The Separation of Music and Dance in Translocal Elina Djebbari Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond If you walk on and on, you get to your destination. If you question much, you get your information. If you do not sleep and idle, you preserve your life! (Maung Htin Aung 1959:87) So go the three lines of wisdom offered to the lazy student Maung Pauk Khaing in the well- known eponymous folk tale. A group of impoverished village youngsters, led by their teacher Daw Khin Thida, adapted the tale in 2007 in their first attempt to perform a play. From a well-to-do family that does not understand her philanthropic impulses, Khin Thida, an English teacher by profession, works at her free school in Insein, a suburb of Yangon (Rangoon) infamous for its prison. The shy students practiced first in Burmese for their village audience, and then in English for some foreign donors who were coming to visit the school. Khin Thida has also bought land in Bagan (Pagan) and is building a culture center there, hoping to attract the street children who currently pander to tourists at the site’s immense network of temples. TDR: The Drama Review 53:1 (T201) Spring 2009. ©2009 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram.2009.53.1.93 by guest on 02 October 2021 I first met Khin Thida in 2005 at NICA (Networking and Initiatives for Culture and the Arts), an independent nonprofit arts center founded in 2003 and run by Singaporean/Malaysian artists Jay Koh and Chu Yuan. -

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

Preparing Musicians Making New Sound Worlds

PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Compiled by Orlando Musumeci PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Proceedings of the SEMINAR of the COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya – Barcelona – SPAIN 5-9 JULY 2004 Compiled by Orlando Musumeci Published by the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya Catalan texts translated by Mariam Chaib Babou (except for Rosset i Llobet) Spanish texts translated by Orlando Musumeci (except for Estrada, Mauleón and Rosset i Llobet) Copyright © ISME. All rights reserved. Requests for reprints should be sent to: International Society for Music Education ISME International Office P.O. Box 909 Nedlands 6909, WA, Australia T ++61-(0)8-9386 2654 / F ++61-(0)8-9386-2658 [email protected] ISBN: 0-9752063-2-X ISME COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN DIANA BLOM [email protected] University of Western Sydney – AUSTRALIA PHILEMON MANATSA [email protected] Morgan Zintec – ZIMBABWE ORLANDO MUSUMECI (Chair) [email protected] Institute of Education – University of London – UK Universidad de Quilmes – Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conservatorio Alberto Ginastera – ARGENTINA INOK PAEK [email protected] University of Sheffield – UK VIGGO PETTERSEN [email protected] Stavanger University College – NORWAY SUSAN WHARTON CONKLING [email protected] Eastman School of Music – USA GRAHAM BARTLE (Special Advisor) [email protected] -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

An Analysis of the Religious Belief Characteristics of Southeast Asian Dance

2020 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Sciences & Humanities (SOSHU 2020) An Analysis of the Religious Belief Characteristics of Southeast Asian Dance Feirui Li Guangxi University For Nationalities, Guangxi, Nanning, 530006, China Keywords: Southeast asian dance, Religious beliefs, Thailand Abstract: The dances in Southeast Asia are colorful and can be divided into four major dance systems: Buddhism, Puppet, Hinduism and Islam. The four major dance systems are influenced by India's two epics. In some Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand and Vietnam, their religious culture is closely linked to dance arts. Strong religious culture permeates dance music, style and dance vocabulary. Based on the analysis of Southeast Asian dance art, this paper takes Thai dance art as an example to further elaborate its religious and cultural charm. 1. Introduction Engels said that religion, like philosophy, is a “higher, i.e. more far from the material economic foundation of ideology” [1]. However, as an ideology, it not only experienced the process of development and processing, but also developed independently according to its own laws. Religious culture and dance culture. Asean art, as a new breakthrough in Chinese art research, is very research-oriented [2]. Southeast Asia is made up of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia and other countries. Due to geographical and religious reasons, Southeast Asian countries represented by Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar live alone in dance culture and are relatively developed [3]. Dances in Southeast Asia have strong religious color of Buddhism and Hinduism. As a result, the dance branches in Southeast Asia present four major dance departments, namely puppet dance department, Hindu dance department, Buddhist dance department and Islamic dance department. -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Rebranding Initiative

