Walkerton Format Guide 1011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2014-16

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2014-16 PDF version Route reference: 2013-335 Ottawa, 22 January 2014 Dufferin Communications Inc. Meaford, Ontario Application 2012-0994-0, received 16 August 2013 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 12 September 2013 English-language FM radio station in Meaford The Commission approves an application for a broadcasting licence to operate an English-language commercial FM radio station in Meaford, Ontario. The application 1. Dufferin Communications Inc. (Dufferin) filed an application to operate an English-language commercial FM radio station in Meaford, Ontario. The station would operate at 99.3 MHz (channel 257A) with an average effective radiated power of 100 watts (non-directional antenna with an effective height of antenna above average terrain of 177 metres). 2. Dufferin is a wholly owned subsidiary of Evanov Communications Inc., a corporation controlled by Mr. William Evanov. 3. The proposed station would offer an Adult Contemporary/Easy Listening music format. The station would broadcast 126 hours of local programming each broadcast week, including 18 hours of spoken word programming, 6 hours and 15 minutes of which would consist of pure news. Spoken word programming would include news, weather, sports and a number of specialty spoken word segments relating to its audience, such as Community Calendar, Big Apple Bites (agricultural reports), An Apple a Day (health watch features) and Apple Seedlings (a feature on Canadian emerging artists). 4. Dufferin committed to exceed the minimum contribution to Canadian content development (CCD) required by section 15 of the Radio Regulations, 1986 (the Regulations). Specifically, it committed to devote, by condition of licence, over and above the basic annual contribution to CCD, a total of $32,000 to CCD over seven consecutive broadcast years upon commencement of operations. -

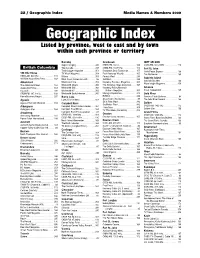

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Community Profile

Community Profile TOWNSHIP OF HURON-KINLOSS, ONTARIO APM-REP-06144-0119 NOVEMBER 2014 This report has been prepared under contract to the NWMO. The report has been reviewed by the NWMO, but the views and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NWMO. All copyright and intellectual property rights belong to the NWMO. For more information, please contact: Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East, Sixth Floor Toronto, Ontario M4T 2S3 Canada Tel 416.934.9814 Toll Free 1.866.249.6966 Email [email protected] www.nwmo.ca Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) Community Profile: Huron-Kinloss Environment Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) Community Profile: Huron-Kinloss Prepared by: AECOM 105 Commerce Valley Drive West, Floor 7 905 886 7022 tel Markham, ON, Canada L3T 7W3 905 886 9494 fax www.aecom.com Project Number: 60300337 Date: November, 2014 Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) Community Profile: Huron-Kinloss Statement of Qualifications and Limitations The attached Report (the “Report”) has been prepared by AECOM Canada Ltd. (“Consultant”) for the benefit of the client (“Client”) in accordance with the agreement between Consultant and Client, including the scope of work detailed therein (the “Agreement”). The information, data, recommendations and conclusions contained in the Report (collectively, the “Information”): is subject to the scope, schedule, and other constraints and limitations in the Agreement and the qualifications contained in the Report -

