2 centrum Backaryd 397 365 32 0,71 545 17,2 Bräkne-Hoby 1 719 1 713 6 2,41 709 10,3 Eringsboda 283 304 -21 0,78 354 26,3 Hallabro 269 258 11 0,61 426 23,1 Johannishus 756 748 8 1,00 768 8,6 Kallinge 4 938 4 587 351 5,54 842 4,6 Kuggeboda 443 472 -29 2,41 186 8,6 Listerby 1 003 971 32 2,10 461 7,1 Ronneby 13 056 12 077 979 8,21 1 537 Ronnebyhamn 746 725 21 1,97 381 3,3 Saxemara 458 418 40 2,10 204 5,9 Utanför tätort 5 627 5 616 11 Not: Alla uppgifter i tabeller/diagram redovisas enligt SCB:s tätortsavgränsning 2015. Avgränsningen 2015 är framtagen enligt en ny modell vilket innebär att jämförelser inte kan göras med tidigare år. Se vidare under Tätort i definitionerna för Baspaketet. I tabellen ovan är 2010 års befolkningsuppgifter framtagna enligt tätortsavgränsningen 2015. Källa: Registret över totalbefolkningen (RTB), SCB SCB 2019 Ronneby Folkmängd efter tätort och år 397 Backaryd 365 1 719 Bräkne-Hoby 1 713 283 Eringsboda 304 269 Hallabro 258 756 Johannishus 748 4 938 Kallinge 4 587 443 Kuggeboda 472 1 003 Listerby 971 13 056 Ronneby 12 077 746 Ronnebyhamn 725 458 Saxemara 418 5 627 Utanför tätort 5 616 År 2018 2010 Befolkningen efter kön och ålder 2018 Tätort -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

Elfiske I Ronneby Kommun 1987-2006

2006:18 ElfiskeUtvärdering av fiskfaunan i Ronneby i vattendrag inom Ronnebykommun kommun 1987-2006 Rapport, år och nr: 2006:18 Rapportnamn: Elfisken i Ronneby kommun 1987 - 2006 Utgivare: Länsstyrelsen Blekinge län, 371 86 Karlskrona. Hemsida: www.k.lst.se (kan hämtas/beställas via hemsidan) Dnr: 581-9080-2006 Författare: Ulf Bjelke Kontaktpersoner: Ulf Bjelke, Lars Möller Omslagsbild: Bräkneån vid Örseryd Foto: Ulf Bjelke ISSN: 1651–8527 © Länsstyrelsen Blekinge län Elfiske i Ronneby kommun 1987 - 2006 Förord/sammanfattning Rapporten är en sammanställning av elfisken i Ronneby kommun. Den visar både positiva och mindre bra förhållanden vad gäller fiskfaunan. Åarna som undersökts (Listerbyån, Angelskogsån, Heabybäcken, Ronnebyån, Vierydsån och Bräkneån) hyser i de flesta fall goda tätheter av havsöring i de nedersta delarna. Flera fiskvägar har byggts under perioden och dessa har haft en positiv effekt och ökat utbredningen av havsvandrande fisk. De högsta tätheterna finns dock i de små vattendragen Heabybäcken och Sörbybäcken. Det sistnämnda är ett biflöde till Ronnebyån. En bit upp i åarna är tätheterna av öring dock betydligt lägre eller nästintill obefintliga. Detta beror på vandringshinder och mindre bra bottenförhållanden. På de ställen där stationär öring finns är bestånden vanligen lägre än vad som är normalt för södra Sverige enligt Fiskeriverkets statistik över elfisken. Goda bestånd av öring är något att eftersträva då sådana miljöer oftast hyser en mångfald även av andra arter. Måttliga insatser i form av biotopvård och anläggande av fiskvägar skulle sannolikt kunna ge stora vinster i form av ökade naturvärden men även av förbättrat fiske i kustområdet. Särskilt gäller detta i de minsta bäckarna som ofta försummas i fiske- och naturvårdssammanhang. -