REBRANDING INITIATIVE Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. History and Summary of Issues. 2. Review of Strengths and Weaknesses. 3. Suggested Actions Organized in the Following Categories: a. Board Structure b. Administrative Structure c. Financial d. Choir Structure and Performances e. Marketing 4. Current Mission and Vision Statements Page 2 HISTORY AND SUMMARY OF ISSUES The San Antonio Choral Society began in 1964. It’s original purpose was to provide a community based choir that would be large enough to sing master works and more difficult works than most church choirs could perform. The choir drew members from all over San Antonio (mostly from church choirs) and was an instant success. SACS continued in that mode until the 1990’s when the repertoire was expanded to include more popular music. In 1996, Broadway musicals were added for a “Pops” concert. The choir continued to be managed by a group of charter members until 2013 when a large number of charter members retired from the choir. At that time Jennifer Seighman was hired to be the artistic director for the choir. Jennifer began to raise the standard in terms of music quality, performance arrangement, singer’s skills and music education. Everyone enjoyed the new challenge. In addition, in 2014 the choir was the beneficiary of sizable funds from the estate of a deceased member that continued through 2016. Those funds have now ceased leaving the choir in a quandary as to how to deal with increased costs of operations and no clearly defined revenue source. The loss of funds has caused the officers to reassess our current situation and try to project what direction is needed for the future. -

Connecting Through Dance

Connecting Through Dance: The Multiplicity of Meanings of Kurdish Folk Dances in Turkey Mona Maria Nyberg Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the M.A. degree Department of Social Anthropology, University of Bergen Spring 2012 The front page photograph is taken by Mona Maria Nyberg at a Kurdish wedding celebration. The women who are dancing in the picture are not informants. II Acknowledgements While studying for an exam during my time as a bachelor student, I read a work by Professor Bruce Kapferer which made me reconsider my decision of not applying for the master program; I could write about dance, I realized. And now I have! The process has been challenging and intense, but well worth it. Throughout this journey I have been anything but alone on this, and the list of persons who have contributed is too long to mention. First of all I need to thank my informants. Without you this thesis could not have been written. Thank you for your help and generosity! Especially I want to thank everyone at the culture centers for allowing me do fieldwork and participate in activities. My inmost gratitude goes to two of my informants, whose names I cannot write out of reasons of anonymity - but you know who you are. I want to thank you for allowing me into your lives and making me part of your family. You have contributing to my fieldwork by helping me in in innumerous ways, being my translators – both in terms of language and culture. You have become two of my closest friends. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

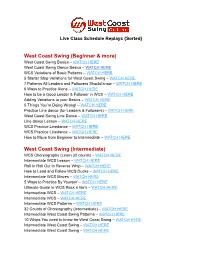

West Coast Swing (Beginner & More)

Live Class Schedule Replays {Sorted} West Coast Swing (Beginner & more) West Coast Swing Basics – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Dance Basics – W ATCH HERE WCS Variations of Basic Patterns – W ATCH HERE 5 Starter Step Variations for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE 7 Patterns All Leaders and Followers Should know – W ATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice Alone – WATCH HERE How to be a Good Leader & Follower in WCS – WATCH HERE Adding Variations to your Basics – W ATCH HERE 5 Things You’re Doing Wrong! – WATCH HERE Practice Line dance (for Leaders & Followers) – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Line Dance – WATCH HERE Line dance Lesson – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE How to Move from Beginner to Intermediate – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing (Intermediate) WCS Choreography (Learn 32 counts) – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Lesson – WATCH HERE Roll In Roll Out to Reverse Whip – WATCH HERE How to Lead and Follow WCS Ducks – W ATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Moves – WATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice By Yourself – WATCH HERE Ultimate Guide to WCS Rock n Go’s – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Patterns – WATCH HERE 32 Counts of Choreography (Intermediate) – W ATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing Patterns – WATCH HERE 10 Whips You need to know for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing ( Advanced) Advanced WCS Moves – WATCH HERE