2011 Radio PSA Nat'l Stn List.R3 Copy

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION April 2012 Ontario-Only (Eng Fre) Staon Vernacular Lang Type Format City Prov Owner,Firm Phone Number CHLK-FM Lake 88.1 E FM Music; News; Pop Music Perth ONT (Perkin) Brian & Norm Wright +1 (613) 264-8811 CFWC-FM E FM Music; News; ChrisPan Music BranQord ONT 1486781 ONT Limited +1 (519) 759-2339 CKAV-FM Aboriginal Voices Radio E FM Music; News Toronto ONT Aboriginal Voices Radio Inc. +1 (416) 703-1287 CJRN-AM CJRN E AM Music; News Niagara Falls ONT AM 710 Radio Inc. (905) 356.6710 Ext.231 CJAI-FM Amherst Island Public Radio E FM Music; News Stella ONT Amherst Island Public Radio +1 (613) 384-8282 CHAM-AM 820 CHAM E AM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Music; News; Sports Hamilton ONT Astral Media +1 (905) 574-1150 Ext. 421 CKLH-FM 102.9 K-Lite FM E FM Music; News CKOC-AM Oldies 1150 AM Music; News; Oldies CIQM-FM 97-5 London's EZ Rock E FM Music; News; Pop Music CJBK-AM News Talk 1290 CJBK E AM News; Sports London ONT Astral Media +1 (519) 686-6397 CKSL-AM Funny 1410 E AM Music; News; Oldies CJBX-FM News Talk 1290 CJBK E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; London ONT Astral Media +1 (519) 691-2403 Music; News CJOT-FM Boom 99.7 E FM Music; News; Rock Music Oawa ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 225-1069 Ext. 271 CKQB-FM 106-9 The Bear E FM Music; News; Rock Music Oawa ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 225-1069 CHVR-FM Star 96 E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Pembroke ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 735-9670 Ext. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-472

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-472 Ottawa, 28 September 2005 Blackburn Radio Inc. Wingham, Ontario Application 2004-1568-9 Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2005-56 7 June 2005 CIBU-FM Wingham – Technical change The Commission approves the application by Blackburn Radio Inc. to change the authorized contours of its radio station CIBU-FM Wingham. The application 1. The Commission received an application by Blackburn Radio Inc. (Blackburn) proposing to change the authorized contours of the radio programming undertaking CIBU-FM Wingham by increasing the average effective radiated power from 21,200 watts to 70,140 watts and by decreasing the antenna height. 2. Blackburn’s original application for a licence to operate the Wingham FM station was approved by the Commission in English-language FM radio station in Wingham, Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2004-406, 10 September 2004 (Decision 2004-406). In its licence application, Blackburn had indicated that the station would serve Huron County, Southern Bruce County and a small portion of Perth and Wellington Counties, an area essentially matching that defined by BBM Canada as the Wingham Central Market. The Commission noted in its decision that “approval…would provide residents of Wingham and a large surrounding area with access to a third radio service”, to complement those offered by Blackburn’s existing stations CKNX and CKNX-FM Wingham. 3. On 20 December 2004, Blackburn filed the present application to change the station’s technical parameters. In announcing its receipt of that application (Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2005-56, 7 June 2005), the Commission stated that the licensee wished to improve the station’s signal quality to its listeners in Wingham. -

Report on Am Broadcasting Possibilities in the Greater

REPORT ON AM BROADCASTING POSSIBILITIES IN THE GREATER TORONTO AREA Contract U4240-0-0034 Douglas R. Forde FINAL April 17, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2. Acknowledgements 3. Historical Perspective 4. Rules and Agreements 4.1 Rules needing review 5. Overview of all AM Channels 6. Review by Channel Appendix 1. Letter from Gordon Elder on sharing Toronto Island sites Appendix 2. Studies required to assess feasibility of second adjacent channel co-siting 1. Executive Summary This report relates to AM broadcasting aspects of Industry Canada’s response to CRTC Public Notice 2001-10, “Report to the Governor in Council on measures to ensure that the residents of the Greater Toronto Area receive a range of radio services reflective of the diversity of their languages and cultures”. It contains the author’s analysis of the engineering report which the CRTC commissioned from Imagineering Limited on this topic, as well as the results of his own studies. The Imagineering report reviews all current radio broadcasting bands and provides recommendations on each. The following table contains a summary of the possibilities in the AM band identified by Imagineering or the author: Channel Potential Coverage Comments (km in max. dir.) Day Night 790 70 11 Suitable site unlikely to be found. Could operate at lower parameters if colocated with existing station near market. 940 70 2 Requires exception to night-time protection rules. Siting would be difficult. Could operate at lower parameters if colocated with existing station near market.. Mutually exclusive with 950. 950 80 30 Former Barrie station. Needs access to port lands site. -