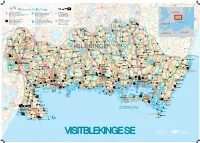

Visit Blekinge Karta

Påryd 126 Rävemåla 28 Törn Flaken Welcome to Blekinge 120 ARK56 Nav - Ledknutpunkt ARK56 Kajakled Blekingeleden Häradsbäck 120 Markerad vandringsled Sandsjön SWEDEN ARK56 Hub - Trail intersection120 Rekommenderad led för paddling Urshult Tingsryd Kvesen Vissefjärda ARK56 Knotenpunkt diverser Wege und Routen Recommended trail for kayaking Waymarked hiking trail ARK56 Węzeł - punkt zbiegu szlaków Empfohlener Paddel - Pfad Markierter Wanderweg 122 www.ark56.se Zalecana trasa kajakowa Oznakowany szlak pieszy Tiken 27 Dångebo Campingplatser - Camping Sydost RammsjönSkärgårdstrafik finns i området Sydostleden Arasjön Campsites - Camping Sydost Passenger boat services available Rekommenderad cykelled Stora Kinnen Halltorp Campingplatz - Camping Sydost Skärgårdstrafik - Passagierschiffsverkehr Recommended cycle trail Hensjön Ulvsmåla Älmtamåla Kemping - Camping Sydost Obszar publicznego transportu wodnego Empfohlener Radweg Baltic Sea www.campingsydost.se www.skargardstrafiken.com Zalecany szlak rowerowy 119 Ryd Djuramåla Saleboda DENMARKGullabo Buskahult Skumpamåla Spetsamåla Söderåkra Lyckebyån Siggamåla Åbyholm Farabol 119 Eringsboda Alvarsmåla Tjurkhult Göljahult Kolshult Falsehult POLAND130 126 GERMANY Mien Öljehult Husgöl Torsåsån Värmanshult Hjorthålan Holmsjö Fridafors R o Leryd Sillhöv- Kåraboda Björkebråten n Ledja n Boasjö 27 e dingen Torsås b y Skälmershult Björkefall å n Ärkilsmåla Dalanshult Hallabro Brännare- Belganet Hjortseryd Långsjöryd Klåvben St.Skälen Gnetteryd bygden Väghult Ebbamåla Alljungen Brunsmo Bruk St.Alljungen Mörrumsån -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook to the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

Clubadmin Rotary Sverige Medlemsdata

Rotary Sverige ClubAdmin Medlemsdata - Klubb 13255 RONNEBY Nuvarande registeruppgifter Plats for korrigering/komplettering Namn: Albertsson, Heine Titel: VD Adress: Vännershall Postnr/ort: 37012 / Hallabro Född: 1932-07-02 Kön: M In i Rotary: 2012 I denna Klubb: Kategori: Active Klassifikation: Building Equipment Management Tidigare: Klubbar: Uppdrag: Arbetsplats: Rebecco Trading AB, Box 164, 37012 H Partner: Ulla Albertsson E-Post: [email protected] Mobil: 070-3751200 Skapad Sida 1 av 45 Rotary Sverige ClubAdmin Medlemsdata - Klubb 13255 RONNEBY Nuvarande registeruppgifter Plats for korrigering/komplettering Namn: Andersson, Laila Titel: Rektor Adress: Kungsgatan 51 Postnr/ort: 37237 / Ronneby Född: 1938-04-05 Kön: F In i Rotary: 2012 I denna Klubb: Kategori: Active Klassifikation: Grade school adm Tidigare: Klubbar: Uppdrag: Arbetsplats: Pensionär Partner: E-Post: [email protected] Mobil: 0733-854542 Skapad Sida 2 av 45 Rotary Sverige ClubAdmin Medlemsdata - Klubb 13255 RONNEBY Nuvarande registeruppgifter Plats for korrigering/komplettering Namn: Arnesjö, Bo Titel: Professor emeritus, Adress: Nedre Brunnsvägen 20 Postnr/ort: 37236 / Ronneby Född: 1934-03-21 Kön: M In i Rotary: 1975 I denna Klubb: Kategori: Active Klassifikation: Diagnosis Related Groups Tidigare: Klubbar: Uppdrag: Arbetsplats: Pensionerad från BTH och Univers. i Bergen Partner: Bodil Arnesjö E-Post: [email protected] Mobil: 0733-618588 Skapad Sida 3 av 45 Rotary Sverige ClubAdmin Medlemsdata - Klubb 13255 RONNEBY Nuvarande registeruppgifter Plats -

Häng Med När PRO Blekinge Startar Upp!