2019 Huron-Kinloss Community Profile

The Township of Huron-Kinloss Community Profile January 2019 Table of Contents General Information ........................................................................................ 4 Location ...................................................................................................... 4 Transportation Networks .............................................................................. 5 Land Area ................................................................................................... 5 Climate ....................................................................................................... 6 Communities................................................................................................... 7 The Former Huron Township & Kinloss Township .......................................... 7 Ripley ......................................................................................................... 8 Point Clark .................................................................................................. 9 Lucknow ................................................................................................... 10 Human Resources ......................................................................................... 11 Labour Force ................................................................................................ 12 Strategic Plan ............................................................................................... 15 Business Start-Up/Expansion & Labour .......................................................... -

Canada National List

Canada National List Disclosure Media Stock Exchanges & Regulatory Authorities Toronto Stock Exchange News Agency Associated Press Agence France-Presse Canadian Press CanWest Global Communications Corporation Broadcast Networks Broadcast News CanWest Global Communications Corporation CBC Radio Networks CBC Television CTV Television Global Television Network Radio Canada Financial Databases & Websites Advisor for Investors Bloomberg Canada.com Canadian Business Dow Jones Financial Post (part of National Post) Globe & Investor Globe Advisor MSN Canada National Post Reuters Canada StockGroup Stockwatch Thomson Reuters Yahoo! Canada Major Newspaper National Globe & Mail National Post Financial Post Alberta Calgary Herald (Calgary) Calgary Sun (Calgary) Edmonton Journal (Edmonton) Edmonton Sun (Edmonton) British Columbia Vancouver Sun (Vancouver) Vancouver Province (Vancouver) Victoria Times-Colonist (Victoria) Manitoba Winnipeg Free Press (Winnipeg) Winnipeg Sun (Winnipeg) New Brunswick The Daily Gleaner (Fredericton) Newfoundland St. John's Telegram (St. John) Nova Scotia Chronicle Herald (Halifax) Ontario Windsor Star (Windsor) London Free Press (London) Hamilton Spectator (Hamilton) Brantford Expositor (Brantford) Kitchener- WaterlooRecord (Kitchener/Waterloo) St. Catharines Standard (St. Catharines) Toronto Star (Toronto) Toronto Sun (Toronto) Ottawa Sun (Ottawa) Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa) Le Droit – Ottawa (Ottawa) Quebec Les Affairs (Montreal) La Presse (Montreal) Le Devoir (Montreal) The Gazette (Montreal) Le Soleil (Quebec) Le Journal -

Community Profile 2015

COMMUNITY PROFILE 2015 i Grey County © 2015 Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Although all data is believed to be the most accurate and up-to-date, the reader is advised to verify all data before making any decisions based upon the information contained in this document. For further information, please contact: Bryan Plumstead Economic Development & Tourism Manager 102599 Grey Road 18 RR 4 Owen Sound ON N4K 5N6 Phone: (519) 376-3365 ext. 6110 [email protected] Philly Markowitz Economic Development Officer, Local Food 102599 Grey Road 18 RR 4 Owen Sound ON N4K 5N6 Phone: (519) 376-3365 ext. 6125 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 1 22.2 Non-Governmental Organizations 54 2.0 Location 2 22.3 Post-Secondary Education and Training 55 3.0 Climate 3 23.0 Financial Services 57 4.0 Demographics 4 24.0 Real Estate Services 58 4.1 Population Size and Growth 4 25.0 Quality of Life 59 4.2 Age Profile 5 26.0 Housing Characteristics 60 4.3 Language Characteristics 5 27.0 Health, Social and Community Services 61 4.4 Mobility Characteristics 6 28.0 Elementary and Secondary Education 63 5.0 Level of Education 7 29.0 Emergency and Protective Services 64 6.0 Income 8 29.1 Fire Services 64 7.0 Labour Force and Employment 11 29.2 Police Services 65 7.1 Key Indicators 11 29.3 Emergency Services 65 8.0 Labour Force by Occupation 11 30.0 Recreation and Tourism 67 9.0 Labour Force by Industry 13 30.1 Events 67 10.0 Place of Work 15 31.0 Local Media 72 11.0 General Wages by Occupation 17 32.0 Communications -

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION Sept2015 Ontario-Only

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION Sept2015 ROSE highlight = ER Online Ontario-Only (Eng Fre) GREEN highlight = Manual Station Vernacular Lang Type Format City Prov Owner,Firm Main Contact Title Phone Number Email CHLK-FM Lake 88.1 E FM Music; News; Pop Music Perth ONT (Perkin) Brian & Norm Wright Brian Perkin Station Manager +1 (613) 264-8811 [email protected] CKDR-AM 92.7 FM E FM Adult Contemporary Dryden ONT Via FM Acadia Broadcasting 807-223-2355 [email protected] CKDR-FM 92.7 FM E FM Adult Contemporary Dryden ONT CJRN-AM CJRN E AM Music; News Niagara Falls ONT AM 710 Radio Inc. Liam Myers Program Director +1 (905) 356-6710 Ext. 231 [email protected] CHAM-AM 820 CHAM E AM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; [email protected] Music; News; Sports [email protected], CKLH Rep: [email protected] Hamilton ONT Drew Keith Program Director +1 (905) 574-1150 Ext. 421 CKLH-FM 102.9 K-Lite FM E FM Music; News [email protected] CHRE Rep: CKOC-AM Oldies 1150 AM Music; News; Oldies [email protected] CIQM-FM 97-5 London's EZ Rock E FM Music; News; Pop Music CJBK-AM News Talk 1290 CJBK E AM News; Sports London ONT Astral Media Al Smith Program Director +1 (519) 686-6397 [email protected] CKSL-AM Funny 1410 E AM Music; News; Oldies CJBX-FM News Talk 1290 CJBK E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; London ONT Astral Media Chris Harding Music +1 (519) 691-2403 [email protected] Music; News CJOT-FM Boom 99.7 E FM Music; News; Rock Music Ottawa ONT Astral Media Sarah Cummings Program Director +1 (613) 225-1069 Ext. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-123

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-123 PDF version Route reference: 2011-427 Additional references: 2011-427-1, 2011-427-2 and 2011-427-3 Ottawa, 29 February 2012 Various applicants Shelburne and Collingwood, Ontario Public hearing in the National Capital Region and in Blue Mountains, Ontario 19 September and 21 November 2011 Licensing of new radio stations to serve Shelburne and Collingwood, Ontario The Commission approves an application by Bayshore Broadcasting Corporation for a broadcasting licence to operate a new FM radio station to serve Shelburne. The Commission approves in part an application by MZ Media Inc. (MZ Media) for a broadcasting licence to operate a new specialty FM radio station to serve Collingwood. Within 90 days of the date of this decision, the applicant must submit an amendment to the application proposing the use of an FM frequency other than 104.9 MHz (channel 285B) that is acceptable to both the Commission and the Department of Industry. The Commission also approves a request by MZ Media to grant its new station an exception to the Commission’s policy on local programming as it relates to soliciting or accepting local advertising. The Commission denies the remaining applications for broadcasting licences for radio stations to serve Shelburne and Collingwood. Introduction 1. At a public hearing commencing 19 September 2011 in the National Capital Region, the Commission considered four applications for new radio programming undertakings to serve Shelburne and Collingwood, Ontario. The applicants were as follows: Shelburne radio market • Frank Torres, on behalf of a corporation to be incorporated (Torres) • Bayshore Broadcasting Corporation (Bayshore) Collingwood radio market • Evanov Communications Inc.