Häng med när PRO Blekinge startar upp! PRO Blekinge - Årsmöte 12 augusti kl. 09.30 PRO Lyckeby - Friluftsdag 22 september kl. 11.00-15.00 Nakterhuset, Sölvesborg. Årsmötet beräknas vara klart vid 13-tiden och PRO Mariagården, Lyckeby. Friluftsdag med tipspromenad och tävlingar. Blekinge inbjuder därefter till kulturarrangemang vid Sölvesborgs idrottsplats, Föreningen bjuder på grillkorv och kaffe. Egen dricka medtages. Svarta led kl.14.00-16.00. Här bjuder distriktet på tipsrunda, grillad korv, OBS! Ingen anmälan krävs. Kontakt: [email protected] kaffe och kaka, musikunderhållning av Stefan Nilsson, Nogersund. Alla är hjärtligt välkomna till en givande och trevlig eftermiddag. PRO Mjällby - Månadsmöte 27 augusti kl. 14.00 Nogersunds Bygdegård. Höstens första månadsmöte med PRO Asarum- Årsmöte 26 augusti kl. 14.00 information och underhållning. Vi bjuder på kaffe med dopp. Svängsta Medborgarhus. Årsmöte med årsmötesförhandlingar, Anmälan sker till respektive kontaktombud. parentation, fika och underhållning. Kontakt: Diez Nobach, 0708 323 139, [email protected] PRO Mörrum-Elleholm - Medlemsmöte 7 september kl. 14.00-17.00 PRO Aspö - Tipspromenad 25 augusti kl. 12.15 Mörrum Folkets Hus. Medlemsmöte med underhållning av BG & JB. PRO Gården. Vi bjuder på korv med bröd och fika. Kontakt: Gun Fernström, 0708 921 993 Ingen föranmälan krävs. Kontakt: Ann-Sofi Ingwall, 0731 408 913, [email protected] PRO Norje - Årsmöte 18 augusti kl. 13.30-16.30 PRO Bräkne-Hoby - Tipspromenad 18 augusti kl. 14.00 Norje Hembygdsgård. Årsmöte utomhus med underhållning av PRO lokalen i Bräkne-Hoby. Upptaktsmöte med tipsrunda, korv och kaffe. Elvis4Ever och förtäring. Kontakt: Kontakt: [email protected] Kenneth Colliander, [email protected] PRO Fridlevstad - Årsmöte 18 augusti kl. -

Blekinge Utflyktsguide

Blekinge BLEKINGEUTFLYKTSGUIDEUtfl yktsguide Vår webbplats har större kartor och mer information www.lansstyrelsen.se/blekinge Välkommen till våra fi naste naturområden Utflyktsguiden är utgiven av Länsstyrelsen Blekinge län 2018. 371 86 Karlskrona, tel 010-224 00 00 Grafi skformgivning och produktion: Hans Andersson, Andersson Grafi sk Form AB Kartor: Kenneth Kaisajuntti. Kartprojekt AB Fotograf: Robert Ekholm (där inget annat anges) Övriga fotografer: Hans Andersson: sid 2, 16, 17mh, 24n, 37n, 96m. Lotta Bergström: sid 27, 95öh. Bergslagsbild: sid 40n, 45n, 51ö, 80, 89mh, 97. Blekinge museum: 2 st sid 48. Markus Forslund: sid 17n, 17öv, 18öv, 23nh, 25h, 36ö, 38mh, 39, 53h, 55n, 57ö, 74n, 79öv, 82, 83m, 90, 92nv. Anders Johansson: sid 26ö, 31m, 69ö, 94ö, 95mv. Åke Nilsson: sid 40öv, 41nh. Nils-Gustaf Nydolf: sid 85h, 95nh. Tryck: Elanders Sverige AB. Papper: MultiArt silk. Upplaga: 20˛000 ex. Kartor: © Länsstyrelsen Blekinge län © Lantmäteriet Geodatasamverkan (samtliga bakgrundskartor) Utflyktsguiden finns att hämta, i pdf-format, på www.lansstyrelsen.se/blekinge Tryckta exemplar kan beställas från länsstyrelsen. Blekinge har naturområden som är helt unika. Vår lövskogskust och skärgård saknar mot- svarighet i landet. Denna naturguide är avsedd att hjälpa dig att hitta dessa välkända och okända pärlor. Det fi nns något för alla, såväl erfarna friluftsmänniskor som barnfamiljer. Du hittar vildmarksartade naturskogar, blomstrande slåtterängar och lummiga ekhagar. Här fi nns 43 av de mest besöksvärda områdena i Blekinge. Det är bara att ta sig ut och sedan njuta. Sten Nordin Landshövding i Blekinge län 3 ÖSTER SJÖN • 1–43 Blekinges fi naste naturområden 4 • 44–111 övriga naturreservat se sid 92-93 ÖSTER SJÖN 5 Innehåll Teckenförklaring industri 0 0 0 25 Bl led 0 75 100 0 Fält 11 0 63 0 åker 5 17 69 0 löv utanför reservat 14 0 30 0 häll 14 0 0 43 hav 33 9 0 0 löv 32 0 57 0 gran 46 0 72 0 led grön 87 36 100 30 , stad 41 70 56 Avfart E22 HÖKD 38 67 33 6 Beskrivna områden Innehåll Förord .....................................................sid 3 24.